RESTITUTION

Saying sorry about slavery — is that sufficient?

It is the eternal struggle between two principles, right and wrong, throughout the world. It is the same spirit that says ‘You toil and work and earn bread, and I'll eat it’. No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation, and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle. — Abraham Lincoln, from the 1858 senatorial election debates with Stephen Douglas

‘Slaves, be obedient to your human masters with fear and trembling, in sincerity of heart, as to Christ.” — New Testament, Ephesians 6:5-8.

Somewhat improbably, slavery is in the news: the Dutch prime minister has apologised for his nation’s role in carrying it out, and the state of California is considering paying reparations to the descendants of enslaved persons. Do such things have meaning for South Africa and South Africans?

Just before Christmas 2022, Mark Rutte made news (probably the first time in many years that a Dutch prime minister has made international headlines) when he offered a formal apology for his country’s “slavery past”.

In so doing, he acknowledged that the legacy of slavery continued to generate “negative effects”, even if the Dutch had officially outlawed slavery in their possessions in 1863. Slavery had ended in the Netherlands itself some years earlier.

In his apology, Rutte said: “For centuries under Dutch state authority, human dignity was violated in the most horrific way possible… And successive Dutch governments after 1863 failed to adequately see and acknowledge that our slavery past continued to have negative effects and still does. For that, I offer the apologies of the Dutch government.”

Rutte offered his thoughts in a speech at the country’s National Archives, in response to the 2021 report, “Chains of the Past”, issued by the Dutch Slavery History Dialogue Group.

“For centuries, the Dutch state and its representatives facilitated, stimulated, preserved, and profited from slavery. For centuries, in the name of the Dutch State, human beings were made into commodities, exploited, and abused,” Rutte went on to say.

He added that slavery must be condemned as a “crime against humanity,” — a view very few would disagree with in our own time — even though it still persists in various forms, in practice, if not with de jure legal protection. Even now, it persists in the shadows in various Western nations, despite its officially illegal status.

Rutte acknowledged he had experienced a personal “change in thinking” about slavery and that he had been wrong to have thought the Netherlands’ role in perpetuating the practice was “a thing of the past.”

In his remarks, Rutte added, “It is true that no one alive now is personally to blame for slavery. But it is also true that the Dutch State, in all its manifestations through history, bears responsibility for the terrible suffering inflicted on enslaved people and their descendants.” Now that is certainly not the kind of public statement one hears routinely from a nation’s leader.

‘Profited greatly’

Discussing this public apologia, CNN noted that the Netherlands had “profited greatly from the slave trade in the 17th and 18th centuries; one of the roles of the Dutch West India Company was to transport slaves from Africa to the Americas. The Dutch didn’t ban slavery in its territories until 1863, though it was illegal in the Netherlands.

“Dutch traders are estimated to have shipped more than half a million enslaved Africans to the Americas, Reuters reports. Many went to Brazil and the Caribbean, while a considerable number of Asians were enslaved in the Dutch East Indies, which is modern Indonesia…”

We should add to that sad litany that the first shipment of 20 enslaved persons from Africa brought to North American soil had been carried by a Dutch-flagged ship. In 1619, the ship’s captain sold his human captives to the English settlers in their new colony of Virginia.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Year 1619, the birth of America’s original sin (and the founding of the nation)

That date has recently provided a name and core idea for the New York Times’ “1619 Project” discussing the legacies of slavery — an effort that has given rise to a growing public debate about the way American history is being presented in schools.

And that, in turn, has merged with an increasingly acrimonious national debate over the ideological values of “critical race theory”, a stalking horse for other political agendas.

New bogeyman: Republican Party wields critical race theory as an election weapon

SA slavery largely ignored

Interestingly, in all the reporting of Rutte’s thoughts on slavery, virtually no media reports — internationally or in South Africa — noted South Africa’s strong historical connection to the fact of that trafficking of enslaved humans by the Dutch.

Queried about it, a Dutch diplomat explained, “I think he started with the communities that are most represented in Dutch society and some of whom are still part of the Kingdom. Their numbers of enslaved are also greatest. Hundreds of thousands. I am sure they will turn to the east and south too, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, South Africa, etc.”

