Given the history of the ANC’s utter mismanagement of our power grid, and that the party itself has said that load shedding costs it votes, this problem again reveals the limits of President Cyril Ramaphosa’s real power and his ability to manage the country.

It may be all but forgotten now, but it was with the appointment of the current board of Eskom that Ramaphosa first revealed the political power he had gained through his victory at Nasrec in 2017. He was still deputy president, with Jacob Zuma as president in January 2018. Anoj Singh and Matshela Koko were still at the power utility.

With one move, Ramaphosa showed that he was boss. In a statement, he appointed a new board and instructed it to remove executives accused of corruption, including Koko and Singh.

It was the first open display of Ramaphosa’s political power, and it set the scene for the recall and removal of Zuma on Valentine’s Day a month later.

That demonstrated Ramaphosa’s power – but how times have changed.

It appears Eskom has once again revealed the president’s political power reserve – and how little there is of it these days.

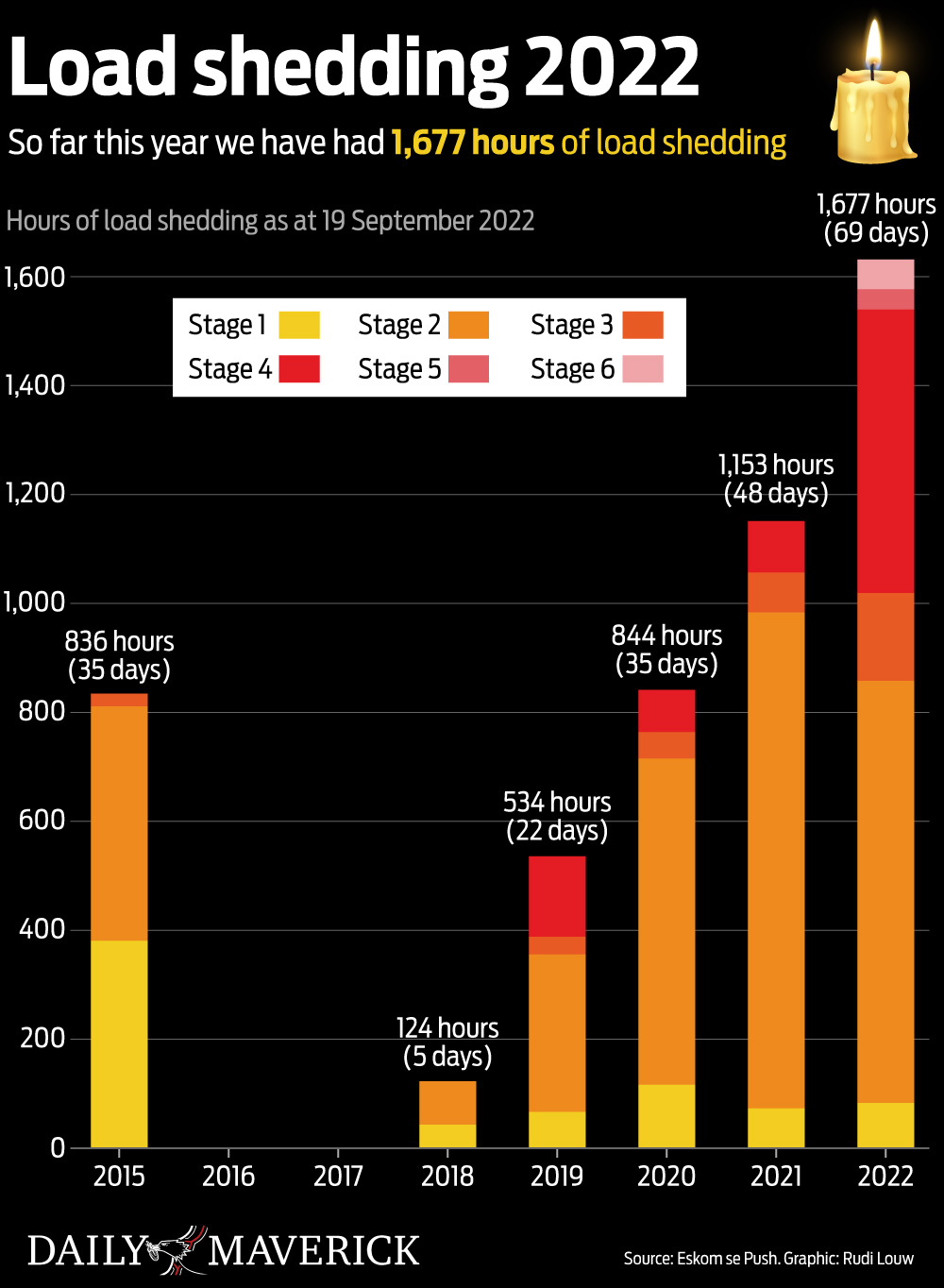

Despite a series of promises, Ramaphosa has simply not been able to ensure a proper supply of electricity for the country. As long ago as 2015, he promised, while still deputy president, that “in another 18 months to two years” we could forget about load shedding.

