ANTARCTICA

The man from the Little Karoo who led SA to South Pole

With accusations of Russia violating the Antarctic Treaty by prospecting for fossil fuel and a demonstration against a Russian Polar vessel docking in Cape Town, the frozen continent is getting considerable attention right now. South Africa is a signatory to the treaty and how that happened is a fascinating story.

South Africa’s presence in Antarctica had its roots in a madcap scheme dreamed up in 1949 by the explorer Sir Vivien ‘Bunny’ Fuchs and a South African geologist, Ray Adie.

While confined to their sleeping bags in the mountains of Alexander Island off the Antarctic Peninsula during a blizzard, they hatched a plan to undertake the journey clear across Antarctica. It would be the one Shackleton failed to make in 1914 when his ship, Endurance, was crushed by pack ice. Maybe South Africa would be interested, suggested Adie, considering that the Weddell Sea area closely affected weather conditions in the southern hemisphere.

Read more in Daily Maverick: “‘It’s a moral disgrace’: Cape Town mayor spits fire as Russian seismic ship sails to Antarctica”

Fuchs was a man with influence and, by 1955, his dream had become the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition with Britain’s new Queen Elizabeth ll as its patron. Financial support came from Britain, New Zealand, South Africa and Australia. On his team was no less than the man who’d first stood on top of Mount Everest, Sir Edmund Hillary.

The person chosen to represent South Africa was a remarkable character named Hannes le Grange, a 28-year-old employee of the SA Weather Bureau who’d grown up in the small town of Ladismith in the Little Karoo. According to Fuchs, he was “something of a blind date”, but got the explorer’s approval because “he was tall and heavy in build.”

Hannes le Grange. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Tractors used by Edmund Hillary’s Trans-Antarctic expedition. Image: Cliff Dickey / US Navy / National Science Foundation

The plan was for Fuchs to set up Shackleton Base on the ice shelf edging the Weddell Sea, and for Hillary to establish Scott Base on the other side of the continent near McMurdo Sound on the Ross Ice Shelf. From there he would lay supply depots for the trans-continental party to use on its run from the Pole to Scott Base.

In November 1955 Le Grange, together with Fuchs, Hillary and other members of the party, set sail for the Weddell Sea in a Canadian sealer, Theron. Aboard were stores and equipment plus a Sno-cat, two aircraft, some track-adapted Ferguson farm tractors and 24 huskies. They had a hard time getting through the pack ice, but finally made it to the ice shelf and began to offload stores for the advance party base.

The great blizzard

Fuchs had planned to overwinter there, but a blizzard threatened to demolish the Theron. It parted its cables and was forced to stand off while the men tried frantically to retrieve drowned or floating boxes. Later that day the Theron returned but the storm was closing the pack around it and, after hastily picking up those who were not over-wintering, it sailed northwards, leaving eight men, including Le Grange, watching her disappear from sight.

All later attempts to reach the ship by radio failed. “Many of those who were going home,” Fuchs later wrote in understatement, “must have felt that in some way they were leaving their companions in the lurch.”

Beef and pork bar – early expedition food. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antartica

Early expedition food. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Early expedition food. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Herring for the expedition. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

The men had 300 tons of stores to shift before winter set in and they made their home in the Sno-cat packing case. Before they’d completed the hauling the weather became what Le Grange remembered as ‘the great March blizzard’ and the men were confined to their box for several days. On emerging, they discovered the ice had disintegrated at the offload site and had carried off a tractor, all the heating coal, the timber for a workshop, a boat, engineering stores and 300 drums of fuel. How they survived the winter is a miracle. In August the lowest temperature was recorded at -53ºC.

Next summer Fuchs returned with equipment and aircraft and, with the Shackleton Base refugees, began to lay inland depots before the onset of the second winter at Shackleton Base. Le Grange, the only meteorologist, was chosen to undertake the entire trans-Pole journey.

Depoting was a nightmare. The tractors kept breaking down and, with tracks added, were difficult to steer. Dog teams fared much better and were used to negotiate routes through the heavily glaciated terrain. While they were doing this, Hillary began laying depots from McMurdo.

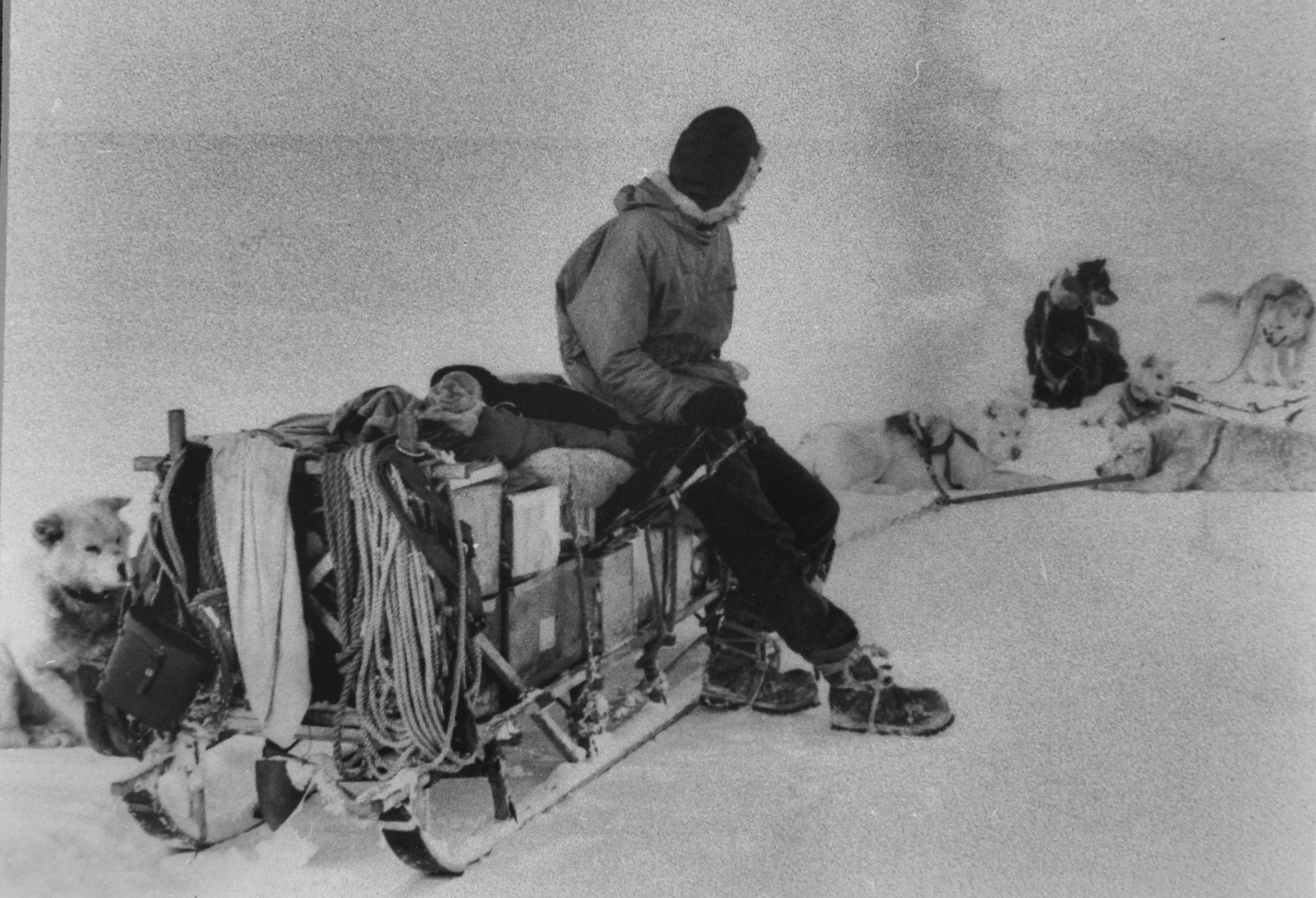

A husky team in action. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Stopping to rest the dog team. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Husky power was the original _transport system. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

At times, on the long haul across the continent, there were crevasses on all sides and vehicles had to be roped together. The snow bridges would often break and the vehicles would hang, sickeningly, over dark abysses. Three of these eventually had to be abandoned, but Fuchs pressed on, finally reaching the Scott–Amundsen Base at the South Pole. There they were greeted by an exuberant Hillary, who’d made it with only 90 litres of fuel left.

In late January, Fuchs’s party started out again in a race against winter. At one point they crossed 50 crevasses in the space of seven kilometres and were tied down by katabatic winds howling down the Skelton Glacier as they descended onto the Ross Ice Shelf. On 2 March they reached Scott Base, having travelled 3,472 kilometres in 99 days. From there they were ferried to New Zealand aboard the Endeavour from where Le Grange made his way to Britain where he was awarded the British Polar Medal by the Queen in Buckingham Palace, as well as a Royal Society Medal. After that, he sailed home to take up his duties back at the South African Weather Office.

A base on the ice

History, however, was not going to leave Le Grange in peace predicting rain or shine. In 1959 South Africa became one of the original signatories to the Antarctic Treaty. Under this extraordinarily broad accord, member states agreed that Antarctica would be used for only peaceful purposes, scientific investigation would be shared, there would be no territorial claims and nuclear testing on the continent was prohibited. Being part of Antarctica, however, required maintaining a presence and that meant establishing a base on the ice.

Conveniently, the Norwegians were planning to vacate their base in Queen Maud Land and offered it to South Africa. They also agreed to transport a party down on their vessel, the Polarbjorn, which would be passing through Cape Town in November of that year. In a flurry of activity the South African National Antarctic Programme (Sanap) was established and a national expedition, Sanae 1, given top priority.

SANAE’s first residents on Antarctica. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

The first SANAI 1 base under construction. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

The obvious man to lead it was Le Grange, the only South African who had ever set foot on the South Pole. He accepted, but with only three months to find a team and purchase supplies, he became like a man demented. He flew to London and, with the help of Sir Vivian Fuchs, bought clothing, sleeping bags, instruments and both man and dog rations.

Next stop was Oslo where he got the run-down on the Norwegian base and also ordered fuel, then to Berlin for meteorological equipment, then to Denmark to negotiate the purchase of a Polar vessel, but without success. After that it was back home to choose his team, none of whom had polar experience.

The Polarbjorn sailed in early December 1959 and soon encountered problems. In heavy seas, a steward, emptying a bin, slipped and fell overboard. He was never found. Soon afterwards the vessel’s engines broke and had to be repaired at sea. Then one of the officers blew himself up with dynamite brought along to break up ice floes.

Within the Antarctic Circle, they were in danger of being frozen in, only being saved by the chance appearance of an Argentinean icebreaker, San Martin. They finally reached the shelf five weeks after leaving Cape Town. The Norwegians hastily departed, fearing they’d be iced in, leaving the first South African Polar expedition waving on the ice.

Building the second South African base, Sanae 2. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Stuck in a crevasse. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

