THE HIGHWAYMEN TRANSCRIPT

Episode 1: Democracy, we’ll miss it when its gone

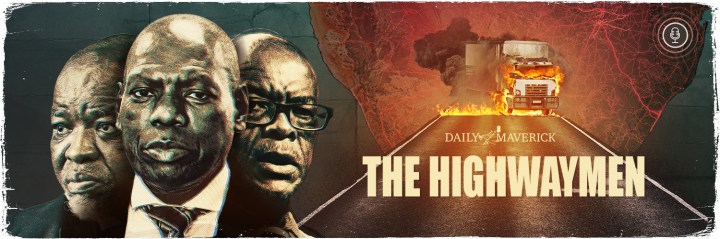

In December 2022, the 55th – and possibly last – elective conference of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress will take place against a backdrop of socio-political chaos. In the limited audio documentary series, The Highwaymen, investigative journalists Richard Poplak and Diana Neille take a road trip across South Africa in search of answers to how the country got to this breaking point, and how the lives and careers of three senior ANC figures – Ace Magashule, Gwede Mantashe and Dr Zweli Mkhize – may be representative of the rise and stumble of our once vaunted democratic project and, by extension, liberal democracies everywhere.

In episode one, Poplak and Neille meet with two self-described community activists in Durban, who stepped into the void created by a government that couldn’t cope, during the eight days of riots that followed former president Jacob Zuma’s incarceration in July, 2021. Then, they make their way up to the outskirts of Pietermaritzburg, to the birthplace of a presidential hopeful whose story is representative of the devolution of South Africa’s ruling party, the African National Congress.

Below is the full transcript of episode one, with links to the clips, documents and articles gathered and referenced in the reporting and research for it.

***

Emeritus Justice Sisi Khampepe: It is declared that Mr Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma is guilty of the crime of contempt of court…

NEWS CLIP: South Africa’s former president, Jacob Zuma, has been sentenced to 15 months in prison…

NEWS CLIP: The country waits to see if Jacob Zuma will hand himself over to police tomorrow… There’s mobilisation by various supporters of the former president in Nkandla…

NEWS CLIP: Just minutes before the midnight deadline, Zuma left his home in a convoy of vehicles… Zuma’s imprisonment comes after a week of rising tension over his sentence.

NEWS CLIP: …The most strategic trade route, the N3, was blocked and closed… due to the ongoing protests under the hashtag shut down KZN… I can tell you there is a sense of fear, confusion and uncertainty…

NEWS CLIP: It looks like the convoy… Yes! It has those presidential coat of arms on the side… Confirming that… The former president Jacob Zuma… is one of the inmates that will be sleeping here this morning.

NEWS CLIP: In the past days, looting has spread from stores to factories and warehouses, ransacking and rioting in South Africa’s worst violence since apartheid.

NEWS CLIP: All the doors are open… There’s absolute lawlessness.

NEWS CLIP: Protests started with the jailing of… Jacob Zuma… His supporters see his treatment as a symbol of the current government’s repression.

Richard Poplak: Over the course of eight days in July, 2021, South Africa had a nervous breakdown.

The good news is that we joined the very short list of countries to send a corrupt former president to jail, even if his term was cut short by an innovation South Africa has perfected – medical parole.

The bad news is that no one seemed to anticipate the blowback. In the wake of Zuma’s jailing, 354 people died in the looting and destruction, and $3.5 billion – R50 billion – was lost from the economy. When those eight days were over, chunks of the country lay in ruins.

Visitors to South Africa, many of whom haven’t checked in since Nelson Mandela became president in 1994, now ask: How did the country get from this:

Former President Nelson Mandela: Out of the experience of an extraordinary human disaster that lasted too long must be born a society of which all humanity will be proud.

Richard Poplak: To this?

Former President Thabo Mbeki: You remember what happened in Tunisia… When that Arab Spring started? It was… A little spark… One of these days it’s going to happen to us. One day it’s going to explode.

Richard Poplak: That was a comment by Thabo Mbeki, Mandela’s successor, made earlier this year. And we have news for him: South Africa is exploding.

