MERE IMMORTALS

Endurance’s watery grave: SA Agulhas II plays major role as Shackleton’s legendary ship is found after 108 years

An expedition team aboard the SA Agulhas II has located Ernest Shackleton’s doomed ship that he lost in Antarctic ice floes in his failed attempt to reach the South Pole.

She was called Endurance and she endured much in the freezing seas around Antarctica. But, after a six-day gale, the ice eventually got her and she lay, trapped for 10 months, drifting with Ernest Shackleton and his 27-man crew living aboard.

But as the cold, dark Antarctic winter approached, the ice squeezed her sides until her timbers cracked. According to photographer Frank Hurley, they could hear the ship suffering. “It was crying like a wounded animal.” On 21 November 1915 her hull, crushed by pack ice, flooded and she sank into the dark depths of the Weddell Sea.

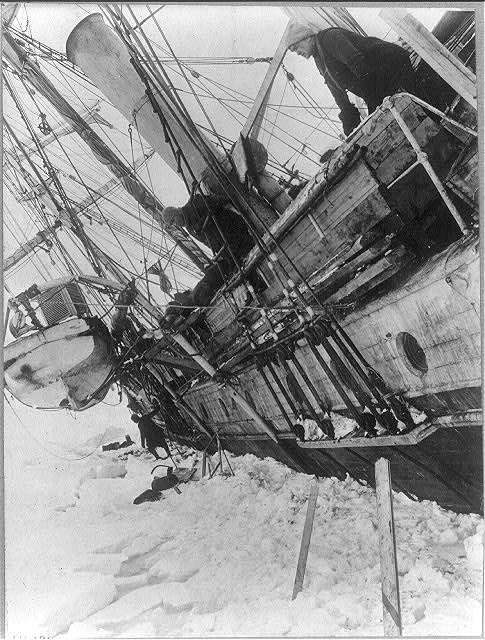

The last moments of the Endurance during Shackleton’s expedition to the Antarctic. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

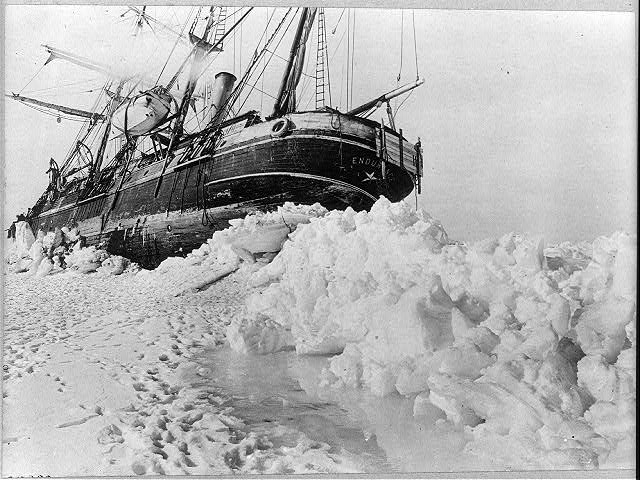

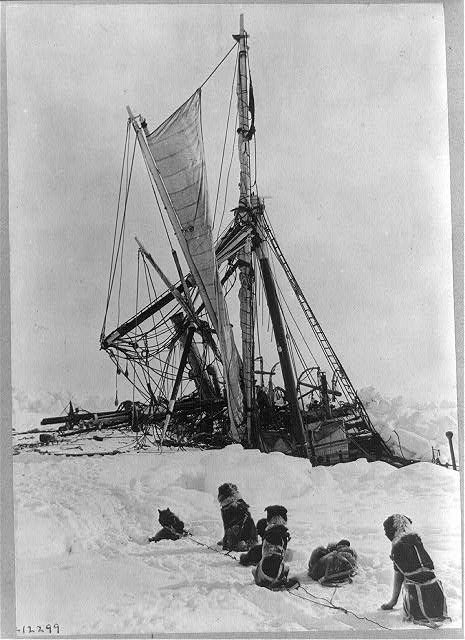

Endurance squeezed between an ice jam. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