The situation at Eskom is complicated. As has been said many times by many people, no history of Eskom would be complete without remembering the 1998 Electricity White Paper that predicted load shedding in 2007; the detailed testimony and the findings against Brian Molefe, Koko, McKinsey and others who looted Eskom; and then the other problems it currently faces.

This includes the perception that Eskom is virtually under attack from all quarters.

There are gangs who steal diesel from power stations, unions which Eskom says use violence and threats against workers who refuse to go on strike, and then, the unbelievable levels of corruption within the utility itself.

At one point, the Special Investigating Unit recommended that 5,500 people who work at Eskom should be referred for disciplinary action. That’s a staggering number for an organisations with a total staff complement of about 42,000.

But, as Ferial Haffajee noted on these pages after another intense bout of load shedding two full years ago, “load shedding is like an X-ray revealing the weaknesses of Ramaphosa’s presidency and his inability to deliver on his promises, no matter how well meaning his intentions”.

And this is his biggest problem – the fact that he made promises he has failed to keep.

Get updates, analysis and guides to understanding and surviving the power cuts – all in one place

The same is true for Eskom’s CEO, André de Ruyter. He has faced huge opposition from many quarters.

Some questioned his real experience as someone who once worked in the coal sector for Sasol and then as CEO for Nampak. Organisations like the Black Business Council have repeatedly called for him to go, with suggestions that it was not appropriate for a white man to be appointed to this post in the first place.

His defenders have suggested that at least some of the opposition to his presence is motivated by those who want to continue their corruption.

But again, De Ruyter’s real problem is the promises that he, too, has made to end the rolling blackouts.

There are many other people who bear responsibility, and yet appear to receive less blame for what is happening:

- Deputy President David Mabuza is technically in charge of an energy “war room” to deal with the crisis. There is literally no evidence to suggest that he has made any contribution whatsoever to fixing the problem.

- Gwede Mantashe is the Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources. His critics have regularly accused him of failing to make it easier for new power to be added to the grid. He is also in charge of the various processes that are supposed to help that happen.

The CEO of Business Leadership SA and Eskom board member Busisiwe Mavuso wrote in Business Day on Monday that “had the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme not been stalled by corrupt political interests from 2015 to 2019, the energy plants from bid window 5 would have been operational and SA would have had half the load shedding last year”.

That is a stinging criticism.

But Mantashe has consistently defended himself, saying that he cannot allow a failure in the electricity market, and that to rely on renewable energy sources (which can be built in two years, compared with coal and nuclear which take around a decade) would be a colossal mistake. And he continues to campaign for nuclear energy despite the fact that power from a new nuclear facility would not flow before 2035.

[embed]https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-09-19-rolling-blackouts-six-stages-of-eskom-induced-grief-and-pain/[/embed]

To be clear, nuclear power is not something with which you should take short cuts.

Then there is Pravin Gordhan, the Minister of Public Enterprises, a portfolio that has political authority over Eskom itself. He has remained largely quiet, and tends to only speak on these issues at moments of gravest crisis.

What is clear from this mixture of political interests, characters and intrigue, is that this system and the people in it are simply not working. If they were, the lights would not be going out with such deadly regularity.

What makes this more astounding is that there is important evidence that load shedding costs the governing party votes. The party’s deputy Secretary General, Jessie Duarte, before she died, said exactly that: that one of the reasons for the party’s poor showing in last year’s local elections was the intense load shedding in the days before the polls.

If the ANC was focused on winning in 2024, and if its government was able to fix the problems created by Eskom, they would presumably do so.

The fact it has failed to do this perhaps suggests that both the ANC and its government simply do not have the capacity to resolve these problems.

During the last bout of Stage 6 blackouts, Ramaphosa eventually made a series of announcements suggesting that the private sector would be playing a bigger role in the provision of electricity. While these reforms were generally welcomed, it was not clear why it had taken so long for him to act, and to make these changes.

At least one person who is working with the Presidency on these issues, Professor Sampson Mamphweli, has suggested that people will see the results of these reforms in the next 18 months to two years. He remains adamant that change is coming.

Those who will be running the ANC’s election campaign may well be hoping that he is right.

Because, if he is not, it is entirely likely that load shedding – and the ANC’s complete and sustained failure to deal with Eskom – is what loses it the 2024 election. DM

Power lines in Johannesburg, South Africa, 10 November 2021. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Kim Ludbrook)

Power lines in Johannesburg, South Africa, 10 November 2021. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Kim Ludbrook)