Op-Ed

The Ubuntu Nation? Changing views on social solidarity and the Covid-19 pandemic

During the initial hard phase of the lockdown in April and May, South Africans were firmly of the view that the Covid-19 pandemic would promote solidarity around concern for the welfare of others during a time of national crisis. However, this ‘ubuntu moment’ appears to have been short-lived, with a sceptical outlook more prevalent during the latter part of lockdown Level 3 in July. In this article, we profile this shift, examine possible explanations, and reflect on the implications for the country post-pandemic.

Clear signs of an ubuntu ethic during the hard lockdown

The first round of the online University of Johannesburg-Human Sciences Research Council Covid-19 Democracy Survey, conducted between 13 April and 11 May, asked respondents: “In the immediate future, is the coronavirus pandemic more likely to make South Africans more united and supportive of each other, or more suspicious and less trusting of each other?”

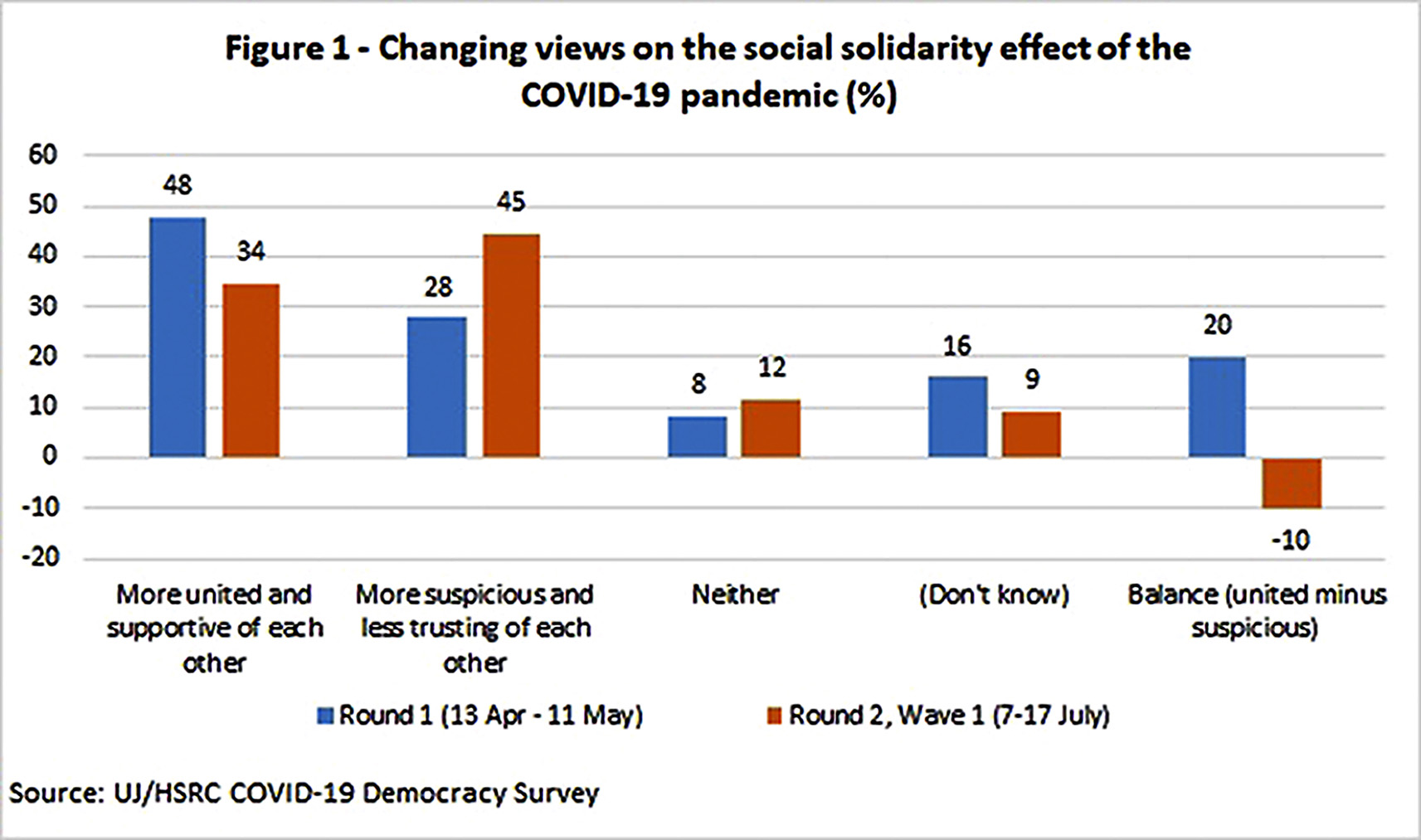

In response, 48% of respondents were optimistic that the crisis would lead to greater social solidarity, while 28% felt it would create further division in society.

