SOUTH AFRICA’S GREAT ESCAPE PART SEVEN

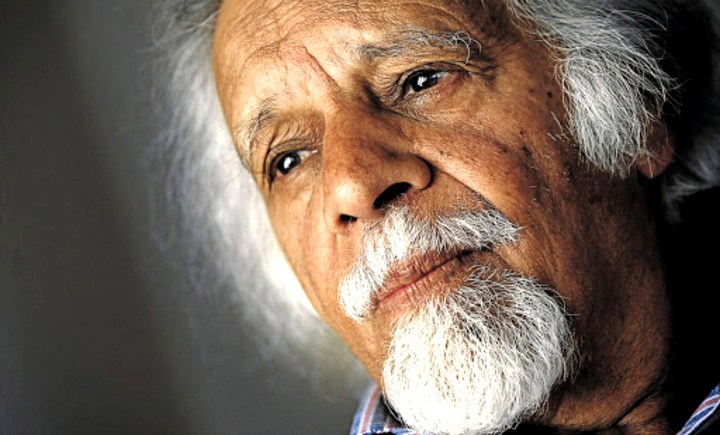

Marshall Square escapee Mosie Moolla’s life carries powerful lessons to be celebrated and shared

As the heroes of South Africa’s liberation struggle leave us one by one, their powerful stories of service and bravery need to be heard by a millennial generation that stands to be inspired and guided - and benefit - greatly.

11 August 2023 marks the 60th anniversary of what is known as the Great Escape. To commemorate one of the most successful jailbreaks in South African history and the many struggle activists who fought for a democratic South Africa, Daily Maverick is publishing a series of articles and reflections by relatives, friends and comrades of those involved.

These articles, all written by people linked in some way to the struggle, are personal accounts of their or their family’s involvement, and the impact that involvement had on their lives.

Read Part 1: here

Read Part 2: here

Read Part 3: here

Read Part 4: here

Read Part 5: here

Read Part 6: here

*

Funeral and memorial services of struggle icons provide profound lessons in history, and the memorial service of Moosa “Mosie” Moolla on 1 April this year was no exception. The service, organised by the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation, was a wonderful celebration of Moolla’s outstanding life of service.

Born in the small town of Christiana in then Western Transvaal, Moolla started his lifelong political career as a Transvaal Indian Congress activist, and participated in the major political campaigns of the fifties. His organising skills led to his deployment to the Secretariat of the Congress of the People Campaign, in which he worked alongside Walter Sisulu, Joe Slovo, Rusty Bernstein and Yusuf Cachalia. He was one of 155 activists charged with treason in December 1956, and one of 30 who remained on trial until the final acquittal in March 1961.

Stories such as the Marshall Square escape provides scripts that are as exciting as any that Hollywood can provide.

On 10 May 1963, Moolla was among the first to be detained under the notorious General Law Amendment Act number 37 of 1963, passed on 1 May 1963. Commonly known as the 90-Day Detention Act, it allowed the state to hold suspects for 90 days without charging them. He was among the first to be severely tortured in custody.

