THE CONVERSATION

Human geography study shows how to fix apartheid legacy in SA universities

A paper on outputs in human geography suggests that better-resourced universities could help poorer ones find funding and develop networks.

Knowledge matters. It informs how we think about the world around us. It informs our decisions and government policies, supporting economic growth and development.

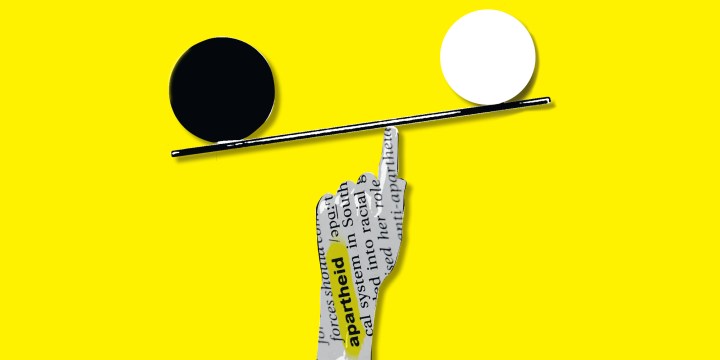

Knowledge is also power. Certain types of knowledge are given more value than others. This is driven by histories of privilege. In South Africa, apartheid looms large in debates about how knowledge is produced. Though it formally ended 30 years ago, it still influences whose knowledge is considered “right” and whose is sidelined.

And this matters in everyday lives. For instance, health and medical research and instruction used to focus on white and male bodies. This has directly affected the provision and quality of healthcare.

Crucially, control over the production of knowledge provides political, economic and social power. This has real effects on education, healthcare, social policy and service delivery.

In a recent research paper, we studied how apartheid legacies continue to affect the work of universities in South Africa. In particular, we looked at the outputs of the discipline of human geography, which is our specialisation. It’s the study of how space and time influence economic, social, political and cultural actions.

We found that universities that were historically more advantaged — that is, they served mostly white students — continue to outpace the country’s other institutions in terms of research output. This was true for the quantity and quality of publication outputs in journal articles and academic books and chapters.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Legacy of apartheid still haunts pupils fighting for a decent education in South Africa, 30 years later

Our findings show that apartheid’s legacy continues to affect academic output. This suggests that not enough has been done to address inequalities regarding funding, and networking, and opportunities for international collaboration. It means that South Africa’s academic landscape continues to reflect the views of a privileged few.

We examined what drove these disparities and identified strategies to begin shifting the dial.

Historical background

The history of South African human geography as a discipline is inextricably linked with colonialism. It was heavily influenced by conservative religious ideas and notions of racial superiority.

And during the apartheid era, topics were deliberately studied with a notional “non-political” focus, or research was used to support apartheid legislation.

In the 1970s, some research began to emerge about how apartheid policies affected black communities. This was a first. Research had largely toed the apartheid government’s line and not focused on the deleterious effects of segregation and oppression.

But, overall, universities either served white or “non-white” students. White universities were well resourced whereas others were not.

After 1994, South Africa’s human geographers turned to policy-relevant work as the country embarked on building a democracy. They began to support post-apartheid priorities related to the economy, small business and spatial development.

The same dominant hierarchies

The transition from apartheid led to the opening of South African universities. The racial makeup of institutions began to change. And South African academics began re-engaging with global academia after isolationist apartheid policies were lifted and international boycotts ended.

However, clear resourcing differences and hierarchies remain between (historically) advantaged and disadvantaged institutions. Consequently, the discipline remains dominated by a handful of departments.

Their dominance is maintained by income generation (student fees, publication income, grants), networks — and prestige.

Our research shows that academics from historically disadvantaged institutions feel removed from these global and national networks.

We found a significant concentration of research outputs among a few (historically) advantaged institutions. This allows them to generate research income and mobilise international collaborations to fund larger projects.

This also allows academics to take on lighter teaching loads, and gives them more time to conduct and publish research.

International collaborators are drawn by these institutions’ reputations, histories and resources. It’s easier for academics to visit international universities and participate in international funding applications.

Such institutions are also able to support young human geography academics and encourage greater publication outputs in ways that underresourced and small departments struggle to match.

Human geographers at historically advantaged universities have mobilised international networks to appoint overseas academics to honorary positions. These moves boost the institutions’ publication outputs — and their income from government subsidies and incentives.

As one interviewee described it, the cycle of opportunity and prestige for historically advantaged institutions leaves historically black institutions always on the back foot — the playing ground is not levelled.

