Maverick Citizen Op-Ed

How the Covid-19 lockdown impacted on SA’s mental health

A survey was conducted in July by the University of Johannesburg and the Human Sciences Research Council on how the mental health of South Africans fared under two months of stages 4 and 3 Covid-19 lockdown. It found psychological distress had decreased significantly among black South Africans compared to whites, and identified reasons for the difference.

In May, our University of Johannesburg (UJ) and Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) Democracy Survey project presented baseline empirical evidence of South Africans’ mental health following the onset of Covid-19 in South Africa.

Following two months of infections, deaths and what a recent Economist writer called, “a pandemic of psychological pain”, we gathered data in a follow-up survey in early July. We again have a sizeable nationwide sample weighted to Stats SA data by race, age and education.

We can now examine the changes in mental health that have occurred, and how their drivers may vary across our highly unequal and diverse society.

Our soundings were necessarily brief, being gathered mainly via smartphones. But the scientific literature is reassuring that one-item scales, for example for depression, are impressively sensitive and specific.

We said: “Now we want to ask you a question about the effect of the lockdown on you emotionally. Which of the following emotions have you felt often during the past week?” We posed the question for stress, fear, frustration, depression, sadness and anger.

The relevance of these options had been confirmed by the many write-in comments from respondents in our previous survey. (We also covered loneliness and boredom, but these turned out to need separate analysis, and are not considered here.)

