BOOK EXTRACT

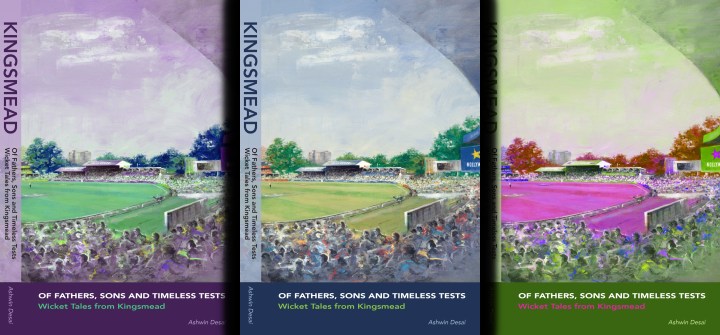

Of Fathers, Sons and Timeless Tests: Wicket Tales from Kingsmead

Kingsmead is like a grandfather sitting on Durban’s stoep, clipping his toenails and refusing to hand over the inheritance his progeny is so desperate to spend. When the tide comes in in the late afternoon, as the legend goes, so the water table rises. Kingsmead, like the spectators at Castle Corner, begins to float and seam bowlers get to swing.

Kingsmead is a colosseum in which warriors have cut their enemies down before a baying crowd for a modest entry fee for a hundred years. It has also seen players cower in despair as unanswered blows rained down, and there was nothing they could do. It has showcased the finest cricketing talent and hosted the most intriguing games, some of which are described in the pages that follow.

How do you write a story of a stadium that has seen a million overs bowled? But Kingsmead is also a stadium that excluded Black people from this “Imperium in Imperio” for nearly seven decades. As spectators, it forced them to sit in the narrowest of confines, with a view of play occluding more than it revealed. And if they dared to trespass into white areas, Kingsmead saw them frog-marched back to “their” place. It was said that in Rome, a slave could win his freedom through gladiatorial prestige. Apartheid didn’t even allow Black people to try.

How do we write about a place of such joy, a showcase of world-class talent that also excluded many, enforcing apartheid in miniature? How do you decipher mountains of scoresheets and newspaper clippings of Test matches through the twentieth century, revelling in worthy records but knowing that only the lahnees were ever picked?

Under the Group Areas Act, Black people were bundled out of their city homes and put on the move to barren townships in Natal just as swiftly as anywhere else. No communion of cricket was observed here. Clubs that existed for over half a century were destroyed with the stroke of an administrator’s pen, with a bulldozer often moving in not long after.

Can one tell a tale as complex as this without going off in different directions, losing the story’s spine? In one of those coincidences in life, I picked up a book that has nothing to do with cricket. As I read, I realised that it offered clues to understand the game we all love, both within and beyond the boundary. That book is Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (1970).

On the final page, Marquez reveals Aureliano Babilonia Buendia deciphering a set of parchments which five previous generations of Buendias had studied. The meaning of the parchments suddenly became clear to Aureliano Babilonia. He realised that his mission was not about the past: “… he began to decipher the instant that he was living, deciphering it as he lived it, prophesying himself in the act of deciphering the last page of the parchments as if he were looking into a speaking mirror.”

Perhaps the history of Kingsmead can only be written when it is liberated, when new heroes untainted by past inequities emerge, a place where everyone can find hope for their children and a seat for themselves. Perhaps it also means that this history can only be written when past victims have exited the stage or are too old to settle scores or obtain apologies.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Beautiful sorrow: The tail end of a new innings for South Africa and its dogged survivors

As I wrote this book, I had to remind myself constantly that people, black and white, now entering their mid-forties, had been schoolchildren when democracy came. Most of the protagonists of Old Kingsmead experiences are septuagenarians. Maybe that is why Garcia Marquez tells us, “No one must know” the meaning of the parchments “until they have reached one hundred years of age”. For that is when the events described can no longer be felt directly on the body when the pain is the next big game.

The first Test match at Kingsmead was played in 1923. It was the first tour by an English team since the World War. The War, where so many cricketers met their death, was hauntingly captured by Siegfried Sassoon: “I see them in foul-dug-outs, gnawed by rats/And in the ruined trenches, lashed by rain/Dreaming of things they did with bat and ball.”

