LEGAL GIANT OP-ED

Remembering Gerald Friedman – a long life of decisiveness, principle and example

From a grindingly hard childhood, Gerald Friedman became a giant of the legal fraternity, with a lifetime reputation for exactitude, soundness and unremitting diligence. He became known to those who appeared before him as a judge’s judge. No sense of himself, but a sense of the court: its dignity, its efficiency, its fairness. In private he could be irreverent and, unbending, very funny.

Should anyone have accepted judicial appointment under apartheid? Or if they had already done so, should they have resigned as judges when some new piece of repression was devised which they were bound by oath to apply? If not, what could and should they have done? These were hard questions in the 1970s and 1980s.

One who faced and answered them was Gerald Friedman, advocate, judge, judge of appeal and judge president. He was appointed a judge at the time of a welter of bans on media and organisations in 1977, and just a month before the death of Steve Biko. He served until 1998. Friedman answered the hard questions both explicitly and through a long life.

Friedman died at his home on the Kom in the South Peninsula earlier this week. Two days later he would have turned 95. It was, he had said a week or two earlier, enough. So he declined food and drink and slipped away. He had lived a long life of decisiveness, principle and example: “Nothing became it so much as the leaving it.”

His generation has easily attracted the modern inference of advantage: after all, he was white, Jewish, degreed, from a good university. In fact, his upbringing was grindingly hard, in every way. His paternal grandfather, from Russia, was a smous, living on the fringe of the ostrich trade. Friedman’s father had a shop at the Robertson station. Later he took over the Knysna Hotel: a few shabby rooms and a bar. His mother ran the bar. His father died when Gerald was three. His mother never forgave him for leaving them in dire need. Friedman was sent to school in George, lodging with some other boys in a boarding house, harsh and dismal. When he was in matric his mother moved to Cape Town, for medical treatment. She had to sell the hotel to raise money for his education. Mother and son lived in a one-room flat above the Mowbray station until his marriage, 10 years later.

The young Gerald thought of medicine. But it was not helpful that he always fainted at the sight of blood. He liked debating, much admiring a local attorney in George. (He was fortunately not dissuaded from choosing law when his role model was both struck off and sent to prison).

Entering UCT at 16 in February 1945 – he was set on joining the war, but was too young – by 21 he had his BA and LLB. He joined the Cape Bar in 1950. Those were slow years in legal practice, but soon Friedman was a rising junior, with his lifetime reputation for exactitude, soundness and unremitting diligence. He took Silk in 1970, was elected leader of the Cape Bar, serving on the General Council of the Bar. His practice had a wide range: it straddled commercial law in all its forms, shipping, tax and the burgeoning field of administrative law. He shared a suite with another rising junior, Johan van Zijl Steyn, who later emigrated and rose to the House of Lords. Bar back-biters said the two were touts: after all, they had a carpet, and a typist, instead of hand-writing their opinions and pleadings. Steyn and Friedman remained lifelong friends, as Friedman did with a second brilliant emigré to the UK, Lord Hoffmann and his wife Gillian, who made sure to visit him every year.

As a Bar leader Friedman authored critical public dissections of the welter of repressive measures in the 1970s. Of course that was hardly, he said drily, career-advancing. But as he later wrote, it was anyway known that he (like a number of other future appointees to the Bench) had no political allegiance to the then ruling party. Already as a junior at the Bar he had been pointedly asked, in the corridor by a judge, whether he had thought through the consequences for himself of appearing in “political” matters. He had. Life long, he had no time for a fudging of the “cab-rank” rule – the Bar ethic that your client’s opinions are not yours, and conversely yours are not theirs. Just do your job, he said – without favour to them or fear for anyone else. That included in his case acting for the notorious scissors-murderer, Marlene Lehnberg. She was sentenced to death. Friedman’s success in persuading the trial judge after sentence to admit new evidence undoubtedly helped save her life on appeal. That was the beginning of a long friendship with Ismail Mahomed, who appeared for Lehnberg’s co-accused, Marthinus Choegoe, and went on to become chief justice.

His manner was austere, firm, but listening. Woe betide the unprepared or the foolish.

And as to what your job is at the Bar, he said no one put it better than Dr Johnson: it is to give all your legal knowledge and professional skill to say for your client anything they could reasonably say for themselves. As he watched in his last years televised hearings involving surrealist rhetoricians, he emphasised: reasonably.

The high regard in which Friedman was held as a young judge appears from the difficult case allocations he received from the three judges president under whom he served. He was in the heaviest cases, whether alone or on Full Benches. He became known to those who appeared before him as a judge’s judge. No sense of himself (judgeitis, as the affliction is known), but a sense of the court: its dignity, its efficiency, its fairness. His manner was austere, firm, but listening. Woe betide the unprepared or the foolish. His face, usually set in a frown of concentration, could set in a hard and wintry look.

But then he again bit the hand that fed him. A Full Bench was convened to hear an urgent application on behalf of (he was in detention, and incommunicado) a member of the Bar, Dullah Omar. Two of the three judges, including Judge President Munnik, ruled that Omar had no right to be heard before he was indefinitely detained. Friedman J delivered a meticulously reasoned and researched dissent. It has, in time, become a locus classicus.