I’m Richard Poplak, and I’m reporting this story with my colleague, Diana Neille.

Diana Neille: We’re investigative journalists and filmmakers, who spend our days reading, writing about and investigating corporate and political corruption.

In other words, we’re democracy’s proctologists. And like most people in our profession, we work without gloves.

We started reporting together in 2015, on a story about labour malpractice at Coca-Cola. Then we made a film about the world’s most toxic public relations company, Bell Pottinger. Back in those halcyon days, we thought we could at least see corruption’s contours — where it began, and where it ended.

Seven years later, it feels like we’re drowning in an ocean of toxic sludge. Across the so-called free world, politics now belongs to a cabal of lurching savages. From the floor of the United States Congress to the presidential palaces of SouthEast Asia, corruption is such a common feature of global politics today, that it’s become predictable. Entrenched.

Our systems don’t just condone that corruption. They seem to create it. Manufacture it, on an industrial scale.

And the outcome is almost always telegenic mayhem.

Former Us President Donald Trump: We’re gonna walk down to the Capitol… You’ll never take back our country with weakness.

NEWS CLIP: The government did this to us! We were normal, good, law-abiding citizens!

NEWS CLIP: What’s happening in Sri Lanka is much more than an economic crisis. It is a humanitarian crisis. The question is, how did it happen?

NEWS CLIP: Discontent is boiling over in Colombia. At least 24 people are dead after… days of protest and a brutal crackdown.

NEWS CLIP: The City of Light dissolved into a battle ground, as police and protestors crashed over proposed Covid-19 restrictions. Rallies were held across Paris on Saturday.

NEWS CLIP: Hundreds of thousands of farmers marched into Delhi, from neighbouring states.

At the heart of this protest: New agricultural laws passed by the government.

Diana Neille: These violent scenes of unrest all took place over the course of 2021 alone.

According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, there were over 76 major popular uprisings on the planet last year.

The American research organisation Freedom House reported in 2022 that global freedom has declined for 16 consecutive years, as attacks on liberal democracy ramp up. The organisation’s Freedom in the World Report states that the global order is nearing a tipping point, with three out of four people living in a state of democratic breakdown, oppression or outright authoritarianism.

In other words, liberal democracy is having a bad century.

Richard Poplak: In the brutal hangover following its own brief moment of electoral ecstasy in 1994, South Africa has been dismissed as just another developing world backwater, backsliding into the cradle of humankind, a vicious Hobbesian cage match for the last kudu on the highveld. But, it’s worth reminding ourselves that South Africa is a working example of a liberal democracy, with a progressive constitution, governed for the past 28 years by the African National Congress, a century-old organisation with a broad ideological range and a long history of democratic engagement.

The ANC faces off against a free press, and well-financed opposition parties that contest free elections, under the watchful eye of a functioning judicial system and a robust civil society.

Is that democracy? Well, it depends on who you ask.

And anyway, to quote the political analyst Astra Taylor, democracy may not exist, but we’ll miss it when it’s gone.

It comes down to this: if democracy – whatever that word means – can flame out in South Africa, it can flame out anywhere. And it has, and it is.

With all this in mind, we decided to go on a road trip through post-meltdown South Africa, and see if, in the wreckage, we couldn’t pinpoint the causes of our own insanity. And, in the process, discover clues for why the entire world seems to be losing its collective mind.

We chose to focus on three figures, who we feel represent the various ways in which democracies can absolutely annihilate themselves. They are Ace Magashule, Gwede Mantashe, and Zweli Mkhize. We’ve chased their lives and legacies around the bottom of Africa.

We call them and their ilk, The Highwaymen.

So I guess this is a true crime podcast. It’s the story about the murder of a country. And yours might be next.

Diana Neille: Trouble often begins in the coastal province of KwaZulu- Natal, South Africa’s ungovernable diva. After all, this is where the July riots kicked off. And so begins the world’s most dystopian road trip.

Among other things—polluted beaches, sharks full of plastic, apocalyptic truck crashes on decaying roads— the province is the seat of power of our former president, Jacob Zuma and the syndicates that swirl around him.