Read more in Daily Maverick: ‘Wounded attachments’ — a centenary of Test cricket at Kingsmead and the death of an unsung maestro

There is a Kingsmead connection. Karl Otto Siedle, who played for Natal against the MCC in 1913, was among those who died in the War. His brother Jack was an opening batsman for the Springboks. The Karl Siedle Memorial Clock at Kingsmead was built in his memory. It stood for a long time at the corner that marked the Non-European section. Now it stands at the entrance to the main grandstand.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is preoccupied with memory in the midst of forgetting. We live in a similar time of intense interest in the past. In Garcia Marquez’s town, there are civil wars, the coming of the railroad and plantations that portend ruin. Kingsmead has known all this. But it stands as a living symbol of the endurance of beloved institutions.

After the third Test at Kingsmead against the visiting Australians in 1957/58, Springbok batsman Roy McLean thought this would be “the last Test match to be played at Durban’s famous ground. In the not too distant future a new stadium for cricket and soccer is to be built nearer the sea-front.”

But Old Kingsmead was saved from the bulldozers. Unlike New Kingsmead and now Moses Mabhida Stadium, the cricket ground still has a few trees, a grass bank and the old stand, which once housed the players’ change rooms. New stadiums are sanitised. Lego-block affairs, without past and future. Kingsmead displays an architecture out of place, with brutalist banks and gleaming office parks all around the stadium. It sits at a slightly odd angle and could be seen as slightly old school, but doesn’t care. It is like a grandfather sitting on Durban’s stoep, clipping his toenails and refusing to hand over the inheritance his progeny is so desperate to spend.

Kingsmead’s pitch location slightly below sea level has given rise to folklore handed down through the generations. When the tide comes in in the late afternoon, as the legend goes, so the water table rises. Kingsmead, like the spectators at Castle Corner, begins to float and seam bowlers get to swing.

Kingsmead faces incredible challenges today. Test cricket in this neck of the woods is batting on a crumbling wicket. The T20 game is beholden to the most crass of commercial interests. But we have been here before. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, miraculous happenings occur. But these miracles are not of divine intervention or saintly character; Father Nicanor drinks a cup of hot chocolate before his lévitation. Reme dios, the Beauty, is in the throes of folding sheets before she rises into the sky. It is the mark of the longevity of an institution that it can survive years of mundane and even insalubrious events unfolding around it. Kingsmead, as the pages of this book will reveal, has been the venue of many a last ball and tail-end miracle.

Read more in Daily Maverick: ‘More than victory or defeat’ — A Kingsmead cricket tale without beginning or end

Like One Hundred Years of Solitude, a journey through the history of Kingsmead is a journey through the passions and quirks of the characters who came before us. It is virtually certain that someone, a century from now, will also shake their heads at our blind spots and pretensions. There are doubtless things we don’t see in our society that sully the game.

A century must pass before our own illusions and delusions can be untangled.

Kingsmead is a place drawing in the custodians of the game. But, like a firework, it is also a keeper of moments of special intensity. One of these was in 1992, sitting in the stands with my father, hardly a word passing between us, nodding when a fine shot was played. There are many spectators like me, thousands over time, for whom the name Kingsmead symbolises something precious and intimate. Paradoxically, for us, sitting in the main stand, this moment was imbued with extra grace, a sense of overcoming.

Cricket, of course, is a game of boundaries. But it is also a game in which boundaries are pierced, and crowds feel part of the action like never before. Kingsmead was built before spectator control was an issue. There are still large parts of the ground where you are close to the game. You can hear the fielders chew their gum. It is plonked in the middle of a sultry city, with crowds that span the generations, and a new coterie of youngsters mad about the sport.

One feels that after a hundred years, Kingsmead is ready to give up some of her most amazing stories. And after that, it wants to compose an innings open to all. DM

The book will be launched at Kingsmead on 9 December at 1pm – 3pm. Copies are available from Ikes Bookshop, Durban.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Why is it that Kingsmead seems to be left out in the cold by CSA as regards important cricket matches nowadays