STUMBLING BLOC

BRICS lacks cohesion and coherence, and SA should focus on its real interests

International associations, alliances and groups have always been around. But BRICS, without real internal cohesion or fundamental guiding principles, seems more like building bricks without straw than the creation of a major international presence. South Africa should recalibrate its international efforts to pay more attention to its real interests.

That nations seek to align with other nations is a defining characteristic rather than an unusual pattern in international relations. Here, we are contemplating the curious circumstances of BRICS. But well before that formation came into existence, this impulse reached back to the earliest identifiable versions of international life.

Early historical writings speak of kings and pharaohs marrying off their children as a tool to create or cement an alliance or treaty — a pattern that extended well into more modern times. Similarly, international relations textbooks often point to the systems that evolved in places like early China where the smaller kingdoms developed alliances to carry out trade — or wars of conquest.

Nations (or perhaps, more accurately, often their leaders) have always sought out others who can help them advance their objectives in the international arena, or defend against others seeking to achieve such changes against them. Alliances and cooperative arrangements can either be (economically, politically or militarily) stabilising — or profoundly destabilising. Or both.

Consider such examples as the pre-World War 1 European alliances, the European Economic Community (now the European Union), the Non-aligned Movement, Nato (and thus the Warsaw Pact as well), Asean, and, of course, the League of Nations and the UN.

The ‘Concert of Europe’

After Napoleon’s conclusive defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the Congress of Vienna blessed “the Concert of Europe”, a loose association of the leading conservative states of that continent — Prussia, Austria, Russia and France, with Britain standing somewhat aloof, but supportive of the idea. The plan was that this ensemble would help to keep interstate conflicts under control (or, later, channel competition elsewhere away from Europe) and preserve rule by the conservative elites of all of the other states on the continent.

The system began to break down at the end of the 19th century with the signing of the Russian-French Entente and the Triple Alliance comprising a powerful, now-unified Germany, Austro-Hungary and a newly united Italy. Britain kept out of the new alliance system until the early 20th century as it slowly shifted towards a friendly understanding with the Entente and the firm enunciation of a policy that it would oppose militarily an invasion of the neutral buffer state of Belgium.

In 1914, Germany’s invasion of France through Belgium drew Britain into the emerging general conflict that had erupted from the assassination of the heir to the Habsburg throne, and the conflict became the First World War. After the war ended with a German defeat, the victors established the League of Nations to prevent future outbreaks of such devastation. Sadly, the league had neither the will nor the power to stop smaller aggressions such as Germany’s remilitarisation of the Rhine territories, its annexation of Austria and dismemberment of Czechoslovakia; the Italian conquests of Albania and Abyssinia; and, finally, Japan’s invasion and conquest of major parts of China.

By 1939, Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland as the next step in re-establishing a revanchist primacy in Europe triggered declarations of war by the UK and France against Germany, in line with their alliance with a now-beleaguered Poland. Meanwhile, the new German-Soviet Pact effectively guaranteed Germany an early victory in the East until its 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. That, together with the Japanese attack on US naval forces in Hawaii at the end of that year, collectively brought Britain, the US and the Soviet Union into an uneasy but militarily successful alliance that defeated Germany and Japan and led to the creation of the United Nations.

The UN, EU and Nato

While the UN has many critics for its inability to prevent conflicts of varying intensity and extent from occurring, nevertheless, it has been more successful in bringing some of these to an end, in carrying out a vast range of other important global functions through its specialised agencies, and in providing a forum for the airing and debating of international grievances. What it has been unable to achieve is to prevent one of its Security Council members from engaging in warfare if they have chosen to do so, as with the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, the earlier US military campaigns across the entirety of Indochina, or Chinese repression of Tibet.

By contrast, the European Union (and its predecessor, the European Economic Community) was built upon the impulse to make Western Europe’s economies act more in synchronicity — and with the implicit hope that such economic harmony would, eventually, evolve into a greater political unity of purpose. With the exception of Britain’s departure from the EU several years ago, the grouping has continued to add members since its establishment. Several additional nations, including Turkey, Georgia and Ukraine, are eager to join as well.

A key for membership is adherence to economic policies that allow new members to act in conjunction with those which are already members. Some, but not all, members are also members of the European Central Bank, which further enforces common economic and financial policies, such as the issuance of the euro as a common currency. Throughout its history, reaching back to the late 1950s, formal political (or defence and security) unification has not really been on the EU’s agenda.

Formal Western security cooperation as part of the Cold War began in earnest after the Soviet Union-inspired coup in Czechoslovakia in 1948, leading to the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, Nato. Military pressure from the East was a strong goad. The principle of mutual defence was articulated in Article 5 of its charter, stating as doctrine that an attack on one member would be considered an attack on all.

In the succeeding years, the alliance continued to gain new members, most especially from among former Soviet satellite states and some former Soviet constituent republics, all of which were eager to join once they were freed from Moscow’s control. While the alliance presupposed it was a grouping of democratic states, security trumped democratic values as the alliance included states like Portugal, then ruled by a dictator, on geopolitical grounds, and other states such as France, Belgium and Britain which, at the time of joining Nato, still ruled large colonial realms.

Meanwhile, Nato’s antonym, the Warsaw Pact, had brought together Eastern European states and the Soviet Union in an ostensibly defensive alignment. Crucially, however, the pact never managed to realistically create an organic rationale for its purpose or even its existence, and so it quickly expired once the Soviet Union disintegrated. Eventually, too, the Soviet Union even acquiesced in the reunification of Germany as a Nato member.

Asean and the Non-Aligned Movement

In East Asia, as the US’s Vietnam War was drawing to an end, Southeast Asian nations — from Indonesia to the Philippines — came together to form the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or Asean. The inspiration for the body was to move beyond a divisive international relations climate in the region, to bring its members into greater policy harmony, and to achieve this without being in direct alliances with larger powers. Over the years, it has gained a number of new members such as the three states of Indochina and Myanmar, although it has not yet achieved the kind of policy unanimity seen in the EU or Nato (and some of these members are anything but democratically governed states).

In the meantime, however, the increasingly challenging security climate in East and Southeast Asia, with a growing competition between the US and China, has given birth to two tacit, semi-alliances — Aukus and the Quadrilateral. The former brings together Australia, Britain and the US, while the latter comprises India, Japan, the US and Australia. While neither body has a formal command structure yet, beyond regular consultations; taken together, the partners are increasingly bound together through shared interests in responding to an increasingly assertive China and the new security climate.

Finally, as part of this brief survey, consider the trajectory of the Non-Aligned Movement, the NAM. In the early 1950s, the Cold War seemed to be locking the globe into two camps, a US-centred West or “First World” versus a “Second World” led by the Soviet Union. Leaders from India, Yugoslavia, Indonesia, Burma and China called for a gathering that would represent those nations that were not part of the other two blocs, and which wished to establish an international presence not aligned to either of the two antagonistic camps.

That 1955 meeting, officially the Asian-African Conference, took place in the Indonesian mountain city of Bandung, marking the formal launch of an idea that was supposed to represent more than simple neutrality. (This writer once visited the hotel in Bandung where the conferees had met, and he can testify that 20 years after that conference, the hotel had barely been changed at all in its look and furnishings from a time even before the conference, making it a kind of a monument to “art deco meets tropical splendour decor” from the Dutch colonial era.) The Non-Aligned Movement was formally proclaimed at its subsequent Belgrade meeting in 1961.

While the Cold War was at its height, the leading members of the NAM could assume they were speaking with some degree of moral force on behalf of humanity, even if they were never able to exert sufficient influence to end a war or settle an international dispute — even among the movement’s own members. In truth, this was because the NAM never spoke with one voice, and many of the nations included in it had their own international disputes and conflicts, as well as domestic insurgencies and civil wars. One would be hard-pressed to find any issue now where the NAM as an ensemble has even expressed an opinion.

As a side note, we could also add that Opec (the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) has exerted real power in managing the cost of petroleum and, in at least one case, placing real restrictions on the sale of its product for a specific political purpose. (Of course, it may lose power as the globe shifts increasingly to electric vehicles.)

The origin of BRICS

And that brings us to BRICS and its complications and confusions — as well as how South Africa has positioned itself within that grouping. It is important to remember that BRICS did not arise spontaneously from among its current members.

Despite its implicit positioning as a gathering that stands against the presumed control of global affairs by the West generally, or by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s limited membership, or by Nato, or by the EU and its close partners, the irony is that the very idea of BRICS first arose in the mind of a Goldman Sachs banker, Jim O’Neill, then a glorified sovereign debt bond salesman, back in 2001. The acronym of BRIC may have helped it catch on, even more than the ideas behind it.

Read more in Daily Maverick: O’Neill: South Africa’s inclusion in BRICS smacks of politics

It was O’Neill’s brainstorm that the economic growth trajectories of four emerging-market nations — Russia, China, India and Brazil — made his flogging their sovereign debt bonds — presumably as a kind of package deal — a good investment call, particularly appropriate for fund managers who wanted to score big for their investors. (For what it’s worth, back then, a growing number of retirement and savings growth funds were also targeting the sovereign debt bonds of emerging markets as the next really big thing — including one fund this writer used to grow his meagre savings sufficiently to build up a nest egg to make a down payment on a house.)

As the image caught on, the BRIC collective was increasingly positioning itself as the counter to the rich nations, one that represented a cohort of new, rising nations that could bring to bear the heft of their collective populations, their respective growth rates, and their growing share of global energy and commodity markets — and, in the case of China, a growing share of the production of consumer and industrial goods. Together, this constellation would be “the New World Order,” for real. In time, South Africa courted and begged sufficiently that, especially with China as its sponsor, it was admitted to this gathering, effectively arguing that it represented all of Africa.

The central irony, of course, is that BRICS was actually largely dependent on global economic trends and an insatiable demand for some of its products by the rest of the world — and especially those old, status quo, rich nations.

China’s model of economic growth depended largely on attracting foreign investment to set up plants or partner with local figures to produce (cheaply or cost-effectively, depending on your view) manufactured goods sought by the rest of the world, thereby becoming the latest global workshop. This became increasingly important once China joined the World Trade Organization and acquiesced to its rules and dispute settlement regimens.

Meanwhile, Russia, while it makes very little the world takes besides weapons, rode the growing demand for petroleum and natural gas (which it has in major abundance), and a few other minerals, to fuel its economic prospects. Western and Eastern Europe both became huge markets for these fuel products sent westward to consumers.

India, meanwhile, began to rise with its increasing presence as an IT development site, the location for many financial service firms’ back offices, and other activities that made use of its large and growing number of well-educated English speakers.

Brazil increasingly soared on the back of a vast, efficient agricultural output of such commodities as soya, sugar, grain and poultry, as well as mining outputs, for which global demand rose amid the global commodity supercycle.

South Africa, however, while it gave support to this talk about BRICS’ New World Order, has continued to depend largely on the major markets of North America and Europe for its trade. Yes, China is its single largest trade partner, but, significantly, it is running a trade surplus with South Africa and its imports from this African nation are largely raw commodities, while it sends a wide spread of manufactured goods to consumers here. (But, does anyone truly believe that membership in BRICS has much to do with this China trade? Or, put another way, if South Africa were not part of the grouping, would its China trade have been much less than it is now?)

In fact, while this may be a cynical view, our argument is that BRICS is serving largely as a vehicle for China’s global financial and economic ambitions. Its economy is still so much bigger than the rest of the group’s membership that its chosen policies are almost certain to weigh much more heavily than the views of its ostensible partners.

If by some alchemy, the Chinese renminbi/yuan were to become the de facto grouping’s common currency (despite the fact that at present the dollar largely continues to serve as a global reserve and settlement currency even among BRICS members), this would mean South Africa’s economic fortunes would be tied to a currency whose foreign exchange rate was largely controlled by some Chinese monetary authority committee, and that the terms of trade would be forced to follow such decisions, rather than subject to the expectations of international markets.

Meanwhile, as for its international lending policies, South Africa might want to inquire of Sri Lanka, Zambia, several Latin American nations, and a few others about how things have gone whenever they have tried to negotiate changes in the terms of the borrowing, in comparison, say, to negotiations with international financial institutions or even foreign banks.

Further, from the kinds of international conversations South Africa takes part in, it seems that far too much of its foreign policy apparatus and brainpower is tied up with thoughts of BRICS as the prime vehicle for its international aspirations, rather than some fairly desperate circumstances in several African nations, much closer to home.

Too little energy — or appreciation — seems dedicated to shoring up or deepening relations with this country’s major trade partners (besides China) and with countries where there are still more and deeper interactions by its citizens — putting aside from events directly organised by the government, or those expressions of comradely nostalgia for the good old days of the Soviet Union’s support of a liberation movement.

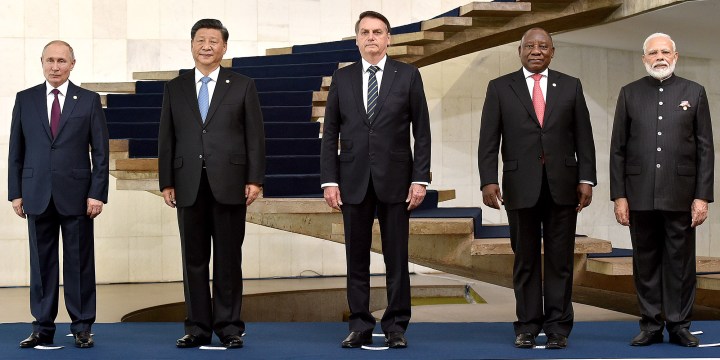

Yes, the decision for Russian President Vladimir Putin to stay at home and participate in the upcoming BRICS leaders meeting virtually, in deference to South Africa’s dilemma over its commitments to the International Criminal Court, can be read as a significant win for the home team.

But it is just as likely the primary concern for Putin was all those uncertainties about just how certain his rule over a state enmeshed in a devastating, embarrassing invasion was, especially in the wake of the Wagner Group’s shambolic march on Moscow. Authoritarians throughout history have rarely found it a good plan to vacate their seat of authority in exchange for a multiday photo opportunity, far away from home.

BRICS without straw

In sum, an alliance or international grouping has worked best when it has a real opponent or a well-articulated set of goals and missions. It is most effective when it has an active, full-time secretariat, and its members are collectively invested in the organisation’s expressed goals. Adding more members — as the BRICS grouping seems intent on doing — will just make group cohesion that much more difficult to achieve.

At this point, though, it remains difficult to identify those conditions for the BRICS grouping, beyond its usual run of communiques following all the meetings, and the modest (at least in international metrics) New Development Bank that is lending back to its members the money they invested in it in the first place.

Read more in Daily Maverick: BRICS countries show signs of division over potential for expanding membership

Beyond all the anodyne nods to amity, development, new paradigms, deeper cooperation and the rest, this time around, the group’s final communiques will have to dance around Russia’s war in Ukraine (unless they choose to blame the whole sorry mess on the West somehow), and express BRICS’ support for a peaceful world.

Perhaps they will just borrow the famous answer from the contestants in the film Miss Congeniality, each of whom said in response to questioning, that without a doubt, their fondest wish was for global peace, rather than something more substantial, substantive and useful for the present world and its troubles. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

“After the war ended with a German defeat, the victors established the League of Nations to prevent future outbreaks of such devastation.”

On a serious point of information, you neglected to comment on the fact that the ridiculous reparations decided at Versailles – and fervently opposed by Jan Smuts – are seen as the reason for Hitler being able to take over a destroyed German nation and go to war again. Much like Verwoerd was able to take the Nats into power thanks to the disgraceful actions of the English army in the concentration camps and the scorched earth policy, and creating apartheid through his bible’s ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ nonsense,