These various groups are, of course, aware that in the battle for control of the ANC, the party will go to its national elective congress at the end of 2022. There, it will pick its leadership in advance of national elections in 2024.

And while KZN forms a large part of the political mythology of the ANC, and of South Africa more generally – the media hasn’t always done a great job of placing it in a wider context.

The province is, and has for the duration of democracy, served as a generator of chaos — chaos that is both politically and economically fungible.

Our first stop is the neighbourhood of Morningside in Durban. Amid dense subtropical foliage and the battle cry of hadeda versus seagull, we make our way into a compound surrounded by the high walls and electric fences of middle class South Africa. We’re here to meet two self-described community activists, who run a growing private security network. They’ve kitted out a home office with a small control centre that monitors the city 24 hours a day – a surveillance hub that never stops watching or listening.

Mohammed Ismail: My name is Mohammed Ismail, I am a member of the community police forum. I would like to think of myself as a community activist also.

Zain Soosiwala: My name is Zain Soosiwala… All we are is a bunch of guys who came together with common purpose, and that is to keep our areas safe. [We] formulated something called eThekwini Secure, which has now about 28 different subsidiaries.

Mohammed Ismail: A community police forum is… a consultative body made up of members of the community, who sit alongside the… Formalised police… You know, it’s a legislative body, and you’ve got to work within the ambit of the law.

Zain Soosiwala: We all at some point have been disenfranchised and have lost faith in the structures that are out there… We could have either gone off one of two directions: We could have become vigilantes and taken onto the road, and done our own thing, but we didn’t want to be that way… Instead of working against the flow of things, we decided to become force multipliers within the structures that are currently there… [And] we’ve become sort of the go-to guys in the area… The communities look to us for support, guidance and then we, in turn, put our heads together and then we find alternate solutions.

Richard Poplak: When the uprisings of last year exploded, crime intelligence, along with state security agencies, were caught with their pants around their ankles. This was strange, given the levels of paranoia the governing ANC has become known for. Every cadre is terrified of the cadre next door. But clearly, not terrified enough.

According to the Report of the Expert Panel into the July 2021 Civil Unrest, there was overwhelming evidence that the authorities had received information showing trouble brewing well ahead of time. Aside from formal intelligence briefings, which repeatedly identified instigators and their possible intentions, there were countless tweets, TikToks and Whatsapps, and even phone calls to high-level officials from the public.

The only thing missing was a six-part Netflix series called Your Country’s About to be Set On Fire.

Soosiwala and Ismail, among many others, set up neighbourhood barricades and patrols to stop looting in their communities, and to ensure that properties and people were kept safe.

Zain Soosiwala: The fear at the time was absolutely palpable… [There’s] this app that converts your phone into a two-way radio… That Zello channel went from five to six hundred users on a daily basis, to 20,000 people during the civil unrest. That’s within 48 hours.

And I went on, and I said, any able-bodied men, women… Anyone who wants to assist, take to the defences of your community. We are alone, no one is going to come to our defence right now. Our law enforcement… Are calling upon us for protection, so you need to protect your own.

We slept in our cars with bullet proof vests on. We were running the barricades… there was no oversight from anybody else. We needed to ensure that all our areas were on lockdown.

We saw the coordinated – and I’m using this word, coordinated – attack on the Macro area… We saw how the gates were dismantled…These guys came in with long guns, they reversed their trucks into the entrances at Macro, they took whatever consumer electronics, goods, they loaded them in. And then, when they left, the taxis all lined up…

And the settlements started coming towards us… and at that point, thousands of people… Marauding, running at breakneck speeds to get in there.

There was no stopping those crowds. At some point, they lost control of it. At some point it became a free-for-all.

Richard Poplak: Like a scene out of an unpublishable Cormac McCarthy novel, the very real threat of babies starving to death started to present itself.

Zain Soosiwala: After like day three, and all the shops are closed, there’s nothing to be had, basic necessities are now running out, the main thing we needed to do was, now, to protect the food supplies. Whatever we have here. But more importantly… Start bringing in… food, aid, medication, bread, milk – basic supplies.

