GEOPOLITICAL RELATIONS ANALYSIS

X factor — winds of change are blowing in 2024 as voters worldwide prepare for polls

This year, of the many elections taking place, there will be major interest in the results of polls in Mexico, South Korea, India and South Africa. There is also the little matter of what may become a ‘hinge of history’ election in the US in November.

In Russia’s recent presidential election, Vladimir Putin won with a remarkable 87.29% of the votes. Notwithstanding that great achievement, it is unlikely Putin will ever surpass one election in North Korea where one of the Kims, the country’s hereditary dictators, reportedly garnered 102% of the votes.

Of course, in Putin’s realm, to have opposed his re-election was an almost certain ticket to oblivion. Little opposition was allowed at the polls, although there were two virtually unknown candidates who were not expected to make much of an impression.

The one man who — in an alternate universe — might conceivably have been a significant challenger, Alexei Navalny, died suddenly shortly ahead of the election, reportedly from a cerebral stroke. This followed his reported leisurely outdoor stroll at the penal colony where he had been held, in the midst of Siberia’s winter.

Of course, in this year of elections, there have already been several other polls — with dozens more due to follow. And so we should turn our attention to the elections where actual candidates have been vying for the love and affection of the populace — and the right to govern their respective societies.

Political movements and influences in these elections are varied. They may be inspired by ethnic/racial/religious identitarian movements, desires for a more democratic order, populist anger and fear, or anger over the governors’ perceived ineptitude or driven by economic, kitchen table issues. Or they can be a combination of some or all of these motivations.

Importantly, too, in some cases, the results of elections can affect national directions and policies. We’ll get to that in the case of the US-South African relationship.

Important elections in Senegal and Indonesia have already taken place with a degree of transparency and fairness that would be unbelievable in many other countries.

In the vast island nation of Indonesia, retired general Prabowo Subianto, despite a tainted human rights record from his years as a military figure in the Indonesian province of New Guinea and during his country’s occupation of Timor-Leste, scored his win largely by appealing to a very young population seized by his campaign’s use of popular culture and their hopes for economic growth and greater prosperity.

Supporters paid little attention to the candidate’s past, let alone the awkward fact his father had been the late former president Suharto, a man who had had significant deficiencies in the human rights and corruption sweepstakes. Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim nation, has globally important mineral reserves and is located across one of the world’s most important trade routes.

In Senegal, meanwhile, after ructions and protests over an on, off, on again election, that country’s poll finally happened and incumbent president Macky Sall was replaced by Bassirou Diomaye Faye. Faye was newly released from prison and ran successfully on an economic reform, anti-corruption platform.

Then, in Turkey, although it was not a national presidential election, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s party suffered an embarrassing beating in municipal elections in the country’s big cities like Istanbul and its capital of Ankara. Significant dissatisfaction over near-hyperinflation and punishing interest rates appears to have made the difference, more than any more generalised anger over the increasingly repressive political climate.

Looking to the immediate future, there will be major interest in the results of national elections in Mexico, South Korea, India and South Africa. There is also the little matter of what may become a “hinge of history” election in the US in November.

In some electoral contests, the choice may be more about which candidate makes the voters’ collective gorge rise the least. Even so, we should keep in mind that democracy is the form of government people have quite literally died for in their efforts to have it gain a footing in their nations. And sometimes, too, citizens have fought to protect an existing system from being destroyed by those who would replace it with some form of authoritarianism or totalitarianism.

Any progress towards a more democratic world must be applauded, and any erosion of it must be denounced — especially given the theory of a domino effect from the collapse of democratic practice in one nation influencing developments in neighbouring nations.

Supporters of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) during a rally in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India, 31 March 2024. (Photo: Prakash Singh / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