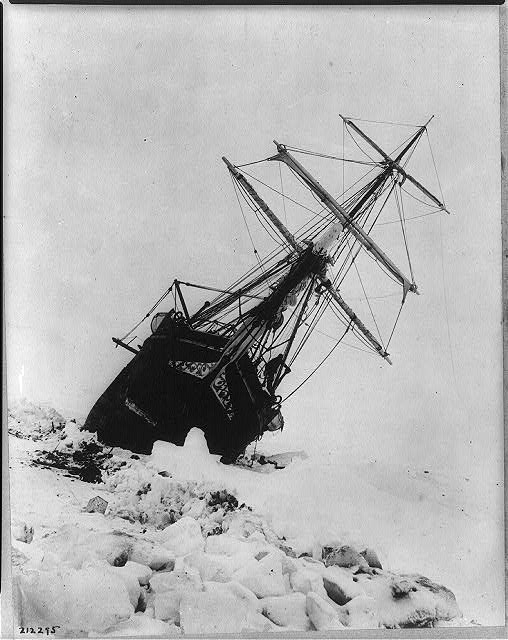

Endurance was stuck in the ice for two months before she sank in the Weddell Sea on Oct. 27, 1915. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

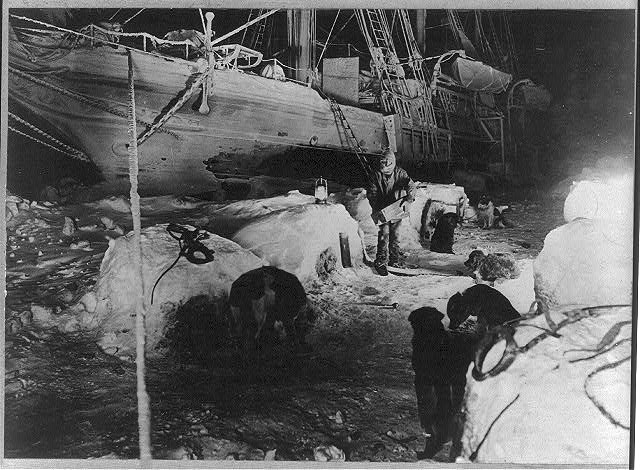

Faithful dogs being fed in the ice kennel, while Endurance was stuck fast. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

A winter flashlight scene in the Weddell Sea, showing Endurance stuck fast. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

A titanic upheaval. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

Her crew knew it was coming. They had offloaded as much as they could, including three lifeboats. Hurley captured the ship’s last hours and the journey in brilliant glass-plate photographs that have survived.

Shackleton wrote: “We have been compelled to abandon the ship, which is crushed beyond all hope of ever being righted. We are alive and well and we have stores and equipment for the task that lies before us. The task is to reach land with all the members of the expedition. It is hard to write what I feel.”

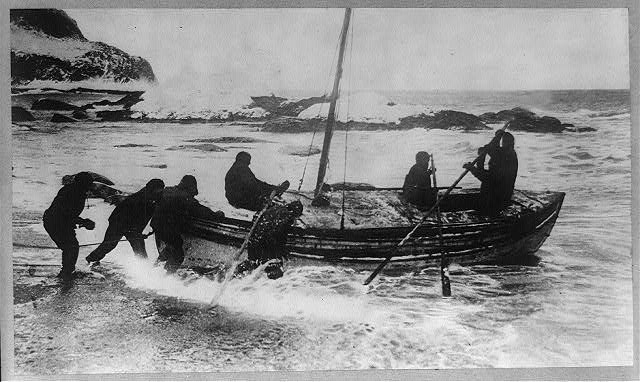

Much has been written about the bitter trek by the 28 men to Elephant Island, dragging heavy lifeboats.