Rutte’s statement also seems to have elided around the truth of the ubiquitousness of slavery historically — beyond that perpetrated by his own nation in the past — as something once found throughout most of the world. That observation could lead one to the question of why more governments (whose nationals and institutions were similarly deeply implicated in the slave trade) have not offered apologias for their roles in condoning, supporting or promoting slavery.

One answer to that may well be that such statements could conceivably open the gates to waves of claims for restitution and reparations on behalf of descendants of all those slaves — or even on behalf of those societies whose members, taken prisoner, had been unable to survive their arduous journeys into captivity. (Historians estimate that perhaps a third of all enslaved persons had died en route to their destinations.)

Meanwhile, British actor Benedict Cumberbatch is now coming under pressure for a personal demonstration of remorse (and presumably reparations) because his ancestors had become wealthy by owning a plantation on Barbados in the West Indies that had used enslaved labour — and was later compensated by the British government when slavery was abolished across the British empire.

Slavery across human history

Of course, slavery was not just something conjured up by the Dutch East and West Indies Companies — or by the other European nations engaged in this practice. As a socioeconomic fact, it stretches back across human history.

There are all those biblical references to slavery, sagas of people taken captive and then forced into lives of slavery, and even the way destitute persons sometimes surrendered themselves into slavery because of unpayable debt.

Greek and Roman classical literature is also replete with discussions and descriptions of slaves and slavery. This even includes the relatively rare individuals who had been slaves but who had then been able to transcend their circumstances in purchasing or gaining freedom because of esteemed service to those who had owned them, or via earnings from their labour elsewhere.

Naturally, the images of slaves (often serving as gladiators) in the Classical world has become a staple of films and novels such as Quo Vadis, Ben Hur, and Spartacus, as well as the more recent cinematic epic, Gladiator. But there have been yet more recent examples of slavery, even after the movement towards its abolition in the 19th century.

Consider the use of slave labour by Germany and Japan during World War 2 (forcing those labourers to build weapons in underground factories or to construct roads and railways through jungle terrain), or the incarcerated millions sentenced to the Soviet prison camps, or all those persons still being trafficked across borders and illegally forced into contemporary versions of slavery as sex workers or indentured labourers in barely reimbursed, unending factory toil.

Back to the Netherlands

But let us circle back to the context of Prime Minister Rutte’s statement.

Forty years ago, this writer visited an exhibition of paintings and artefacts from the rise of the Dutch commercial empire in the 17th and 18th centuries. One of the paintings showed the family of a Dutch merchant stationed on the small Japanese island of Deshima located in the harbour of the city of Nagasaki. Japan’s ruling shogunate had sealed off all foreign access to Japan from the beginning of the 17th century for hundreds of years, save for one trading station on that island, operated by the Dutch East Indies Company (the VOC). The trading station soon became a commercially valuable spot to source such things as porcelain and silk.

In the picture, standing behind the family seated formally on their chairs, in the shadows of the composition, there was the family’s “servant,” a dark-skinned woman with a distinctly Southeast Asian cast to her skin and facial features. That would not have been unusual. Many VOC officials had profitable postings in the VOC’s holdings in territories that were part of the company’s rapidly expanding rule throughout the islands of what became the Dutch East Indies, prior to their assignment to Deshima. And those officials would almost certainly have had indentured individuals or slaves as part of their households.

Over time, that “Dutch seaborne empire” increasingly included trading stations and territories on islands all across the Indonesian archipelago, as well as on the islands of Formosa and Sri Lanka, trading forts in India, control over northeastern Brazil with its prosperous sugar cane plantations, various islands in the Caribbean Sea, the territory of Surinam in South America, the small settlement of what became New York City, and, of course, that refreshment station of Cape Town, as well as forts in West Africa. Those forts were for the purpose of acquiring human captives from surrounding territories, via trade for such things as iron tools, cloth (Javatex, as it came to be called since it imitated Javanese batik), copper wire, and, of course, alcoholic spirits like gin.

But beyond the Dutch presence in West Africa, there were other European slave trading forts along the African coast operated by the French, Spanish, Portuguese, Brandeburgers and Danes, all designed for the purpose of obtaining captives and sending them on to colonial territories — enforced, involuntary, and lifetime labour crucial for the success of plantations and in mines.

