South Africa

Selling Apartheid: New book lays bare extent of South Africa’s propaganda war

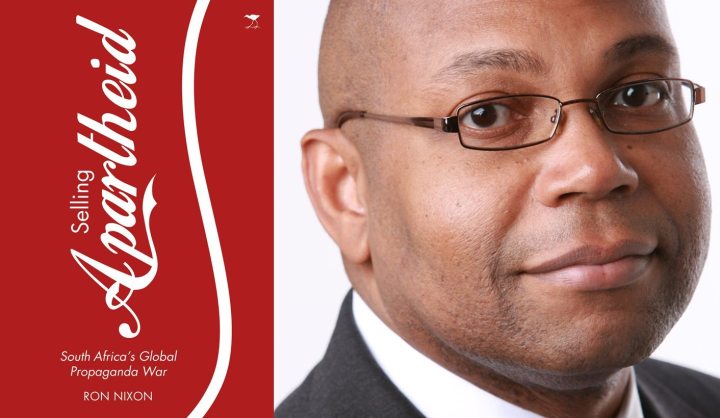

At its height, the Apartheid government was running one of the most expensive international propaganda campaigns the world has ever known. Pivotal to this were a number of black Americans, paid by the South African government to lobby in the US to try to win support for Apartheid. Journalist Ron Nixon’s new book Selling Apartheid: South Africa’s Global Propaganda War tells the fascinating story of a regime desperate to get the international community on side. By REBECCA DAVIS.

When journalist Ron Nixon was growing up as a young black child in the US, his grandmother gave him a magazine about South Africa. Page after page, it featured images of wonderful wild animals, sunsets, happy black people on the beach.

“I thought, ‘What a place!’” Nixon recalled to the Daily Maverick on Thursday. “Wow, I want to go there!”

Decades later, Nixon would realise what neither he nor his grandmother had at the time. The magazine was a piece of propaganda produced by the Apartheid government’s Department of Intelligence, one of countless such publications distributed internationally under the guise of being ‘regular’ magazines. It was only while researching his new book, Selling Apartheid, that Nixon came upon it again in his home.

“It was on my shelf all along!” he marvels.

To understand the scope of the propaganda war into which Nixon’s childhood magazine fitted, picture this scene: The setting is a boardroom in 1970s South Africa under the presidency of John Vorster. There, a group of bureaucrats have gathered to hear the results of a survey undertaken by an expensive New York public relations firm. The firm has been tasked with finding out what people internationally think of Apartheid South Africa – and what the bureaucrats hear isn’t pretty. They are informed that South Africa is the most unpopular country in the world, with the sole exception of Idi Amin-led Uganda. The country is “less favourably regarded” than both the Soviet Union and China, they are told.

This, Nixon writes, was one of the moments that saw South Africa’s propaganda war step up a gear.

From the earliest days of Apartheid in the late 1940s, DF Malan’s government sought to win US support, in particular, by convincing Americans that a white minority government in South Africa was a critical bulwark against continent-wide communism. But the world being what it was at that time, Nixon notes that “there was actually little need for a sophisticated (Apartheid) propaganda apparatus aimed at the great powers”. Racial segregation in the US had de facto been abolished but was effectively still the reality, while European powers maintained their colonial rule over much of Africa.

Amid growing international criticism, however, under Malan’s successor JG Strijdom Apartheid’s propaganda machine was refined and professionalised. Public revulsion towards the Sharpeville massacre saw the need for pro-Apartheid material to be pumped out at speed. The Hamilton Wright Organisation, a public relations firm with experience representing unpopular governments, was called in. It produced articles and films featuring beaming black South Africans and scenic wildlife, and distributed them worldwide.

It was under then information minister Connie Mulder in the 70s that South Africa’s propaganda efforts picked up serious steam. Mulder told prime minister Vorster that what South Africa needed was a campaign that would “buy, bribe, or bluff its way into the hearts and minds of the world”. One of the biggest thorns in Pretoria’s side, Nixon writes, was the rise of black legislators in US politics. Mulder hired a former journalist called Eschel Rhoodie to counter the negative perception of South Africa spreading worldwide, and Rhoodie was given access to a secret fund of millions.

It was Rhoodie who hired the expensive New York public relations firm to undertake the survey which delivered such devastating results as to South Africa’s global popularity. From this realisation came the action plan that would see the infamous founding of The Citizen, as a newspaper to counter left-leaning papers like the Rand Daily Mail.

Mulder, Rhoodie and Vorster would eventually be brought down in the scandal known as Muldergate. “More than anything,” writes Nixon, “the scandal would destroy the widely held popular opinion that while Apartheid-era leaders supported a harsh and repressive policy which denied blacks their rights, they personally weren’t corrupt or out to enrich themselves.”

Vorster’s toppling did not see the end of the propaganda war. Although his successor PW Botha would disband the Department of Information and create a replacement department, Botha retained as many as 60 of the secret projects spearheaded by Rhoodie.

The reach of the government’s information tentacles was impressive. In the UK, two MPs in the ruling Labour party were on the Apartheid payroll, writes Nixon. They were tasked with lobbying for Apartheid in the House of Commons, and spying on anti-Apartheid groups. German journalists were taken on annual trips to South Africa. A group was formed in Japan to establish links with Japanese unions. An Argentinian advertising expert was hired to flood South American papers with pro-South African articles. There were abandoned plans to create and bankroll a pro-apartheid Norwegian political party.