Rights as facts

From biting the hand he turned to biting the crocodile itself. The town in which Friedman had spent his most miserable years had become PW Botha’s constituency, cosseted and controlled by the now-president. George Municipality set about levelling shacks in Lawaaikamp, its blikkiesdorp, with no regard for procedural or property rights. In a clinical dissection of fact and law – no doubt a vivisection for its lawyers – Friedman J stopped the Council in its tracks. As in Omar, not a single rhetorical flourish. He dealt with rights, as far as they ran, as matters of fact. For him adjectives were distracting, even unseemly. In retirement he winced at florid Constitutional Court judgments.

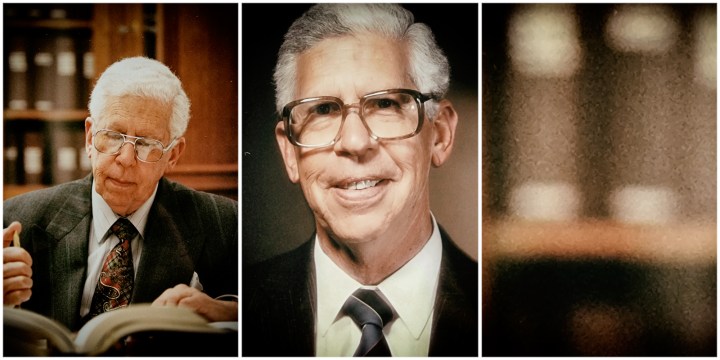

Gerald Friedman and Jeremy Gauntlett at the launch of their book, ‘Bar, Bench & Bullshifters’, at the Book Lounge in Cape Town in 2013. (Photo: Benny Gool)

Many thought that Friedman’s card was now marked: he would see out his time as a highly regarded Cape High Court judge. But 1989 saw a new Chief Justice. Michael (Mick) Corbett had once caused consternation to the government by delivering a ground-breaking paper at the University of Cape Town on the daring topic of human rights in South Africa. Corbett moved with deliberate speed. His own tenure should have commenced in 1986, but he was mistrusted by the government, and so the term of Rabie CJ had been extended for another three years. Corbett ensured that acting, then permanent, appointments came the way of the Corbett Kindergarten, as some called them: a group of younger judges known as brilliant lawyers, and (Corbett himself having been a trailblazer) for an ability to apply common law rights in the narrowest gaps left between the hard stones of statutes. Friedman was the first, then Goldstone, Nienaber, Goldstone, Kriegler, Howie, Harms. Administrative and labour law in particular were remodelled.

But now the Cape judge presidency fell open. The decade-long tenure of Munnik JP had ended. Friedman’s wife of more than 50 years, Yvonne, was an artist and an actress. Her flair and creativity (introducing him to theatre, ballet and symphony concerts) had not thrived in Bloemfontein, and they decided to take the opportunity to return home.

For eight years Friedman led the Cape court, in every sense. Colleagues and practitioners alike knew they had a great judge president. His leadership skills were evident. Few judges are both very good lawyers and administrators. He marvelled in later years to read about judges not delivering judgments. His comment was that that was the judge president’s fault. He would himself “go along the passage” for “a quiet word”. For two recidivists (unable, he said, even to remember their delinquencies) he had a gulag-like cure: he would “put them in crime” (where they couldn’t reserve judgments) for as long as it took to catch up.

He himself took the hardest and worst cases: the latter being cases bound to attract opprobrium for the judge, whatever they did. One example was the trial of Juan-Pierre Havenga and Antonie Wessels, who had sadistically brutalised and murdered a lone hiker in the Outeniqua Forest. Havenga was under 18 at the time, so Friedman imposed a long jail sentence. But Wessels he sentenced to death. Characteristically, he saw it as his duty, and he did not flinch from it.

Another was the mob murder of a young Fulbright scholar, Amy Biehl, a volunteer worker in South Africa. He found the killing to have been “cold-blooded and brutal… on a defenceless young girl… who had already sustained a serious injury to her head from which she was bleeding profusely”. Friedman said he had considered the death penalty. But because there was a chance that the three young killers could be rehabilitated “despite the fact they have shown no remorse”, he imposed sentences of 18 years’ imprisonment, not death. There was an outcry. In fact, he was prescient: they were amnestied, went on to live useful lives, acknowledging the wickedness of what had happened, even working for the Amy Biehl Foundation, established by the victim’s grieving parents. This year they met with her mother to commemorate Amy’s death 30 years ago. Both cases would have imposed, he felt, unfair burdens on a junior judge. Both decisions took judicial courage.

Friedman took pride in the court he ran, and which initially with Dullah Omar, now minister of justice, and thereafter the Judicial Service Commission he helped assemble around him. He was responsible for recruiting the first Cape female senior advocate (Jeanette Traverso) as a judge, the first academic lawyer (Dennis Davis) and the first Cape judges of colour. He mentored them: always available, as Davis has recalled, to give advice, to edit a draft judgment, to steer them off rocks looming in the courtroom. There was only one such appointment he regretted, and it haunted him to the end. Who was to know, he said, on the available facts: it was the misjudgment of his life, which he hoped to outlive, but did not.