The way forward

These challenges could be addressed in several ways. One approach might be for more resourced universities to support historically disadvantaged institutions in developing contacts, networks and strategic policies to attract and appoint visiting research fellows.

This would open up opportunities for funding, which, ultimately, will lead to more research and knowledge being produced.

Many of our interviewees said that more collaboration was needed between historically advantaged and disadvantaged institutions. This should be encouraged.

Human geographers from historically disadvantaged universities must be consulted about what kinds of support they need, rather than ideas being imposed by those from well-resourced institutions.

Other priorities could include stronger mentoring for early- and mid-career staff. Training is crucial, too, to develop skills in journal and grant writing.

Even something as simple as institutions updating online staff profiles would be valuable. This helps to promote individuals’ research interests. It also supports network-building and collaborations.

Perhaps, most of all, there’s a need — as one interviewee told us — to push for difficult conversations about inequalities and shortcomings to “shed light on what is missing”.

Ultimately, commitment is required to realise a more ethical South African human geography. The government, universities and individual academics all have a role to play in fostering inclusion and collaboration that work beyond historical inequalities.

This will help to make the subdiscipline more robust and cutting-edge. And that’s ultimately beneficial to academics, students and the country at large. DM

First published by The Conversation.

Gijsbert Hoogendoorn is a professor in tourism geography at the University of Johannesburg; Daniel Hammett is a lecturer in development and political geography at the University of Sheffield in England; Mukovhe Masutha is a senior research fellow at the University of Johannesburg.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Garbage

Yes, rubbish. Take this jewel from the article: “For instance, health and medical research and instruction used to focus on white and male bodies.”

Want to bet these same researches are going to tell you race doesn’t exist and is just a social construct? So if the latter is true, what does it matter on which race you do medical research?

Shem, still holding on to the past for dear life – it’s been over 30 years now, lack of change is on the current lot, not those that left 30 years ago

Why are the previously non-white universities not advanced in terms of their capability, i was at WITS in 1983 doing engineering and half the course then were non white students? How is it we have not improved the quality and capability of these so called under-resourced Universities. Wits used to be one of the best Engineering Universities in the world, this is no longer the case, i blame the minister of higher education and the incumbent government for these failings.

Its because the articla talks s. The reality is nothing has moved forward because we have a Carter running the country. This blaming the whites for everything is getting old now. The so called white universities do well because all the rich whites give money to them. If rich blacks game money to wits it would be just as great. If they use it like they should and dont go to dubai for hdays with that money

Knowledge and the pursuit of knowledge, is universal and serves to benefit all societies the World over. Institutions that develop as the repositories of knowledge, and pursue such knowledge and the deepening of such knowledge, benefit us all. IQ is the key quotient.

And this is the key differentiator as to how societies grow, develop, nurture and deepen knowledge, to the ultimate benefit of us all.

That IQ is not uniformly spread around the World – much of Asia has a median IQ of around 105, Europe, and European societies around 100, and Africa around 70, are key determinants and limitors, of the development and advancement of societies and knowledge.

Equally it is true that different societies place different weights to the pursuit of knowledge. Pondering on these factors will be more helpful in analysing the differences in development the authors of this article are seeking to shed light upon.

For the last couple of years already most NRF Grants require that previously advantaged HEIs partner in all projects with historically disadvantaged HEIs. Seems there are no positive publication spin offs from this then if HDIs still lag.

What should also be considered is that the HDIs also employs a lot of foreign (rest of Africa) academics which are very well-trained and publish regularly.

I have a PhD in Chemistry and was fortunate to publish several papers and to act as copromotor for several MSc students at Stellenbosch in the late 90’s. Even then previously disadvantaged universities were getting a lot of money thrown at them and a lot more access to international grants etc. Nowadays most grants are for black academics and/or for work that involves mostly black students. Most of the students I mentored for PhD couldn’t find afterwards in South Africa but today they are directors of international companies. Even in the 90’s before rampant BEE I could not employ white male students while I worked for Plascon. This so-called academic work is the worst I’ve seen to date. It follows close on the suspicion that these gentlemen only got funding if they agreed to write about Apartheid’s legacy. I tell you now that when you talk to black educators they are more interested in the next conference they will attend. They live the high life instead of focusing on their students. They don’t deserve any help. It appears DM focuses a lot on this kind of carbage instead of finding the truth. The truth is those universities that excel 30 years on in this so-called democracy do so through merit.

So where are the facts? This is all speculation and opinions?