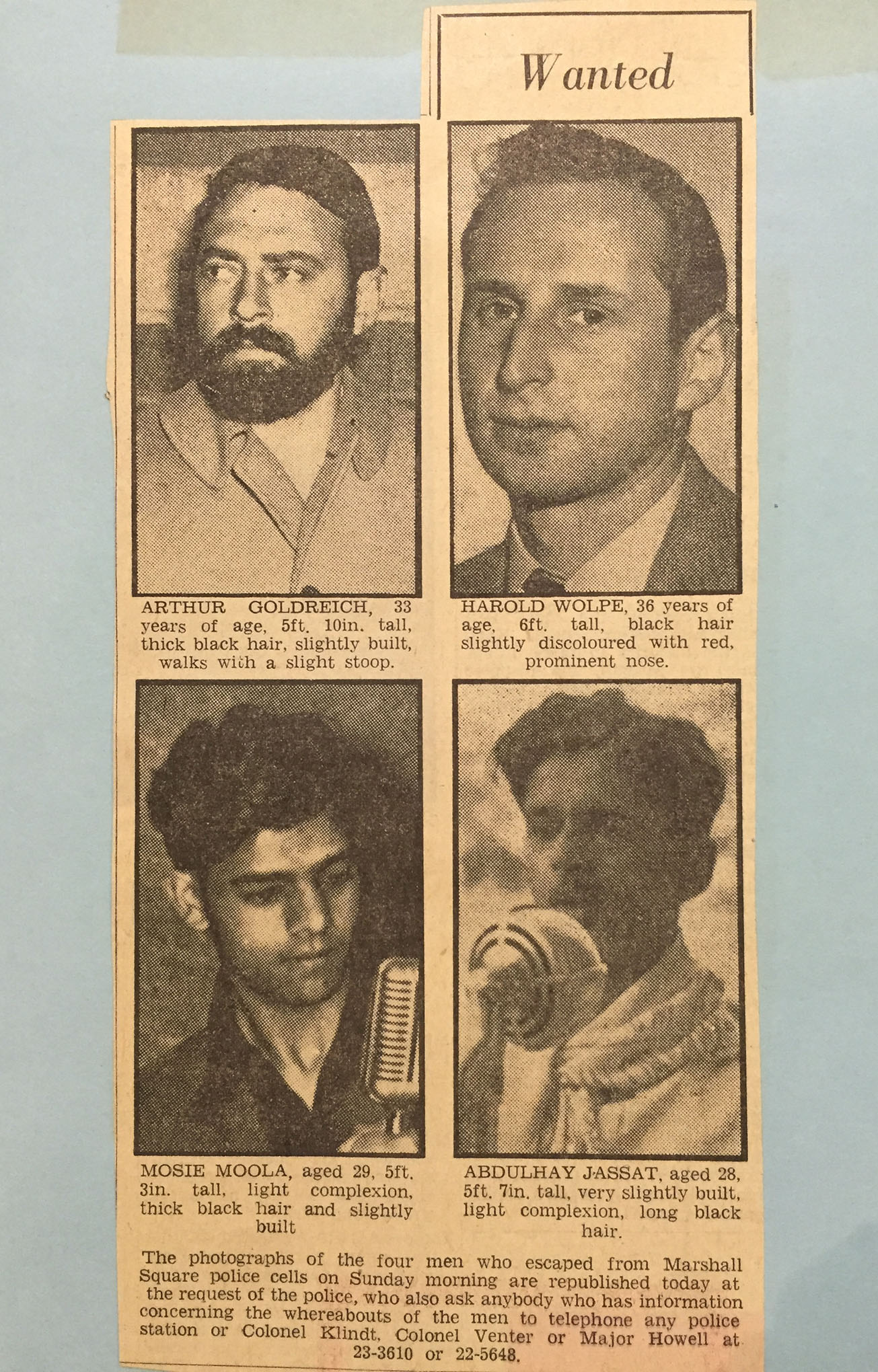

Also detained at Marshall Square Police Station at the same time was Moolla’s comrade Abdulhay Jassat; Harold Wolpe, a lawyer who had recently defended them; and Arthur Goldreich, who had been arrested during the Rivonia Raid on 11 July.

Goldreich, Wolpe, Moolla and Jassat. The police were hoping for information and even offered a reward for news on their whereabouts. (Image: Supplied)

The movement’s comeback

The arrests of Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada and others at Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, Johannesburg, had sparked an orgy of self-praise and congratulation in the apartheid security establishment. Moolla, Jassat, Wolpe and Goldreich put a dampener on their celebrations by staging a daring escape from prison, and successfully escaping into exile.

The Marshall Square escape was a boost to the morale of the liberation movement at a time of extreme repression and deep gloom. It demonstrated that, contrary to its claim, the apartheid regime had not managed to “smash all subversive elements”.

Mosie underwent military training in what was then Soviet Union, after which he served as ANC representative in India, Egypt and Finland. He was joined by his wife, Zubeida, and youngest son in exile, and suffered the pain of separation from his two children left in the care of Zubeida’s parents in South Africa.

It would be 28 years before Mosie could return to South Africa, in December 1990. He was a key member of the ANC’s Department of International Relations, and went on to serve as South Africa’s ambassador to Iran (1995 to 2000) and High Commissioner to Pakistan (June 2000 to 2004). For his dedication, commitment and excellent representation of South Africa in the international community, the Order of Luthuli in Silver was conferred upon him in 2013.