Psychological distress decreases overall

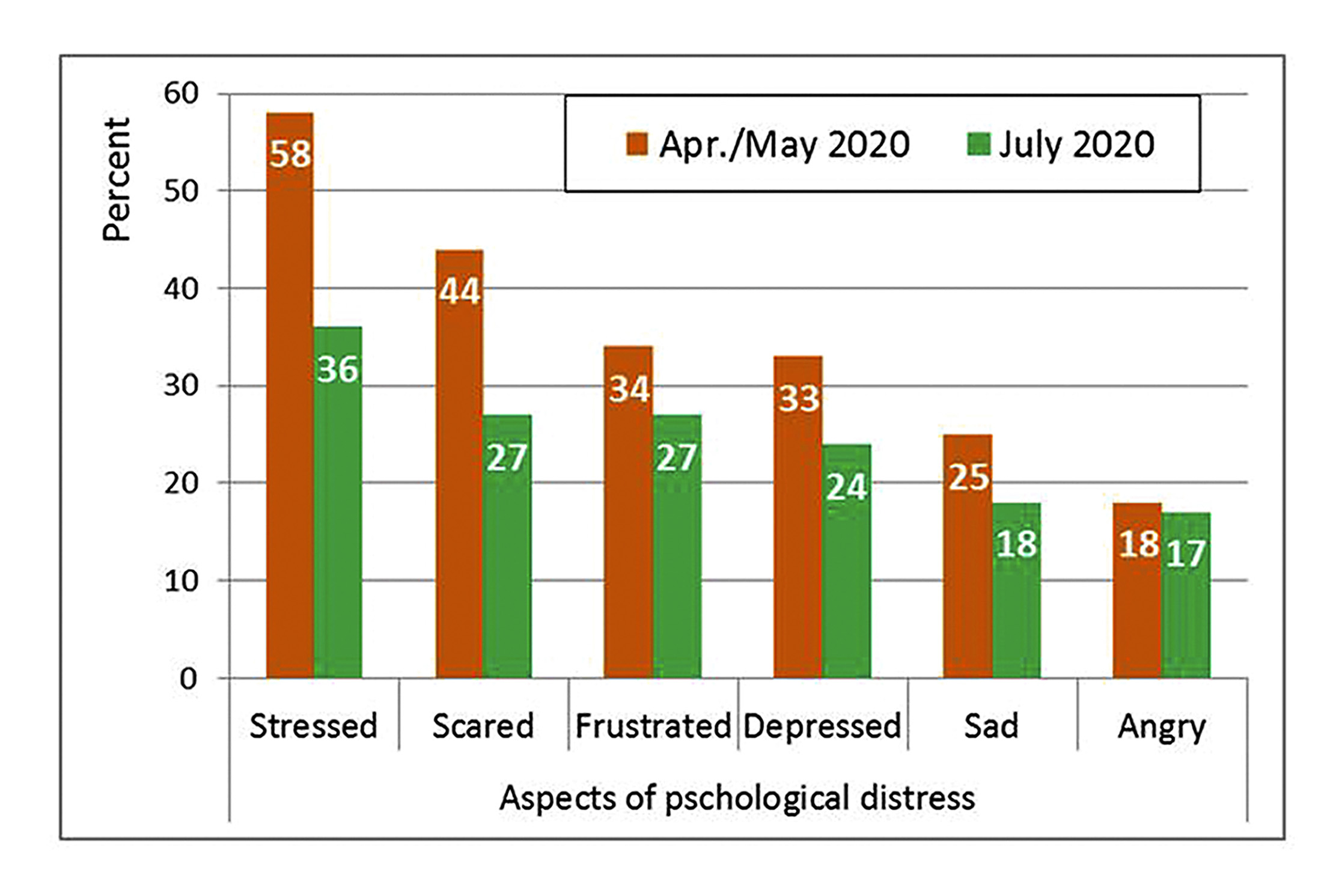

The proportions we found previously, in April/May, ranged from as much as 58% of people feeling stressed, through 33% depressed, down to 18% angry. They are all shown as the left-hand bar of each pair in Graph 1.

After two months of lockdown, the first unexpected finding is that fewer South Africans overall have reported feeling stressed, depressed, or any other of these six emotions. For example, the proportion of people experiencing stress dropped from 58% down to 36%, a drop of 22 percentage points. (The phrase “percentage points” refers to the difference between two percentages. We’ll call it “pp.”)

The other percentage point differences were fear, 17pp; depression, 11pp; and frustration and sadness, 7pp. Only for anger was the decrease negligible — just 1pp. The right-hand bar in each pair in Graph 1 shows the recent values.

Graph 1: Six ‘moods’ under lockdown, comparing April/May and July.

To investigate further, some simplification is necessary. In our earlier report, statistical analysis indicated that the six emotions could generally be analysed together. We labelled this composite “emotionally distressed”. This is also a valid move in the newer data, and allows us to grasp the big picture changes during the lockdown. (Remember that if, say, one third of a group say they are distressed, this also means that two thirds are not!)

Grouped in this way, the overall proportion of emotionally distressed South Africans drops by 12 percentage points from 44% down to 32%. (In a roughly analogous finding in the US, the Gallup Poll reported a similar drop in the proportion of “worried” people between late March and late May.)

How might this welcome development have occurred? In South Africa, statistics can be especially deceptive given the enduring apartheid legacies of inequality in various respects, especially between whites and the other race groups. When the results are broken down in this way, a significant contrast indeed emerges – our second unexpected finding.

The decrease in distress is among blacks, but not whites

For the five left-most emotions shown in the graph, statistically significant decreases in distress were shown by black Africans, coloureds and Indians/Asians alike. But whites remain unchanged – as high a proportion of stressed, scared, frustrated, depressed and sad respondents as in our earlier survey. And in the sixth respect, the angry proportion remained unchanged among blacks, but increased markedly among whites. (We apologise for the terse race-group terminology. It’s for constructive statistical purposes.)

Aggregating these changes with the composite variable, we see that over the two-month lockdown, the proportion of blacks who were distressed decreased strongly from 43% down to 29%, whereas among whites it increased slightly, from 56% to 60%. Alternatively put, psychological distress decreased among blacks by 14 percentage points, and increased among whites by four percentage points.

The challenge, then, is to establish, from among the many items in our survey, through which circumstances, or shifts of attitude, mental distress was altered so disparately between white and black adults over the two months. A technique called log-linear analysis helped with the sifting.

It turns out that the black-white disparity manifested in two ways. One was where the distressed proportion in the white sub-group increased only slightly, but fell sharply in the black sub-group, over the two months.

So, among black adults, the distressed proportion decreased by 19pp for those who were employed (or not in the labour market); decreased by 17pp for those older than 35; and decreased by 16pp for those who did not experience water access (or electricity) issues.

By contrast, among white adults, the distressed proportion increased by a few percentage points in these respects. This made the main contribution to the overall difference.

