It is almost an iron rule of democratic politics that when the cost of living increases dramatically, the party in power will come under pressure and it will more often than not pay a price for it.

Some historians like to point out that the French Revolution in 1789 occurred partly as a response to rising bread prices. (... and a short supply of cakes - Ed)

More recent history has shown the impact that the rising cost of living and associated lower living standards can have in democracies.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Elections 2024

In the years after the Global Financial Crisis from 2008, many European voters were attracted to populism.

In the United States, the fact that many people feared their children’s lives would be worse than their own, and that life expectancy for white males declined for the first time outside of war, almost certainly contributed to the election of Donald Trump as president in 2016.

The country probably most similar to us in structure and inequality, Brazil, also experienced its version of this. A very populist Jair Bolsanaro was elected president after a difficult economic period.

(Intriguingly, a very popular former president who had served two terms made a historic political comeback, and was elected president again.)

In South Africa, the impact of the rising cost of living in a short space of time has been intense.

First came the pandemic, then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As a result, some figures now indicate that by just next year, 49% of South Africans will be going to bed hungry or suffer from severe food insecurity.

Chillingly, the percentage of children who receive so little food they are now stunted has dramatically increased. Around seven million children are growing up in homes below the food poverty line.

That’s 7,000,000 children.

In our country.

All of this shows how strong one political message from uMkhonto we Sizwe could be; that life was better under Zuma than it was under Ramaphosa.

Muted response

And yet, strangely, there has been no impactful response to this from most of our political parties.

It would be rational to expect in these crazy days that there would be a sizeable move to some flavour of populism from most of our political players, and that in fact they would compete with one another to make the most radical promises.

However, among those who make the real decisions, there appears to be no appetite for addressing the cost of living issues substantively. Instead, strangely, things are almost going the other way.

Instead of promises to ease monetary policy, the National Treasury is even wondering aloud if it should reduce the SA Reserve Bank’s inflation target. This would require interest rates to be kept higher for longer.

Amazingly, this is being considered just months before a very difficult election.

Also, from the political centre, there is no demand for a massive Basic Income Grant, or real increases in other social grants.

Of course, it is true that the Social Relief of Distress Grant has recently moved from R350 to R370/a month, but this doesn’t even make up the losses for inflation since it was first instituted four years ago.

Almost the only movement from what could be called the political centre on this issue comes, strangely, from Action SA. This party, led by a former chairman of the Free Market Foundation, is promising a BIG of R780 a month, which would increase over time.

All of this would appear to leave the radical playing field to other parties, the biggest of which of course is the EFF.

It has promised to simply double social grants if elected into office.

And while the EFF may increase its share of the vote in this election, that is not yet certain.

If the EFF does not win significantly more votes, and if parties that do not promise big increases continue to dominate, this might put to bed once and for all the debate over whether receiving social grants does influence voting behaviour.

The fact that opposition parties appear to almost ignore the cost-of-living crisis appears to fly in the face of all democratic norms.

But there may be important reasons for this.

The first is that real-life solutions to our set of crises are difficult to find. To improve the lives of our people would require a comprehensive set of interventions, many of which would be opposed by many vested interests.

There are important reasons why our economy is still so concentrated, and why so many people have been able to ensure their children can use the system to succeed, while so many others have been left behind.

To find solutions to these problems is difficult, and perhaps beyond many of the people who manage our political parties (this is not so much a comment on the leaders of our parties, but rather on the depth of our problems).

This makes it difficult for any party to promise solutions that would appeal to a diverse set of people.

Again, the fact the EFF is so radical proves this, it can espouse its ideology precisely because it is not chasing the votes of a diverse group, but rather a much narrower sliver.

Second, it is likely that voters are very well aware of the very nature of our society. They know any immediate solutions for their hardship will be difficult to come by.

Adversarial tactics preferred

As a result, they may be very wary of trusting any particular party that comes with a blockbuster set of solutions.

This may explain the cry of so many people around braais and dinner tables, they don’t know who to vote for, because “none of them can be trusted”.

This means it is much easier for parties to instead focus on other issues.

They may believe it is a better use of airtime and resources to scare voters into voting for them than in finding a positive economic message of their own.

Again, like in other democracies, there is nothing unique in this. Many parties in many places appear to spend much of their time attacking their opponents, rather than concentrating on their own positive message.

This may have made Barack Obama’s “Yes We Can” slogan so rare and powerful, it was a deliberately positive message that did not concentrate on his opponent (it is also a huge contrast to the situation in the US now, where Trump and Biden are basically telling voters only they can stop their opponent).

Unfortunately, unless something unexpected and dramatic happens in this election, or in future polls, there is likely to be very little political incentive for parties to change their tune. There simply won’t be votes in a positive economic message.

And thus, despite the incredible hardships our people are experiencing, the cost of living may remain fairly low on the campaign agenda. DM

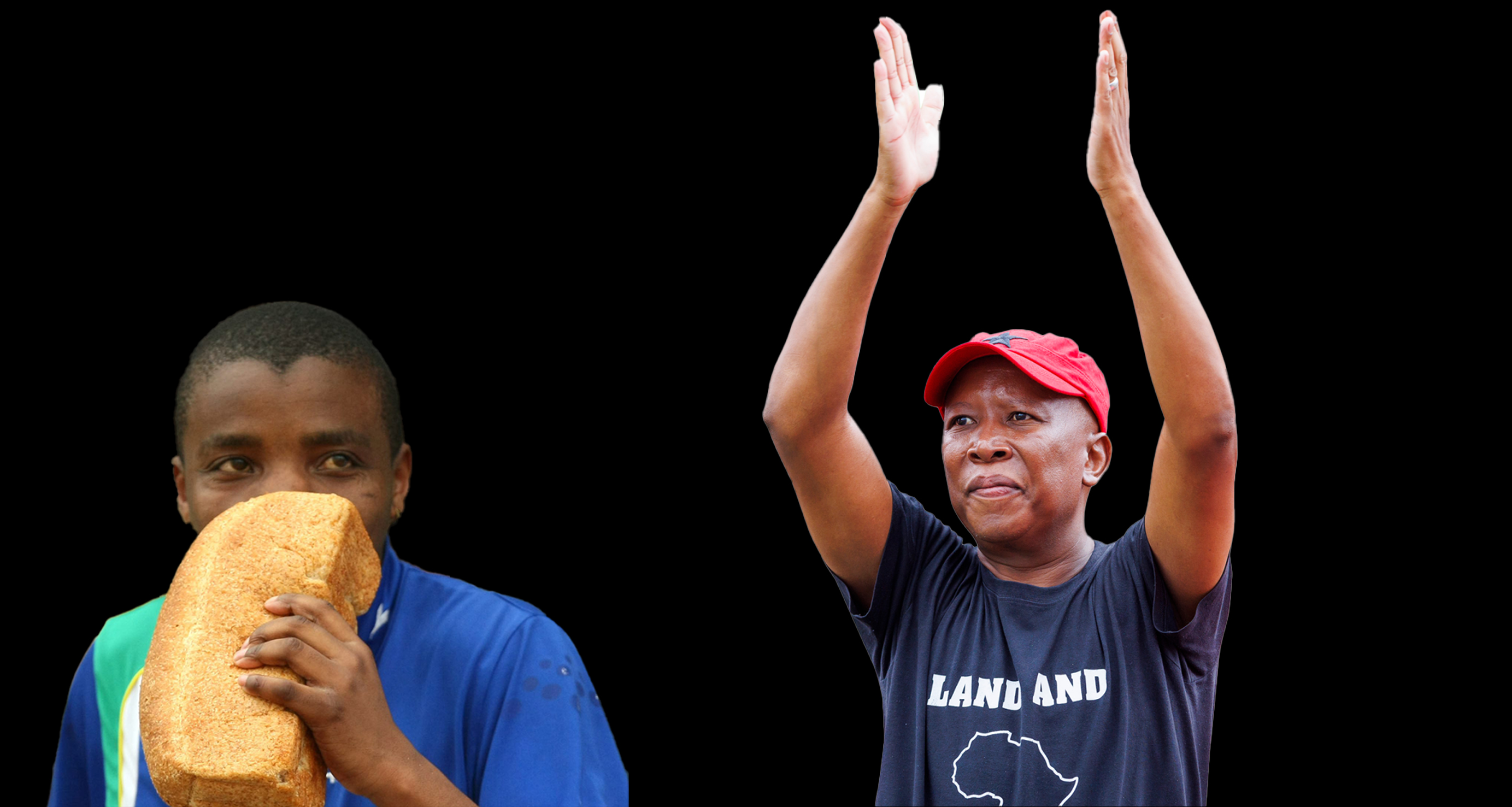

Illustrative image, from left: A soccer fan with a loaf of bread. (Photo: Anesh Debiky / Gallo Images) | EFF leader Julius Malema. (Photo: Gallo Images / Dirk Kotze)

Illustrative image, from left: A soccer fan with a loaf of bread. (Photo: Anesh Debiky / Gallo Images) | EFF leader Julius Malema. (Photo: Gallo Images / Dirk Kotze)