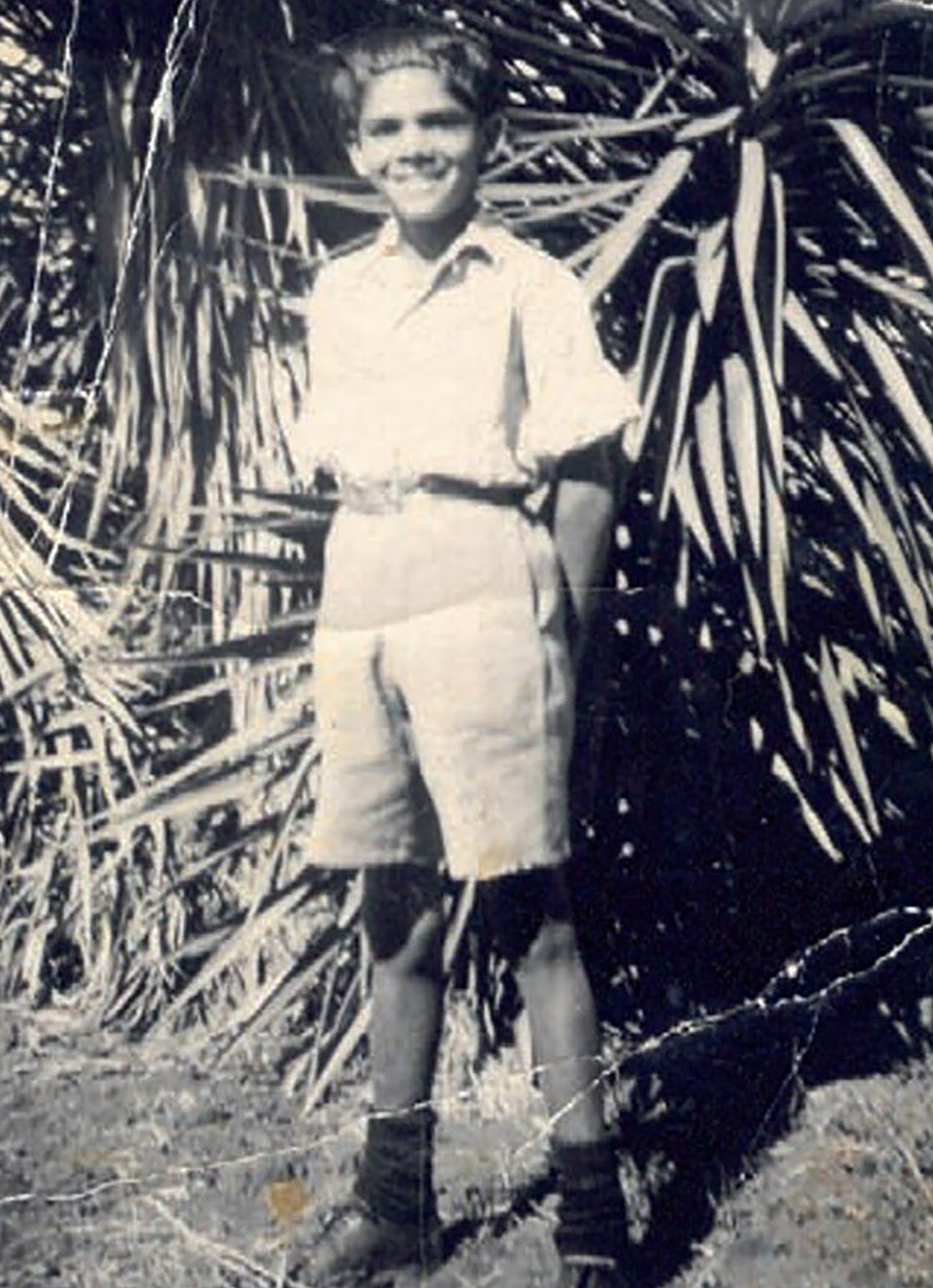

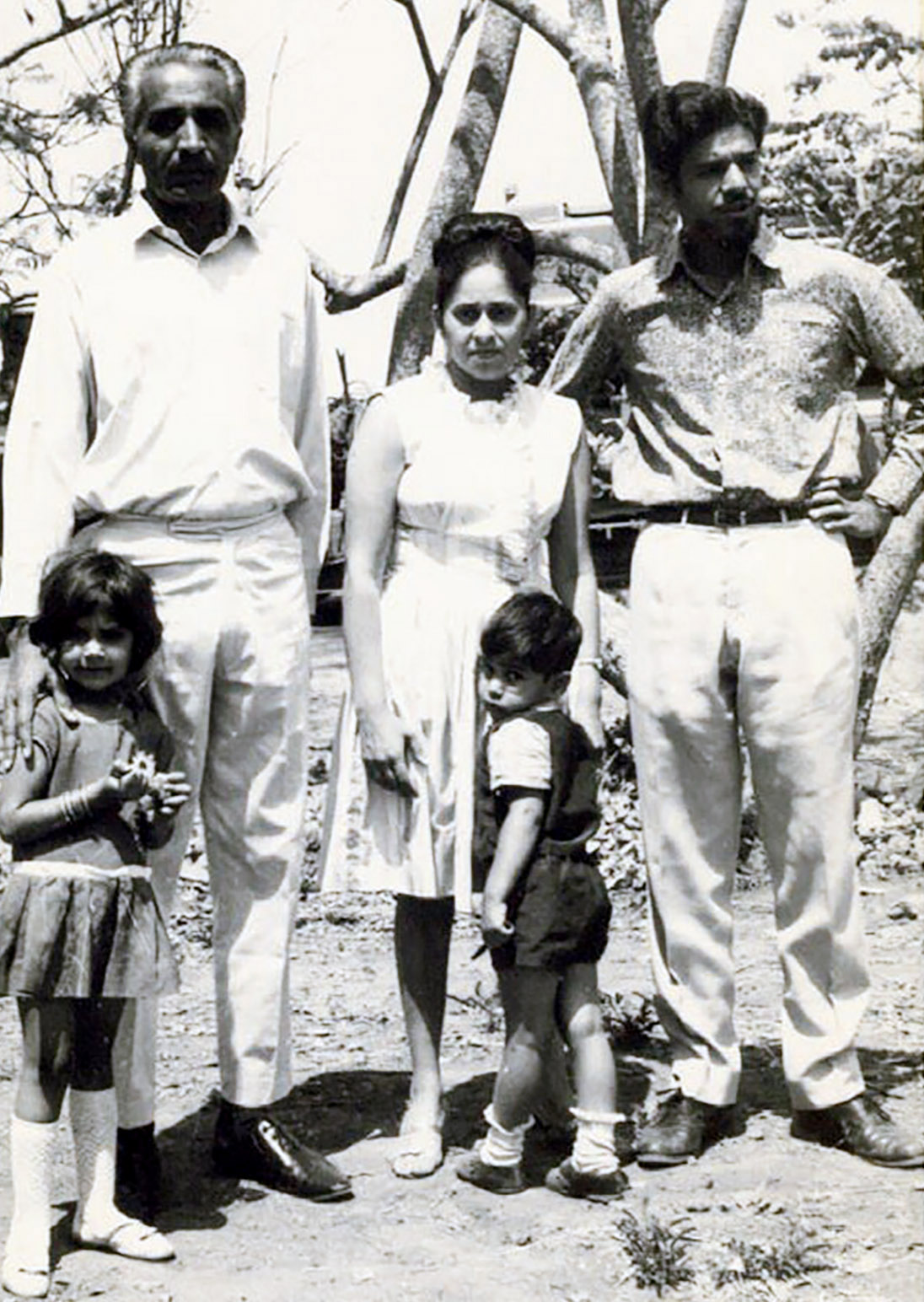

Mosie as a young child. (Photo: Supplied)

