SOUTH AFRICA'S GREAT ESCAPE: PART 1

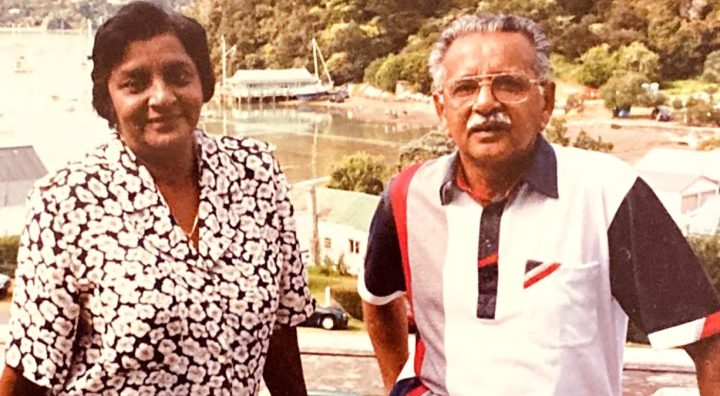

‘The physical and emotional effects of torture have endured my whole life’ Charlie and Harlene Jassat’s story

11 August 2023 marks the 60th anniversary of what is known as the Great Escape. To commemorate one of the most successful jailbreaks in South African history and the many struggle activists who fought for a democratic South Africa, Daily Maverick is publishing a series of articles and reflections by relatives, friends and comrades of those involved.

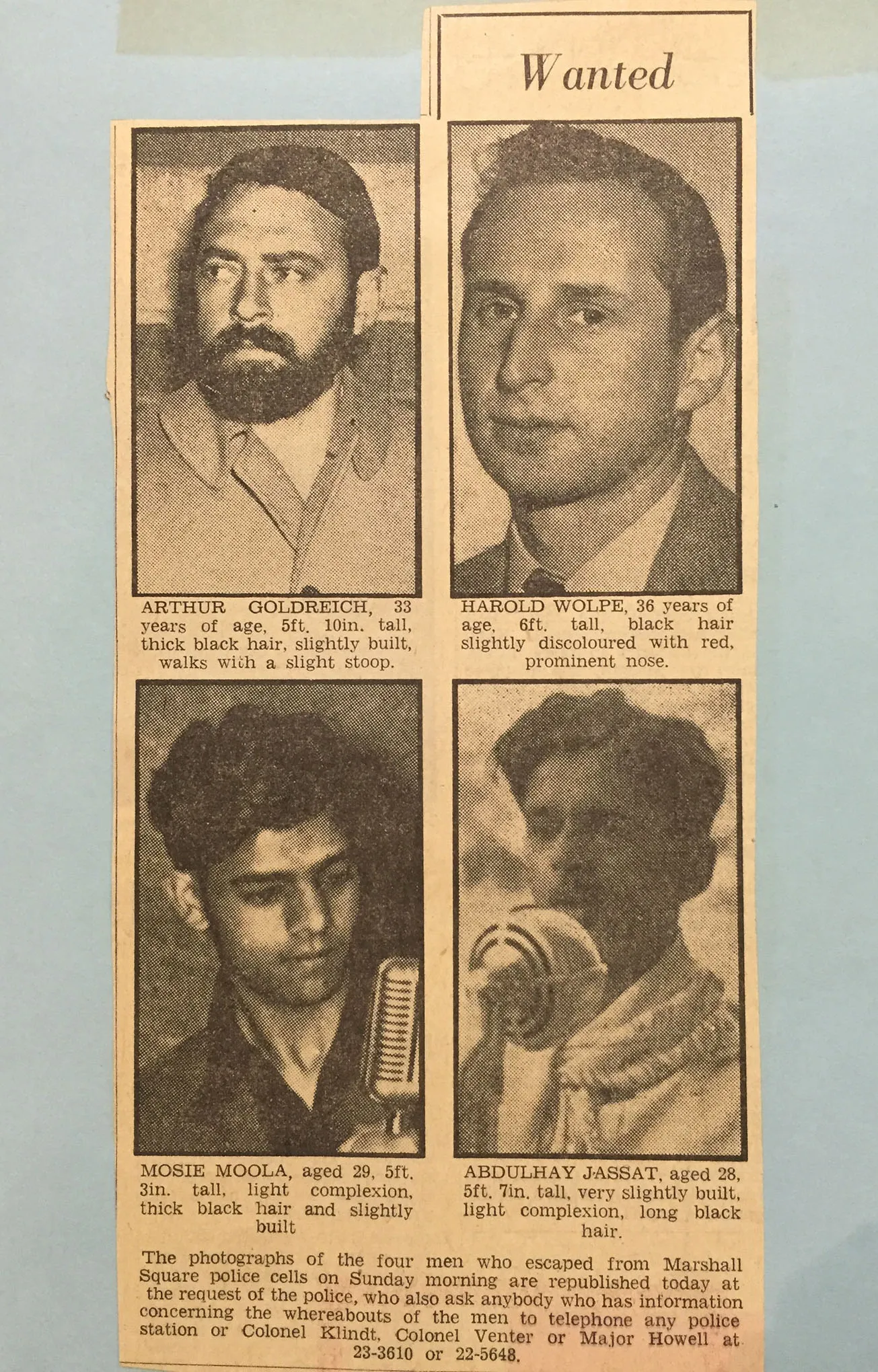

On that day, four freedom fighters — Arthur Goldreich, Abdulhay Jassat, Mosie Moolla and Harold Wolpe — broke out of Johannesburg’s Marshall Square police station. How they escaped and the aftermath is a compelling story measured not only by how they managed to evade the police but also the impact it had on the liberation movement. After the raid and arrest of so many senior struggle leaders at Liliesleaf, which had taken place a month earlier, on 11 July 1963, the escape provided a momentary window of joy and celebration and a morale boost for the movement.

Miraculously all four succeeded in fleeing the country.

These articles, all written by people linked in some way to the struggle, are personal accounts of their or their family’s involvement, and the impact that involvement had on their lives.

*

Abdulhay Jassat is one of the four activists who pulled off a daring escape from the Marshall Square Police Station. His youthful participation in the ANC’s Defiance Campaign and his life of dedication to the struggle for a free South Africa brought him and his wife Harlene scant material reward apart or recognition — only the certainty of being on the right side of history.

I had the privilege of meeting Abdulhay “Charlie” and Harlene Jassat at their home in Killarney, Johannesburg, in July 2023. I had grown up knowing about Abdulhay and Mosie Moolla as the two Indian activists who escaped from Marshall Square Police Station in Johannesburg with my father, Harold Wolpe, and Arthur Goldreich in 1963.

I ask Abdulhay where the name ‘Charlie’ came from, and he tells me that Moolla, with whom he became friends in high school, started calling him Charles of the Ritz because he dressed so well and always cut a dapper figure.

That name eventually became Charlie.

Young activist

Abdulhay tells me about his life of political activism, starting with his early years. He became politically active as 15-year-old teenager.

“I was born in June 1934 in Johannesburg. In 1949 I joined the Transvaal Indian Youth Congress. We participated in the ANC’s Defiance Campaign (non-violent protests against the apartheid regime launched in 1952), in school boycotts and strikes. We protested against the forced removal of citizens from Sophiatown, shouting slogans like ‘We shall not move.’ ”