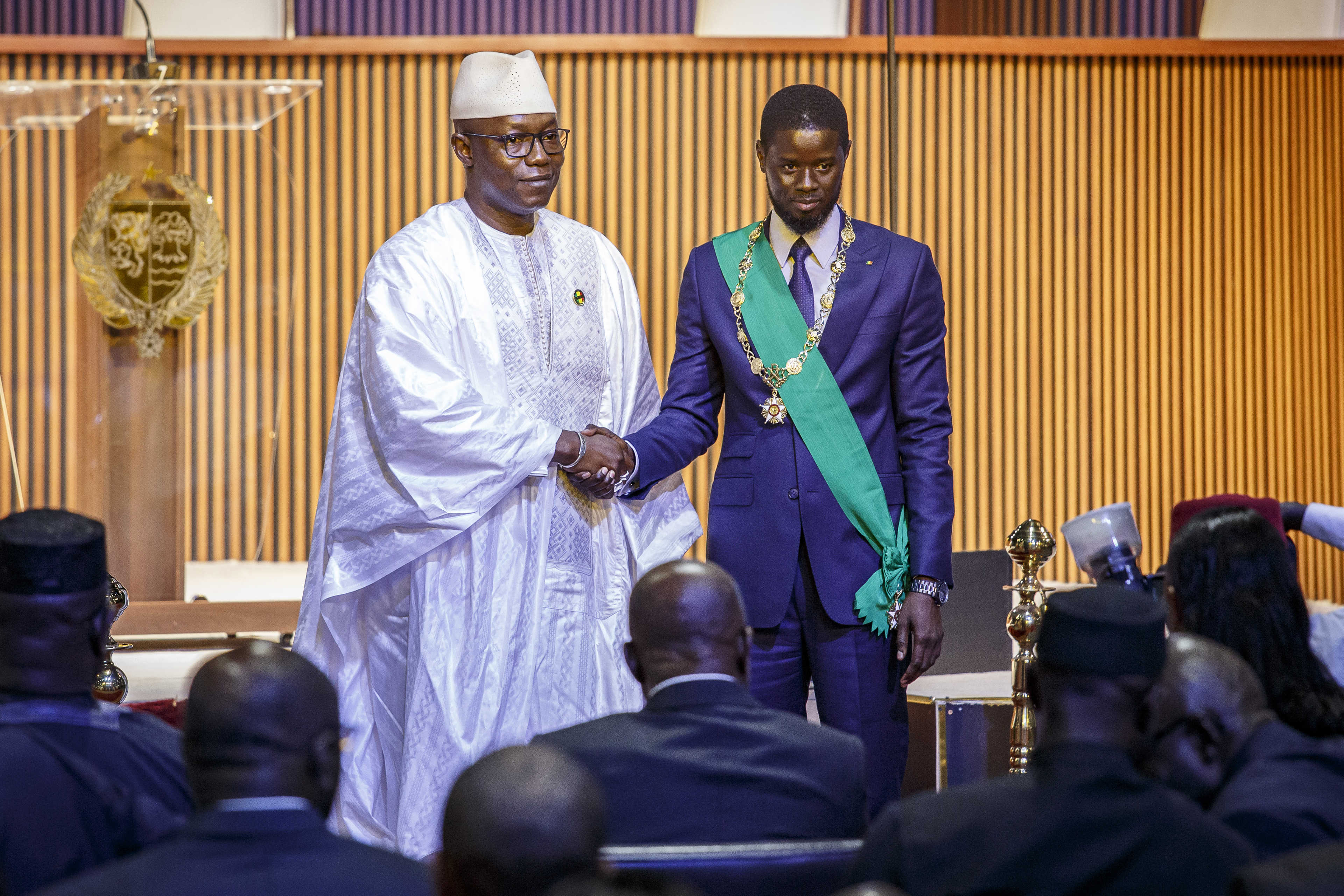

Bassirou Diomaye Faye, Senegal’s president (right), greets Malick Diaw, president of Mali’s transitional council, during Faye’s inauguration ceremony in Diamniadio, Senegal, on 2 April 2024. (Photo: Annika Hammerschlag / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Three important polls

Of all the upcoming contests this year, the ones that probably concern us most are in South Africa, India and the United States. In the first of these, the African National Congress has governed since the apartheid era, but is now facing serious challenges from multiple political directions and may well lose its majority status.

India’s election, which begins on 19 April and runs for six weeks, will be a major measuring stick of the political life in the world’s largest democracy, as religious/ethnic tensions have made things difficult in several parts of that vast nation.

Incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya National Party, the BNP, remain the favourite to score a decisive victory, despite charges that the BNP’s policies promote a divisive ideology of ethnic Hindu nationalism.

And, of course, the US’s political stability faces serious identitarian-populist challenges from former president Donald Trump. Trump is a man who in his own words would be a dictator for a day, and who, more broadly, has been carrying out a campaign that has tapped into the darkest recesses of the country’s political life. Fears of immigration and crime, and wild conspiracies about the so-called deep state have been integral to much of Trump’s appeal.

Predicting the outcome of South Africa’s polls is best left to other analysts at Daily Maverick, especially given that polling data coming in is all over the landscape.

Former US president Donald Trump during a campaign event in Green Bay, Wisconsin, US, 2 April 2024. (Photo: Daniel Steinle / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The US political contest

Turning to the US’s ongoing presidential race, it is now clear the two leading candidates will be incumbent President Joe Biden and Trump, barring unforeseen developments. Both men have secured sufficient delegates through voting in the primaries to become their parties’ candidates at the national conventions in July and August.

