FREEDOM DAY REFLECTION

Molo Songololo still fights for children’s rights 28 years after doing its bit for section 28 of the Constitution

From the police officer handling a stolen car report to a radio talk show host, Molo Songololo’s work with children and teenagers and its iconic magazine have made an impact — and continues to do so.

‘It’s the 50-cent books we were waiting for. It was a real programme of democracy, teaching us our rights: I am a person, I am protected,” recalls radio host Lester Kiewit of the Molo Songololo magazine that he helped distribute at the Kannemeyer Primary School in Grassy Park, Cape Town.

But it’s the three-day 1997 trip to Robben Island with creative arts workshops and final-night performances that remains in his memory as a “most magical experience”. Part of a children and democracy programme, the children came from the Cape Flats, townships and also from wealthy suburbs like Llandudno and Scarborough.

Twenty-five years after that outing as a 13-year-old, the memories remain vivid. It’s the impact Molo Songololo has.

The young person-centred approach to empowerment and awareness and facilitating children to express themselves about what affects them continues today.

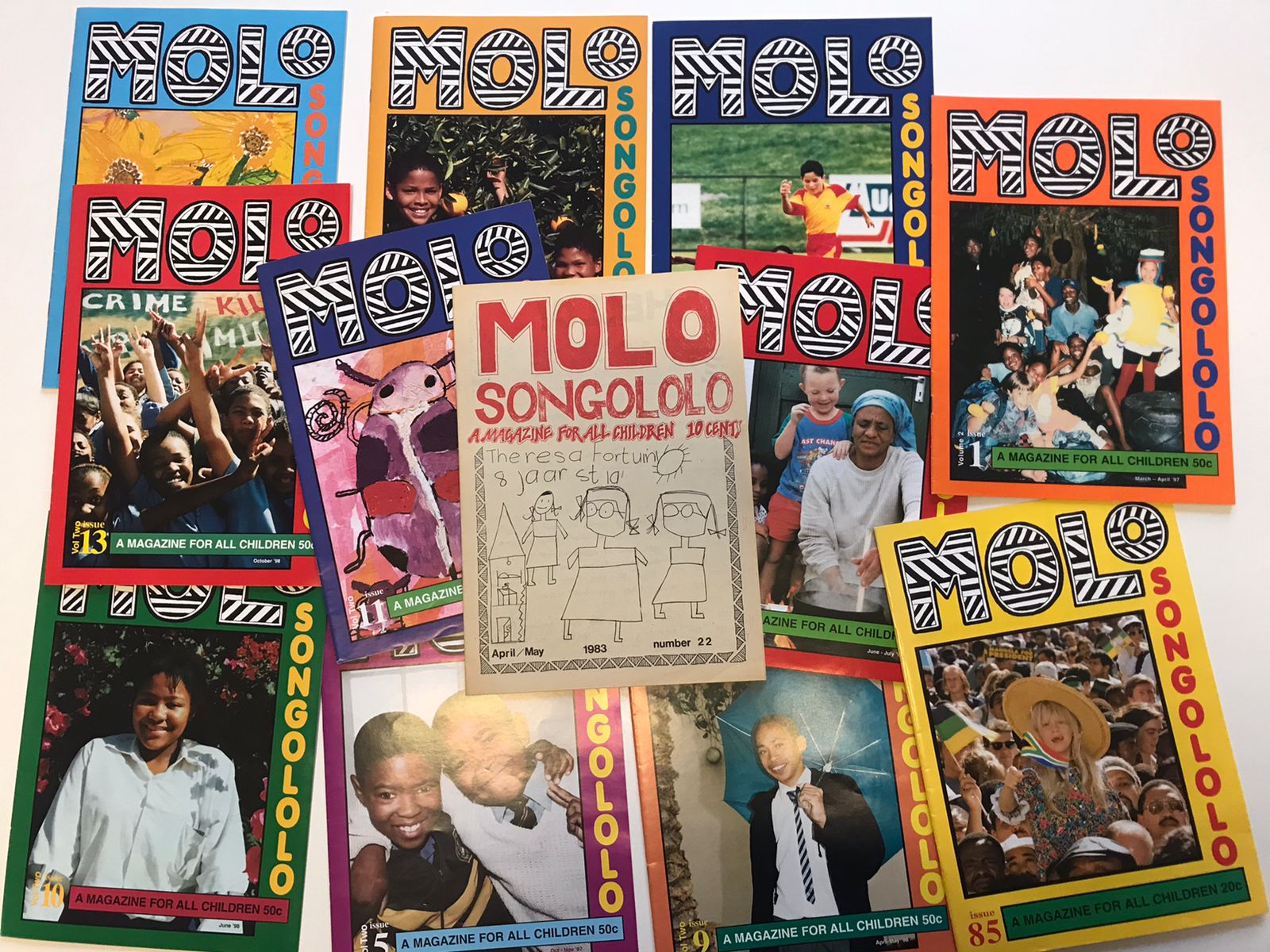

‘It’s the 50-cent books we were waiting for. It was a real programme of democracy, teaching us our rights: I am a person, I am protected,’ recalls radio host Lester Kiewit of the ‘Molo Songololo’ magazine that he helped distribute at the Kannemeyer Primary School in Grassy Park, Cape Town. (Photo: Supplied)

On 6 April, Molo Songololo was the South African participant in the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights global consultations — led by two presenters selected by peers after a series of workshops.

The United Nations entity was canvassing children’s views on sustainable development, from social progress to climate, for what’s called a general comment, or a detailed guide for governments and other organisations to better implement rights.

This is part of the child and youth empowerment work — and facilitating children expressing themselves on issues affecting them — that Molo Songololo does alongside advocacy, child protection and victim empowerment.

Attorney Noluthando Xolilizwe is deputy chairperson of the Molo Songololo board because of the impact of exposure to children’s rights education and awareness she had at the age of 14 while in high school.

“I remember Molo had a magazine; we got to experience other children’s stories and upbringing… I remember us going to Parliament, where we presented our views,” says Xolilizwe. “I always wanted to remain part of that and Molo.”