This positive outlook was consistently observed, irrespective of the wide range of socio-demographic attributes examined. Looking at responses by gender, age, population group, educational attainment, employment status, subjective poverty status, personal income and type of accommodation, there was a broad uniformity in perspective, with a larger share believing in the unifying rather than the divisive effect of the pandemic.

There was a degree of group-based variation in how widespread the solidarity view was shared, ranging from a high of 54%-55% among the non-poor and those earning more than R20,000 per month to a low of 41% among students. But this does not detract from the overall message.

This dominance of the solidarity perspective suggests an ubuntu ideal of a caring, humane society informed the outlook of South Africans during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic. This was, after all, a period characterised by a substantial increase in charitable giving, with monetary contributions to social solidarity funds, in-kind support in the form of food parcels and other basic needs supplies, as well as the formation of community action networks. This was in line with past research indicating South Africans are a nation of social givers.

A broad-based change in outlook

There was a decisive change in public sentiment between Level 5 and lower levels of the national lockdown. By the time Phase 1 of Round 2 of our survey was conducted (8-17 July) and the solidarity question was replicated, the public’s primary response had switched from a fundamentally optimistic one to a critical and mostly negative stance.

The proportion who felt the pandemic would unite South Africans fell by 14 percentage points between the two survey rounds, whereas the pessimistic view grew by 17 percentage points. This change meant the leading view became one of division rather than solidarity (45% vs 28%).

This change in outlook was broad-based in nature, with a growing inclination towards the divided option occurring almost universally across the different personal characteristics described earlier. This signifies that a generalised scepticism emerged among South Africans between the initial hard lockdown period and the subsequent, less restrictive, lockdown phase.

What gives? Economic strain, leadership performance and political divisions

What might explain this changing predisposition among the public? We explore several lines of argument based on the survey data. These relate to economic vulnerability, loss of confidence in the leadership response to the pandemic, and the re-emergence of political fault-lines.

Economic strain

There is some evidence of an economic vulnerability effect, with those expressing economic distress during lockdown displaying a more substantive scepticism regarding a social solidarity effect resulting from the pandemic than those who report being relatively better off. Those who stated they and their family were poor or just getting by were significantly more likely to adopt the negative outlook relative to the self-rated non-poor.

Similarly, those reporting difficulty paying expenses during lockdown were more sombre in their views on social solidarity than those who were comfortably able to meet household expenses. Support for the economic duress argument is also found in the qualitative responses about economic difficulties provided by those respondents who feel the pandemic is going to polarise society further:

“We lost jobs we can’t provide our family it’s a disaster even social relief grant we don’t get it food parcel our leaders they judge by looking us they don’t know what is happening inside our homes”;

“Being jobless with no income, I’m only depending on my son’s grant and it’s not enough”;

“Work is closed and the bank doesn’t care and takes money out of people’s bank account even though you explain that you need that money to feed your family… work isn’t paying out the UIF money nor paying you the amount of money that you clearly worked hard for”.