So 42 trucks had to be brought in from Johannesburg to Durban. We got permission from Disaster Management to go up and to protect this convoy… to bring it back. And then you start to see the effects of what these trucks did to the communities.

We unpacked the trucks… all the lines that were running, wrapping around neighbourhood blocks.

You realise that this incident had an impact on everyone.

It’s actually painful to mention it… It’s still, in some ways, very much fresh.

It’s my personal belief that we’re not out of the civil unrest…And people are still living in this state of anxiety. And I think much of it is because there’s not been an equal reaction from the government. From the powers that be, to ensure that we reach a state of normalcy.

Diana Neille: ‘A state of normalcy.’

Well how’s this for normal?

Well, how’s this for normal? This is an excerpt from the Report of the Expert Panel into the July 2021 Civil Unrest. “The looting, destruction and violence have come and gone, but we found that little has changed in the conditions that led to the unrest, leaving the public worried that there might be similar eruptions of large-scale unrest in future. It’s not if and whether more unrest and violence will occur, but when it will occur.”

This is what ends up happening: a country’s own civilians are providing the basic services of the state for themselves and for each other. Protecting their neighbourhoods, feeding people, providing medicine.

From one perspective, Soosiwala, Ismail and their posse are active and engaged citizens. They’re willing to literally take up arms to protect their community, in the vacuum created by an under-functioning government.

From another perspective, eThekwini Secure functions as just another sub-saharan African paramilitary outfit, a NIMBYist cosplay club with lots of guns.

In this dichotomy, between these two perspectives, lurks what remains of the South African state. It’s a phenomenon public intellectual Songezo Zibi has been studying for a long time. He’s the co-founder of the Rivonia Circle, a social-democratic think-tank that hopes to remedy this mess.

Songezo Zibi: If you understand national security to be the ability of a country to, robustly, look after itself and the interests of its people, that erosion started a long time ago.

Our security agencies are… in the payroll of criminal elements, organised crime.

These criminal elements… are embedded, they’re now one and the same with the ANC. So what you have is a gang war. And that gang war, because it’s in the political sphere, needs mass support. And that’s how you end up with an ‘insurrection’.

Because, let’s be honest, the person who was formerly president of South Africa, was running a criminal enterprise… So you take the mob boss and you put him in jail – what does it say? It says none of the rest of the minions are safe and anybody who’s got anything to fear in terms of criminal charges is going to be very worried.

Richard Poplak: Soosiwala and Ismail were some of the only people standing between that gang war, and their communities.

For us, they reveal the mechanics of how South Africa and other failing developed and developing nations have begun to unravel. We’ve seen this in our reporting, time and time again. Those who can afford to, pay groups like eThekwini Secure to keep themselves, their families and their properties safe. Those who can’t must organise in other ways.

Think about it this way: In South Africa, the official unemployment rate is 34.5%, climbing to a staggering 63.9% for 15 to 24-year-olds. That’s a figure that would be a death sentence in most middle-income countries. But here, the vast and documented inequality has become encased in concrete – part of the architecture of everyday life.

These statistics have become the stuff of economic legend.

Thomas Piketty: Now that we are 25 years after the fall of apartheid, we are all puzzled by the fact that inequality not only is very high in South Africa, but even in some way has been rising.

Richard Poplak: The French economist, Thomas Picketty, has written by far the most influential book of economics in decades, called Capital in the 21st Century. Its central premise is how we’ve entered a new gilded age of extreme inequality, and its first chapter kicks off right here in South Africa, in Marikana – the settlement on the platinum belt where 34 miners were massacred by police in August 2012, during a wildcat strike for better wages.

Just out of interest, the current owner of that mine, Neal Froneman, took home a R300-million or $18-million compensation package last year alone.

The walls and electric fences between rich and poor get higher and the barricades on suburban streets become permanent. Neighbourhoods become enclaves, policed by private militias, monitored by the digital eye.

As far as Ismail is concerned, this is where free-style political improvisation takes shape.