The other way in which the black-white contrast manifested was where the distressed proportion actually increased among both groups over the two months, but far less among blacks than whites. Thus, for people seeking an end to the cigarette ban, distress increased by only 7pp among blacks, versus 19pp among whites; by five vs 20pp increase in distress among those lucky enough to spend the time in formal dwellings; and by six vs 23pp for those objecting to diminished human rights.

Some of these variables may seem unfamiliar. But recall that we are dealing with different changes in antecedents of the different changes in distress among the two groups. In the more usual analyses of a single survey, “a snapshot in time” – other variables were relevant, such as income or hunger, education, and sex.

Views on the six factors were vigorously expressed in the write-in question: “For you personally, what is the worst thing about the lockdown?” But remember that each distress statistic has its complement. We also asked for “the best thing” about lockdown. Just one illustration of each, for the six predictors of mood change, is a reminder of the different lives and contrasting views gathered.

Employment: “Those who live on the streets no longer hustle or eat bcuz of lockdown.” “I still get a salary and have a job.”

Water access: “Being unable to keep up with good hygiene standards due to lack of water.” “Social distance, washing of hands and sanitising.”

Housing: “Two rooms with 9 people including 2 kids.” “Working from home, no traffic.”

The cigarette ban: “The fact that I have to pay a hellish price for cigarettes and have to slink around like a smuggler to buy.” “That cigarettes are not being sold any more.”

Human rights: “When we hear about police and SANDF misbehaving and killing our people.” “Police and army protect us, we stay safe in our homes.”

Age: “It’s hard for the children, they don’t understand the reason of the pandemic.” “We get to spend time with family and do a lot of reading, meditation, home workouts.’

Resilience, properly understood

The changes on these half-dozen factors give us the what: what induced most to the lesser proportions of overall distress among blacks in comparison to whites after two months of lockdown? There remains a deeper question of why. Why, for example, should the distressed proportion have decreased for blacks but not whites among those who stayed employed? Why should it have risen much less for blacks than whites for families in formal housing?

The concept that comes to mind is resilience – the capacity to endure and cope with adversity, even to bounce back. Resilience may be partly individual “grit”, but, as the qualitative evidence underlines, it is much more about people in the context of their families and communities.

US researchers recently found that African-Americans have better mental health under Covid-19 than whites. They suggest this could be rooted in “a historical trajectory of overcoming adversity, strong community ties, and continued belief in the promise of education”. Local literature adds the diverse forms of extended or multigenerational families, especially among black South Africans, and the support they can provide.

But these kinds of explanations fail “to include the racial inequities, systemic issues, and racism… faced in developing positive resilience”, and in particular don’t speak “to what could be called a state of generalised precariousness, which tends to characterise poor communities, where shocks and stresses are a part of daily life, not once-off blows”.

However, the welcome improvements in mental health evidenced in our follow-up survey suggests that these criticisms need, in turn, to be alert to unexpected wellsprings of resilience arising from the diverse situations, beliefs, and responses of families and communities – even amid the “collective trauma” of the Covid-19 pandemic. DM/MC

Dr Mark Orkin is an associate research fellow at the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg, Ngqapheli Mchunu a PhD intern of the Developmental, Capable and Ethical State (DCES) research division at the HSRC (Human Sciences Research Council), Kelebohile Afrika an MA-candidate at the Centre for Social Change at UJ (University of Johannesburg), Narnia Bohler-Muller is divisional executive of DCES at HSRC and Professor Kate Alexander the director CSC at UJ.

Data has been collected in the online multilingual UJ/HSRC Covid-19 Democracy Lockdown Survey from all willing respondents in South Africa aged 18 or over. The survey was accessible using the #datafree Moya Messenger App on the #datafree biNu platform, or alternatively using data via https://hsrc.datafree.co/r/ujhsrc. Results are weighted to Stats SA profiles by age, population group and education, making them broadly representative of the population. A fuller explanation of the sampling can be found at: http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/12241/Weighting%20successive%20waves%20of%20the%20UJ-HSRC%20Covid-Lockdown%20survey.pdf

A summary of the latest survey’s findings, and links to articles from the earlier survey, are at the following link (click Cancel at the request for a username and p/w, and then OK): https://www.uj.ac.za/newandevents/Documents/2020-08-19%201300pm%20Coronavirus%20Impact%20Survey%20Round%202%20summary%20national%20results%20v4.pdf

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider