SOUTH AFRICA'S GREAT ESCAPE PART 3

The wife who did not wait — AnnMarie Wolpe: mother, academic, feminist and anti-apartheid co-conspirator

Playwright Anthony Akerman traces the convergences and divergences between his life and that of a formidable woman nearly two decades his senior who sacrificed greatly for her husband’s anti-apartheid activism.

Prison must be like this, I thought as I peered around the dormitory at the dark shapes on sagging coir mattresses. I glanced at the luminous hands on my Delfin wristwatch and waited for the insistent electric rising bell to reverberate around the ivy-clad, redbrick corridors of my boarding school.

Read: Part 1 and Part 2 of South Africa’s Great Escape.

Sunday 11 August 1963 began with a cold shower, shoe polishing, roll call, lumpy porridge, flatulent boiled eggs and Matins at Michaelhouse, in Balgowan in the then Natal Midlands.

During the school chaplain’s soporific sermon, my mind strayed to comforting fantasies of escape. I obviously didn’t realise that that was exactly what four anti-apartheid political detainees had successfully pulled off that morning. Harold Wolpe, Arthur Goldreich, Mosie Moola and Abdulhay Jassat had bribed a young warder called Johan Greeff to help them break out of Marshall Square Police Station’s holding cells in Johannesburg’s CBD.

Something else I couldn’t have known at the time was that 53 years later I would adapt this story as an eight-part radio drama series entitled The Escape from Marshall Square.

Change of plan

On Saturday night the police station had been unexpectedly busy and Greeff wanted to call it off. But Goldreich and Wolpe were adamant their escape should go ahead. They knew if they were tried and convicted they could be hanged. The jailbreak was delayed by over an hour, and when the escapees arrived at the prearranged rendezvous the getaway car was gone.

Fox Street was eerily deserted and they had neither transport nor money. They decided to split up. Moola and Jassat went off in the direction of Fordsburg, Goldreich and Wolpe to Hillbrow.

Arthur Goldreich and Harold Wolpe. (Image: Supplied)

While I was lying in my dormitory bed waiting for the rising bell, Goldreich and Wolpe bumped into a familiar face on Harrow Road (now Joe Slovo Drive) — friend and theatre director Barney Simon, who’d pulled his old Renault over on the side of the road as he’d desperately needed to take a leak.

Simon, although not a member of the South African Communist Party (SACP), was a sympathiser with the cause and always ready to help friends. He took them back to his flat and notified the escape committee. The committee’s members were, among others, Bram Fischer, Hilda Bernstein, Mannie Brown and Ivan Schermbrucker. Most of them were also SACP members. These were the people who were actively involved in helping Goldreich and Wolpe to escape after their prison break.

AnnMarie’s ordeal

Later that morning — as the chaplain strove to instil the precepts of muscular Christianity in 420 terminally bored adolescents — AnnMarie Wolpe, the wife of Harold, was dragged into the headquarters of the Security Branch, the notorious Gray’s Building, where her terrifying ordeal at the hands of the security police was about to begin.

Although she had not been involved in her husband’s revolutionary politics, she had played a role in facilitating the escape and had good reason to fear the consequences — certainly a prison sentence — if they could prove it.

At school we had one or two masters who were members of the multiracial Liberal Party and one of them, Rory Gillespie, was easily persuaded to put a maths lesson on hold and give us a lesson in the iniquities of the apartheid system and how the security police tortured, and sometimes murdered, opponents of the government. I’m sure most of us only found politics marginally more interesting than the Pythagorean theorem, but those lessons left an indelible impression.

Having said that, I don’t recall following the story at the time. Copies of both the British Daily Mirror and the Natal Witness were scattered around the dayroom at school, but headlines about two escaped Communists seemed less enticing to a fourteen-year-old than those that salaciously hinted at the bedroom antics of former topless dancer Christine Keeler, Tory Secretary of State for War John Profumo and — wait for it — the Soviet military attaché, Yevgeny Ivanov.

Front page of ‘The Star, detailing the man hunt, dated 12 August, 1963. (Image: Supplied)

Manhunt

Unbeknown to me, Goldreich and Wolpe became the focus of a massive police manhunt. They’d been detained in the aftermath of the raid on Liliesleaf and the government wanted them to stand trial with other members of the underground leadership arrested on 11 July. A reward of R1,000 — approximately R100,000 today — was placed on each of their heads. However, they successfully evaded the police net and were safely in the UK before the Rivonia Trial commenced.

The Marshall Square escape was one of the last victories opposition forces would have to celebrate for almost a decade. In June 1964, Nelson Mandela and many other leaders of the movement were given harsh prison sentences. Increasingly repressive legislation was enacted, outspoken opponents of the government were banned, placed under house arrest or left the country on exit permits, censorship was pervasive and the press was muzzled.

The repressive clampdown was highly effective and, as a teenager, I grew up in what I later heard described as the Silent Sixties — an era that only ended with the 1973 Durban strikes.

As a student, I loathed BJ Vorster’s police state. On protest marches I sang We Shall Overcome, could quote from Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and even knew about Malcolm X — but, even though I’d worked for a time in the National Union of South African Students office, I’d never heard of Nelson Mandela.

Crash course in Struggle history

Of course, Mandela couldn’t be quoted and neither could his photo be printed in newspapers, but it still amazes me that I can’t recall anyone ever mentioning his name. My education in the history that wasn’t taught in schools alongside the Great Trek began when a friend gave me a copy of Mary Benson’s The Struggle for a Birthright (1966).

By then I’d left the country. In Europe, I interacted with political exiles and received a crash course in Struggle history. That’s when I would have heard about Goldreich and Wolpe and their daring escape.

I thought it had all the makings of a great movie. Two guys fighting for justice outwit a fascist police force, escape to Swaziland (now Eswatini) in the boot of a car and — disguised as Anglican priests — fly over South Africa to Bechuanaland in a Cessna with a dodgy pilot who could easily have put the aircraft down in Pretoria. Why hadn’t Hollywood optioned the story?

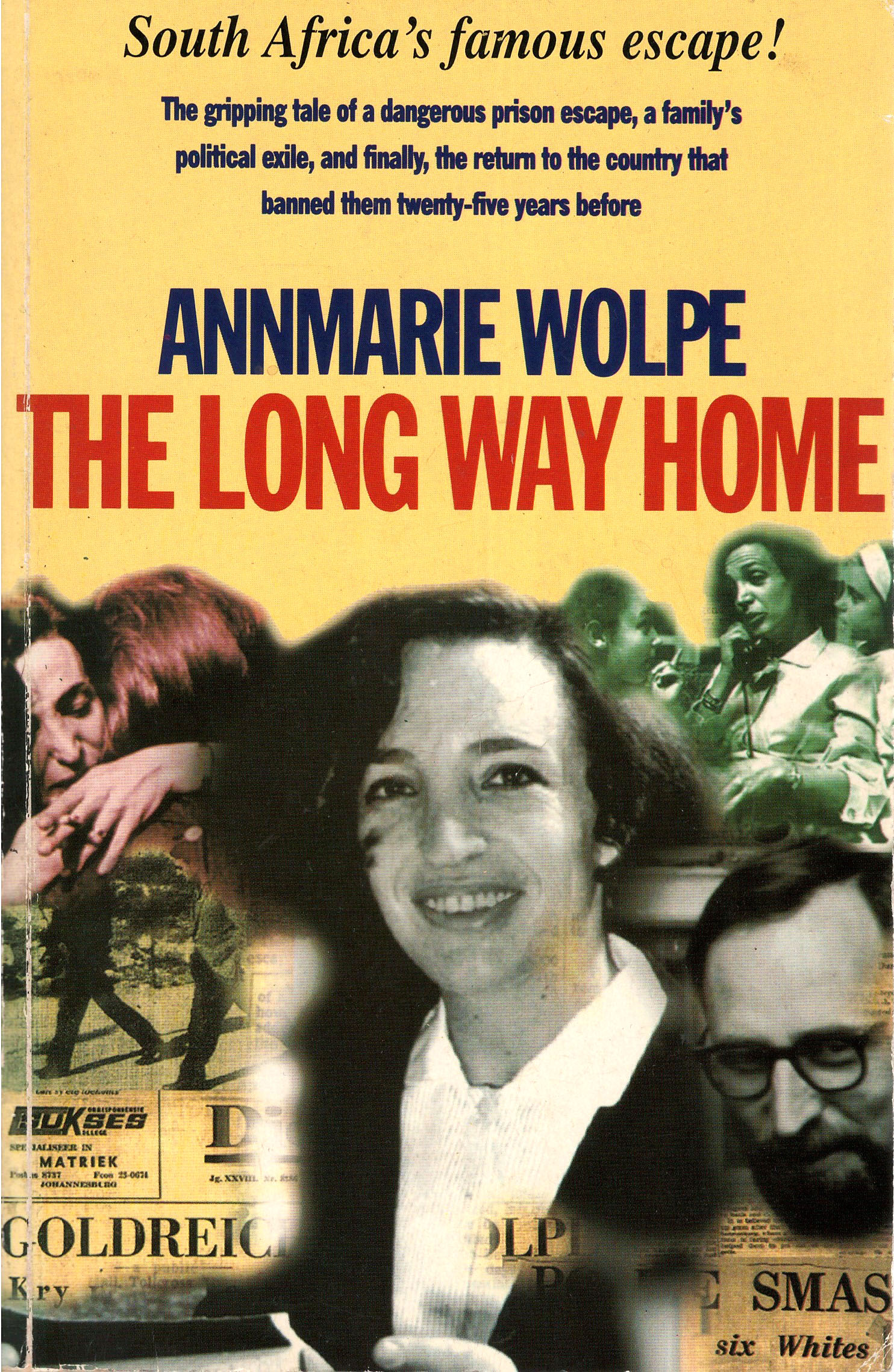

Well, for one thing, the two leads were communists. More problematically, you’d have had to fudge, or leave out, parts of the story to avoid implicating people — such as Barney Simon, for example — who were still living in South Africa. That’s one of the reasons why AnnMarie Wolpe waited until 1994 to publish The Long Way Home.

AnnMarie Wolpe’s ‘The Long Way Home’. (Image: Supplied)

Leaving the children behind

Shortly after Goldreich and Harold Wolpe arrived in the UK in 1963, AnnMarie was reliably informed that her rearrest was imminent. She left the country the following day and had to leave her three children behind — the youngest of whom was baby Nicholas, who’d recently very nearly died. Once the family was reunited, she made a life for herself in England and had a distinguished academic career.

She was a co-founder of the Feminist Review and published, among others, Feminism and Materialism.

Both she (in London) and I (in Amsterdam) had a stiff drink and couldn’t hold back our tears on 2 February 1990 when we realised it was possible for us to go home. I was homesick for South Africa, but wasn’t sure I’d want to live there again.

AnnMarie also had misgivings about uprooting her family for a second time. But she knew that’s what Harold wanted and so in the end she, and at different stages her children, eventually did return. Harold lived to see a democratic South Africa with Mandela as president, but died suddenly days after his 70th birthday in 1996.

Unlike her husband, AnnMarie had never been a member of the SACP, nor had she been involved in any of his underground political activities. In her book, she confesses to being afraid of the police, of fascism, of violence, but she also explained the position of many women who were married to men who were, or became, political activists. “We women did what we had to do, and accepted our husbands’ actions. … Our voices were not heard.”

Tellingly, The Struggle for a Birthright is dedicated “to the wives who wait”.

Keeping the home fires burning

Of course, there were women like Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi, Ruth First and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela who became icons in the fight against apartheid. However, during the 1950s and early 1960s revolutionary politics was predominantly a male preserve. Men of that generation were brought up to believe male and female roles were clearly, if not immutably, defined. Men were in the front line, took the decisions, made the bombs, blew up pylons, left the country to undergo military training. Women kept the home fires burning.

“Hazel (Goldreich) and I agreed we would never be involved,” wrote AnnMarie, “because we would be there to look after the children.” Nonetheless, Hazel was arrested at Liliesleaf and, like her husband, detained at Marshall Square under the 90-Day Act. Harold Wolpe’s involvement inevitably had far-reaching consequences for AnnMarie and her family.

The Long Way Home tells two parallel stories, as AnnMarie and Harold were mostly separated in the weeks following the Liliesleaf raid. The story is narrated in a way that makes it possible for AnnMarie to tell Harold’s story faithfully without losing a female point of view.

Long Way Home reborn for radio

Because I’d read her book several times and had begun work on turning her book into a radio drama, I felt AnnMarie wasn’t a stranger when we met at Liliesleaf in 2016. She was 85, confined to a wheelchair after a recent operation, a stylish dresser and an outspoken and independent thinker. She was less a conformist revolutionary than a nonconformist rebel who questioned all orthodoxies.

She also had a predilection for robust expletives and eyed me narrowly when she said, “I hope you won’t be shocked if I use the word ‘fuck’ a lot”.

We talked about the genesis of her book. She told me friends in Yorkshire had taped extensive interviews with both her and Harold. These were later transcribed and were the notes she worked from when she sat down to write The Long Way Home more than two decades later. Even then, she confided to me, there was a lot she was not allowed to say. “Harold was very controlling,” she added.

Cast prepping for recording with director Julia Ann Malone, SABC Studios 2016. (Photo: Anthony Akerman)

Julia Ann Malone did an excellent job directing The Escape from Marshall Square for the English radio station SAfm. Her casting of Frances Slabolepszy as AnnMarie proved to be inspired. I spoke to AnnMarie after the first episode had been broadcast. She hadn’t had a good day but was pleased with the final result. She said that she’d found it very difficult to relive the experiences of those years.

Frances Slabolepzy performing as AnneMarie Wolpe, SABC in 2016. (Photo: Anthony Akerman)

Reluctant, irreverent heroine

In March 2017, my wife André and I visited AnnMarie at her home in Cape Town. We’d arranged to take her to lunch but her daughters, Peta and Tessa, were concerned that she might not be well enough. But AnnMarie was taken with my suggestion that we have lunch at Kelvin Grove club, especially after I’d told her there’d been a time when Jews weren’t admitted as members.

While I was at boarding school reading the latest revelation in the Christine Keeler scandal and facing no greater danger than being flogged for talking before grace, the reluctant heroine I was having lunch with was a 33-year-old mother of three, had smuggled hacksaw blades into Marshall Square, had worked as an intermediary for the escape committee, had been savagely interrogated by the notorious “Rooi Rus” Swanepoel, had seen her brother James Kantor arrested for no reason other than he was Harold’s brother-in-law, and had had to abandon her children, her country and her life at a day’s notice.