Yes, there will be a sprinkling of third and fourth-party candidates such as independent candidate Robert F Kennedy Jr, the Green Party’s Dr Jill Stein and leftist academic Cornel West. These parties and candidates will be on the ballots in many states. But, while they may, collectively, gain sufficient votes in some states where the race is particularly tight to have an impact on the winner in those states, none of those individuals will become president on 20 January 2025.

Both leading candidates face significant challenges in their campaigns. For Biden, the dance he has engaged in over his administration’s policy vis-à-vis the Israeli military campaign in Gaza is continuing to alienate demonstrable numbers of his electoral coalition, even as his policies have generated major economic growth, low unemployment and job growth that seem to be under-appreciated. And many believe he is not strong enough on the immigration issue.

Meanwhile, as The Economist has noted, “Donald Trump’s legal woes deepened as three judges rejected attempts to dismiss criminal cases against him. A federal judge denied the former president’s request to toss out a criminal case about his alleged hoarding of classified documents. Another judge rejected Mr Trump’s attempt to have an election interference case dismissed on First Amendment grounds. A day earlier a judge in Manhattan declined to throw out charges brought in a ‘hush money’ case.”

The Trump strategy seems to be the weaponising of his legal troubles as the spear point of his campaign.

Presidential Candidate Robert F Kennedy Jr makes a campaign announcement at a press conference on 9 October 2023 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Kennedy announced he will end his Democratic primary bid and will run for president as an independent. (Photo: Jessica Kourkounis / Getty Images)

US-South Africa relations

This election trajectory leads us to the question of what the incoming administration will have in store for US-South African relations in 2025. While changes in a country’s national leadership are often not enormously important in the nation’s foreign relations as elections are usually fought over domestic policies, sometimes such a leadership change can have very real impacts.

During the first two years of his term of office, the Biden Bible in foreign affairs was one of enhancing stability and an ordered continuity, despite some conflictual currents, until two major events shattered that outward calm and rocked the consensus view of a general stability globally. These were Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years ago, and Hamas’ 7 October attack on border towns in southern Israel and a music festival that provoked a massive response by the Israeli military in Gaza and an ensuing humanitarian crisis.

Until those developments occurred, the Biden administration had foregrounded domestic policy — building up or rebuilding the national economy for the 21st century, especially new infrastructure and high-tech manufacturing to make the US more competitive with the country’s rival China (not yet termed an adversary).

While the administration did see Russia, yet again, as a potential adversary, that threat was seen as less crucial than the rivalry with China. Yes, the Middle East was, as always, a concern, but the focus was more on containing Iran’s ambitions as a regional powerhouse and bolstering a broad array of states — including Saudi Arabia, Israel, other Gulf states and Egypt — as an essential counterbalance.

In Africa, the core goals remained bolstering democratic societies, warding off the instabilities of civil wars (and Russian influence), improvements in public health, dealing with climate and meteorological disasters, and generating economic growth. There continued to be limited commitments of military forces to deal with the first two, and increased efforts for the rest via programmes such as Power Africa, Prosper Africa, the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), and the widely lauded anti-Aids programme Pepfar.

Specifically with South Africa, there was a solid base of more than 600 US companies operating in South Africa, South Africa’s trade surplus with the US, and the latter’s position as one of South Africa’s most important trading partners to build upon.

Additionally, there was a whole range of US NGO activities in South Africa and a large body of cultural, educational and international exchange connections between the two nations. Given this broad, diverse set of interactions, the relationship was deemed significant and solid, despite the fact South Africa seemed to be too mindful of Russian and Chinese temptations for the taste of US policymakers.

Is the relationship unravelling?

In the past two years, however, the official relationship has begun to sour on some key dimensions, given South Africa’s tilt towards Russia over its invasion of Ukraine (despite Pretoria’s protestations of neutrality). This has included effusive official visits by government and party leaders, joint military exercises and repeated public statements of those warm relations within the bilateral context and the BRICS formation.

Those actions have given US critics of South Africa — especially from among Republican members of Congress and some think tankers and commentators — ammunition to criticise South Africa’s actions and insist on holding up the relationship to much closer scrutiny than heretofore.

The warm support for the Rainbow Nation dating back to the 1990s has now faded away. Most recently, South African efforts to achieve the condemnation of Israel — in the wake of that nation’s invasion of Gaza — via a strong critique of it at the International Court of Justice and to charge it with genocidal acts has made official relations more problematic.

Then, in the wake of a Republican-led push to organise a full congressional review of the bilateral relationship, public statements by South Africa’s foreign minister that such an act was unacceptable probably fuelled the fire. Dirco Minister Naledi Pandor’s comments appeared to be a real misunderstanding (or poor advice by South Africa’s diplomats in Washington about the temper and tenor of feelings by Republicans and some Democrats) over the role Congress has in determining, evaluating, and criticising US foreign policy positions carried out by the executive.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Bill that calls for full review of US relations with SA crosses first hurdle in US Congress

Continuing her critique, Pandor wrote in a recent column in the Financial Times, “Since the advent of democracy in South Africa three decades ago, our mutually beneficial economic relations with the United States have surpassed expectations. Given the strong relationship between our countries, the recent introduction of a bilateral bill calling for the US to review its relations with South Africa is particularly disconcerting.