Loss of confidence in leadership response to pandemic

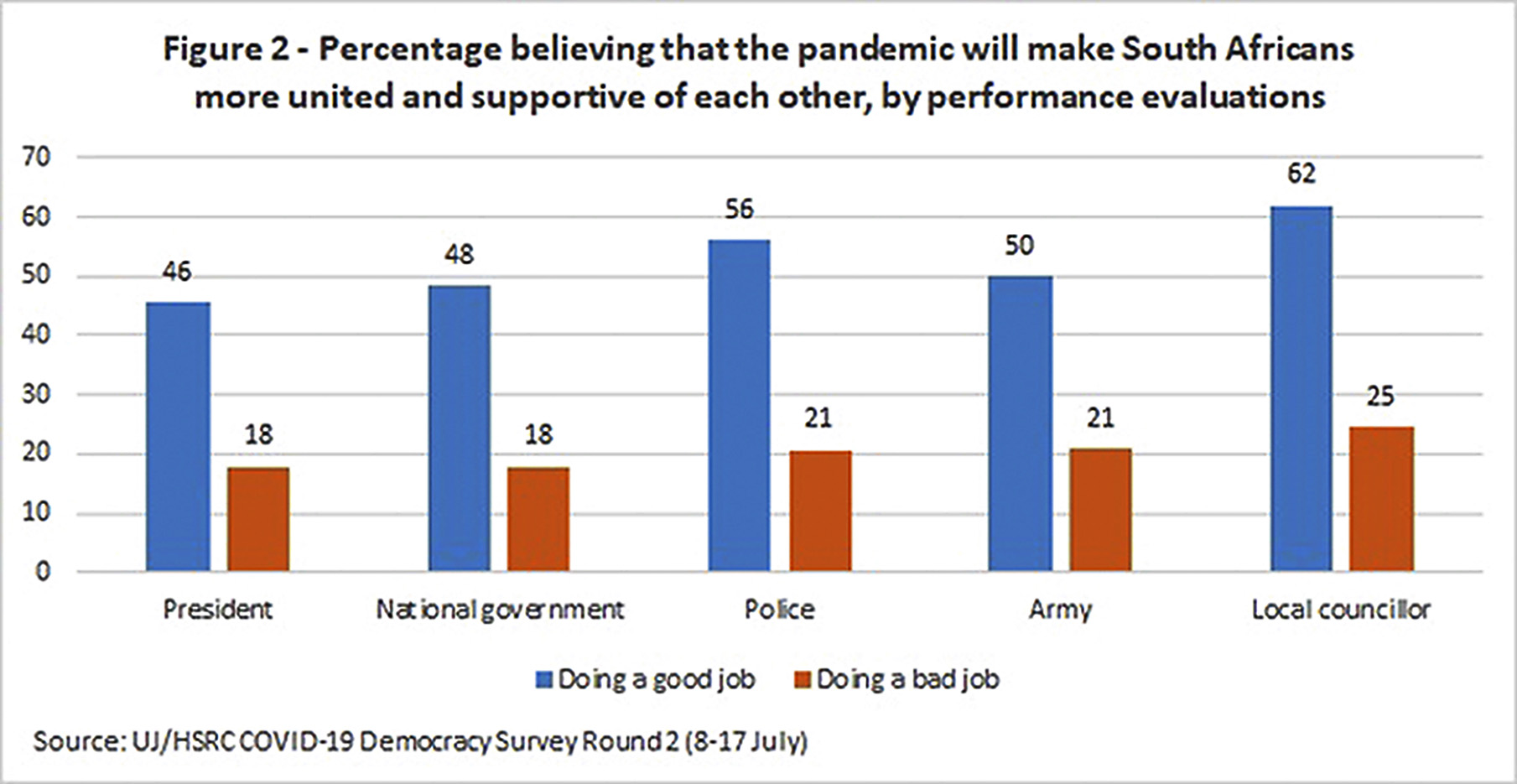

The survey further suggests that loss of confidence in the handling of the pandemic by the President, national government and local authorities is associated with the lower likelihood of believing that the pandemic will produce a more caring society. The scale of this is sizeable and applies across all institutions examined.

While this pattern applies equally to both Rounds 1 and 2 of the survey, the share providing negative performance ratings increased substantially between the two rounds for all except local councillors (where low trust was observed in both rounds).

Confidence in the President’s performance fell by 24 percentage points (from 85% to 61%), 21 percentage points for the police (from 51% to 30%), and 15 percentage points for the army (from 47% to 32%). The implication of this is that the greater numbers offering critical evaluations of the performance of these institutions contributed to the general swing in perspective from solidarity to polarisation. The confidence in local councillors remained very low (29% in Round 1, 24% in Round 2).

This finding raises the additional question of what prompted this harsher view of the handling of the pandemic response by these institutional actors.

A recent Daily Maverick article based on the data suggests that part of the answer lies in divisive regulatory policies, such as the tobacco and alcohol bans, as well as psychosocial strain as reflected in feelings of frustration, anger and depression. Other factors suggested by the qualitative data we collected are perceived problems in implementing emergency relief measures such as food parcels, coupled with concerns over corruption, as well as lack of preparedness as the confirmed Covid-19 cases and deaths surged. Some of these responses included the following:

“People not getting any help from the government and not getting the unemployment funds they promised to give them”;

“Knowing that many people are struggling to meet basic needs and government is not providing the support that is needed”;

“Food being expensive and no food parcels. Our councillor has not been of any help about hampers or food parcels”;

“I feel the government did not prepare enough, especially for the poor who are now suffering and have no food”;

“Make sure there is no corruption in the Covid response. If that fails, there must be severe punishment for those found to be corrupt in any area. The laissez-faire attitude towards corruption must stop”;

“Stop corruption and use that tax money to help our nation survive Covid”;

“Please save South Africa by fighting corruption and improving service delivery for the poorest people”.

