The story of fatherhood is rarely straightforward. This collection brings together inspiring, humorous, and at times heartbreaking accounts that reveal its contradictions, complexities and enduring impact. The book grew out of a much-loved series first published in Daily Maverick, with new stories added to deepen and expand the portrait of fathers and their legacies. Together, these narratives reflect South Africa’s wider social landscape while calling for new ways of building connection and care. Here is an excerpt from Joanne Hichens’ essay, “Everyone has a story”.

***

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Jos-dad-with-Dalai-Lama.jpeg)

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Joanne-portrait.jpeg)

An old leather object rests in a forgotten corner of my office; my father’s dumpy briefcase. It’s broad and wide enough to have fitted into it the numerous files and important papers he carried with him to work, and back again, every day of his 40 years as a career diplomat.

The leather is dull now. In my father’s lifetime it was polished. The brass combination lock is tarnished and stuck on the numbers 333. March 1933, the day of my father’s birth.

Alan McAllister Harvey joined the South African Department of Foreign Affairs in 1957, when he was 24 years old. For decades, he was a National Party man. He had, or so I believe, joined much in the way young men of a certain era – perhaps in a misplaced desire for freedom, or adventure – ran off to join the Foreign Legion. Perhaps he wanted to escape the sadness of his home, the death of one brother, the institutionalisation of another. I don’t think, in all honesty, he cared much for politics.

I still remember pressing my ear to an empty glass against the wall – to amplify the conversation – that separated my childhood bedroom from my parents’ room. My mother felt he wasn’t progressing quickly enough through the ranks of the Foreign Service. He was, after all, a rooinek – he didn’t have the advantage of being an Afrikaner.

My mother’s father, Senator Jasper Daniel Rossouw, possibly a Broederbonder, had wanted a son to follow in his footsteps, but he got my mother instead. She didn’t do too badly. She was the first woman at Stellenbosch University to graduate with a law degree. She and my father sat together in class. He was 16, she 17. They fell in love and never parted. When my father joined the Foreign Service, she left her legal-aid job to become the woman behind the man. She had more ambition than my father, would egg him on, coach him. She wanted for him – perhaps more than he did – that elusive promotion to the rank of ambassador.

I saw a side to my father, even as a child, that was more curious than ambitious, more kind than ruthless; soft-spoken for the most part, he cultivated humility.

I dust off the case. I haven’t looked at the contents in a long time, but I know that I’ve stored inside a selection of photos and documents that remind me of the essence of my father.

I pull out a certificate, my father’s appointment as head of mission to New Zealand signed by Elizabeth R, and under the flourish is printed: “ELIZABETH THE SECOND, by the Grace of God, Queen of New Zealand and Her Other Realms and Territories, head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith.”

And here’s a photo of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, with my daughters flanking him, all three of them, arm in arm, serendipitously dressed in shades of maroon and pink.

Proud of his family, my father took us along, as children and as adults, to official gatherings. He’d introduce us to all and sundry.

He encouraged the art of conversation. Of finding common ground. He and the Arch would bump into each other at the doctor’s rooms, where they’d joke about their prostate cancer.

In this briefcase too, I find a letter granting my father the Keys to the City of San Antonio, Texas; and a memorial service programme for the victims of flight SA295, the Helderberg, which went down in the waters off Mauritius; there’s a certificate of service from the Philippines government for whom my father was, in his retirement, the honorary consul, issuing visas and repatriating, in coffins, with official papers, those sailors who’d died on ships before docking at Cape Town harbour. There is also a photograph of my father cuddling a koala bear in his arms, the bear’s paws held tight around my father’s neck.

But it is the three images, side by side on my desk now, that mean the most to me.

The first is a framed photo of my father with the Dalai Lama. My father is in his usual black suit, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, the “Ocean of Wisdom”, wearing his uniform of purple robes, a gold section over his shoulder. They are clasping hands, my father’s hand and the Dalai Lama’s in a tight embrace, an authentic connection between the two men.