Endurance after ice pressure was released. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

Sir Ernest Shackleton to the rescue. Members of the expedition in push a lifeboat off shore after they had to abandon ship when Endurance sank. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

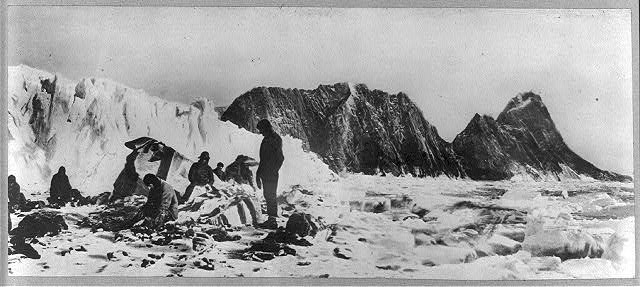

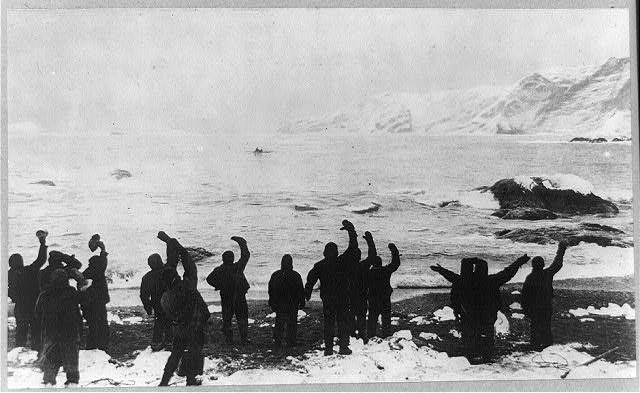

On Elephant Island where Sir Ernest Shackleton found lost party. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

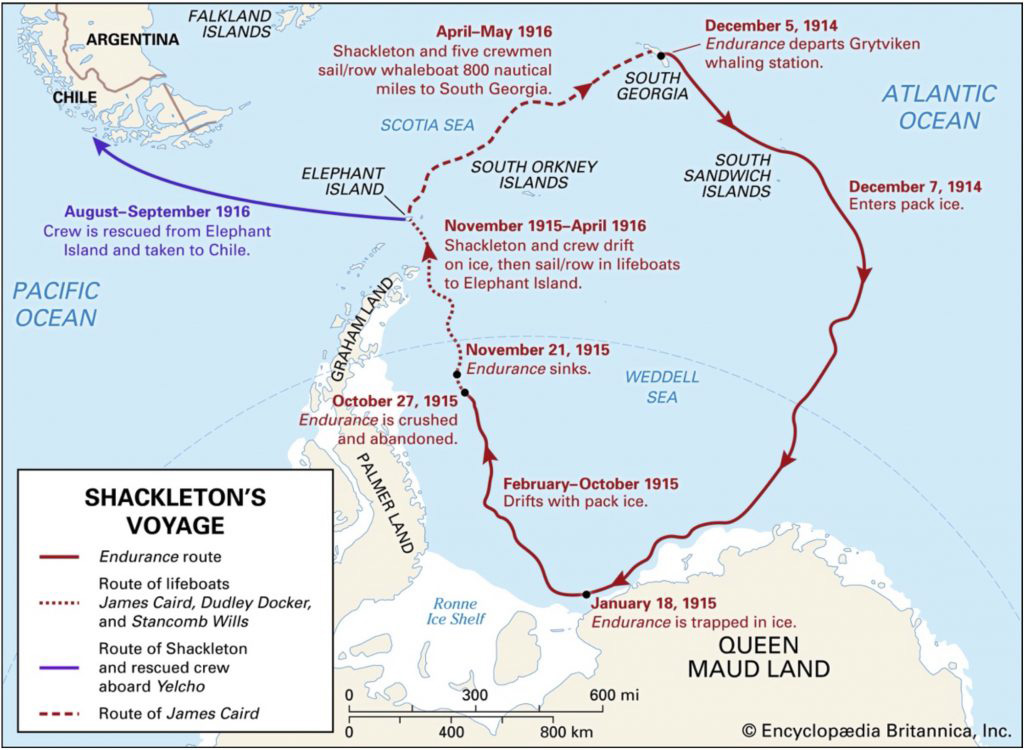

Shackleton’s voyage. Encyclopedia Britannica. Image: WikiCommons

From there, Shackleton and five others used one of the lifeboats, the James Caird, to sail to South Georgia. Shackleton and two others then crossed the mountainous, snow-clad island to the whaling station at Stromness to raise the alarm and seek rescue. The remaining expedition members were rescued from Elephant Island on 30 August 1916.

Lost party on Elephant Island saved at last. Image: Hurley, Frank, 1885-1962, photographer; Underwood & Underwood, copyright claimant; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

Shackleton never reached the South Pole but attained even greater fame than Robert Falcon Scott who did, because he never abandoned his crew and saved every one of them.

The Endurance, the ship that couldn’t be saved, receded into history for more than a century. But suddenly, looming ghostly, beautifully in the icy waters, it has returned, discovered on the ocean floor by the Endurance22 Expedition led by Dr John Shears.

The Endurance, lost in the iciest waters on Earth, was until this month among the most celebrated shipwrecks that had not been found. The announcement, broadcast from South Africa’s expedition ship SA Agulhas II on March 5, was simple and electrifying:

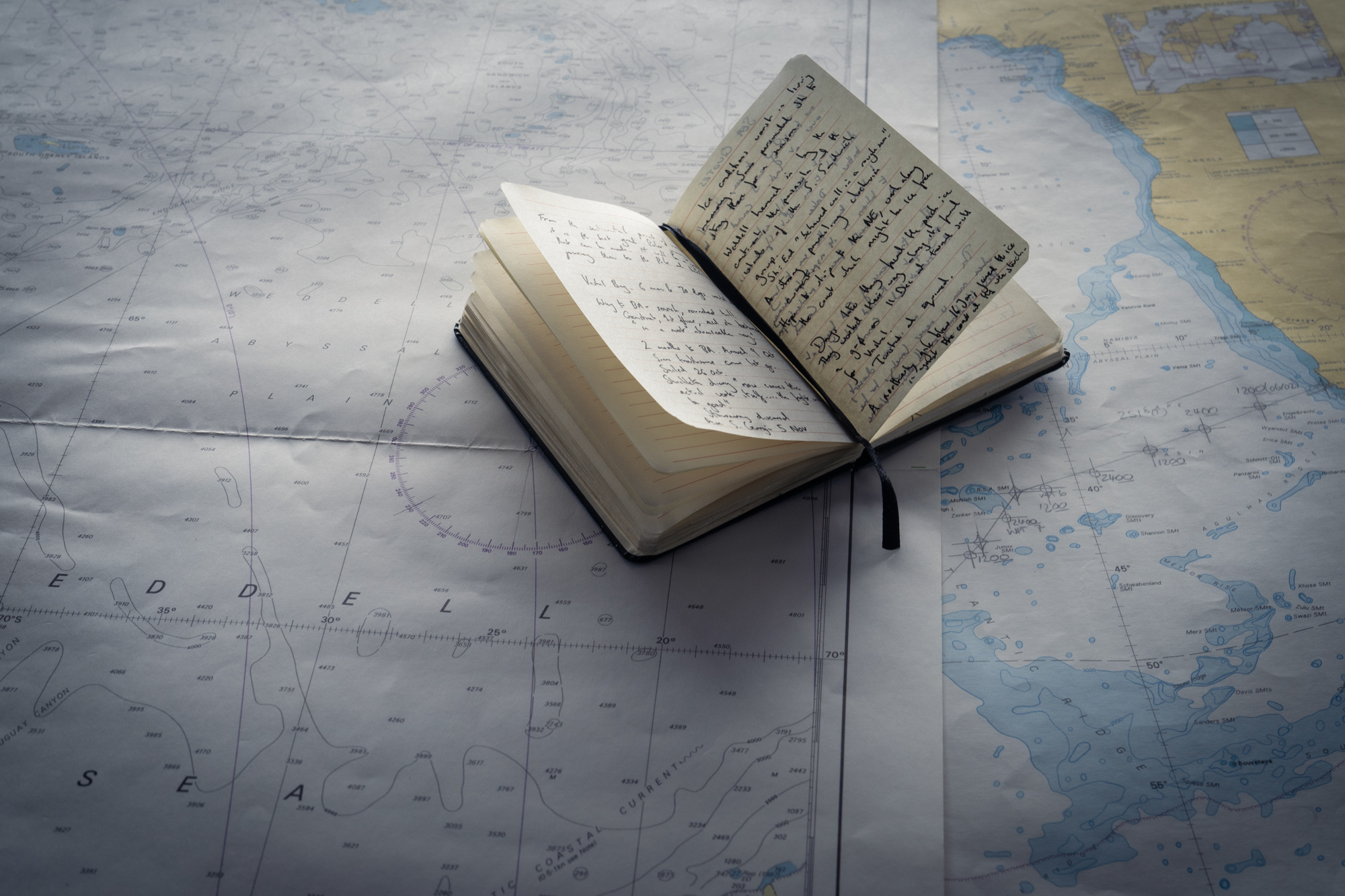

“We are pleased to confirm that the Endurance has been found at 3,008 metres deep in the Weddell Sea. It was within the search area defined by the expedition team before its departure from Cape Town and approximately four miles [6.4km] south of the position originally recorded by [Endurance’s] Captain [Frank] Worsley.”

