LESSONS FROM MY FATHER

Gift of the Givers’ Imtiaz Sooliman on his dad — ‘His actions spoke loudly, far louder than his words’

Imtiaz Sooliman is a South African medical doctor and the founder and chair of the Gift of the Givers Foundation, an organisation that has, in the 30 years of its existence, provided extraordinary support to millions of South Africans. Here, he tells the story of how his dad influenced his journey.

Where do I start in talking about what I learnt from my father? There was just so much. To say that I was moulded by him is an understatement. So many aspects of who I am today are a result of the person he was, and what he taught me, through his words but far more through his daily actions.

My father Ismail Sooliman was born in Potchefstroom in North-West Province. His father had moved to South Africa from India and had set up a shop in Potch. Dad followed in his footsteps.

When I was very young, my parents divorced. It was a tough time for us, my father trying his best to look after my two sisters and me.

I’m going to start with what I learnt from my father in his position as a businessman. As said before, it was his actions from which I learnt the most. His actions spoke loudly, far louder than his words.

In the general-dealer shop which he ran — and which I helped in from when I was about 10 — most of his customers were black Africans, a great number of them poor. There were a few of the customers who were fairly well-off, but they were by far in the minority.

Most of the customers who struggled to make ends meet would buy on account; food, clothes, school stationery — all sorts. My father would treat each and every one of his customers with the same love and the same enthusiasm, and the same care. Actually, they were not just his customers, they were friends. No matter where you came from, or whether you were well off or very poor, he was the same with everyone. He carried with him the human values of kindness and caring for, respecting, and helping the poor.

It would often happen that he’d have a customer whose account was in arrears; he would say to his staff member who was unsure whether to allow the said customer to buy again on credit: “Look, this family’s mother supported us for a long time — it’s fine, give him more stuff. It’s OK.” My dad would know that in all likelihood, he wouldn’t get paid back, yet he would still give what people in debt needed.

And it would happen that those same customers, who couldn’t settle their food account, would experience the passing of one of their family members, and they would come to him, sometimes looking quite sheepish, explaining their predicament. “We need money for the funeral,” they would say, in very humble ways, “and we need some groceries for the funeral.”

My father — again knowing the chances of being paid were slim — would say in the back storeroom:

“Give it to them; maybe one day they will pay.”

Some of those accounts used to run for years. But, the beauty of it all is that sometimes — as many as five years later — someone would come and say, “You know what, I owed you this money five years ago; I’ve come to pay now.” My father would smile, nod, and say, “You didn’t really have to come and pay.” The customer would reply: “No — you gave me good service, and you’ve been good to me. I want to pay. I have to pay.”

Such was my father’s kindness. His ethics-based values are lacking in our society today; he was a good role model to me and to many others, and he had business ethics.

***

I loved working in my father’s shop; I learnt independence, and sometimes he’d pay me some money, even though I didn’t really need it. He bought a second shop and told me, “OK, you can run this shop. Do what you want.”

I’d come in after school hours and over the weekends. I had staff working under me. My father gave me leeway to apply my talent, to do whatever I wanted in the business. Sometimes it was hard to get customers in so I had to work out ways of getting them in. My father told me I could price the goods myself, explaining that I mustn’t put prices too high and that I should be competitive. His advice was: if people don’t have much money, then bring the price down; and sometimes just give it to them at cost, or even below. In certain situations, you can even just give it to them.”

My father showed me a lot of trust when I was running his second shop. It is the same value that I always try to apply in my work at Gift of the Givers: when I give people opportunities, I trust that they will make the most of them. And if they make a mistake (and I know they are going to make mistakes, as we all do) then I say they must learn from them. If it’s not a fatal mistake, or there’s no reputational damage, then it’s fine to make a mistake. And I trust that they will learn from those mistakes. That’s an approach I learnt from my father.

***

My dad loved his sport. He played some cricket as a youngster and was also a very competitive soccer player; the soccer was a bit before I was old enough to watch. Unfortunately, he hurt his ankle in an accident and had to pack it in.

In tennis, he was a very community-minded person, actively involved in a tennis club through the Western Transvaal Tennis Union. I would often go with him to the tennis courts. We’d have many tennis tournaments in Potch to which other clubs would come to compete, from places such as Rustenburg, Mafeking and Zeerust.

It was in tennis that I felt closest to my father. At the courts, it was great to be with him, whether collecting the balls — or when I was older — umpiring. It was so special just to be with him all the time, doing simple things related to the tennis matches and festivities afterward.

At the tennis club, I would see the same warmth and generosity of spirit in him that I noticed on a daily basis in the shop. The same respect and kindness he showed to his customers, he showed to the visiting tennis players.

Values of old came through in the way my father hosted. His view was a simple one: in essence, he was saying to the visitors, if you’ve come all this way from out of town, you must come home to eat with me; you can’t eat in the restaurant or the café, you must come to my home.

Actually, that kindness was a shared, community characteristic. Potch, being a small town, had this small-town generosity and a welcoming way, and nobody espoused these qualities more than my father.