In another photograph, my father is with his Holiness Pope John Paul II on an official visit in 1995. Again my father is dressed in a dark suit and tie; the pope, surrounded by his entourage, is in white robes, a gold cross around his neck. And again, the men – leaning into each other, pictured in a moment of tête-à-tête conversation – clasp hands; my father’s fingers, I see, as I look closer, are square-tipped and precisely manicured. The very hands, the warm hands, I used to hold.

And then there’s a photo of President Nelson Rolihlahla “Pulling the Branch of a Tree” Mandela – in a suit and silver tie for the pomp of this occasion – and my parents in their finery, all three of them standing close, smiling, Mandela’s crow’s feet crinkling into a genuine grin of delight. This was the night of the inauguration of the president and the executive deputy presidents of the Republic of South Africa at the Amphitheatre of the Union Buildings, Pretoria, on 10 May 1994. Mandela, after everything he’d been through and survived, is youthful, spry. My father, too, stands tall.

I pull out a fancy menu for the dinner held after the presidential address: springbok paté en [croûte], smoked trout and king prawns, lamb ragout, bobotie with yellow rice, a selection of venison and pickled tongue. With all cultures catered for, the menu includes a halaal and kosher selection.

Picking up the photograph, I see, as I turn it over, an envelope taped to the back of the frame. Folded inside are newspaper clippings, cut from various sources, on Mandela’s death. In my father’s spidery print, with a trembling hand – he was 80 by this stage – on the envelope, is written: “MADIBA 5.12.2013”. And I remember how my father’s eyes misted on that day.

My father’s stint as consul general in New Zealand wasn’t entirely successful. There was trouble over rugby. His car was pelted with eggs and tomatoes. He then went on to Taipei as head of mission, indeed as ambassador. South Africa was, at that time, a supporter of the Democratic Republic of Taiwan.

My mother learnt to paint lilies in watercolour class, and my father collected snuff bottles. I own them now, each intricately delicate, each treasured by my father.

He was intensely interested in the cultural heritage of China, particularly the Cultural Revolution, and how the island museums were caretakers of so much of the past. I remember, too, being in a back alley with my father, watching as he downed a cup of freshly drawn snake blood, good for the heart. My father was willing to try anything, to learn.

His most important years, though, were the years he worked for the ANC government, appointed as Nelson Mandela’s chief of protocol after the ’94 elections. He was required to meet every dignitary arriving in South Africa. He advised Mandela on the do’s and don’ts of particular visitors, how low to bow to the Japanese, and how, when the Chinese toast Ganbei!, one downs the contents of one’s glass. He organised award ceremonies, and the delivering of credentials at televised events. He ensured proper decorum and understanding and dignity, between heads of state. He and Mandela dressed for these particular occasions in coat-tails, as required, respectful of whomever was the latest guest, whether a head of mission from the US, or from the island nation of the Seychelles, the smallest country in the Africa region.

I learnt from my father about the Vienna Convention of 1961, which reaffirms the principle that sovereign states are considered equal in international law, regardless of their size or power or differences.

My father learnt that people, as equals, can work together for change; people themselves can change, people can forgive, and be forgiven; and learn to love.

Whether you were the pope or the Dalai Lama or Mandela, or the neighbour who came for afternoon tea, or the hospice nurse who cared for my mother in illness, or the handyman who chatted about his family – a guy called Denis who did odd jobs around the house – my father, interested in those around him, would engage. Intensely curious about people, he’d assert: “Everyone has a story.”

I pack the documents and photographs back in the briefcase, thinking of the virtues we uphold, including the right to freedom of expression. In a world where violence is the norm – in a world of hypocrisy, cruelty, of persecution, of racism, of genocide – it is the humble tolerance of these revered leaders, pictured so affectionately with my beloved father – the Dalai Lama, the pope, Nelson Mandela (and Tutu also, with my daughters), with their varying beliefs and statuses, their oftentimes controversial or difficult stories – that becomes the lesson I choose to share, the lesson I learnt from my father. DM

Joanne Hichens is an author. Her books include Death and the After Parties and Divine Justice.

