‘An artistic, a social event does not reflect the age. It is the age. Cricket… is not an addition or a decoration… that one adds to what really constitutes the history of a period. Cricket is as much part of the history as books written are part of the history.” CLR James

In March 2003, Shane Warne arrived in Phoenix, Durban. A local entrepreneur had arranged for him to visit a few schools.

Warne was at his diuretic best as he generously mixed with the locals. And then something magnificent happened. One of the province’s greaTest spin bowlers, now residing in Phoenix, arrived. His name, Toplan Parsuramen. Parsu, as he was popularly known, was, tragically, a stranger to the people gathered. Warne, though, had been briefed, and for once stayed on script, giving Parsu a warm hug.

A mat was laid out and the two great spinsters bent their arms.

Despite his humiliating World Cup expulsion, Warne was in his prime. Parsu, 69 years old, was frail and slightly stooped. But one could sense his joy at meeting Warne and the gasps as Parsu turned the ball both ways.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, I watched Parsu bowl at Asherville Grounds, playing for his beloved Clares. He had a longer-than-usual run-up for a spinner. The matting wicket forced bowlers to rely more on guile than spin. And Parsu, for all his shy smile and humility, was a trickster. Many pedigreed batters saw the looping ball, and their eyes would light up as if the lunchtime breyani had arrived early.

But so much was in the flight, the ability to get the ball to dip and skid, the batsman vainly trying to step back as his torso fell forwards and he would be done.

Parsu grew up in the immediate shadow of Kingsmead. His father, Topsy, was a groundsman, one of 10 families employed by the City to look after the sports fields. Cramped for space, Parsu hung about on the boundaries of Kingsmead. He was not allowed to play at Kingsmead, let alone throw a few balls on the grass wicket.

But from an early age, he watched and made his mental notes. He grabbed an opportunity to to work the scoreboard. He also got to bowl to Dennis V Dyer, the Springbok opening batsman, in the Kingsmead nets. After a few hours, Dyer would throw him a coin or two.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Ways of (not) seeing: Cricket and its discontents”

It was here that Parsu developed the “wrong un”. Dyer did not have a long career in the Test team. He was deemed too cautious and hesitant. If you had Parsu as your net bowler, it might introduce some trepidation. Both of Dennis’s sons would go on to play provincial cricket on fields denied to the invisible Indian maestro.

Despite the exclusion, Kingsmead held a special place in Parsu’s heart. When I spoke to him in the early 2000s, he told me that it was the 1948 Test match between the Springboks and England that he most remembers — arguably the greatest Test played at Kingsmead in the era of racial segregation.

Knowing the cracks in Kingsmead’s racial wicket, he sneaked in and found a spot near the sight screen on the last day. The English were set to make 128 to win. Time was a factor, as there were barely 30 overs to be bowled. Wickets fell evenly. Then, 19-year-old Maritzburg University student Cuan McCarthy, in a burst of sustained fast bowling, took six wickets, including castling the great Denis Compton for 28. John Arlott’s reportage on the last ball is riveting:

“No man was ever driven by fate than Tuckett: he had to bowl the ball: Gladwin had to face it. South Africa could not now win, but they could lose. A no-ball, a wide, a leg-bye, a run-scoring stroke by Gladwin and the game was gone. Tuckett ran up and bowled; as he did so Bedser, the non-striker, left his crease and began to run. The ball was short of a length… Gladwin planted his leg down the wicket and swung, the ball hit him high on the thigh… Bedser was upon him. Almost in his crease: Gladwin set off running madly. The ball rolled no more than a couple of yards… Gladwin was running too much in their line to the wicket to allow a run-out at his end, and there was no wicket-keeper at hand to run out Bedser… “Defeat was glory in such a struggle, victory made us a little lower than angels’.”

By the time the Test was played the National Party, sprouting apartheid, had snuck into power. Arlott would not have noticed a slight boy on the edge of the sightscreen watching the game, hoping one day he could don his whites and take to the field of play. The year before making his debut for Rovers in Sea View at the age of 14, he returned figures of 9 for 37!

After the Nats came to power, John Arlott became a vocal critic of apartheid cricket. He famously organised for Basil d’Oliveira to leave South Africa for England. Whatever hopes Parsu had of playing at Kingsmead were smashed. He also dreamed of going to England, holding off marriage, and playing the sweepstakes, but without a benefactor, it was a doomed project.

A moment etched into the memory is when D’Oliveira came to Durban in February 1967. I was eight years old. My father and I arrived early at Curries Fountain to watch an all-star game.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

In the second innings, Parsu bowled D’Oliveira for one. I was disappointed. But there was a treat to come. After the match, D’Oliveira bowing to our entreaties, took on the Natal bowlers and an amazing batting display ensued… in a series of dazzling strokes, he scored 101 runs in 25 minutes off 48 balls with nine sixes.

On the walk back to our first-floor flat, I played the shots over and over again. On that day, my love of the game was born. It never dimmed, despite my inability to play with a straight bat and having the concentration span of a fly in a sweetmeat shop.