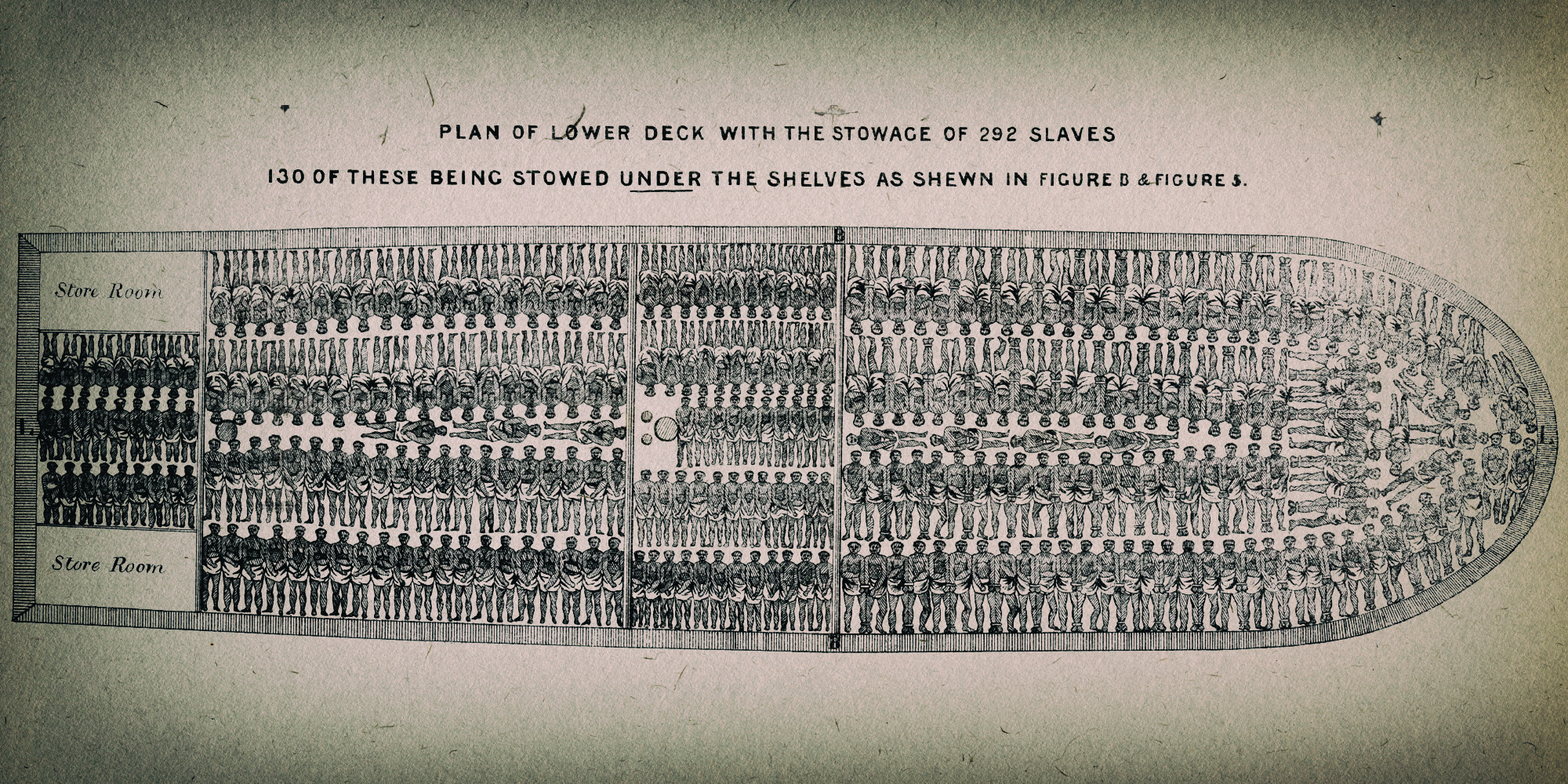

Stowage of a British slave ship, Brookes (1788). (Image: Wikipedia)

There was an unrelenting demand for such labour — ultimately numbered in the millions over several centuries — because enslaved persons had the habit of dying from the brutal treatment they received, from illness and poor nutrition, from punishment inflicted on them for rebellions, or simply from their succumbing to despair over their baleful and unfathomable circumstances.