Mohammed Ismail: We become the politicians. We become the police, we become everything, because now we need to bring back the racial harmony, we need to bring back social cohesion, we need to look after those aspects, because … if you just take a drive to Overport and you look at the imbalance of the economy, you’d find people living in dire poverty. And then you get people who are super wealthy, and I mean super wealthy. So your imbalance is right in front of you. And that’s left up to us.

Go back in South Africa’s political history… fighting together as a single community for the freedom of this country, for your rights, for your education, your right to healthcare, your right to anything else, and then the euphoria came about, 1994 elections, 27 April. We attained our freedom, but what freedom did you attain, when you’re sitting in a situation like this, that is politically volatile?

Diana Neille: To find the answer to this question, we need to go back in time, to the beginning. If Soosiwala and Ismail are the present tense, the point at which democracy in the second decade of the 21st century has landed us, what got us here in the first place?

How do we make sense of the journey we’ve taken, as a country as complex as this one is?

As we’ve said, we believe that South Africa is emblematic of the global rise and stumble of liberal democracy in its various incarnations. And in our work studying democratic flameouts, we’ve come up with a seven-point breakdown to diagnose this progression. In the South African context, because of the specifics of our history, this seven-point breakdown has happened within and around the ANC, which has, by and large, been the only game in town politics-wise.

It goes like this: Ideological contestation leads to divisions, which result in factions, which create corruption – or, rather, elite capture – which leads to state capture, which atomises into organised crime, which results in all-out gang warfare.

In order to illustrate these points, we want to start with one of the Dons of KZN – one of the men who have helped mould this province into a cabal of weaponised zombies, chowing the last remaining state resources to buy ugly cars and badly built mansions.

And we’ll begin his story during his brief moment of greatness.

NEWS CLIP: …Ahead of the impending lockdown, possibly the person sleeping the least during this unprecedented time is Health Minister Dr Zweli Mkhize.

Minster, thanks so much for coming through…

Dr Zweli Mkhize: Thank you, good morning to you… We are expecting that there’s going to be quite an increase in the numbers of cases. And we also expect that a lot of work has to be done by South Africans to contain these infections.

Richard Poplak: As Health Minister at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr Zweli Mkhize took South Africa in his capable physician’s hands, mopped our fevered brows, and rocked us gently into our lockdown slumber.

When we woke up, we found out that he had stolen R150 million.

NEWS CLIP: Top story this evening of course, the health minister is on special leave. The presidency says this is to allow the health minister to attend to the allegations regarding the contract between the health department and service provider, Digital Vibes.

Richard Poplak: From Covid hero to Covid zero in a matter of weeks – that’s what most South Africans know about Mkhize. In June 2021, a company called Digital Vibes, which sounds like a Kyrgyzstan dating site from the late ‘90s, was embroiled in a R150 million pandemic funds scam. After comprehensive sleuthing by Daily Maverick journalist Pieter-Louis Myburgh, evidence emerged that Mkhize, his cronies and his family, ran Digital Vibes as a personal cash machine.

This meant that the Good Doctor was implicated in a pandemic of thievery which, it turns out, was happening in democracies everywhere. Long Covid’s list of symptoms should include the significant costs imposed by white collar pandemic corruption.

In other words, Mkhize found himself in good company.

Before the Digital Vibes scandal, he enjoyed a long career as a member of the country’s ruling elite. He’s a former peace broker, a former premier, a former presidential hopeful, and a man around whom myriad accusations circulate. Indeed, Mkhize is campaigning to become president of the ANC again, at its 55th elective conference in December 2022, even as law enforcement agencies close in on him. And he’s one of the creators of the modern KZN imaginarium.

Soosiwala and Ismail live in the Mkhize Multiverse where, of the 418 political assassinations recorded nationwide between 2000 and 2021, 118 took place right here in KZN.

NEWS CLIP: Notorious for hit men that will pull the trigger for a price, KwaZulu Natal has seen at least 27 Izinduna assassinated, with several others narrowly escaping death in the last two years. The brutality is strongly reminiscent of the political violence of the 1980s and the ‘90s, when deep-seated political rivalries saw a battle for supremacy.