In 1997, the TRC invited representations regarding the legal system in South Africa from 1960 to 1994. It called for judges to appear before it. Chief Justice Mahomed was firm in response: he did not believe that it would be constitutionally right for judges to do that. But a number of judges, including him, former Chief Justice Corbett, Arthur Chaskalson and Pius Langa (as president and deputy president of the Constitutional Court) made detailed submissions. So did some individual judges, including Friedman.

He also pointedly criticised ‘hand-picked’ commissions of inquiry , and the misuse of judicial inquiries for political purposes.

He went to the heart of the issue: how could one accept appointment as a judge in the apartheid era? And if you had, why not resign?

In answer he referred pointedly to judges who had accepted appointment “without qualms about applying the apartheid laws”. But there were also those “who felt there was still room for the advancement of human rights [who] accepted appointment… and, having done so, decided not to resign”. They were aware that for some their presence “tended to lend legitimacy to the unjust system of apartheid”. For these, “weighing all the arguments for and against, they became in the belief that the contribution which they might be able to make would advance rather than retard the cause of justice and that they would be in a position to apply the unjust apartheid laws as humanely as possible within the parameters of their judicial oath”. He believed, he said, with his colleague Richard Goldstone, that a judge might freely speak in court on any issue strictly relevant to the matter before him”. Also to “criticise the law he was required to implement if, in his opinion, it offends against morality or justice. Indeed, in some cases it may be his duty to do so.”

He referred to instances where this had happened. Self-effacingly, not to his own. He also pointedly criticised “hand-picked” commissions of inquiry , and the misuse of judicial inquiries for political purposes.

In retirement from active service Friedman had no time for the opposition publicly expressed by a deputy minister of justice to retired judges serving in other capacities. For 11 demanding years, until he was 82, he did further public service as the chair of the Financial Services Appeal Board. For eight of those years he was also the chair of the Ombudsman’s Council, and from time to time he arbitrated weighty matters. He also served as a Judge of Appeal of the Kingdom of Lesotho.

Such was his sense of public service.

Another side

The severe court persona had another side. In private he could be irreverent and, unbending, very funny. He could mimic colleagues on the Bench, the senior advocate too whose moustache would droop when he sensed the court turning against him. Even the perilous fussing of his French bulldog, “Billy the Carguard”, around those parking at the house. Best of all, the frozen hauteur on the face of his Abyssinian cat going down the stairs and encountering a Kommetjie baboon on its way up.

In a full life Friedman played league then social tennis into his seventies, and held the Cape record for some years for landing the largest hammerhead shark. He is remembered for arriving home one evening in his elderly Lancia (he lived austerely in all other respects) with a massive tuna sitting next to him on the passenger seat. His family once tried vainly to find one outrageous thing he had done. His answer was that once he’d accepted a speaking role in a French farce put on at the Alliance Française. The next day he sent a message that he had remembered another: on a dare, on holiday with his wife and close friends at Beira, he had once swum nude.

Read more in Daily Maverick: In memory of human rights lawyer Priscilla Jana

Read more in Daily Maverick: In memory of George Bizos (1928-2020)

Yvonne Friedman predeceased him, in 2013. He had nursed her with great devotion. They had been integral to the setting up of the Woodside Sanctuary, a home for profoundly intellectually disabled children. It was an unsung devotion. At the height of apartheid he used his position in one respect: to get special permission for Woodside to admit children of all races.

Friedman had a strong sense of his roots. He chose however to be cremated, without ceremony. He is survived by his children, Kathy, Glynis, Laurence and Roger, and his grandchildren.

As he wrote of his friend and mentor, Mick Corbett, whose funeral oration he delivered, Friedman was himself greatly revered and highly respected. He leaves a void in other lives, and in the legal world to which he gave himself. DM

Jeremy Gauntlett is a senior counsel and King’s Counsel. He is a former chair of the Cape Bar and General Council of the Bar.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

RIP a Giant!

This is a wonderfully comprehensive, fitting, and elegant tribute to a remarkable man, and a reminder of the many servants of our legal system who kept alive a belief in the potential of the rule of law and the courts during the darkest days of our past. Thank you, Jeremy. I would add only one footnote: Judge Freidman really cared about legal education and young lawyers. Part of his Judge Presidency coincided with my term as Dean of the Faculty of Law at UCT, his alma mater, and Gerald was unfailingly supportive and interested in all the events to which he was invited. One episode in particular bears recording: when in mid-1994 we presented a series of weekly evening seminars introducing the transitional Bill of Rights to practitioners, I was a little perplexed that no judges initially signed up. The reason became clear when the Judge President wrote to me to explain that they would very much like to attend, but propriety required that they not have to pay for this opportunity (we used it as a means to raise funds for bursaries for our students), lest it be perceived as partisan support for one of the three faculties in the Western Cape. We naturally welcomed all the judges without charge, and Gerald led his fellow-judges to consistent attendance and engagement through the 12 week series. He was an inspiration to many.