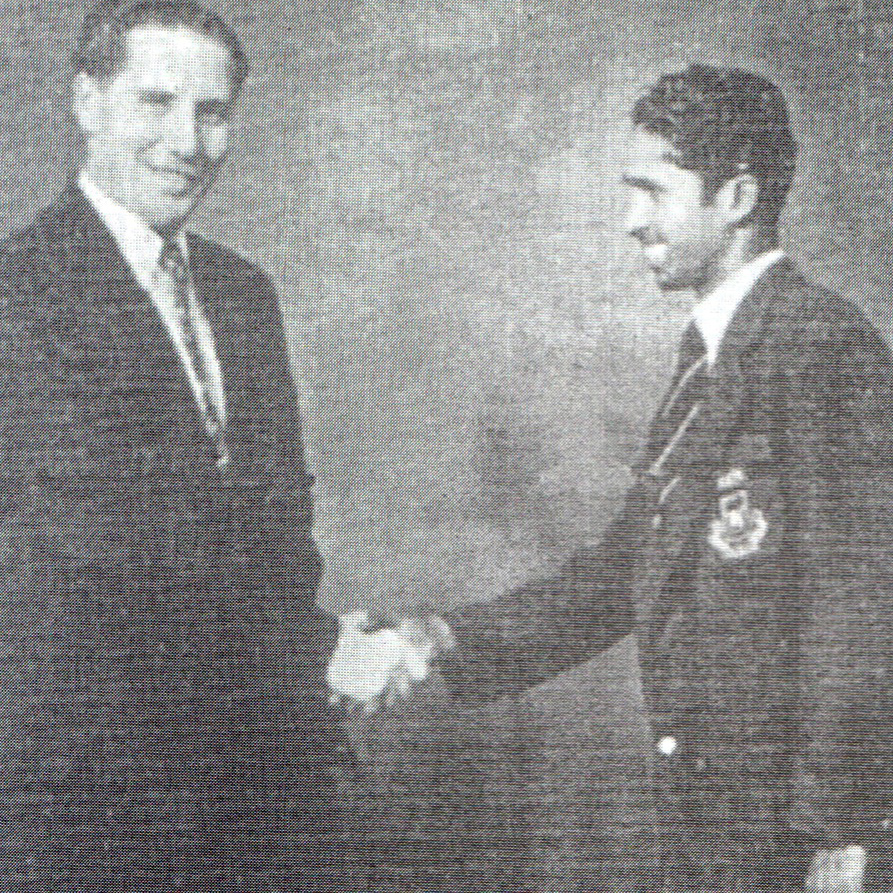

In the age of apart-hate, there were camaraderies nurtured even if they could not be shared on the cricket ground itself. One thinks of a lovely 1956 photograph of Springbok Roy McLean and Parsu now playing his cricket in Mayville, dressed in blazers, shaking hands.

Roy McLean and Toplan Parsuramen.

But non-racial cricket was unorthodox, and threatening. Starved of resources, it went into severe decline. Parsu would keep playing for Clares, but it was for love rather than competition. And, under international isolation, many a would-be Roy McLean and Dudley Nourse would have their talents confined to the bastions of white exclusivity in a South Africa built for them.

Parsu’s innings came to an end the year that Kingsmead celebrates its centenary of Test cricket. Kingsmead, the venue of the Timeless Test and the Friendship Test against India as apartheid fell.

As much as this bastion of cricket hurtfully excluded the Parsus and D’Oliveiras, Kingsmead came to play a role in a much bigger game — the struggle for democracy. It became a target that anti-apartheid forces could aim at.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Slouching towards Varanasi to be reborn — on a journey to India, I find my roots in Durban”

While many white cricket lovers looked for the shadiest places to sit or found a spot around their favourite fielder, many black cricket lovers, with heavy hearts, shunned the venue, the diehards following the game through the voice of Charles Fortune.

Attitudes hardened as the South African Council on Sport headlined the slogan, “no normal sport in an abnormal society”, threatening excommunication to those who sat in Kingsmead’s “non-white” strip.

When I began to talk to ex-cricketers about recognising Kingsmead’s 100 years of Test cricket, I sensed what philosopher Wendy Brown calls “wounded attachments”.

There are those who asked: how can we recognise a stadium that for much of the 20th century did not recognise us? For them, the present is always trumped by occupying the high ground of the past. Others want us to play abnormal cricket for the rest of our lives, with Kafkaesque racial bean counting. This is fuelled, of course, by white apartheid cricketers still fixated exclusively on their own wounds as if the Parsus of the world did not exist.

The tragedy in all this is, as Jean Améry puts it, “resentment blocks the exit to the genuine human dimension, the future”.

Is Kingsmead not as much Parsu’s as it is Roy McLean’s? In 2014, Parsu was awarded a Heritage blazer by Cricket South Africa. The circle between Mclean and Parsu about 58 years later was made complete.

More than three decades have passed since cricket unity swept into place. New generations come not to watch Test cricket but 20/20. There is music and dance. You can make a couple of million if you take a one-handed catch. To snatch a hug and a peck on the lips at Cow Corner.

The stadium is full of life. It has a vibe. Long shadows are cast by late-afternoon capitalism. Commerce and consumerism has wholly entered cricket. Bags are checked for food. Broadcast and advertising interests affect rule changes.

The cricket world of John Arlott and CLR James are on the tail end. Players scarcely know the city to which they swear allegiance and which they will, after a few weeks, leave for another city and another badge. In the boardroom there is talk of the bottom line rather than the batting line-up. But still, thousands pitch. What do we know that only Test cricket knows? Clearly, very little.

In 2023 , 100 years since the first Test was played, one likes to imagine Kingsmead as the venue, where despite past injury and present dangers, the families of Parsu and McLean might find themselves sitting a blanket apart.

And, in the frenzy of a shattered wicket or stupendous six, they applaud or groan hoarsely together, in this wounded but ever-hopeful land. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.