Political faultlines

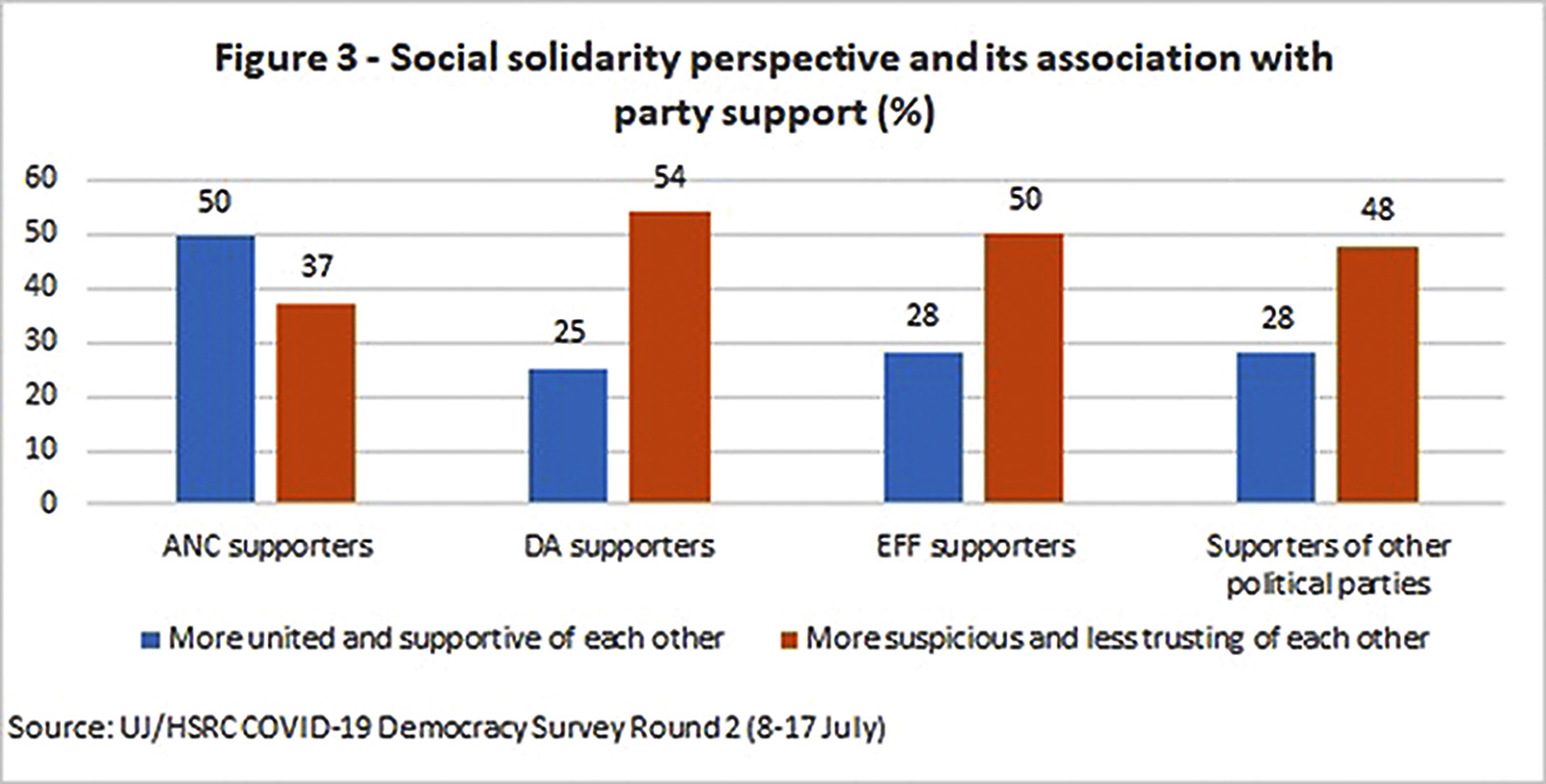

A final argument relates to the apparent re-emergence of political and other societal fault-lines after the hard lockdown phase. During the early weeks of the pandemic, there was broad consensus among political party leaders of the necessity of a hard lockdown to ensure that the health system was ready for a forthcoming spike in coronavirus cases. This support for the presidential decision, however, began to erode during lower levels of lockdown, with wide-ranging criticism of leadership decisions, the rationality of certain regulations such as the tobacco ban, the return to school, the economic consequences of lockdown, and alleged corruption.

Mirroring this growing political division over aspects of the national lockdown, we find significant public differences in views on social solidarity based on party support (Figure 3). While ANC supporters are generally more likely to favour the solidarity perspective on average, opposition party supporters tend to be more negative in their outlook. This clearly points to the resurfacing of political divisions in societal orientations that characterised the country prior to the Covid-19 crisis.

Spirit of togetherness

Having highlighted some of the statistically significant associations informing personal views on social solidarity during a time of national crisis, it is worth briefly outlining positive views of solidarity during the pandemic. The personal messages provided by respondents again speak to the role of observing collective action during the lockdown, confidence in leadership, and successfully receiving emergency relief:

“Seeing South Africans coming out and helping others by donating their time and money”;

“It has encouraged people to engage more and to band together to find solutions”;

“President keep the good job together with the minister of health to protect the lives of South Africans and everyone dwelling in your land”;

“You’re doing a great job. I wish South Africans can abide by the restrictions so that the hard work can be worth it all”;

“Thank you Mr President for increasing the grant money and also giving unemployment people grants we appreciate it”.

Government should therefore be encouraged to support civil society organisations working with vulnerable populations to leverage the trust that exists to promote behaviour change and the positive health practices needed to fight the Covid-19 pandemic. This spirit of togetherness can also be enhanced if government leaders mirror the behaviours they expect of their citizens. For instance, wearing masks and respecting social distancing during public meetings and gatherings will improve trust between government officials and citizens.

An ubuntu notion rather than the ubuntu nation?

The experiences of the past five months have clearly seen the public’s hope that the pandemic will lead to a coming together of citizens against a common existential threat increasingly being replaced by a more circumspect view. This reflects a combination of adverse personal circumstances and experience, growing negativity about the quality of leadership and governance during the pandemic, and a loss of political unity. This suggests that, for now, the ubuntu ethic remains more notional than evident in practice for many South Africans. This is reflected in survey evidence from the HSRC’s South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) series, which demonstrates that low levels of social trust have persisted in the country over the last two decades.

However, the rallying together that patently occurred during the early phase of the lockdown — and arguably since — remains a telling reminder that a different kind of society is possible. A social compact framed around a collective emphasis on helping others — a hallmark of ubuntu as a moral theory — is needed now more than ever in order to address the new and existing vulnerabilities that will confront the post-pandemic society.

While we are optimistic about our ubuntu nation, we acknowledge the tensions that exist between individual and collective priorities. The Constitution of South Africa and its underlying values are strongly informed and shaped by the African conception of ubuntu. This emphasises a communitarian ethic and mutual obligation to the community rather than individual rights and entitlements, and may serve as a framework that encourages new ways of living together and, thus, the potential for social renewal. DM/MC

Benjamin Roberts is chief research specialist, Yul Derek Davids a research director, and Narnia Bohler-Muller divisional executive in the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division at the HSRC. Kate Alexander is a professor of sociology, South African Research Chair in Social Change and director of the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg. Ngqapheli Mchunu and Yamkela Majikijela are PhD researchers in the DCES research division of the HSRC.

Data were collected in the online multilingual UJ/HSRC Covid-19 Democracy Lockdown Survey from all willing respondents in South Africa aged 18 or over. The survey was administered using the #datafree Moya Messenger App on the #datafree biNu platform, or alternatively using data via https://hsrc.datafree.co/r/ujhsrc. Results are weighted by age, population group and education, making them broadly indicative of the attitudes and behaviour of the population.

A summary of the survey’s Round 1 and 2 findings and a fuller explanation of the methodology can be found at:

http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/media-briefs/ceo/hsrc-uj-release-finding-multilingual-Covid19-survey.

The following articles based on Round 2 of the UJ-HSRC Coid-19 Democracy Survey data have been published in Daily Maverick to date:

How the Covid-19 lockdown impacted on SA’s mental health

Human rights sacrifices during the pandemic: Who and Why?

Masks – Who wears them and Why it matters

The Calculus of Trust: Diminished public confidence in the president’s performance

Smoke and mirrors? Public perceptions on banning the sale of cigarettes

Survey shows government’s schools policy is opposed by a large majority

Links to previous Daily Maverick articles based on Round 1 of the survey data are:

Unlocking the public’s preferences: What South Africans think of lockdown and policy responses

‘We are getting cold’: Lifting of clothing-sale ban comes not a moment too soon

Up in Smoke: Public reflections on decision to extend the ban on tobacco sales

Human rights remain essential during the Covid-19 crisis

Reopening of schools: Bold leadership and planning required

Calls for bolder action as lockdown exposes fault lines of inequality

‘Hungry — we are starving at home’

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s job performance

The hidden struggle: The mental health effects of the Covid-19 lockdown in South Africa

Class and the Covid-19 crisis: questions of convergence and divergence

Survey shows government’s schools policy is opposed by a large majority

Smoke and mirrors: Public perceptions on banning the sale of cigarettes

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider