Last week Britain’s prime minister Boris Johnson toured a sparkling aircraft factory in the north of England, elbow bumping its young and diverse apprentices to highlight his investment in a futuristic fighter jet for UK forces.

Johnson said staff at the BAE Systems site in Warton, Lancashire, were “helping make our country safe” and forging Britain as “a science superpower”.

Although his trip to Warton was widely reported, no British journalist mentioned the factory’s role in building a Thatcher-era aircraft which Saudi Arabia still uses to bomb Yemen, its southern neighbour.

That conflict in the Middle East, which started in 2015, has created the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Much of Yemen’s infrastructure has been destroyed and millions of people, including children, are on the brink of starvation.

Saudi Arabia’s air force, together with its allies like the United Arab Emirates, has fueled the suffering by launching tens of thousands of air raids, killing nearly 9,000 civilians and hitting farms over 700 times.

Despite this formidable airpower, their enemy – the brutally effective Houthi rebel group – remains undefeated. It uses Iranian-supplied drones and ballistic missiles, together with Yemen’s rugged mountainous terrain, to compensate for the lack of its own fighter jets, and is increasingly targeting Saudi Arabia.

And the longer the war lasts, the more arms corporation BAE profits, selling at least £15-billion worth of equipment and support to the Saudi military during the conflict so far.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/Declassified-SaudiTornado-inset-1.jpg)

Around 40% of Saudi combat planes have been made by BAE at sites such as Warton, including up to 81 Tornado and 72 Typhoon jets. The rest come from America.

As well as selling the aircraft to the Saudis, BAE promised to help maintain them even in times of war – a vital role as spare parts for these complex aircraft cannot be bought from other countries like Russia or China.

To that end, almost every week a cargo plane flies from BAE’s private runway at Warton to a military airbase in Saudi Arabia, to “provide logistics support for UK-supplied aircraft”, according to defence minister James Heappey.

During the journey, the cargo plane stops at a Royal Air Force (RAF) base in Cyprus, “for the wellbeing of the crew, to refuel and to assure the security of the aircraft and its cargo”.

While in Cyprus, the plane is inspected by British customs officials, who have refused to tell Declassified exactly what is on board, citing a loophole in the UK’s freedom of information act which exempts overseas territories from transparency.

Spare parts

However, by making requests to other government departments, we have some indication of what might be on this cargo flight, and have reason to believe it could include the Tornado spares.

The Ministry of Defence (MOD) told us it sold thousands of surplus spare parts from its own Tornado fleet, which was retired in 2019. One government document suggested 2,323 Tornado spares were sold to Saudi Arabia that year alone.

When asked for more detail, the MOD told Declassified a slightly different story, saying “2,295 lines items of surplus Tornado spares stock have been released to BAE Systems to satisfy the spares and repair requirements of the RSAF [Royal Saudi Air Force] since March 2015”.

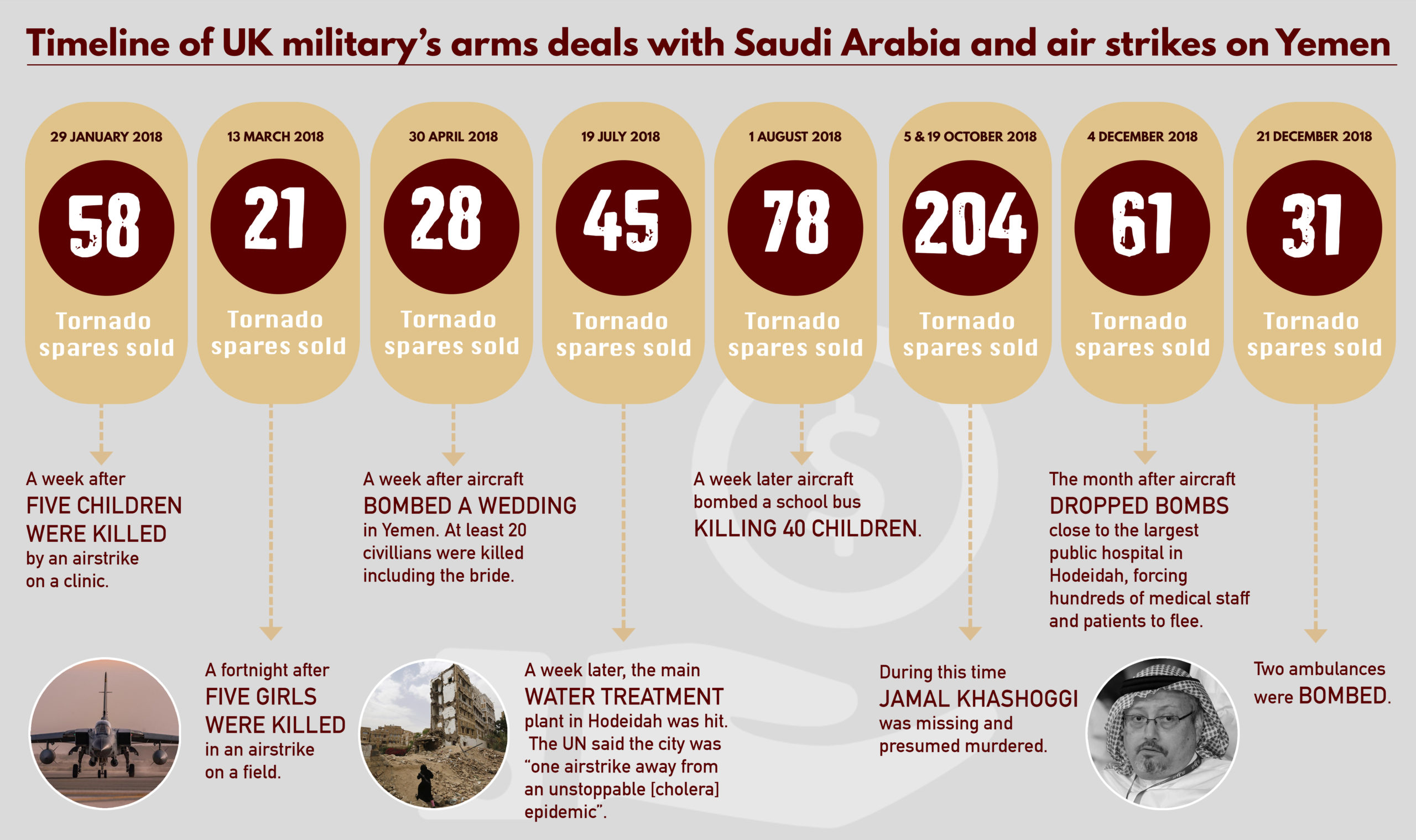

Between 2018 and 2020, the sales took place on average once every 10 weeks in a series of 16 deals, our freedom of information requests have found.

The sales included a bumper deal signed in October 2018, days after Saudi’s crown prince Mohammed Bin Salman allegedly orchestrated the gruesome murder of Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post journalist who had recently criticised the war in Yemen.

Khashoggi was last seen entering the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on 2 October 2018 to obtain documents he needed for his wedding. When he did not emerge from the building later that day, his fiancée Hatice Cengiz raised the alarm, fearing he had been kidnapped. In fact, he was already dead.

Three days later, on 5 October, Britain’s military signed a deal with BAE to sell a record 116 surplus Tornado parts to the Saudi air force. Hours after this deal was signed, Turkish officials said they believed Khashoggi had been killed.

The UK Foreign Office issued statements expressing concern about the journalist’s disappearance, but the military signed another arms deal with Saudi Arabia, for 88 Tornado parts, on 19 October – despite reports emerging that Khashoggi had been hacked to death with a bone saw.

When foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt issued a statement on 21 October acknowledging Khashoggi’s “violent death” for the first time, he said it “had been feared for many days” – suggesting Whitehall officials knew the truth at the time of signing the second arms deal that month.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/Declassified-SaudiTornado-inset-3.jpg)

Yemen

Those arms deals in October 2018 were only a fraction of the Tornado exports over the last three years on which we have obtained data through freedom of information requests to the UK government.

The Department for International Trade said the deals were approved in late 2017 under an “open individual export licence” – a system which Campaign Against Arms Trade (CAAT) brands as “opaque and secretive”.

The reason for the group’s concern is that this single open licence allows for 80 different types of British military surplus, of unlimited value, to be sold to the Saudis.

Most of the items appear to be Tornado spares such as aircraft engines, cannons, weapon sights, missile launching equipment, fuze setting devices, parachutes, radars and thermal imaging technology, to mention a handful. (You can view the full list by expanding the table below).

We showed the documents to Geoff Currums, a retired RAF squadron leader and former fast-jet flying instructor who has taught some Saudi pilots. He said the records confirm these Tornado spares “are absolutely critical in order to continue operations in Yemen”.

“Most of the items are either aids to servicing or items that need to be replaced and serviced, and they are similar to critical items in any other equivalent aircraft,” he explained.

“If BAE are to continue keeping the Tornado airborne, they will need to find sources for these or manufacture them. Bear in mind that production lines for Tornado-specific equipment are closed, except those owned by BAE, so the ex-RAF stockpile is critical at present.”

Sales under this particular open licence began in January 2018, the same month a Saudi Tornado crashed in Yemen. The sales continued throughout 2018 despite repeated attacks on civilians, which were catalogued by the Yemen Data Project and other human rights groups.

Those records, when combined with our freedom of information responses, paint a disturbing picture of British complicity in scores of war crimes, as the timeline below shows.

By January 2019, a year after this series of Tornado exports, the number of alleged war crimes by the Saudi-led coalition that the MOD was aware of had risen from 336 in March 2018 to 394.

Temporary arms embargo

While these arms sales were ongoing, Saudi Tornados were repeatedly seen flying from the BAE factory in Warton, where three of the fleet were reportedly undergoing testing for upgrades such as a new “Damocles Targeting Pod” before returning to the Middle East in March 2019.

Although it looked like business as usual for the arms industry, the government was coming under increased pressure from lawyers for CAAT, human rights groups and aid organisations, all arguing the sale of weapons to Saudi Arabia was illegal.

Under UK law, arms must not be exported if there is a “clear risk” they might be used in a serious violation of international humanitarian law – such as bombing civilians. In mid-2019, an appeal court in London made a landmark decision. In a shock move, judges ordered the government to stop granting companies any new licences to sell weapons to Saudi Arabia, until ministers reviewed the risk of war crimes.

It was hailed as a victory by activists, but there was a catch. The embargo did not apply to open licences that had already been approved before the ruling.

“The British government continued to use surplus MOD stock to supply the Saudis with Tornado components,” commented Molly Mulready, a former Foreign Office lawyer who had helped defend the Foreign Office at earlier stages of the litigation.

She told Declassified the Tornado exports continued despite the Court of Appeal’s verdict that “the British government had conducted itself irrationally and therefore unlawfully in relation to risk assessments around the supply of arms to Saudi Arabia for use in Yemen.”

Mulready added: “Had the British government stopped that supply, those [Tornado] aircraft may have been grounded, and Yemeni lives may have been spared. But the government maintained that supply, the air strikes continued, and many civilians lost their lives.”

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/Declassified-SaudiTornado-inset-6.jpg)

While this supposed arms embargo was in place between June 2019 and July 2020, the MOD made four more deals to sell Tornado spares to the Saudi air force under the open licence, according to records seen by Declassified.

One such deal, in September 2019, took place two days after the Saudi-led coalition bombed a prison in Yemen, killing 156 people in what was the deadliest airstrike for civilians since the war began. Another deal was signed in April 2020, despite the global coronavirus pandemic.

Meanwhile, the Houthis continued to attack Saudi Arabia and defend their own airspace, bringing down another Tornado with a surface-to-air missile.

In July 2020, international trade secretary Liz Truss decided to resume all arms exports to Saudi Arabia, claiming there was “not a clear risk” of British weapons being used for war crimes.

Eight Yemeni children were killed in airstrikes shortly before and after she made the announcement, with the MOD aware that its allies may have committed 516 war crimes by that stage of the conflict.

As trade officials worked round the clock to clear a backlog of arms export applications, the Tornado spares continued in tandem, with another 51 parts sent on 21 August 2020.

By then, however, discontent was bubbling up in unexpected places. Within days of this 14th arms deal for Tornado spares, a lance corporal in the British army, Ahmed Albatati, was protesting outside the MOD building in London in full military uniform.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/Declassified-SaudiTornado-inset-7.jpeg)

Albatati, who was born in Yemen, blew a whistle every 10 minutes to mark the rate at which children were dying from the conflict. He vowed not to stop his protest as long as arms sales to Saudi Arabia continued.

Although he was quickly arrested and later discharged from the army, Albatiti has continued his activism against the war, now as a civilian.

Since his protest, there have been at least two more sales of Tornado spares, even as the atrocities in Yemen continue. He told Declassified: “To think that our government supplies the equipment and training to commit such horrific war crimes is truly sickening, and it’s the exact reason why I couldn’t live with myself if I had continued serving them.

“Not only did they continue these transactions during Jamal Khashoggi’s murder but even worse, continued after a Saudi air strike hit a school bus killing 40 children in 2018.

“The evidence shows that Britain and Saudi Arabia have the same moral belief and that is for the right price, they are willing to overlook anything.”

A UK government spokesman would not tell Declassified how much money the MOD had earned from selling the Tornado spares. Instead he said: “The UK operates one of the most stringent export control systems in the world.

“The Government takes its export responsibilities seriously and rigorously assesses all export licences in accordance with strict licensing criteria. We will not issue any export licences where doing so would be inconsistent with these criteria.”

A BAE Systems spokesperson told Declassified: “We provide defence equipment, training and support under government-to-government agreements between the UK and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. We comply with all relevant export control laws and regulations in the countries in which we operate and our activities are subject to UK Government approval and oversight.”

The Saudi embassy in London did not respond to a request for comment. DM

Phil Miller is staff reporter at Declassified UK, an investigative journalism organisation that covers the UK’s role in the world.

Follow Declassified on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Sign up to receive Declassified’s monthly newsletter here.

You can become a member and supporter of Declassified by visiting here.

A candlelight vigil for Jamal Khashoggi outside the Saudi Arabia consulate in Istanbul, Turkey. (Photo: Chris McGrath / Getty Images)

A candlelight vigil for Jamal Khashoggi outside the Saudi Arabia consulate in Istanbul, Turkey. (Photo: Chris McGrath / Getty Images)