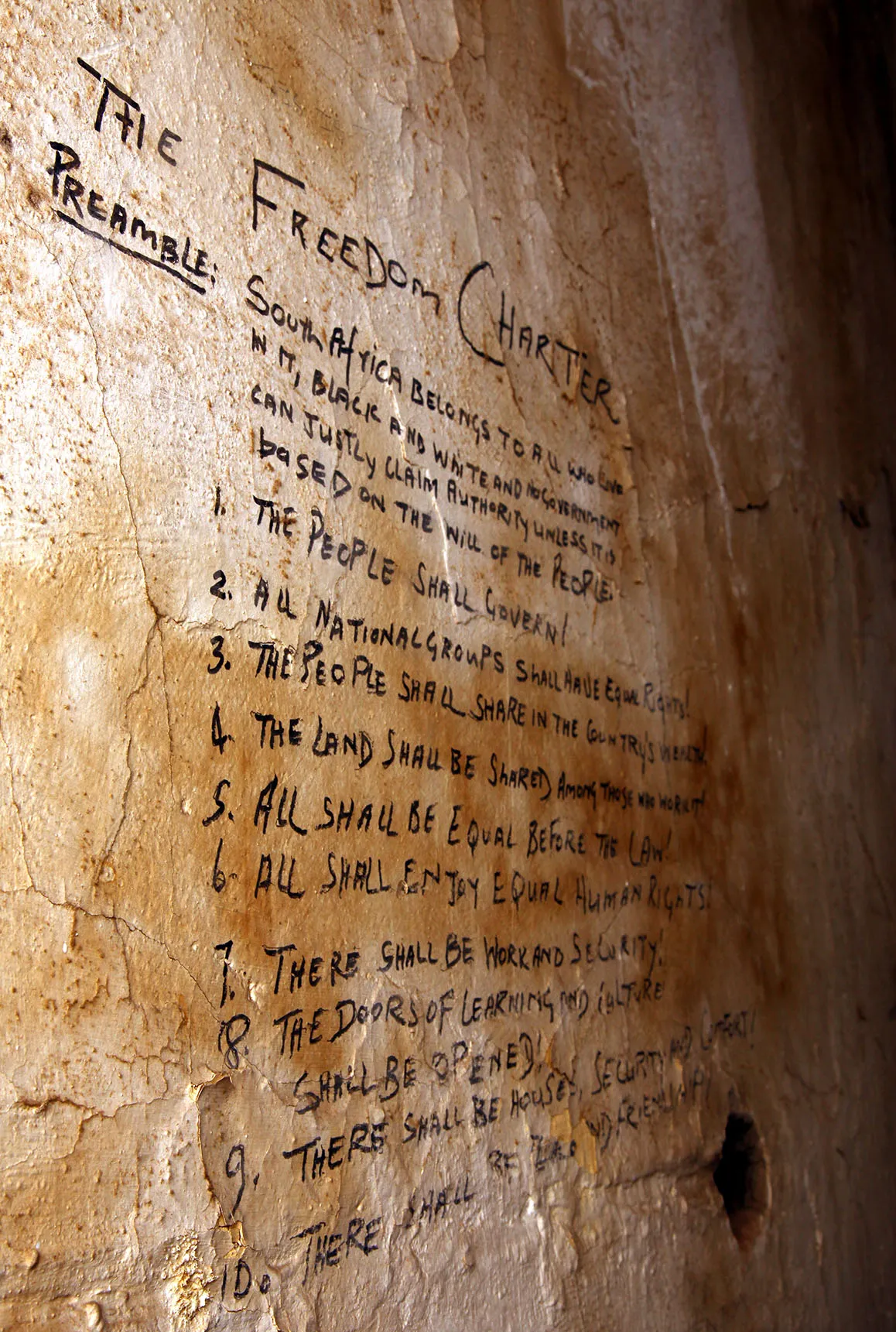

They went from house to house to poll citizens on their demands and wishes as to what a free and democratic South Africa should be like. This was part of a mass campaign across the country and culminated in the famous Congress of the People meeting in Kliptown, which resulted in the drafting of the Freedom Charter.

The earliest known transcript of the “Freedom Charter” written on the wall of the holding cell below Court Room C at the Palace of Justice on 16 February, 2011 in Pretoria, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Economic Development: City of Tshwane / Matthew Willman)

“I was arrested on many occasions for putting up posters, writing slogans and distributing leaflets. We would be taken to court, where we would pay an admission of guilt or a fine, and would then be released. In 1960 that changed. I was arrested during the State of Emergency (declared by the apartheid government on 30 March 1960 after the Sharpeville massacre on 21 March). We were taken to Marshall Square Prison and then to Pretoria Central Prison — altogether we were in detention for about four months.

Spears of the nation

“[By then] I had joined Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed wing of the ANC. I was the head of one of the units. In the 1960s MK’s [sabotage campaign] would target governmental infrastructure such as pylons, post offices and railway command boxes. We were instructed that no lives should be lost and all operations should be executed after 10pm.

“In April 1963 I was again arrested and taken to Marshall Square. I heard screaming down the hall. I was taken to a small cell where I found [fellow activists] Reggie Vandeyar, Indres Naidoo and Shirish Nanabhai, all badly battered and injured. The following day, along with Isu Chiba, we were transported to Johannesburg Park Station, where one by one we were taken into a room for questioning.

“When it was my turn, I was first questioned for half an hour and then they put a wet hessian bag over my head and tied it over my knee. They lay me down on the cement floor, took off my shoes and socks and tied something to both my big toes. They told me that if I did not tell them where our instructions were coming from, they would send electricity though my body, starting at 10 volts for 10 seconds.

“I could not see well through the hessian bag. I could make out images. As the questioning continued so the voltage was increased up to 220 volts. After about 90 minutes they made me stand on the spot while they interrogated me. They wouldn’t let me lean on anything and I wanted to collapse. Then they made me put my thumb on a coin on the ground and circle around it over and over again.

“They dangled me outside a window by my ankles, they beat and kicked me. I didn’t talk and I survived, but the physical and emotional effects of that torture have endured my whole life.

“We were detained under the 90-Day Act (this allowed the police to detain someone suspected of committing a politically motivated crime without a warrant or access to a lawyer for 90 days) and faced charges of sabotage. Many were released after 90 days and then re-detained for another 90-day period immediately after release.

The great escape

“It was at Marshall Square that I met other political detainees. Along with Harold Wolpe, Mosie and Arthur Goldreich, we bribed a guard and managed a successful escape from prison on 11 August 1963. Once out, Mosie and I went to Fordsburg.”

Charlie hid in different homes and on a farm for a while. Eventually, he dressed up as a Muslim woman, wearing a wig and lipstick, and went from Mafeking to the border and crossed into Botswana. The ANC had officially established its Tanzania mission in 1963, with headquarters in Dar es Salaam, and it is there that Abdulhay arrived after a difficult journey of about three months. He needed to be in hiding all the time and was in a state of constant high anxiety.

Harlene had met Charlie in high school through her brother. Although they were not yet in a relationship, they were friends. After Charlie’s arrival in Dar es Salaam word got out that he was not doing well. He was having seizures and needed support. Harlene left her family and friends to be with Charlie and provide the support he needed. This was a hard transition for her, leaving all that was familiar, with little preparation or help for her new life.

She managed to find work as an English teacher. Charlie worked for the ANC, but wasn’t paid a salary.

The police were hoping for information and even offered reward money for news on their whereabouts.

(Image: Supplied)

Women’s invisible labour

Harlene says the women supported their husbands and the ANC, but were relegated to domestic tasks, cooking and running fundraising events. That’s what the women were used for — carers, nurses and caterers.

Charlie’s health was not good. He suffered blackouts and epileptic fits caused by the damage to his nervous system from the electric shock torture. After eight years in Dar es Salaam, they moved to London, where they continued to be active within the ANC until their return to South Africa in 1993.

In the UK, Harlene worked for an insurance company and then the International Defence and Aid Fund, which had been created during the Treason Trial. Charlie continued to work for the ANC, but still didn’t receive a salary. After their return to South Africa they were not offered formal positions, but continued their support of the ANC.

Selfless service

I am struck by these humble people who have dedicated their lives to the struggle against apartheid and who in the new South Africa were somehow left out in the cold. Possibly they were not deemed high-profile enough, or perhaps seen as not active enough, but they have seemingly accepted this without resentment.

I ask them how they feel about all of this today. Their response is that they “did what they did without asking questions” — that is how it was.

Their contributions to the anti-apartheid struggle had enormous impacts on their lives. For Charlie it is physical and psychological, and for Harlene psychological. They both suffered trauma and loss. Perhaps what motivated them during all the years of struggle and exile was the fact that there was a community spirit fostered by comrades working together, joined by a common cause and a common struggle. It came with its own stresses, but also with laughter and support.

They have lost that community and today their lives are quite isolated, apart from the occasional memorial service which, although sad, brings comrades together again. Despite it all, and in spite of their disappointment in the current state of democratic South Africa they sacrificed so much for, they remain the same decent people they always were, filled with kindness and integrity. DM/MC

Peta Wolpe is the daughter of Harold and AnnMarie Wolpe. She works in the climate and energy space, focusing on energy poverty and the Just Transition. Prior to returning to South Africa in 1996 she worked as a senior psychiatric social worker in London.

This article is based on a combination of edited extracts from an interview transcript for the ANC oral history project with Abdulhay in 2006 and an affidavit he signed in 2017, as well as interview with Abdulhay and Harlene on 3 July 2023.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I’d love to say something profound about this, but how to without ‘virtue signalling’..?

Maybe just… “thank you for your service…”