In the 80s in the UK, lobbying was handled by a firm called Strategy Network International (SNI), which campaigned to prevent sanctions being implemented against South Africa, and which would treat UK politicians to trips to South Africa to persuade them that things weren’t all that bad. SNI was “paid and given its instructions” through a company set up by one Sean Cleary. Nixon records that Cleary was later revealed as an agent of the South African intelligence services. (Cleary was also the speaker at a sustainability conference in Cape Town which I attended in 2012, where he was presented without reference to these aspects of his past, and gave a talk on “integrity”.)

The bulk of the Apartheid government’s efforts, however, were directed at the US. Nixon’s book is populated with extraordinary characters, and perhaps particularly those black Americans who became such diligent mouthpieces for the Apartheid government. Nixon’s previous short e-book Operation Blackwash vividly chronicled the Apartheid regime’s attempts to win the favour of African Americans, and in Selling Apartheid Nixon does not neglect this surreal aspect of the propaganda war.

We are introduced to characters like Max Yergan, a black American who lived in South Africa for many years, became a confidante to African National Congress (ANC) pioneers such as Govan Mbeki and AB Xuma, returned to the US to lobby for the rights of black South Africans alongside the likes of WEB du Bois – and abruptly transformed into someone who would go on to inform on his political comrades to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and tour South Africa warning about the evils of communism. In 1953, Yergan gave an interview to an American magazine suggesting that “the South African government deserved the world’s understanding, rather than scorn, for its policy of apartheid”.

Then there was George Schuyler, whose trajectory mirrored Yergan’s. A black American, Schuyler was a vocal advocate of black South African rights until he became, like Yergan, vehemently anti-communist. Writes Nixon: “In the late 1940s, Schuyler began to shift his political views, perhaps because of an awareness that he had come under suspicion by American intelligence agencies like the FBI.” By the 1960s, Schuyler was giving radio interviews voicing views like: “I don’t think it’s the business of other people to change (Apartheid) society”.

Andrew T Hatcher, Richard Nixon’s deputy press secretary and “one of the most high-profile African Americans in the world”, set up lobbying trips to South Africa for black American journalists and legislators where their movements were strictly controlled. Hatcher was also paid by the Apartheid regime to make press appearances on American television to tell the US of the ‘encouraging’ situation in South Africa. He also allegedly distributed lapel pins with interlocking American and Transkei flags, Nixon writes, to suggest the degree to which the US backed the puppet ‘homeland’.

William Keyes, another black American, was paid $400,000 a year by the Apartheid government to write editorials in conservative newspapers attacking the “communist” ANC. In a CNN interview in 1985, he spoke of the need to recognise “the reality of the ANC as a terrorist outlaw organisation which has perpetrated violence primarily against innocent black people”.

Nixon’s book also contains fascinating nuggets about behind-the-scenes wrangling over sanctions. Nixon records that Margaret Thatcher’s steadfastness to avoid sanctions against Apartheid was unmoved even by a plea from the Queen herself. “Royal advisers took the unusual step of leaking to the (Sunday Times) newspaper the monarch’s political views and the growing distance between her and the prime minister over South Africa,” Nixon writes.

“Unstinting support” was also given to the apartheid government by US televangelists such as Jimmy Swaggart and Jerry Falwell, with Falwell even encouraging “millions of Christians to buy Krugerrands” to support the South African economy. Much of the US opposition to sanctions was premised on two pillars: (a) the line that sanctions would hurt black South Africans more than whites; and (b) the need to keep South Africa strong to prevent communism from sweeping the continent.

“I hate communism more than I hate apartheid,” Nixon quotes one conservative black American minister as saying; apparently a fairly common sentiment.

In the late 80s, the government’s propaganda efforts moved away from attempts to defend apartheid towards focusing on smearing the ANC via communism. Even up to apartheid’s last gasp, the propaganda machine was still whirring. “While president FW de Klerk freed Nelson Mandela and lifted the ban on the ANC and other anti-Apartheid movements in February 1990, his government also continued to fund secret propaganda projects aimed at undermining the ANC and Mandela,” Nixon writes. It took up to 1992 for South Africa to stop selling apartheid.

Nixon concludes that if the propaganda war actually achieved anything, it was to delay the inevitable. Over the phone, he elaborates: “I think they got taken.” He means the lobbyists who went to work for the Apartheid government charged often astronomical sums with very little to show for it in the end.

Perhaps the book’s most haunting aspect is in its detailing of those black Americans who collaborated with Apartheid’s regime; in this respect, it recalls Jacob Dlamini’s Askari. For Nixon, though, what it comes down to is something murky and not clear-cut.

“For the most part what I hope it shows is the complexity of all these movements,” he says. “That they are not as black and white as it seems.” DM

Ron Nixon’s Selling Apartheid: South Africa’s Global Propaganda War is published by Jacana.

Read more:

- A chronicle of Apartheid’s propaganda war on black America, in the Daily Maverick

Become an Insider

Become an Insider