Jassat the only one left standing

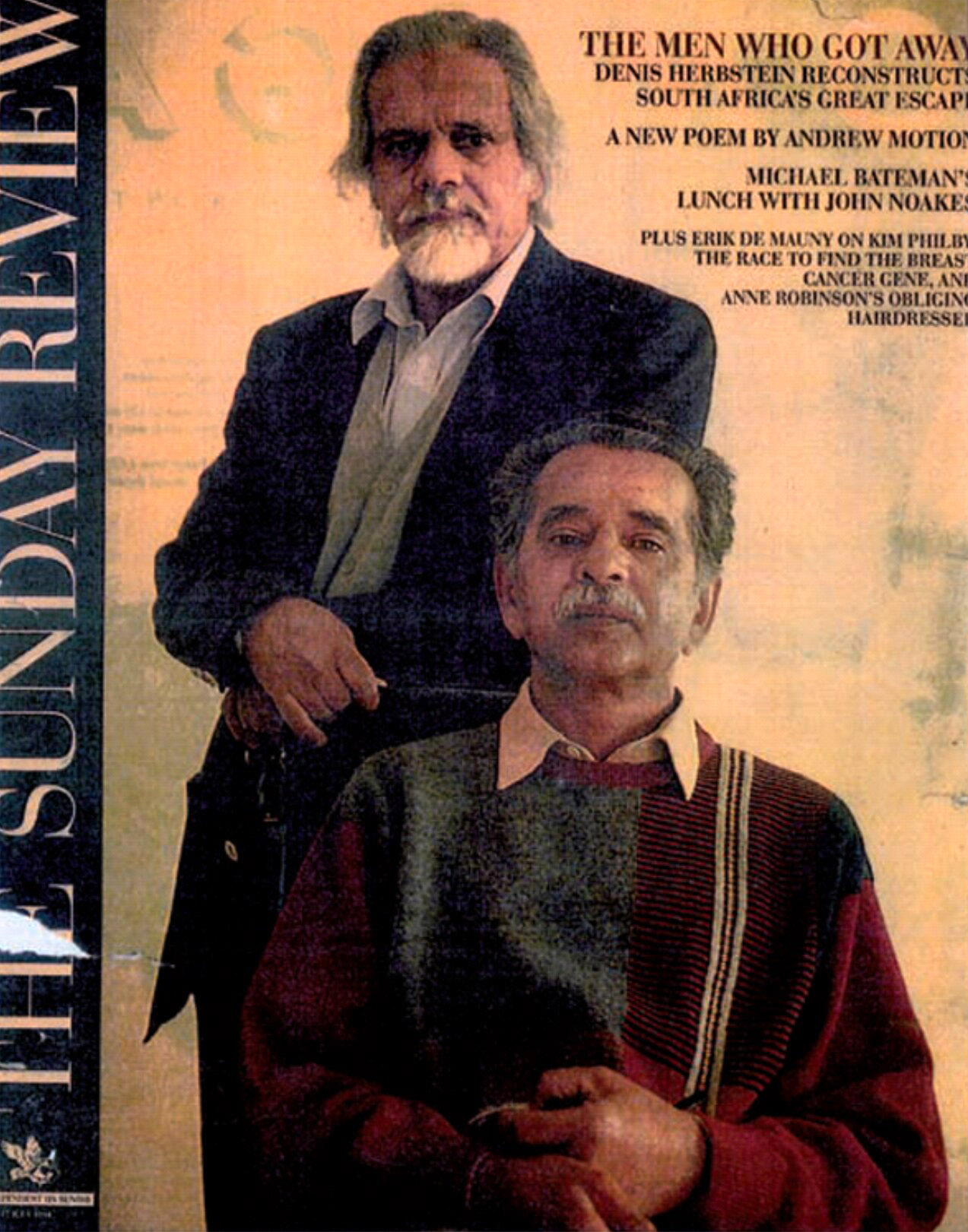

With the passing of Wolpe in 1996, Goldreich in 2011, and of Moolla on 25 March 2023, Jassat is the only living member of the quartet who staged that daring and dramatic escape in July 1963.

As we listened to Jassat paying tribute to his comrade and recounting the story of the escape, my husband Max and I reflected on his experience during that period. On 19 June 1953, his mother, struggle veteran Albertina Sisulu, had become the first person detained under the newly promulgated 90-day law. A 17-year-old Max became the youngest 90-day detainee a few days later, when he was arrested and taken to Marshall Square.