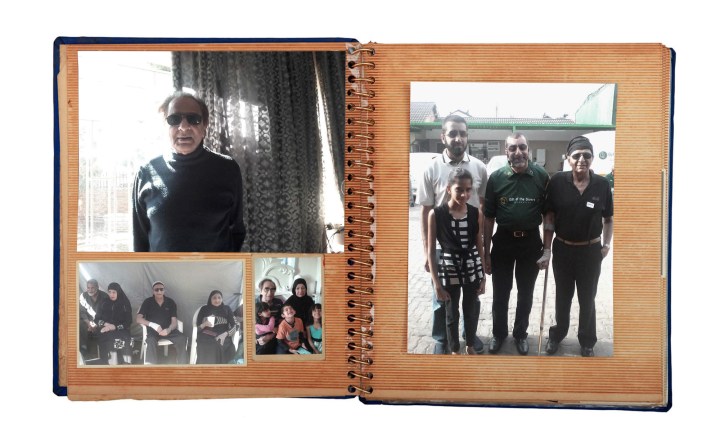

Ismail Sooliman celebrating his 78th birthday on 28 December 2015. He passed on on 21 February 2016. In the picture is Imtiaz’s sister Razina, with family members in the background, at Imtiaz’s house in Potchefstroom. Image: Supplied by Imtiaz Sooliman

Still, on community-mindedness, there were other life lessons I learnt from my father. Here’s another example: in our community, if there was a wedding, the family obviously couldn’t invite everyone in the town but even if you were not invited, you’d go and help the family set up the tables and more. You’d do everything that had to be done, and then you’d leave. It was the same with a funeral; everyone would get involved, supporting the grieving family and their close friends.

Everybody got involved in everybody else’s life, in happy times and in sad times and my dad immersed himself in service to others. In every respect, in every aspect, being part of the community and helping to build community spirit was the key thing that I learnt from my father. He showed me that you should never isolate yourself from the community; you should not be outside of your community. Everything you do is — and should be — about and for your community.

***

My father’s life was rooted in our Islamic faith. And it was he who taught me about our religion, through his words and even more so, through his deeds. He taught me much about the importance of prayer. And the importance of discipline. “You have to be disciplined,” he would say.

Tied to our faith, he taught me other things, such as don’t hurt someone, don’t steal, be good to somebody else’s child. I remember him saying that if the child of someone in your community was doing something wrong, then you should quietly and sensitively tell the parent: “I’m sorry to have to let you know that you need to be aware that your child … (whatever the issue may be) and I think you should take care of your child to ensure this doesn’t develop into a bigger problem.” If you do that kind of thing these days, for example, give a parent a heads-up about something their child is doing – most parents will blow their top. They don’t want to hear you saying something about their child, even if it’s in the child’s best interest, and the parents’ best interests too, to bring the issue to their attention. In the old days, everybody’s children belonged to everybody. So if someone in the community was told something about what their child had done that they shouldn’t have done, nobody got offended.

I realise more and more that many of these old values which my father passed on are absent today. That absence shows how society has changed. We need to bring back those kinds of values by which my father lived his life.

Looking after one’s community was most evident in how my father looked after his family.

First, some context regarding our family: in the old days, we all lived in the same yard; it was an extended family living together in what was a big yard. One brother and his wife lived in one small house; another brother and his wife in another of the houses, and so on. Eventually, when the couples had children and it became too tight and cramped, then some of the brothers and their wives moved out. My father was the one left in the house and it fell to him to look after his father and his mother. When his father — my grandfather — passed away, my father served his mother with dedication, getting her whatever she asked for. He became the one she leaned on; the one she called to when there were needs in the family. For example, my grandmother might say to him, “My son, your sister (or any family member for that matter) is in trouble; she needs your help.”

Extended family gathering. Image: Supplied by Imtiaz Sooliman

Ismail Sooliman and his sister Hajra (who is currently ill), her husband Mamdie (who has passed on), his sister Khatija (who has passed on), his sister Zohra (currently ill), both sisters reside in Imtiaz Sooliman’s hometown, Potchefstroom. Image: Supplied by Imtiaz Sooliman

My father believed, that as per our faith, you needed to look after your parents and siblings until they died, or until the day you yourself died. And he did just that, at a lot of expense to himself. There were many challenges along the way but he had given his mother his word that he would help his siblings and other family members. He did just that, until the day he died, on the 21st of February 2016. He looked after so many family members: his father and mother; he looked after his brothers and sisters; he looked after us, his children. He also took care of my mother from whom he was divorced, up to her passing in 1984, at the age of 42.

When I moved to Durban, he would often call just to check on me. I was sometimes neglectful in calling him; it should have been the other way around. When I got married, he would check on me and my wife, and my children. He would do that with all my siblings, and he did it with all his brothers and sisters. It was really a lesson to learn: how to care. How never to stop caring. I couldn’t have asked for better role modelling. He really did his best as a father, as a brother and as a son.