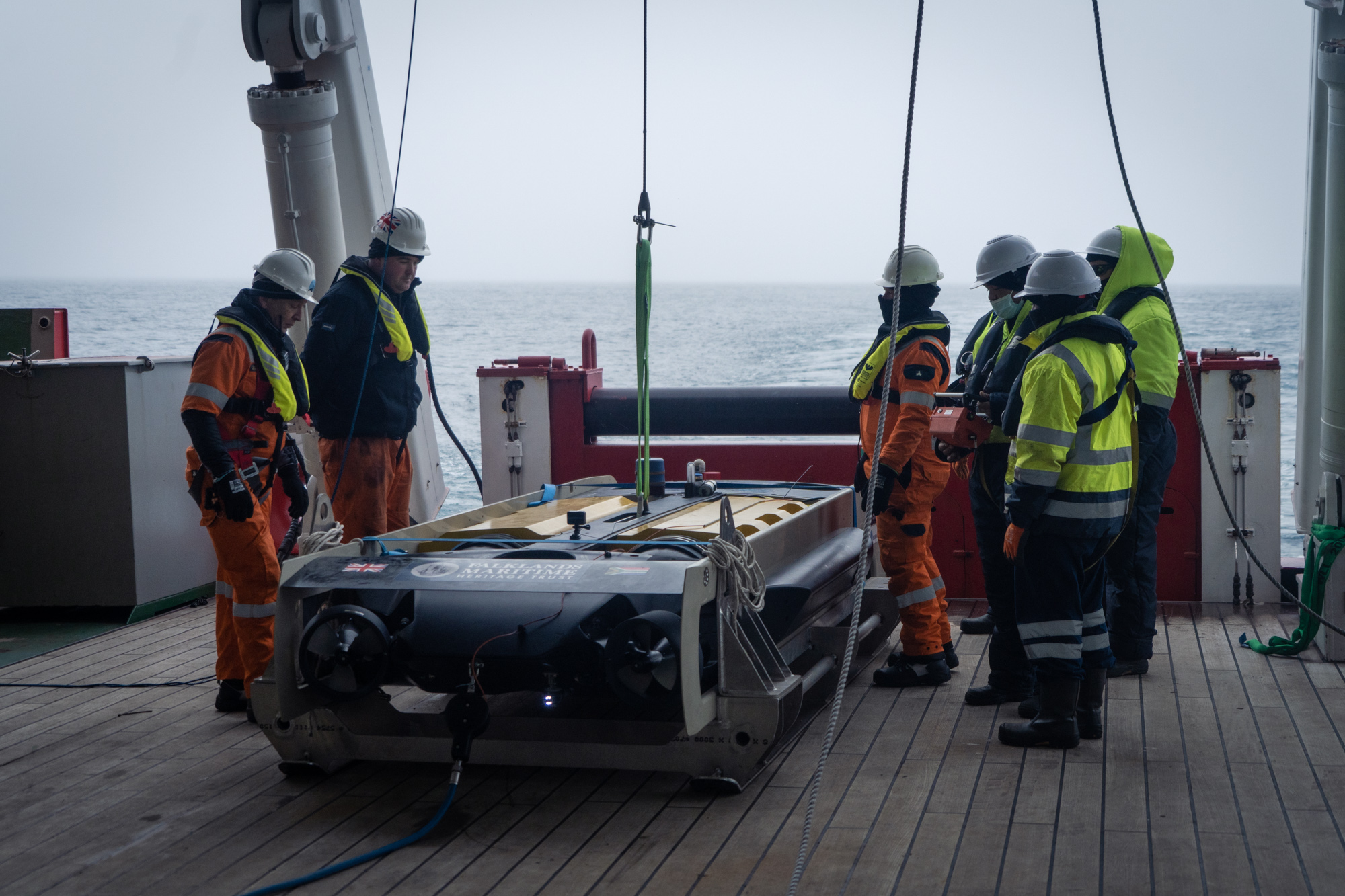

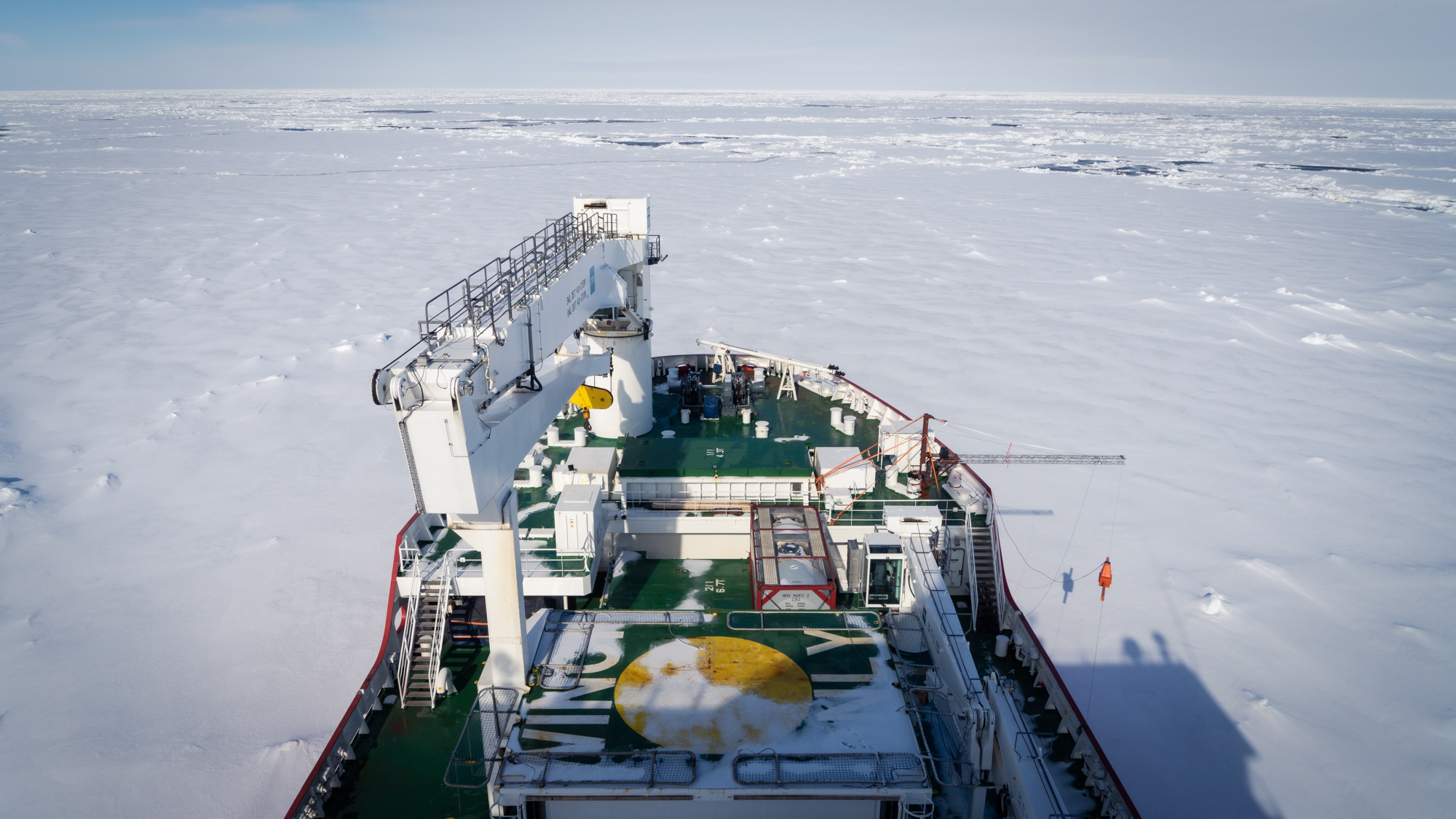

The ship was located by an extraordinary, untethered underwater vehicle, a Saab Sabertooth, operating from the South Africa research ship. It can reach sites up to 160km from the ship and return with photos, video and survey data. This means that even if the sea ice conditions are difficult, the expedition can survey a wreck it cannot reach.