“The proposed bill, now in the House of Representatives, makes the claim that ‘the South African government has a history of siding with malign actors’ and will consider whether South Africa ‘has engaged in activities that undermine US national security or foreign policy interests’. These sentiments do not reflect the strong relationship that exists between us, or the intention of the South African government to strengthen that relationship.

“The bill also fails to acknowledge the right of all sovereign nations to develop and promote their own foreign policies. It criticises us for taking Israel to the International Court of Justice, where we argued that the actions of the Israeli military in Gaza violate international law and the Geneva Convention. In its ruling on provisional measures, the ICJ found ‘plausible’ evidence that Israel was conducting a genocide against the Palestinians in Gaza.”

Still, as things now stand, even a real frown of a review from Congress would be unlikely to lead to the abolition of US aid under Pepfar or access to grants and partnerships via programmes like Prosper Africa or Power Africa. But it might fuel efforts to remove South Africa from eligibility for tariff-free access to US markets under Agoa by graduating it out of the programme — assuming that law is renewed in 2025 when the current act expires.

Even if the end of Agoa access would not, by itself, wreak massive damage on the South African economy, it could easily be a serious blow to the agricultural and automotive export sectors. Further, it would signal a distinctly colder climate between the two nations as read by foreign investors.

At least at this point, the Biden administration has given little indication of an intention to make the bilateral relationship more fraught despite the Republican congressional critique, although more active efforts by South Africa on behalf of Russia in its Ukraine war, or yet more vociferous actions directed against Israel might strain things further.

Unpleasantnesses over the Lady R ship and accusations of a secret transfer of ammunition or weaponry to Russia have been put aside, and public statements continue to speak of encouraging greater investment, support for such investment and further encouragement of bilateral trade.

Negative rhetoric

A second Biden administration would be unlikely to alter the outlines of its course vis-à-vis South Africa in the absence of new, overt acts by the South African government (such as a post-election, left-left coalition government naming the US as a co-defendant with Israel at the ICJ in additional petitions). The same cannot be said of a putative second Trump administration, though.

There is already a well-documented track record of negative rhetoric towards Africa generally, and, occasionally, specifically towards South Africa over charges of a campaign against white farmers and their livelihoods. That comes in addition to feelings among Republican members of Congress that South Africa has received an easy pass on its international behaviour.

Moreover, in the Trump repertoire of policies, there is also a serious protectionist bias in its posture on international trade relations.

Given those leanings and the first Trump administration’s lack of concern for or interest in Africa generally, it is easy to imagine a second Trump administration finding ways to insist on concrete quid pro quos from African nations such as tariff-free access for all US exports in exchange for any US trade concessions, such as a new or renewed Agoa.

In such a climate, South Africa’s international posture could be in the crosshairs of a Trump administration, with Agoa eligibility on the line as well as the possibility some or all Pepfar funds might be transferred from South Africa to other less wealthy nations — or simply not appropriated at all.

Concurrently, it is possible to envision other policies that set out consequences for votes at the UN that run counter to what was perceived as US interests. Indeed, there would probably be little domestic political cost for such actions. Instead, they could generate short-term popularity among Trump’s supporters.

If this writer were asked for recommendations for South Africa, aside from avoiding sanctimonious lectures to US politicians about the great virtues of neutrality in foreign affairs and the fundamental cupidity of Israel, the most important acts might be to engage vigorously and strenuously with ongoing, major human rights and conflicts in Africa such as the horrors taking place in Sudan, northern Nigeria and elsewhere in the Sahel. There is also the mass suffering taking place in the eastern DRC as a result of the depredations of the M23 militia (although here, South Africa has, in fact, just announced plans to commit more military efforts).

Of course, taking a more sympathetic public stance towards the very real suffering and human rights violations occurring in Ukraine as a result of the Russian invasion would not hurt either. But none of that seems especially likely, given the current climate in South African policy circles, sadly. If so, a period of greater acrimony between a second Trump administration and South Africa next year may be inevitable.

In a future Trump administration, stances taken by other nations counter to whatever Trump believes at any given moment are likely to generate consequences — and probably deleterious ones. That would be the case unless, astonishingly, Trump somehow finds African authoritarians in the mould of Kim Jung-un or Vladimir Putin in power with whom he can exchange some “love letters”. Such an outcome would be very sad for democratic hopes in Africa. DM

Comments - Please login in order to comment.