Meanwhile, over centuries, a growing share of the indigenous populations of the Dutch possessions in the East Indies, most especially on the densely populated island of Java, endured what became a quasi-slavery-style existence without being removed from their homeland.

They were compelled to raise valuable crops such as rice, pepper, and sugarcane for forced delivery to the Dutch at undervalued prices. Moreover, they were also required to provide unpaid corvée labour to build or repair roads, canals, harbours, and other infrastructure. This treatment was not quite slavery, but the difference was often more semantic than real.

Rutte’s confession about the iniquities of slavery might just as easily have been issued in the name of the successor rulers of Spain, Portugal, France, Denmark, England, the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary states along the North African littoral from Morocco to Egypt, Brandenburg, the still more complex case of the Belgian king’s personal control of the Congo River basin, and the governments of the southern half of the United States.

But there is also the legacy of the Omani sultanates strung out all along the East African coast (more on that later). There is also the less often discussed role of African kingdoms which were, themselves, complicit in this trafficking of humanity, as they obtained captives via warfare or through something approaching a trade in human flesh and then sold their captives to the conveyers of those enslaved persons on to their dismal fates elsewhere.

The Cape

To this litany we must now add the enslavement by the Dutch of people from as far afield as Angola, Mozambique, Bengal, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and all across Southeast Asia who were then brought to the Cape and who, over time, together with the surviving original inhabitants of the region — the Khoi-san — gradually became the people now usually referred to as the Coloured people. (That term is now an increasingly contested one, with the word “Camissa” offered in its place. Camissa is the creolised form of ǁkhamis sa, meaning “place of sweet waters,” the Khoi people’s name for Cape Town in Kora, one of the languages of the Cape.) These individuals and their descendants were held in bondage until the end of slavery at the Cape in 1834.

The Byzantines, Ottomans and Russians

Moreover, while some European nations were not part of the African and Southeast Asian networks of capturing persons to enslave them, they nevertheless also had their own histories of human commerce. From early in the existence of those statelets that eventually coalesced into Russia by around the 11th century, the capture and transport of enslaved persons to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople or further to the East was a staple of their commerce.

This was in addition to the more usual traffic of furs, precious metals, timber, and amber. The successor to the Byzantines, the Ottomans, carried on this practice with other conquered peoples such as the Circassians of the Caucasus Mountains region, or from tribes beyond the formal reach of their sovereignty.

Once Moscovy/Russia became a more centralised political system by the 17th century, the legal position of peasant farmers was increasingly circumscribed into legal, lifetime serfdom in which labour was owed to nobility and landowners and where their status became hereditary. Eventually, this ran counter to a tendency across much of Europe in curtailing peasant serfdom, especially in areas controlled by the Napoleonic system by the beginning of the 19th century. Russian serfs were legally released from their hereditary status in 1863, but, for many, their real circumstances changed very little.

The Americas

In the Americas, while many of the new republics abolished slavery following their independence from Spain, and even after Haiti’s successful slave revolt against the French in the beginning of the 19th century, the circumstances for the enslaved (or formerly enslaved) on the Caribbean islands that continued as colonial possessions remained bleak.

In Brazil, moreover, where more captives had been transported to than any other place in the hemisphere, legal slavery was only abolished in 1888, over half a century after the country itself had become independent from Portugal. After emancipation, however, the circumstances of Brazil’s black inhabitants did not magically change for the better, as most black Brazilians continued to remain poor and landless.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the extension of slavery into new territories (and then the possibility of the institution being abolished entirely) became the proximate cause of the American Civil War that ran from 1861 to 1865.

This past New Year’s Day marked the 160th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s “Emancipation Proclamation.” This presidential decree said slavery in those states in revolt was now over, even though there was as yet little ability to enforce this until the territory of the Confederate states came under the control of federal troops. It was not until the passage of the 13th amendment to the constitution that slavery as a whole was abolished in national law.

