SOUTH AFRICA’S GREAT ESCAPE PART SIX

How that great escape bolstered my determination to join the ‘Spear of the Nation’ struggle

An uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) and African National Congress (ANC) veteran looks back at his early days of resistance, his journey into exile and military training, and the influence the four Marshall Square escapees had on his resolve to join the armed struggle.

11 August, 2023 marks the sixtieth anniversary of what is known as the Great Escape. To commemorate one of the most successful jailbreaks in South African history and the many struggle activists who fought for a democratic South Africa, Daily Maverick is publishing a series of articles and reflections by relatives, friends and comrades of those involved.

These articles, all written by people linked in some way to the struggle, are personal accounts of their or their family’s involvement, and the impact that involvement had on their lives.

Read Part 1: here

Read Part 2: here

Read Part 3: here

Read Part 4: here

Read Part 5: here

*

This is the story of how the trajectory of my life’s journey was altered by the arrest of the top leadership of the ANC, the Communist Party of South Africa and MK, at Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, on 11 July 1963. It begins with the banning of the ANC on 8 April 1960, to which Nelson Mandela responded with emphatic defiance, asserting that the anti-apartheid struggle would continue until its objectives were realised.

Pursuant to Mandela’s declaration, the ANC went underground and reconfigured itself into several structural formations, including one based on five-person cells that functioned independently and in isolation of each other. This was done to optimise the security of operatives tasked with carrying out political work, the raison d’être for the organisation proscribed by the apartheid government.

In an organisational setup dubbed “the M-Plan”, each member was required to recruit four persons into a cell and ensure that their identity was not exposed to others, meaning in higher echelons.

In 1962, at the age of 20, I enrolled at the University of Fort Hare and was immediately invited to join the “high command”. Its role was, among others, to recruit students into the reconstituted ANC, direct and supervise their covert work, and organise student meetings with members of other affiliations.

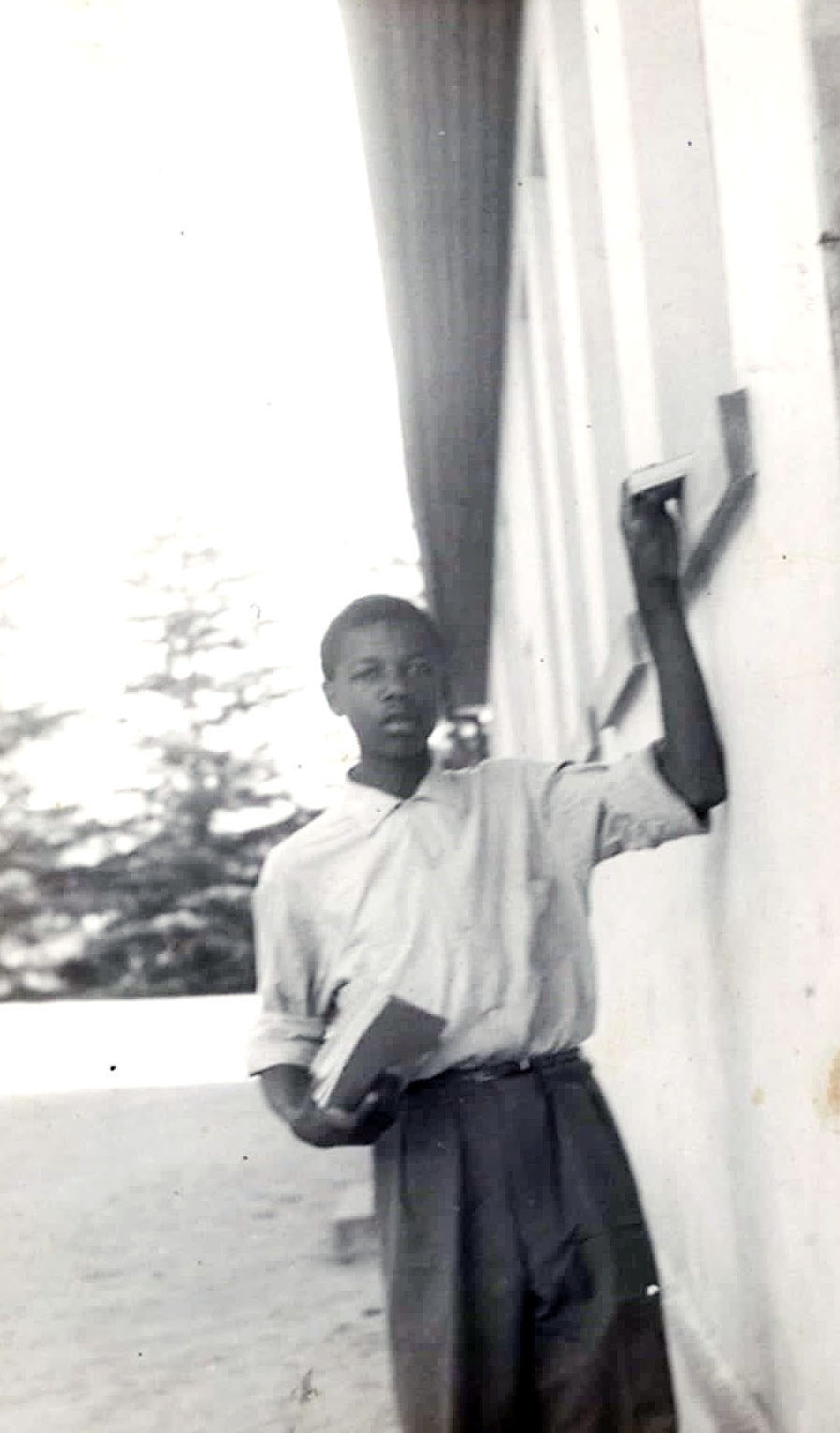

Mavuso Msimang at Inkamana High School with a close friend, Themba Mqilingwa, from Everton, Gauteng. (Photo: Supplied)

In the crosshairs at Fort Hare

My time at Fort Hare was brief.

In May 1963, I was among six students whom the ANC leadership advised should leave the country and continue their studies abroad. I was in the crosshairs of the security police and it was feared my arrest might be imminent. Our group left Fort Hare discreetly, driving the 100km to the small Eastern Cape village of Cookhouse, where we boarded a train to Johannesburg.

We disembarked at Park Station around noon, and started walking towards a menacing cordon of policemen who were randomly demanding to see our dompases, the apartheid regime’s tool for controlling the movement of Africans 16 years and older.

By sheer chance, I escaped the dragnet. Had I not, I would have been promptly arrested and taken to the nearest police station where my dompas would have been stamped “Endorsed Out of Johannesburg”. A policeman would have been detailed to escort me back to Alice, to be charged with leaving the magisterial district without the authorisation of the Department of Bantu Administration and Development.

Mavuso Msimang in his matric year at Inkamana High School in Vryheid, KZN, in 1960. (Photo: Supplied)

Mavuso Msimang, (Right), with a friend on the train traveling to Fort Hare University, Eastern Cape in 1962. (Photo: Supplied)

Safe houses

From Park Station we were driven to Soweto township, southwest of Johannesburg, and placed in different safe houses. I was paired with Gideon Vakala, who had recently been acquitted in a sabotage case in Alice, and placed with a family in Orlando East.

Two days after our arrival, two policemen came to arrest the activist owner of the house. On seeing them walk round the house, we quickly exited, jumped over five fences and hid in the outside toilet of the fifth house.

I phoned Paul Rangongo, a fellow high command member, and told him about our predicament. He arranged for me to stay at his brother’s house in Mndeni in Soweto. Vakala was accommodated elsewhere.

Sitting with mom in her bedroom in Pretoria in 1995. (Photo: Supplied)

Final lap

The final lap of our journey to exile began six weeks after we left Fort Hare. We joined a group of MK recruits and travelled together by train to Zeerust, in the then Transvaal province (now North West), where we arrived in the evening. A guide whisked us out of the railway precinct and led us on bush paths towards the Botswana border.

Taking cover behind a tree grove barely 100m from the border fence, we waited for a South African army patrol vehicle to pass, its headlight beams illuminating the road ahead.

At a signal, the group darted across the road, pulling tree branches to cover our tracks. We jumped over the fence to enter Botswana and spent the night in Lobatse in south-eastern Botswana. The following evening we took a train to Francistown, the second largest city in the country.

A White House stay

In Francistown, we stayed in a refugee house generously provided by the Botswana Council of Churches. Presumptuously called the White House, it accommodated refugees, mostly from South Africa, but also from Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and Namibia (then South West Africa).

Speaking of which, one afternoon we welcomed four exhausted youths from that country, who had walked and hitchhiked across the Kalahari Desert to get to the centre. Among them was a scraggy lad named Hage Geingob. He is now the president of Namibia.

The three-month sojourn in Francistown was a very testing time. For months, the 30-odd MK recruits and 12 students living in the White House waited for an aeroplane to take them to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, where their final destinations would be finalised.

It felt like eternity. We bided our time reading and playing cards, draughts, Monopoly and morabaraba, the traditional African game associated with problem solving. We visited a nearby village for the local brew, and improved our Setswana by chatting up the ladies.

Taken during the funeral of James Stewart, in January 2016. Front row (from left) General Teddington Nqapayi, Joel Klaas Ngalo and Mavuso Msimang. Back row (from left) Dr Bongiwe Njobe, Nosizwe Nokwe, Thoy Tshabalala. (Photo: Supplied)

Devastating raid news

On the afternoon of 11 July 1963, a South African radio station broadcasted the devastating news that the police had raided the secret headquarters of the top ANC, MK and Communist Party leaders in Rivonia outside Johannesburg. Gleefully, the announcer said that Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, Lionel Bernstein and Bob Hepple had been arrested.

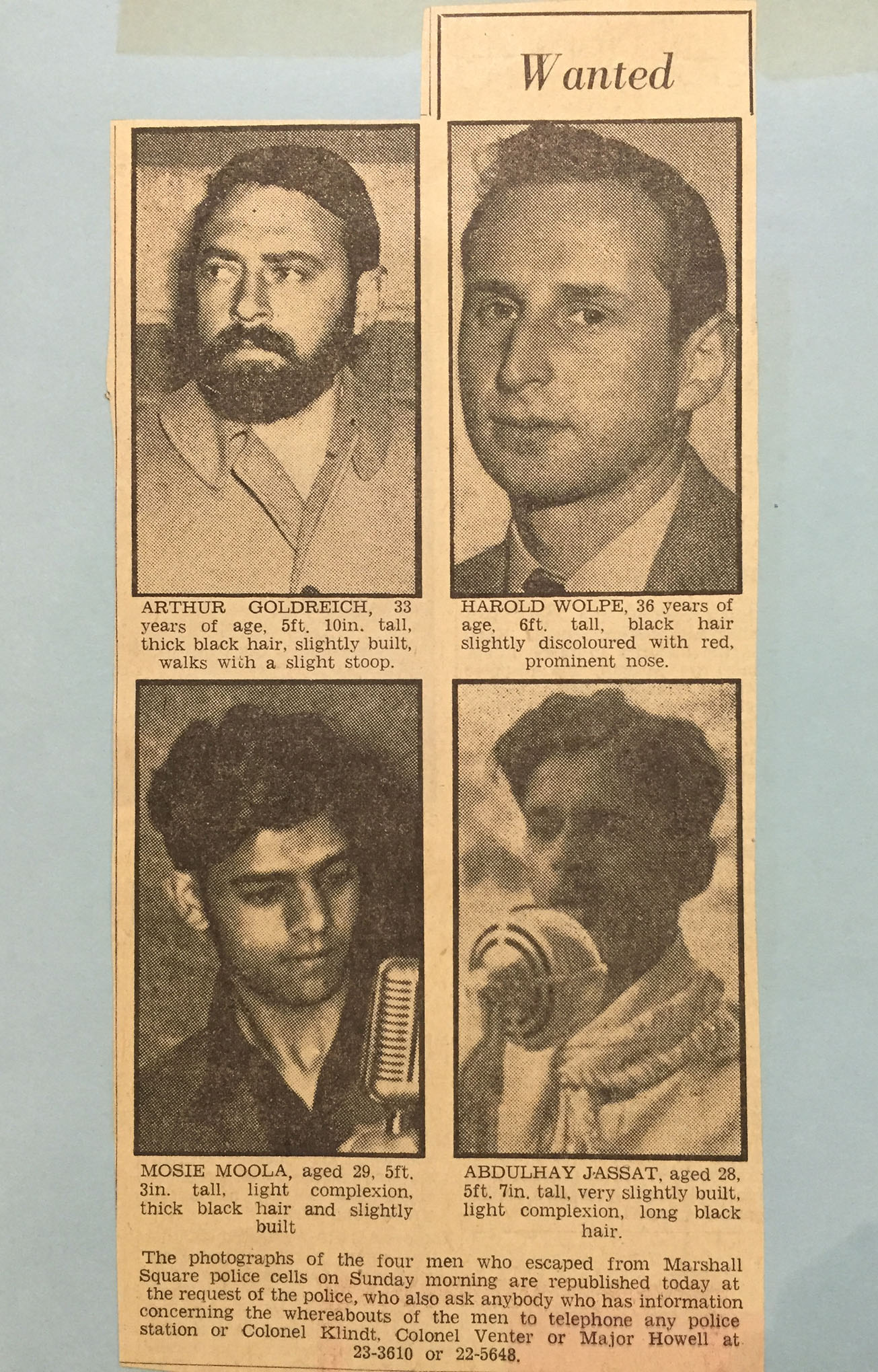

Continuing, the broadcast said the police had found a memorandum of “Operation Mayibuye” that outlined a guerrilla warfare strategy, as well as documents on manufacturing explosives. A day or so later, we learnt that Arthur Goldreich, Andrew Mlangeni, James Kantor, Denis Goldberg, Harold Wolpe and Elias Motsoaledi had also been arrested. The state, I said to myself, had sufficient evidence to send our leaders to the gallows for treason.

The prospect of spending years in an academic institution while apartheid was intensifying its brutality unsettled me. Surely MK needed all hands on deck. I came to the conclusion that what I needed to study was how to best defend my people in the face of escalating state brutality.

My mind was made up. I approached Tat’u Ngcapepe, an MK leader I had befriended, and asked him to tell the ANC leaders about my fervent wish to undergo military training.

The police were hoping for information and even offered reward money for news about their whereabouts. (Image: Supplied)

Rivonia escape lifts the mood

When the news broke that four Rivonia detainees had escaped from Marshall Square Police Station on 11 August 1963, a month after their arrest, the White House went into raptures. Goldreich had promised a prison warder, Johannes Greeff, money if he could facilitate the escape of himself, Moosie Moolla, Abdulhay Jassat and Harold Wolpe. Years later I was told, in the parlance of the time, that Goldreich could “charm the knickers off a nun”.

In an indescribable manner, the escape of the four bolstered my resolve to get into MK as soon as possible. Adding to the excitement, when our repeatedly cancelled charter finally landed, Vivian Ezra, the “owner” of the Liliesleaf farmhouse, joined our 28-strong group of mainly MK cadres and students on its flight to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania.

My request to join MK was promptly granted, and two weeks after our plane landed in Dar es Salaam, I was on board an Aeroflot flight to Moscow for year-long training in urban guerrilla warfare. Additionally, four of us were selected for training in high-frequency radio communication, using morse code.

Serving on the high command

On returning to Tanzania, I was tasked with setting up the ANC’s technical communications system and leading the team of operators. In 1967, when MK joined forces with the Zimbabwe African People’s Union guerrillas during the 1967 Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns in Zimbabwe, I served on the joint high command.

I attended the landmark 1969 ANC Morogoro Conference as an MK delegate. Appointed secretary to ANC president Oliver Tambo, I found myself in the presence of a remarkable human being. Tambo possessed awesome brain power. His integrity was unimpeachable, his humility and charm unaffected – he was the epitome of leadership.

In 1972 I was afforded the opportunity to resume my abandoned study programme, following which I worked for international non-governmental organisations and a couple of United Nations agencies, all the while carrying out special ANC missions as assigned.

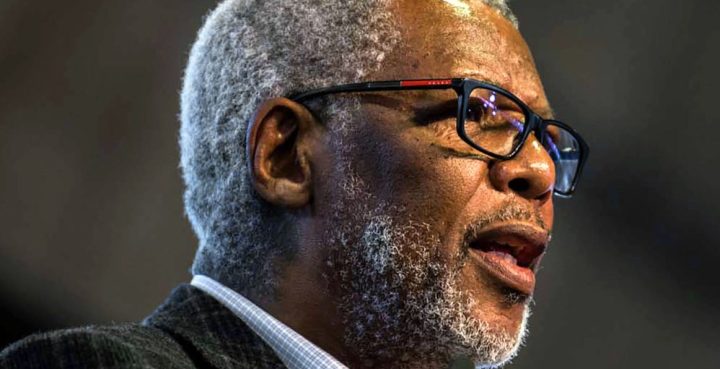

Mavuso Msimang, as Deputy President of the ANC Veterans League, briefing the media at Luthuli House on 31 July 2023 in Johannesburg. (Photo: Gallo Images/OJ Koloti)

Fast forward to Liliesleaf now

In a distressing epilogue, the Liliesleaf Trust, established to manage the nation’s premier heritage site, Liliesleaf Farm, has shut down. In its heyday it hosted an impressive array of national and international visitors with a keen interest in the modern history of South Africa.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Preserving memory and meaning: What Liliesleaf can teach us as a tie to the past, connection to the present and bridge to the future

How does one put this?

Liliesleaf was the secret hideout of ANC freedom fighters and their allies between 1961 and 1963, when they plotted the overthrow of the apartheid government.

It folded in 2020, with the ANC in government.

This is the story of our times. DM

Mavuso Msimang is an MK and ANC veteran.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.