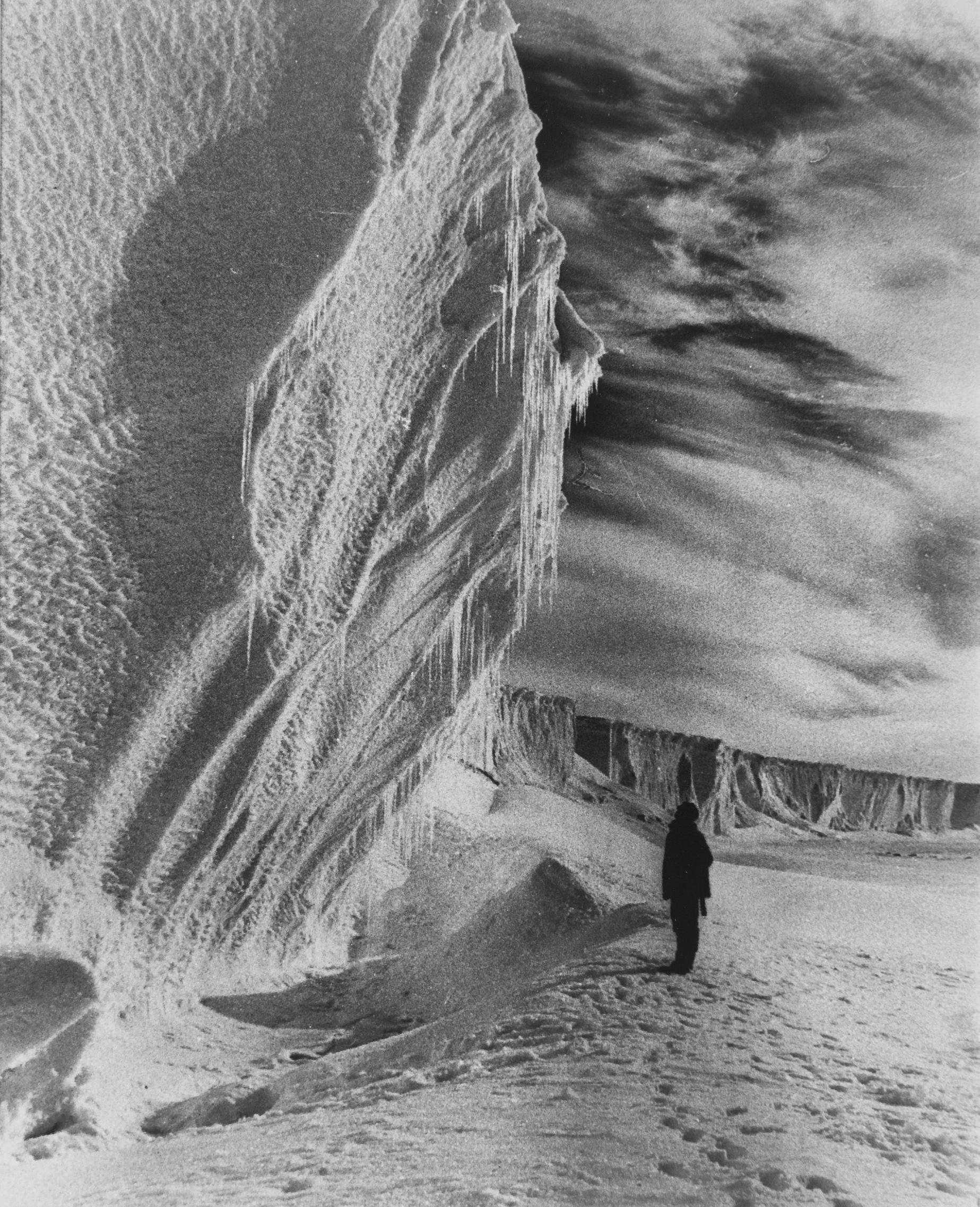

The ice edge of Antarctica. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Huskies were eventually replaced by tractors and their departure was mourned by polar teams. Image: SANAI 2 base museum in Antarctica

Norway Station was showing signs of ice damage. By then it had been buried by seven metres of ice and some roof beams were bending and cracking under the pressure. There was a generator, but they had not brought replacement bearings and were forced to improvise with leather. The labels on the many tins left by the Norwegians were unreadable, so they never knew what they’d find when they opened them; and they had similar problems with instructions on equipment. Still, they managed, even organising a month-long dog-sled journey inland to survey the inland nunataks (snow-drowned mountain peaks) in the region where Sanae 4 is now situated.

The team arrived back in Cape Town in January 1961. There was a welcoming party at the Castle and they received the country’s first Antarctic Medals. Their winter occupation of Norway Hut laid the foundation for South Africa’s presence in Antarctica and kicked off the country’s Antarctic programme. There has been an over-wintering team in Queen Maud Land ever since.

Soon after his return, Hannes le Grange and his expedition members formed the SA Antarctic Club. He later became an urban planner, after which the first South African to reach the pole retired to Hermanus, where he died in 1999. The South African National Antarctic Programme (Sanap), which he pioneered, is alive and well and is in its 63rd over-wintering year in Antarctica. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thank you for a fascinating article on a topic about which I knew nothing. Will definitely read up some more.

Keep ’em coming Doc.

My fascination with Antarctica started with reading about the early expeditions. I will be visiting the white continent for the first time in December 2023 and want to read more about the South African exploration/presence there. Are there books describing this?

Please share where the above information came from.

You could look at my book Blue Ice if you can find a copy, Alan. If not contact afpress at iafrica dot com

Thanks for the history. Good to know that SA has a vested interest in our southern neighbour.