NEWS CLIP: The task team dealing with political killings in KwaZulu Natal has 32 more cases, since June 2021. Most of these have either come before or after local government elections.

News Reader: According to data collected by the Global Initiative on Transnational Organised Crime, there’s an increase in the number of assassinations in the country since 2015. Of the political hits recorded across the country between the years 2000 and 2021, 213 took place in the last seven years, and of that number, 118 were in KwaZulu Natal.

Diana Neille: Remember we outlined the seven-point progression of how political institutions tend to devolve over time?

KZN, and South Africa at large, are much easier to understand when placed in the context of our second point on that continuum – how ideological contestation gives way to divisions, which in turn calcifies into factions and the rent-seeking of a kleptocratic elite.

Mkhize has played a part in every one of those steps. And his loyalty to the party has never wavered.

Dr Zweli Mkhize: The resolution to strengthen the structures of the ANC and root out bad elements and bad tendencies is highly supported… We want to say, as the province of KwaZulu Natal, all the ANC needs to do is to call on us. We shall be there.

Diana Neille: Well, Soosiwala and Ismail would likely dispute that fact.

Zain Soosiwala: The people just needed a voice of reason, and it was not coming from anyone at that point. No ward councillor stepped up at that point, no politician came forward, no law enforcement was here. Communities were left on their own.

I still don’t have full faith that anyone will take our place. And I’m quite happy to relinquish the position that I have right now, and hand it over to someone, anyone who is willing to step up and say, if this were to happen again, we will take over, we will be that bastion that will stand up, and we will put out this clarion call to tell people, be calm and we will take over, we will run the city as though it’s supposed to, and we will prevent any civil unrest from happening again, but the reality is, we have nothing.

Richard Poplak: That’s the terrifying, hard-to-hear truth. But the reason we’re on this journey is to figure out if there are ways to reverse this terrible trajectory.

First, though, we have to understand it.

As we’ll soon find out, when the ANC began oxidising in the fresh air of democracy, the corrosion was almost immediate. As the battle against apartheid became a memory, the new dispensation set the rules for the divisions Soosiwala, Ismail and their community are grappling with today.

Mohammed Ismail: I remember those days, as vividly as if it was yesterday. We fought for the cause, but what cause are we fighting now? We’re fighting against the political party that was supposed to have brought you those freedoms, but put you back in chains… because of their fragmentation, because of their fracturing. How do we repair that?

Richard Poplak: How, indeed? Anyway, we can tell you what Zweli Mkhize’s going to do. He’s giving it one more go.

Dr Zweli Mkhize: My name is Zweli Mkhize. My branch has joined numerous other branches in nominating me to contest the position of the ANC president at our upcoming 55th National Conference.

Richard Poplak: So Mkhize’s running, and we’re running after him. All the way through the province he’s helped ruin. DM

For more visit The Highwaymen

Fact check, additional research and editorial oversight by Sasha Wales-Smith.

The Highwaymen was produced with support from the Friedrich Naumann Foundation (the content may not necessarily reflect the Foundation’s views or opinions).

We are watching the US mid – term elections with the return of Trumpism looming very large over the elections. This is against the background of the rise of the right in Europe and the return of the corruption charged Netanyahu. One is raising these issues as one is looking at our own situation that the writers are reflecting on. One is asking himself a question of what a rational person is and why would people support people who have stolen public resources and is it rational to say who is not a thief? You would expect a party led by a thieves to lose elections or those who are not involved in criminal activities to show contrition. No, they are just arrogant and do not care and fighting corruption is just speak for them. I listen to two Provincial leaders when they speak within the ANC, Zamani Saul and Mdumiseni Ntuli. Zamani Saul says as soon as those who face criminal charges are brought into power, they will rubbish the Zondo Commission and we must forget accountability on state capture and corruption.

He is very genuine when he speaks. You then have the ANCYL Task Team that seems not to care a hoot about corruption but on how fast they can get to the feeding trough themselves to get their own Gucci. You then wonder whether you are normal for wanting those who have committed crimes against the state and the people of South Africa to account when the majority sees nothing wrong. But there is hope as the tide is turning against corruption but needs support.