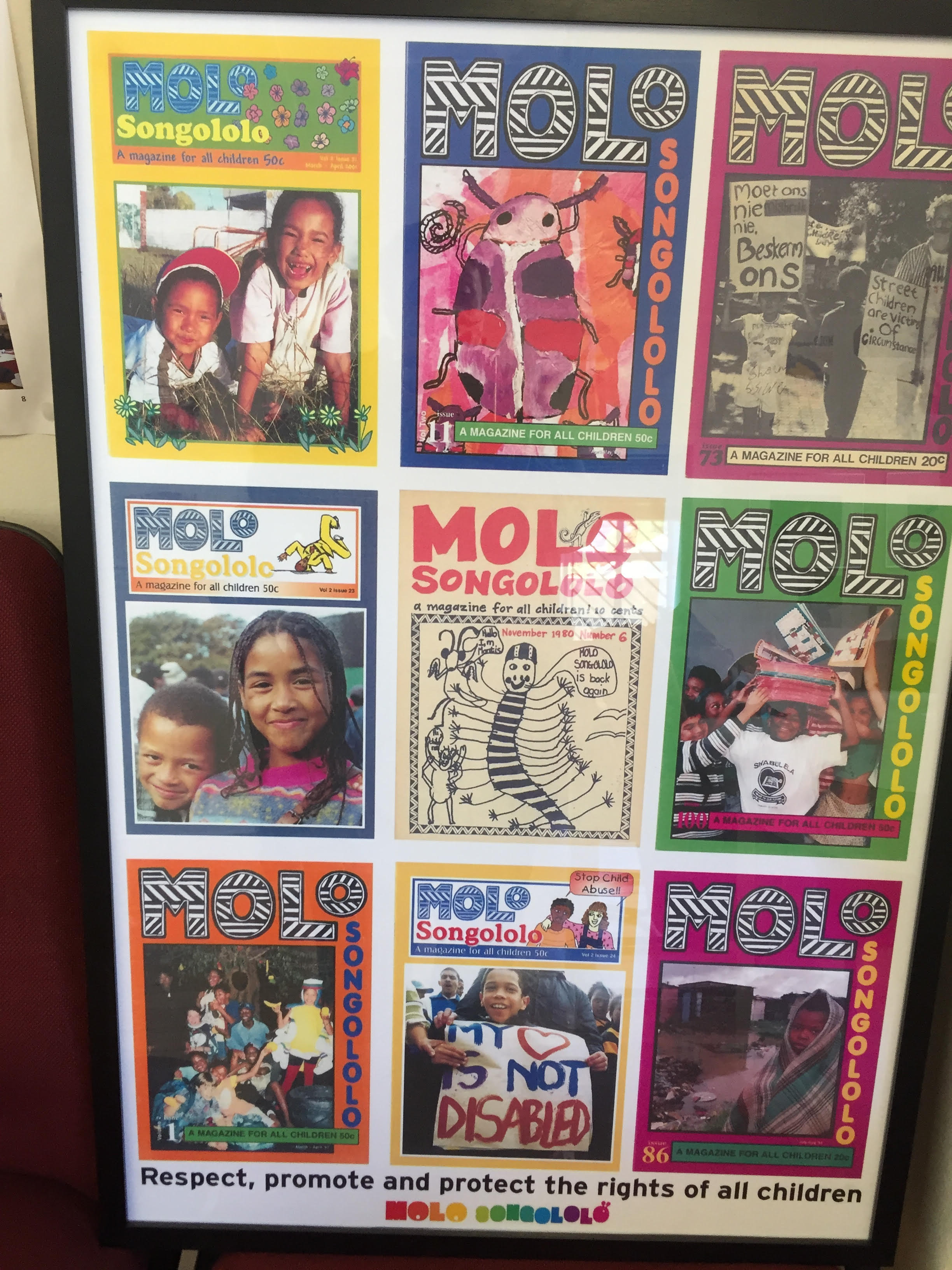

The iconic Molo Songololo magazine folded in 2005. It was one of the funding squeezes the child rights organisation had to face in its 42 years. Another came in 2010 when staff remained at reduced salaries.

“We stayed. It was a tough few months,” says Melda Davids, who 21 years ago worked as a cleaner at Molo Songololo. Today she’s the office manager at Molo Songololo’s headquarters in Cape Town — other branches are in Atlantis, Delft and Beaufort West — and is also a go-to person in her community because of the work she does at the child rights organisation.

“I want to be here to assist the children. I have a passion [for] working with children; that made me work here.”

Covid-19 restrictions

The Covid-19 lockdown has aggravated the situation of children. Already at overwhelming risk of hunger, gangsterism and joblessness, the pandemic restrictions disrupted schooling and increased hunger as school feeding schemes stalled.

Six out of 10 children went hungry, according to a July 2020 Statistics South Africa report using data from the 2015 living conditions survey. The 2020 Child Gauge showed that 30% of children live below the poverty line in households unable to meet nutrition needs, and malnutrition means one in four children is stunted.

One of the consequences of the Covid-19 lockdown disruptions appears to be a rise in opportunistic and transactional sexual activities, made even trickier as South Africa’s widespread conservative outlook often means sex and related issues are not discussed.

“Most of the time the young person doesn’t know they have rights. We find parents themselves have gone through a similar experience and many have not received counselling. That’s why we also work with parents,” says Molo Songololo’s executive director, Patric Solomons.

“We started doing this work because no one else did it.”

In 2020, Molo Songololo worked with children predominantly aged between 12 and 17, mostly girls, according to the annual report, with some 44% of the children deemed at risk. Four out of 10 are also survivors of rape.

As an essential service, Molo Songololo continued during the Covid-19 lockdown restrictions to deliver trauma counselling, victim support, empowerment and awareness workshops once that was again possible — peer learning is important — and continued its Dignity for Girls project, which provides a three-month supply of toiletries and sanitary products.