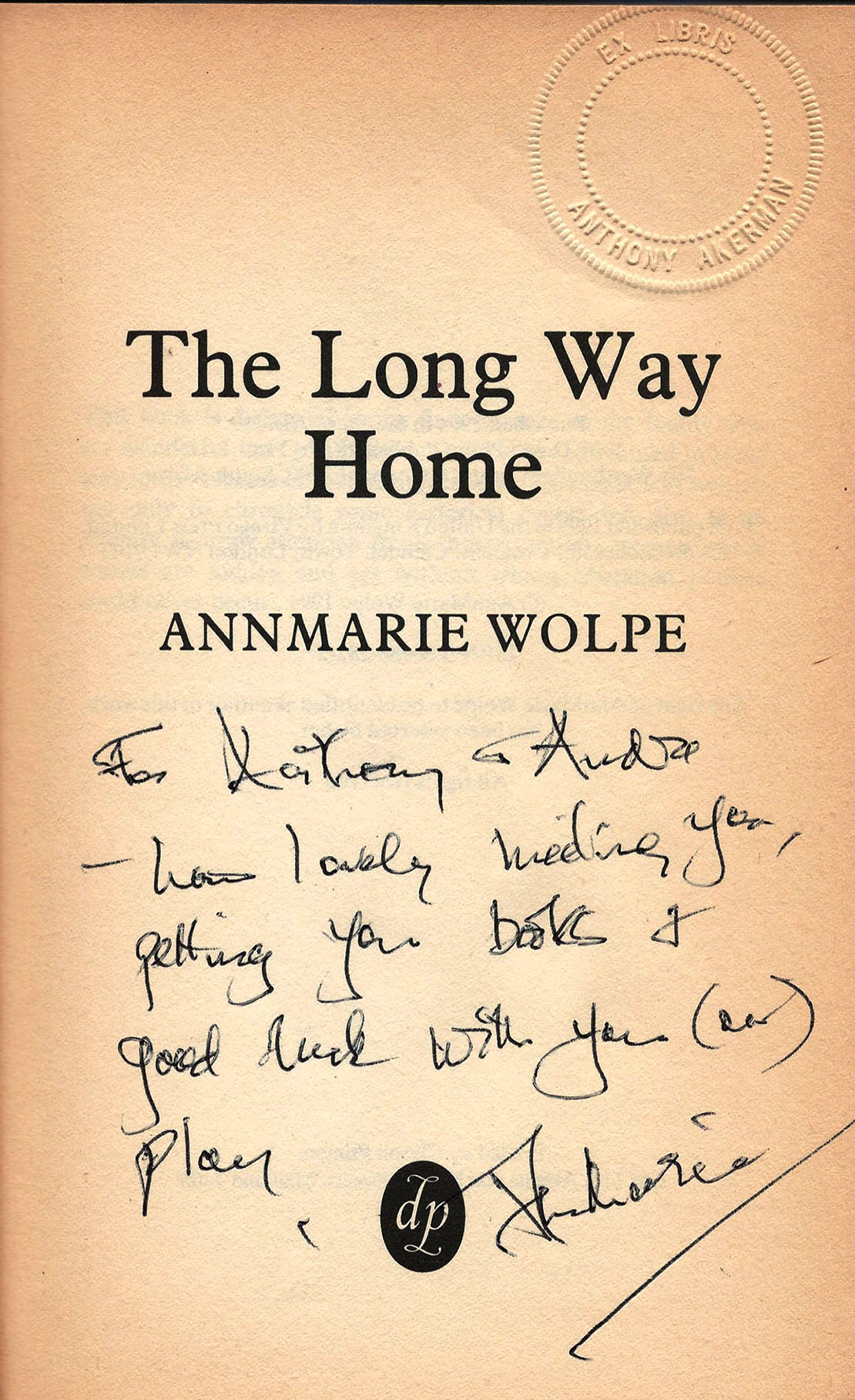

I found her an irresistible combination of elegance, intelligence, poise and irreverence. She’d asked me on several occasions how I’d come across her book — and each time she told me very few people knew about it. Was that true or was she being modest? Perhaps its appearance in 1994 had been eclipsed by the other momentous political events of that year, but I was pleased to hear David Philip Publishers had brought out a new edition to coincide with the radio series.

AnnMarie was in great form and was clearly enjoying trading witticisms with André. But was she laughing too much, becoming too animated, overdoing it?

Mindful of Peta and Tessa’s concerns, I asked whether she was ready to go home. She looked at me as if I’d made an indecent proposal. “Fuck going home,” she said tossing her head back, “pour me another glass of wine”. DM

Inscription to Anthony Akerman and Andre Hattingh. (Image: Supplied)

Anthony Akerman is a playwright who has also written extensively for radio and television. His radio plays include dramatisations of Ruth First’s 117 Days, Mary Benson’s A Far Cry and AnnMarie Wolpe’s The Long Way Home. He has written radio docudramas on the lives of Robert Sobukwe, Nelson Mandela and Bishop Desmond Tutu. His award-winning stage plays include Somewhere on the Border, Dark Outsider, Old Boys and Leading Ladies.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.