Mother and son were interrogated on the whereabouts of Walter, Albertina’s husband and Max’s father, who had gone underground. An article on Albertina’s arrest in a June 1963 edition of Durban newspaper The Post carried a scathing condemnation of the inhumanity of a detention law that harmed the children of detained people. The article was accompanied by a picture of a woebegone Beryl, Lindiwe and Zwelakhe, left to fend for themselves in the absence of their parents and eldest brother.

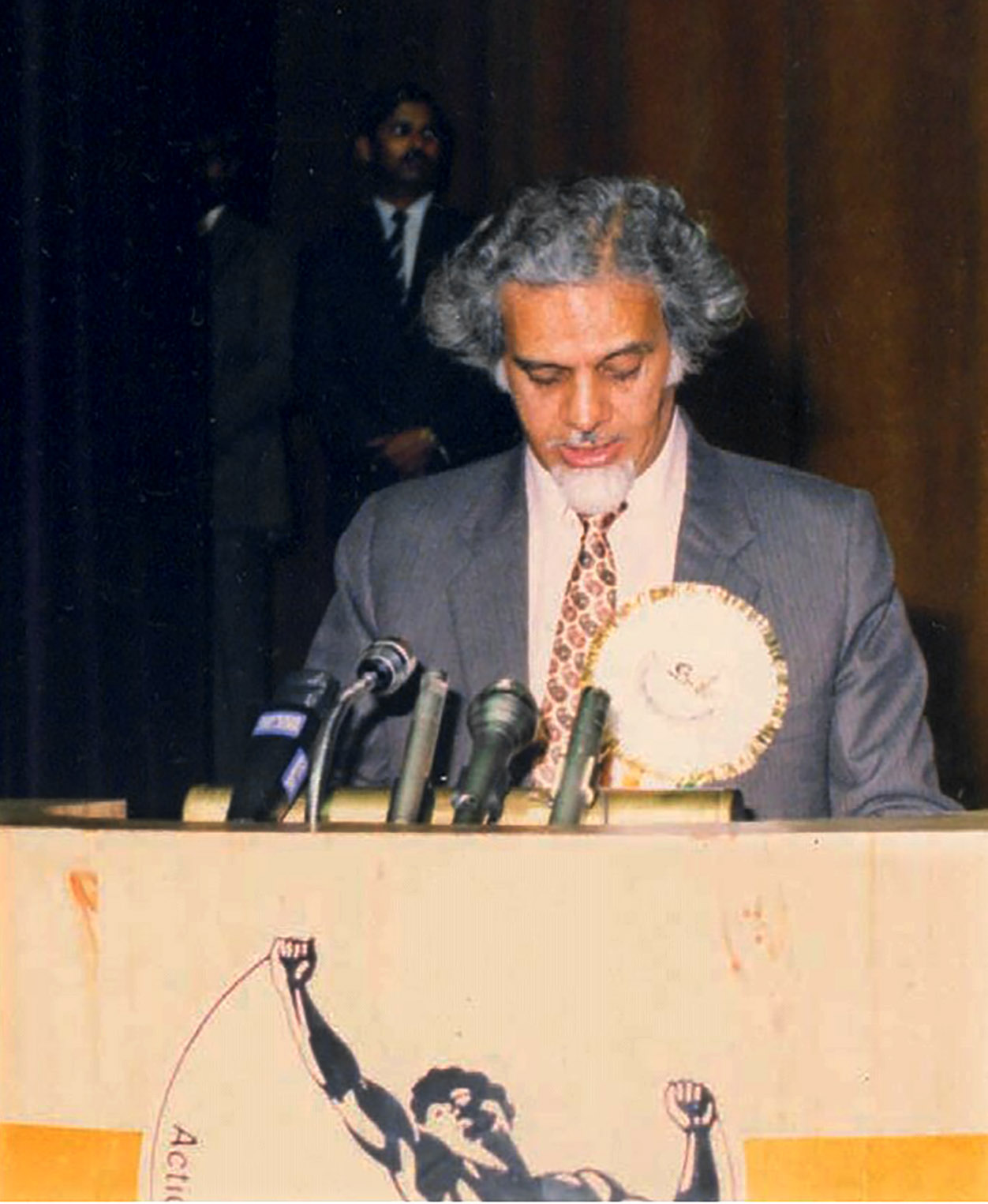

Afzal Moolla paying tribute to his father Mosie. The story of Mosie’s escape with Abdulhay Jassat, Harold Wolpe and Arthur Goldreich was featured in The Sunday Review and Sunday Independent in 1994. (Image: Supplied)