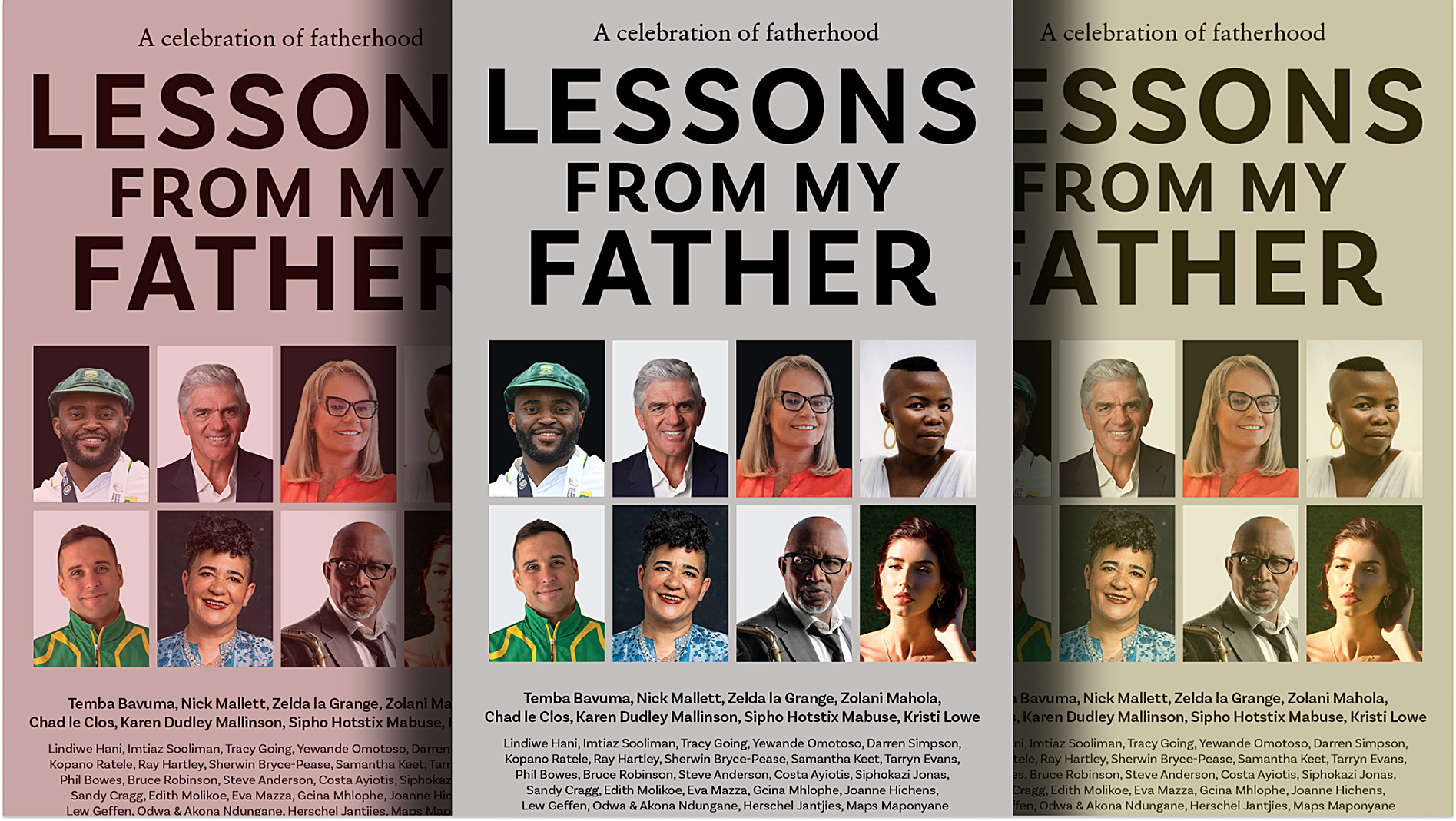

Lessons from My Father, compiled and edited by Melinda Ferguson and Steve Anderson, is published by Melinda Ferguson Books. The book is available at a retail price of R340.

Lessons from my Father is a collection of essays compiled and edited by Melinda Ferguson and Steve Anderson. Many of the essays are drawn from the Daily Maverick series Lessons from my Father.

Lessons from my Father is a collection of essays compiled and edited by Melinda Ferguson and Steve Anderson. Many of the essays are drawn from the Daily Maverick series Lessons from my Father.