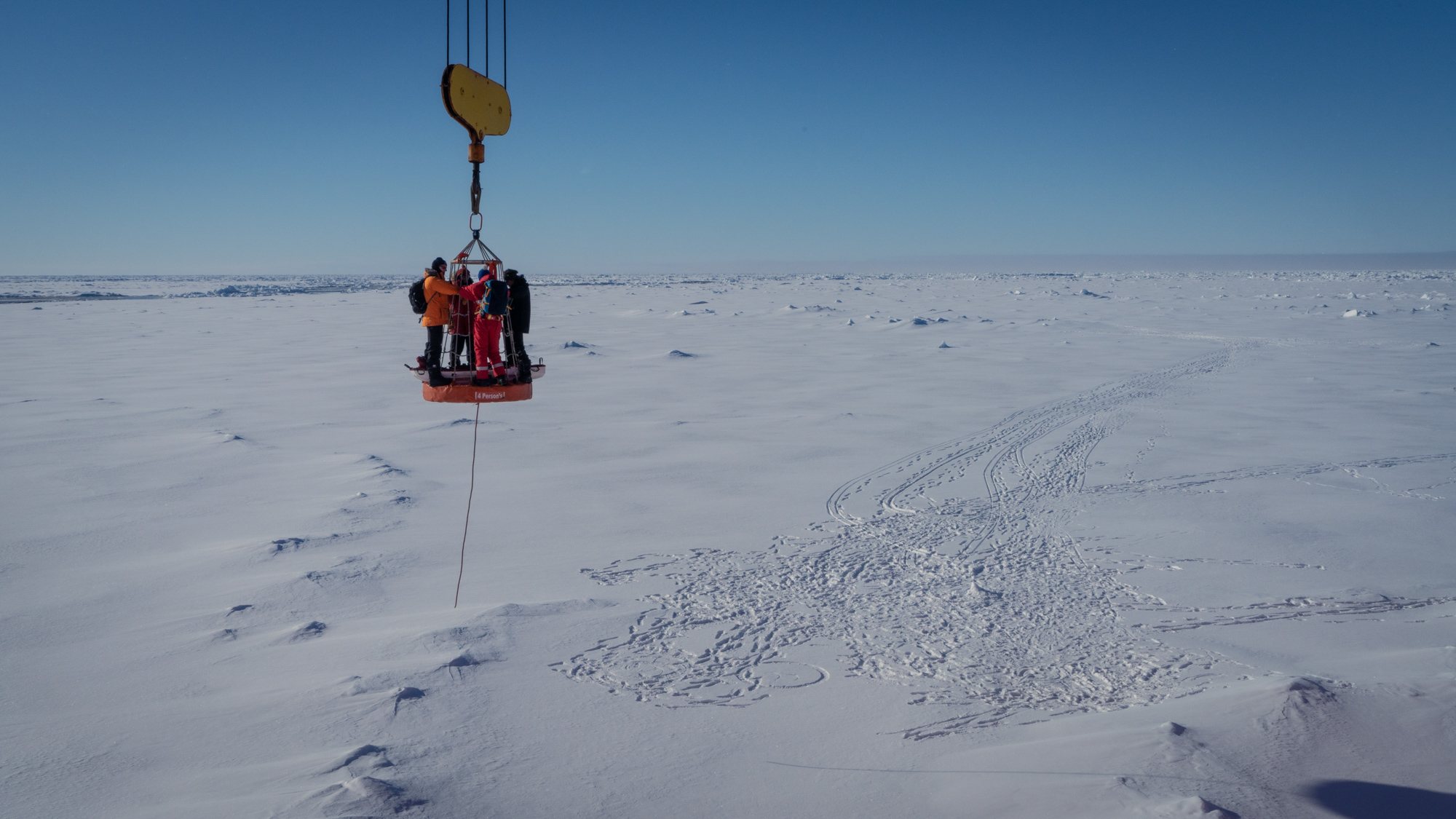

SA Agulhas II in the ice. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and James Blake