The exile journey

Max was released a week after the Rivonia arrests, and Albertina a couple of weeks later. Concerned that the police would continue to hound Max, Albertina supported the ANC’s suggestion that he go into exile. She watched him leave home on a cold August afternoon, a few days before his eighteenth birthday, with no idea that it would be 27 years before he could return home.

Max was part of a small group of young people who were smuggled into Botswana, where they were taken to a refugee camp in Francistown, to await further transportation to Tanzania. In the meantime, Wolpe and Goldreich had fled to then Swaziland (now Eswatini), disguised as priests. They were flown to Lobatse, Botswana, in a plane chartered by the brilliant defence lawyer Vernon Berrangé.

The East African Airways Dakota that was to take them to Tanzania landed in Francistown on 28 August, in readiness to leave the next morning. However, the plane was destroyed by a mysterious fire during the night. It was widely believed to be an act of sabotage by the apartheid regime.

Taken in Tunduma, at the Tanzania and Zambia border. From left: Alibhai, a friend Zubeida, Mosie and their children Tasneem and Azad, in 1968. (Photo: Supplied)

Soviet Union military training

Max was part of a group scheduled to be on the flight that night, as were Moolla and Jassat. Anxious to start military training, Max had been looking forward to Tanzania, so he was deeply disappointed to hear of the delayed departure. Due to the security risks, flights had to be rearranged, and Wolpe and Goldreich were flown to Dar es Salaam via Congo.

A few days later, the other refugees, including Max, were flown in separate planes to Dar es Salaam, where he stayed until he was sent to the Soviet Union for military training. Whenever Max met Moolla and Jassat, he would joke: “You guys caused our plane to be burnt down.” And Moola would reply: “No, you’re the skelm that caused the problem!”

One of the speakers at Moosa’s memorial was Barbara Masekela, former diplomat, cultural activist, author and educator. She remarked on Moosa’s extraordinary history, and bemoaned the fact that there were so few young people in the audience to listen to the accounts of his remarkable life. She articulated my long-held concern that we are failing to transfer historical knowledge to current and future generations.