Dr. Imtiaz Sooliman, Founder of Gift of the Givers Foundation in February 2005. Image: Gallo Images / Sunday Times / Julian Rademeyer)

Dr. Imtiaz Sooliman, Founder of Gift of the Givers foundation with a food hamper for the Poverty Alleviation Feast at Tabankulu in the starving and malnourished Eastern Cape on 29 November 2002. Image: Gallo Images / Sunday Times / Richard Shorey

South African President Jacob Zuma bestows the National Silver Order of Baobab onto Imtiaz Sooliman at the Grand Patron of National Orders ceremony held in Pretoria, South Africa on 27 April 2010. Image: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Liza Hnatowicz

I have to admit that I — on the other hand — have been very neglectful of my children because of the responsibilities I have taken on. I haven’t been able to get it right in terms of bringing my kids up, even from the very start. When they were born, I was already doing my internship in medicine; then I was running a practice trying to provide for my family, and then of course I got involved in Gift of the Givers. It’s been like this for 30 years now, and I’ve spent very little time with my kids. I just haven’t been able to give the same amount of time to them as my father gave to us.

But, it needs to be said that the same values that my father passed on to me, my kids have learnt from me. And of course, they see what I do, and they all want to be with me when that is ever possible.

Imtiaz Sooliman and his son Muhammad Rayhaan, his niece Tasmiyya, his father, Ismail Sooliman, at Gift of the Givers Logistics Centre in Bramley, Johannesburg, around 2015. Image: Supplied by Imtiaz Sooliman

Imtiaz Sooliman of the Gift of Givers organisation on August 9, 2011 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Image: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Nelius Rademan

When my father started his battle with cancer, I got really close to him. I’d fly from Durban to Johannesburg then drive to Potch to see him. Especially in the last two years, he’d keep asking for me to visit. He’d only feel comfortable if I was around him. So I’d often spend six or seven days with him, then I’d drive back to Joburg, fly to Durban, land there, get in the car to head home, and then I’d get a call from him saying that he wanted me back with him. So I’d jump on the plane and go back again. He had lived his life in service to me; I had to drop everything to serve and care for him.

Zohra, Ismail Sooliman’s sister, Sattar (father’s brother who passed on), Mamdie, brother-in-law, who also passed on, his wife Hajra, Ismail Sooliman, his sister Khadija and her husband Ebrahim, (both passed on), and Imtiaz Sooliman’s stepmother Farida at Ismail’s house in Mohadin, Potchefstroom. Image: Supplied by Imtiaz Sooliman

Ismail Sooliman and his brother’s wife, Amina, his sister Zohra, and his brother Sattar (who passed on), visiting him during his illness at the hospital. Image: Supplied by Imtiaz Sooliman

Our religion teaches that one’s parents come first, and one so often hears people say: “Serve your parents now, while you still can.” We have a teaching in Islam that the most unfortunate person is the person who does not serve their parents in their heir old age. For us of the Muslim faith, that is therefore a very important value: care for your parents, always.

In that two-year period of his illness, I spent a lot of time with him. I continued with my Gift of the Givers work but I focused more on seeing to his needs because I knew he didn’t have many more years left to live with us.

What I had learnt from him and had seen in how he had lived his life — in how he had cared for his own family — I was basically putting into practice, and I was giving back to him. It wasn’t something I had to be taught; I’d watched and learnt.

And when you think of the passing down of values, what I learnt from him and put into practice in 2015 and into 2016 when he was dying, my children have learnt from me, and they will pass those learnings on to my grandchildren.

I was fortunate to have a father who taught me so many practical, real-life lessons. He taught me values like not being wasteful, not being extravagant. He taught me how to save money; how to be frugal. He showed me the importance of being a hard worker, and he stressed how important education was and that I should study hard.

And through our days in Potch on the tennis courts, I could see that sport is important in life, and that it is vital to learn to socialise and to mix with many different people, from different walks of life.

The list of positive traits of my father and his kind deeds is so long. He took care of us and never neglected us; he took us out according to what he could afford; he was good to his family, he was good to people; he didn’t get angry; he didn’t drink. He was a wonderful father. I learnt so much from him. DM/ ML

Lessons from My Father is a series of interviews and stories collected and written by Steve Anderson. Anderson has been a high school teacher for 32 years, 26 of them at two schools in East London and the past six at a school in Cape Town where he heads up the Wellness and Development Department and teaches English and Life Orientation. Throughout his career, he has had an interest in the part fathers play in the lives of their children. He says: “This series is not about holding up those who are featured as being ‘The Perfect Father’. It is simply a collection of stories, each told by a son or daughter whose life was, or whose life has been in some way, positively impacted by their father… And it doesn’t take away the significant part played by mothering figures in the shaping of their children. Theirs are the stories of another series!

In case you missed it, also read ‘Be the best version of yourself’ – holding on to what my dad taught me

‘Be the best version of yourself’ – holding on to what my dad taught me

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A man – and his family – to be much admired. Wish there were a lot lot more real people like you in this world. Well done sir!

Lovely tribute, Imtiaz. Condolences on your loss.