SA Agulhas II. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and James Blake

SA Agulhas II. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Landscapes. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

On board of the SA Agulhas II. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

On the bridge. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

On the bridge. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Saab Sabertooth. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Saab Sabertooth. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Saab Sabertooth. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Landscapes. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Landscapes from the SA Agulhas II. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Penguins. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and Nick Birtwistle

Penguins. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and James Blake

The photographs it returned with, as you can see, are crystal clear, hauntingly sad and at the same time thrilling. The Endurance will now be surveyed by the Sabertooth’s laser scanner to produce a 3D model and high-resolution photographs of the wreck and its debris. This will allow the wreck, together with its equipment, fittings and contents, to be recorded to a level of accuracy comparable to that of an archaeological survey on land. As science goes, it’s up there with a Moon shot.

Endurance shipwreck discovered by the Endurance22 Expedition – Endurance22 Discovery

Endurance shipwreck, starboard. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and National Geographic

Taffrail and ships wheel aft well deck. Image: Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and National Geographic

The Endurance was a beautiful, three-masted schooner launched from Sandefjord in Norway in 1912. More than 40m long and 7.6m wide, she was built under the supervision of the master shipbuilder Christian Jacobsen.

He was a stickler for perfection and insisted that all his craftsmen were not just skilled shipwrights but were also experienced in seafaring aboard whaling or sealing ships.

Every detail of her construction was scrupulously planned to ensure maximum durability. Each joint and fitting was cross-braced for maximum strength, a detail that allowed her to survive in the tight embrace of Antarctic ice floes for 10 months.

At the time of her launch, Endurance was arguably the strongest wooden ship ever built, with the possible exception of Fram, the vessel used by Fridtjof Nansen and later by Roald Amundsen, the first man to reach the South Pole.

She was originally named Polaris, an ice-capable steam yacht built to provide luxurious accommodation for small tourist and polar bear hunting parties in the Arctic. She had 10 passenger cabins, a spacious dining saloon and galley, a smoking room, a darkroom to allow passengers to develop photographs, electric lights and even a small bathroom.

Her keel members were four pieces of solid oak and she was clad in planks of oak and Norwegian fir. The bow, which would meet the ice head-on, had been made from a single oak tree chosen for its shape so that its natural shape followed the curve of the ship’s design.

When the owner got into financial difficulties, Shackleton bought her, stripped out the cabins to make storage room and had her painted black so she could be seen in polar conditions. He renamed her Endurance.

However, given her entrapment in the ice, she had a fatal flaw.

The Fram was bowl-bottomed, which meant that if the ice closed in against her, the ship would be squeezed up and out and not be subject to the pressure of the floes.

Endurance, on the other hand, was designed with great inherent strength in her hull in order to break through pack ice by ramming, but was deep and not designed to rise out of a crush. It was to be her undoing.

Announcing the find, Endurance22’s director of exploration, Mensun Bound, said: “We are overwhelmed by our good fortune in having located and captured images of Endurance. This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen. It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact and in a brilliant state of preservation. You can even see ‘Endurance’ arced across the stern, directly below the taffrail.”

Expedition leader Dr John Shears said the expedition would soon begin its return leg to Cape Town and paid tribute to the expedition team and the officers and crew of the SA Agulhas II, who he said had been outstanding.

“I would also like to say thank you to the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and all of our partners, especially in South Africa, who have played a vital role in the success of the expedition.” DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This wonderful achievement owes much to South African experts in their fields and their use of this knowledge to provide the world with an extraordinary end to a memorable piece of history sought for for so long. It ought to be the subject of a South African led public relations storm, reminding the world that for a small nation much damaged by successive bad governments, its people have remained

proud and purposeful in many arenas but not without a grave need to be so in many other areas. but for now let’s celebrate this grand historic moment in our naval and scientific communities.