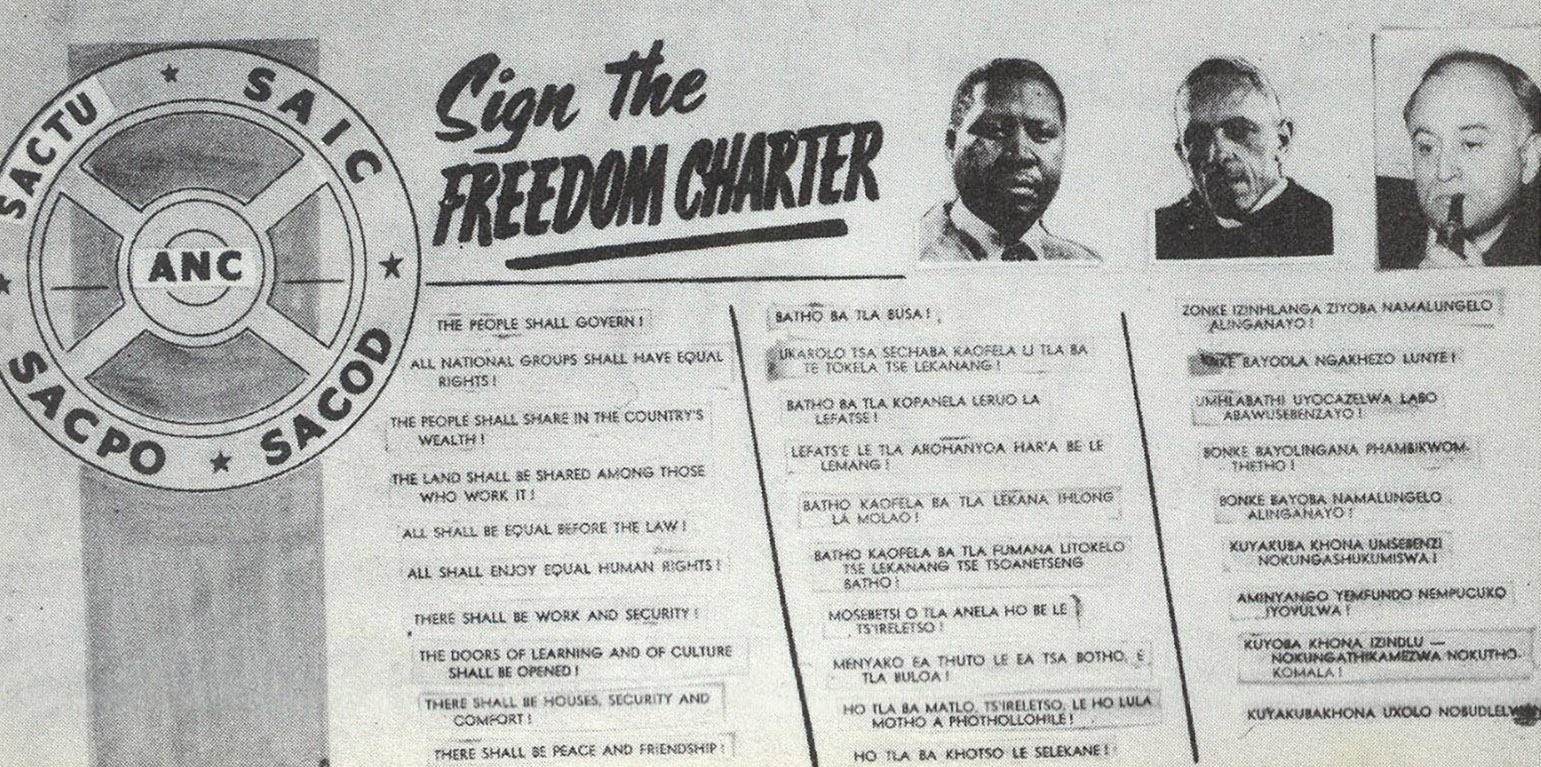

The Freedom Charter was adopted at the Congress of the People in Kliptown, in June 1955. (Image: Supplied)

What are we doing to keep history alive?

Our living history is fast disappearing, and what are we doing about it? In one of our many conversations on this topic with my sister-in-law Sheila Sisulu, I expressed surprise about the lack of basic historical knowledge among children in our family. She responded: “Because we don’t tell them about it. We expect them to learn family history through osmosis.”

I recalled this response a few years ago, when I attended the screening of An Act of Defiance, the film about the life of Bram Fischer by Dutch director Jean van de Velde. The organisers of the screening had the good sense to bus in a group of young people from Bram Fischerville, an informal settlement on the outskirts of Johannesburg.

The youngsters were profoundly moved by the story. They knew the place where they lived was named after a great man, but had no idea just how great he had been. They were also moved by the fact that an Afrikaner could sacrifice his life for the liberation of black people.

Take that, Hollywood!

This series of articles commemorating the 1963 escape is one way of keeping that history alive, but it is sadly not enough. History is not a compulsory subject in schools, and the lack of reading culture in our country means that young people are not reading the many books documenting the liberation struggle.

Mosie addressing the International Youth Conference Against Apartheid, New Delhi, India, January 1987. (Photo: Supplied)

My dream is for a series of docudramas entitled 1963 to come into being. That would capture the interlinking dramas that played out in 1963. It’s the stuff of legend for the generation that grew up in the liberation struggle, but they have not been made accessible enough for the millennial generation.

As we lament the paucity of contemporary leadership, we need to give our young people content to inspire them. Stories such as the Marshall Square escape provides scripts that are as exciting as any that Hollywood can provide. DM

Zimbabwe-born writer and human rights activist Elinor Sisulu is the author of the children’s book The Day Gogo Went to Vote (1997) and the biography of her parents-in-law Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime (2003). She is a founder member and current Executive Director of the Puku Children’s Literature Foundation.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.