As President Joe Biden said the other day in his commemoration of Abraham Lincoln’s announcement, “The Emancipation Proclamation became an inspiration to thousands of Americans who celebrated all across the Nation that New Year’s Day long into the night. Afterwards, every Union victory became a greater sign that justice could conquer injustice, that freedom would triumph over bondage, and that the battle cry of our Nation was freedom and justice for all.”

Of course, the struggle for actual equality remains incompletely achieved, and there remain shadowy areas where conditions are not much different from indentured servitude. These include individuals trafficked into illegal working conditions from outside the country, or even legally incarcerated persons who, at least in Louisiana, are dispatched on work parties where the prisoners receive no compensation for their labours.

Restitution

This brief, bleak survey of the history of enslavement leads us on to the question of how or what kind of restitution is now possible, given there are no individuals alive now who were specifically and individually victims of state-sanctioned formal slavery.

But wait a minute: there is this astonishing story. A half-decade ago, the very prestigious (and very exclusive and expensive) Georgetown University came face-to-face with the deeply uncomfortable realisation that their institution had been complicit in selling over 200 enslaved persons from the school’s farm in Eastern Maryland on to the far more brutal sugarcane plantation landscape of Louisiana. The funds thus raised had staved off the school’s imminent bankruptcy.

Confronted with this deep moral dilemma about the school’s history, and in the face of genealogists who had been tracking down the descendants of those slaves, the school’s management has been wrestling with how to make restitution to the actual, identified descendants of those former slaves and the university’s behaviour.

Now there are efforts on the part of at least one US state to move towards a form of reparations to individuals who can show direct descent from previously enslaved persons.

As the New York Times reported late last year, “In the two years since nationwide social justice protests followed the murder of George Floyd, California has undertaken the nation’s most sweeping effort yet to explore some concrete restitution to Black citizens to address the enduring economic effects of slavery and racism.

“A nine-member Reparations Task Force has spent months travelling across California to learn about the generational effects of racist policies and actions. The group, formed by legislation signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2020, is scheduled to release a report to lawmakers in Sacramento next year [2023] outlining recommendations for state-level reparations.”

The report went on to say, “While the creation of the task force is a bold first step, much remains unclear about whether lawmakers will ultimately throw their political weight behind reparations proposals that will require vast financial resources from the state.”

Whether or not any such a plan ultimately is adopted by California — or by any other states — the question remains of how far such a movement for restitution or reparations could extend to the larger African diaspora, or others taken into involuntary servitude elsewhere (as in the case of South Africans, the descendants of the entire population of slaves officially manumitted in 1834).

How would such a broad international movement be managed? Who would pay for it from among all the nations involved in the slave trade, and who would qualify? And what should or can be done about any complicity of African states which had sold captives to those who had transported slaves to their destinations from West and East Africa, even as some of their own populations were being similarly treated?

Mozambique, 1910

I want to offer one final personal observation. A dozen years ago, I was contracted by an international humanitarian relief agency to go to the far northern part of Mozambique to document the devastating impact of a series of massive tropical storms. I travelled overland from the regional capital of Nampula to the small city of Angoche, located on the Mozambique coast.

Beyond the storm damage, the town had also suffered from the depredations of a long-running civil war. Once there, however, I discovered Angoche had also been a slave entrepôt — run by a branch of the Omani trading families that had, until the late 19th century, ruled Zanzibar.

A shocker was that it had been the Portuguese colonial army that attacked and conquered Angoche from its Arab rulers in order to end that traffic in humans — in 1910. Presumably the last fighting to end the international slave trade based in Africa.

Portugal, of course, was the same nation that had forcibly transported hundreds of thousands of people on to their agonies in Brazil or to plantations on some of the islands in the Atlantic. They, the Portuguese, certainly had not participated in those naval patrols by Britain and the US that had acted against the slave trade, along the West African coast in the 1830s, 40s, and 50s.

Ending slavery in all its manifold forms was (and remains) a moral imperative, just as the vociferous anti-slavery campaigner, William Wilberforce, had asserted to the British parliament over 200 years ago, saying of his conviction, “So enormous, so dreadful, so irremediable did the [slave] trade’s wickedness appear that my own mind was completely made up for abolition. Let the consequences be what they would: I from this time determined that I would never rest until I had effected its abolition.”

Nonetheless, dealing with slavery’s aftereffects and the generational impacts on the African diaspora — and the places their ancestors had been forcibly wrenched from — remains contested space. Even now. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A very balanced, well researched and thought-provoking article on the many-headed, reaching back deep into pre-history, involving as victims and beneficiaries alternately, so many parts of our globe.

And why stop at slavery? Surely the “slavery” of women in the home and their role often as little more than vassals of husbands and other males was no less pernicious?

The best, I feel, we can do is to try to prevent the worst practices of the past being repeated into the future; we are all, individually, and collectively as societies, on a continuum, to becoming better peoples and citizens. It is called progress.

A detailed article for sure restricted only by the size of the article only.

Acknowledgement of the slave trade from the beginning of time has to be acknowledged for the crime against humanity it was.

The history of the world is full of conquests of nations and the resultant enslavement of the conquered by the conquerors.

The calculation of reparation and to be paid by whom is impossible along with the determination of the source of payment, by whom.

The tribal leadership, dictators and the like that rounded up their own folk for sale as slaves cannot be ignored, particularly in Africa. Kingdoms were built on the slave trade.

Colonials did not simply run around the continent rounding up folk for enslavement.

Acknowledgement of the slave trade throughout time is essential.

An apology is debateable. Determination of reparation is a fools errand because the determination of the starting point in history is problematic.

Who pays?

Are the living responsible or accountable for the actions of those that have passed?

Are the incidents of genocide and their architects not part of the equation?

The same can be said of the architects of wars that caused death and suffering.

How can reparation be calculated?

Will the Arabic nations also be making an apology and offering reparations?

And, as Gregory says, the descendants of the chiefs that sold their own people and those they captured?

Surely there must be a thorough analysis of the historic and causal chain of slavery that can be referred to as an authoritative source of information rather than superficial political posturing?

Europe and the US continue to exploit Africa and the the developing world with their overvalued currencies, another form of slavery?

Very thought provoking! Trying to put slavery into perspective becomes an ever-widening quicksand. One extreme would be nation states as far back as 3500 BC that used brutality to round people to be placed in forced servitude. Another may be opportunity servitude, anyone that, due to government failure, is deprived from the resources and opportunity needed to realise the value they attribute to their labour. Has slavery been abolished – or just become a ‘fatal alternative’?

Who then is [not] guilty?

Asia too was not averse to slavery; China on pretty much all non Han people, Japan on Koreans and even the British (think Bridge on the River Kwai), the Indian caste system that made slaves of the majority of Indians and not just the Untouchables. Slavery swept in waves the World over; all of us were once serfs in various guises until steps were taken – as with the Magna Carta in England – to begin to break the chains that bind and secure, by generally painfully long processes, voting rights for many, with voting rights for women bringing up the rear.

Africa sadly having done the least, over the millennia to advance human rights for it’s peoples, with the result that Africa still lags behind.

Right. I think that I will sue the English for invading Wales! I will claim my little patch of soggy turf in Treharris, up in the valley!

I know I’m pretty darn cross with the Roman’s. What to do?

Rutte has truly opened a can of worms with his statement. Slavery, as vile as it was (still is maybe) has been documented far back in history, so far back that it’s origins are unknown. Also more than half of the various populations on the planet were enslaved at some point, so where do you start with paying reparations. I think Rutte’s got this wrong and he may have a heck of a time trying to convince his taxpayers that they are going to pay compensation to people they’ve never heard of for something that happened long before they were born.

Can I sue the ANC government of illegally accusing me of supporting apartheid because I am white?

How can one be accused of a crime when they were not born when it was committed?

What a lovely ‘can of worms’ and example of the idiocy that soon appears in our best efforts at wokeness! And while we’re having fun: where do I submit my claim for restitution for the lacl of education for women and shall I submit a request to the Pope for restitution of land lost outside Strassbourg, to the Catholics?! I think my descendants and I will be better served if I focus my energy and efforts somewhere else.