“They don’t have the basics. Most girls live in homes with high unemployment,” says Solomons of the project, which started years ago.

“Feminine hygiene is more than sanitary pads. Being able to wash one’s hair with nice-smelling shampoo is important to how a young person feels about themselves.”

It’s the “from the ground up” and child-centred approach Molo Songololo takes, given its roots in South Africa’s Struggle activism.

‘I remember Molo had a magazine; we got to experience other children’s stories and upbringing… I remember us going to Parliament, where we presented our views,’ says Attorney Noluthando Xolilizwe. ‘I always wanted to remain part of that and Molo’. (Photo: Supplied)

The United Nations 1979 Year of the Child kick-started a community-based initiative to promote children’s rights and to have children articulate themselves, which then became Molo Songololo.

From 1980, the Molo Songololo magazine allowed children to tell their stories to other children, promoted diversity and informed children about their rights. As Solomons recalls, one edition was confiscated because it explained what to do when police fired tear gas, which regularly happened across South Africa’s townships in the 1980s.

Other work included linking up with the 1980s Free The Children campaign — the apartheid government jailed children. This collaborative and partnership approach remains today with cooperation with government departments and other nonprofit organisations.

By the early 1990s, as South Africa headed towards the transition to democracy and the first democratic elections of 27 April 1994, Molo Songololo was a founding member of the National Children’s Rights Committee and helped facilitate children to draft the 1992 Children’s Charter. That, and enabling children to make submissions to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and to the Constitution drafting process is recognised in the April 2009 report by the Presidency and Unicef’s joint situational analysis on South Africa’s children.

Today, section 28 of the Constitution’s Bill of Rights guarantees children the right to a name and nationality from birth, to family care and to basic nutrition, shelter, healthcare and social services alongside protection from maltreatment, neglect, abuse, degradation and exploitative labour practices.

As legislation was being drafted to give effect to these rights in a democratic South Africa, Molo Songololo’s work shifted to child rights and protection advocacy. A key focus became fighting and ending child and human trafficking and sexual exploitation.

Some of this work was practical, like researching child trafficking cases such as “Amien’s girls”, a Cape gang-related prostitution and kidnapping racket in 2000. Or not mincing its words in one of its regular parliamentary submissions when Molo Songololo spoke up in May 2002 against the then safety and security minister, Charles Nqakula’s parliamentary reply that child and human trafficking wasn’t prevalent.

Commissioner for Children

In the past decade, in addition to this anti-trafficking work, child protection and accountability projects unfolded. This included Molo Songololo facilitating the participation of 740 children in the process of the June 2020 appointment of a Western Cape Commissioner for Children.

When Molo Songololo co-founder Zurayah Abass died of cancer at the age of 50 in September 2003, Solomons stayed on. He doesn’t like talking about himself.

“I became interested in why people are being treated differently,” he says of growing up, before returning to Molo Songololo’s work.

“Many of the children we work with do not drop out of school. People are seeking out our help, saying: ‘So and so told us to call Molo’,” he says. “We would like to increase capacity because the need is so great out there. And, hopefully, help more children, families and communities.”

The impact of his work at Molo Songololo often emerges at unusual times and places — when a domestic worker recognises him during a visit to her workplace or when a police officer arrives following a stolen car report. Responses are warm, recalling how Molo Songololo’s child rights work had made an impact on their lives.

“I got to be friends with Patric Solomons on a personal and social level,” says Kiewit, who is a patron of the Children’s Radio Foundation. “I’m very, very proud of that. To be a Molo kid.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

MOLO SONGOLOLO is 1 of the achievements of the new South Africa!!! Patric Solomons and the organization do sterling work. I had the privilege to attend their workshops (Wonder if SAPS still send police officers to their courses). Debbie (who now works in America) was impressed with my knowledge of human trafficking and child matters and at 1 of their classes in Atlantis, I was asked to give a class. I still have fond memories of that occasion. My impression is that the police are failing if they don’t send members on a regular basis to Molo Songololo’s courses.