BOOK EXCERPT

History and the hybrid beast — horses and the indigenous resistance in the Cape

In this excerpt from Sandra Swart’s The Lion’s Historian, the history professor looks at the Cape’s past through an equine lens, showing how becoming mounted created dominance – and not only for the colonialists.

In 1952 a Juǀʼhoansi man named Kxao was asked by an anthropologist if he had an image of God in his mind. Kxao lived in arid Nyae Nyae, subsisting, as had his forebears, by nomadic hunting and gathering, oppressed by the state, and living with no livestock and no permanent towns. His people had no great faith in the beneficence of authorities or gods; even the supreme creator was both a life-giver and death-giver, and supernatural beings brought discord and disaster. Kxao thought about the question and then declared: “God is a man on a horse with a gun.” … This strange symbiosis between ungulate and primate began at least six millennia ago on the Asian steppelands but came together in southern Africa in the mid-17th century to create a third much more powerful animal: the horseman. This hybrid beast was a neurobiological and physical wonder. This new creature had the power to make history.

History has held a certain vision of our equestrian past. In this version, horse and man appear as a dyad integral to great narratives of times gone by – of the rise of kingdoms and states, of technology and industrialisation, of class formation, of the making and unmaking of nations and empires, of the emergence of politics and war.

***

The orthodox narrative is of conquest: dominance over the horse followed by the immediate and obvious use of this “horse power” for dominating other humans. This created a technology of power, epitomised by the horsemen of the apocalypse: horses and war, horses and conquest. Conventional stories of conquest begin with the human side of the dyad, but ours begins with the horses because it is really their capabilities that made it all possible. Horses were able to be the partner humans needed because their somatosensory cortex could interpret the signals of the sensitive receptor cells in their skin and convert pressures exerted by the rider’s shifting bodily movements to neural impulses that the horse’s brain could understand.

Ngorongoro man-eater signs. People outside lions’ home ranges forget how dangerous they can be – yet co-existence is possible. (Photo: Hadas Kushnir)

In these interspecies pairs – prey and predator, herbivore and omnivore – communication is effected through the intimate, tactile language of shared contact through riding. It is a fragile language, easily misunderstood by the uninitiated of either species. Pressure signals from each animal are sensed and diffused through peripheral nerves leading through each of the two species’ spinal cords. These signals are construed in each animal’s brain and a learned reaction is then sent back through the spinal cord and nerves. These interspecies neurobiological conversations formed the bedrock of the new horsemanship in southern Africa that was sweeping up from the Cape. Essentially, each species was suddenly liberated from [its] own original species and transformed by the body and mind of the other… Speed, cognition, vigilance and power multiplied. Humans were suddenly elevated above ground level, able to see far and wide, while looking down on other humans. A mounted soldier had the advantage over ordinary foot soldiers owing to the increased height and speed. People could suddenly move at a miraculous 30km per hour. Time and distance contracted. Possibilities opened. The world became smaller and human command greater. As the quarry of formidable carnivores, horses had evolved a prey mentality and a fast body to escape predators. How ironic that humans and horses together became the ultimate predator – conquering humans on foot, hunting other ungulates, and allowing the symbiotic spread of horses and humans around the world – a stride forward for mounting globalisation.

For those seeing horsemen for the first time, the spectacle must have been terrifying… In the conquest of the Americas, indigenous groups confronted by the horsemen led by Hernando Cortés were said to believe horse and rider were one and the same – composing a supra-human Spanish conquistador. Yet in the past, “the involvement of native peoples with horses has been written out, ignored in tales of colonial conquest. Horses unwittingly became part of the way indigenous peoples were subjugated – and those people’s own knowledges of horses too often were denied…” The equines of empire were marooned in a hostile landscape of disease, scant forage, poisonous plants and dangerous predators – both animal and human. Yet even as they helped their human fellows create a more-than-human conqueror, they also created a supra-human resistance to these invaders.

The lion sleeps tonight – with a little help from us. (Photo: Sandra Swart)

Quaggas were plentiful in the Cape in the 1600s when horses arrived. (Photo: March Turnbull)

“Horsepower” might be an imperial unit of power, but this had a more literal history in southern Africa. One of the first European settlers in southern Africa was a horse. This creature was the sole survivor of a mid-17th-century shipwreck on the Cape of Storms. Wearing the rotting remnants of a rope halter, this horse was sometimes glimpsed by the sailors who arrived with the first wave of white settlement, but he had become so wild he could not be caught. He was utterly alone. Although species of the genus Equus – like the zebra and ass – have been present in Africa since earlier times, the horse (Equus caballus) is not indigenous to the continent…

Horses were the first domestic stock imported by the settlers. The early colonial state that emerged – despite resistance from both indigenous groups and the metropole – was based at least in part on the power of the horse in the realm of agriculture, the military and communications…

From 1659, a year that saw Khoe forays against outlying settler farms, the Dutch East India Company permitted more horses to be imported from the East, with Jan van Riebeeck insisting that the very preservation of his nascent settlement depended on them. After their hard-fought introduction, horses were first used as draught animals to effect changes in the new environment but they were also deployed on a more symbolic level – as a signifier of settler power. These horses were intended to inspire fear in the Khoekhoe, who were beginning to raid the settlement, by drawing on an entrenched tradition in which horses had long been associated in western Europe with the society of the elite and with the culture of hegemony. The horse distinguished the ruler from the ruled, with the rider a symbol of dominance. Van Riebeeck was darkly gratified when the local clans seemed suitably awed by his horses. This was to lay the foundation of the use of horses in southern Africa as integral to symbolic displays of power, which persists all the way up to the modern day.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Mamre – a village in love with horses

These spectacles went hand in hand with the violent deployment of horses in the pursuit and maintenance of control. The first settler commando was set up in 1670. It was a new institution for frontier policing actions (rather than defence against coastal attack from foreign powers). It was essentially a unit of “mounted infantry”, travelling as cavalry and attacking on foot: the men dismounted to shoot, fired, retreated, reloaded and then charged again. The commando developed as part of the social machinery in the construction of masculine settler identity. Horses facilitated the psycho-social subjugation of the indigenous population (and later, to a limited extent, highlighted the differences between various white groups).

One of the key visible hallmarks of authority at the Cape was riding. Indeed, a fundamental indicator of male vrijburger (free burgher) identity was the right to own a horse and gun. In an early 19th-century rebellion by enslaved people, the rebel leaders dared to commandeer horses. In an almost saturnalian “turning the world upside down”, they performed their shift from slaves to free rebel leaders by climbing off their wagons and mounting the horses. It was highly symbolic when the rebels ordered white farmers to dismount. Even more tellingly, after the rebellion was crushed, in their ensuing defence plea, one rebel was more willing to admit to his possession of a gun than a horse, while a number of insurgents contended that they had “been put” onto horses in order to lessen “their active guilt in such a symbolic transgression”. In other words, they were protesting their innocence of having literally got on their “high horses” – which was no place for them in that social order.

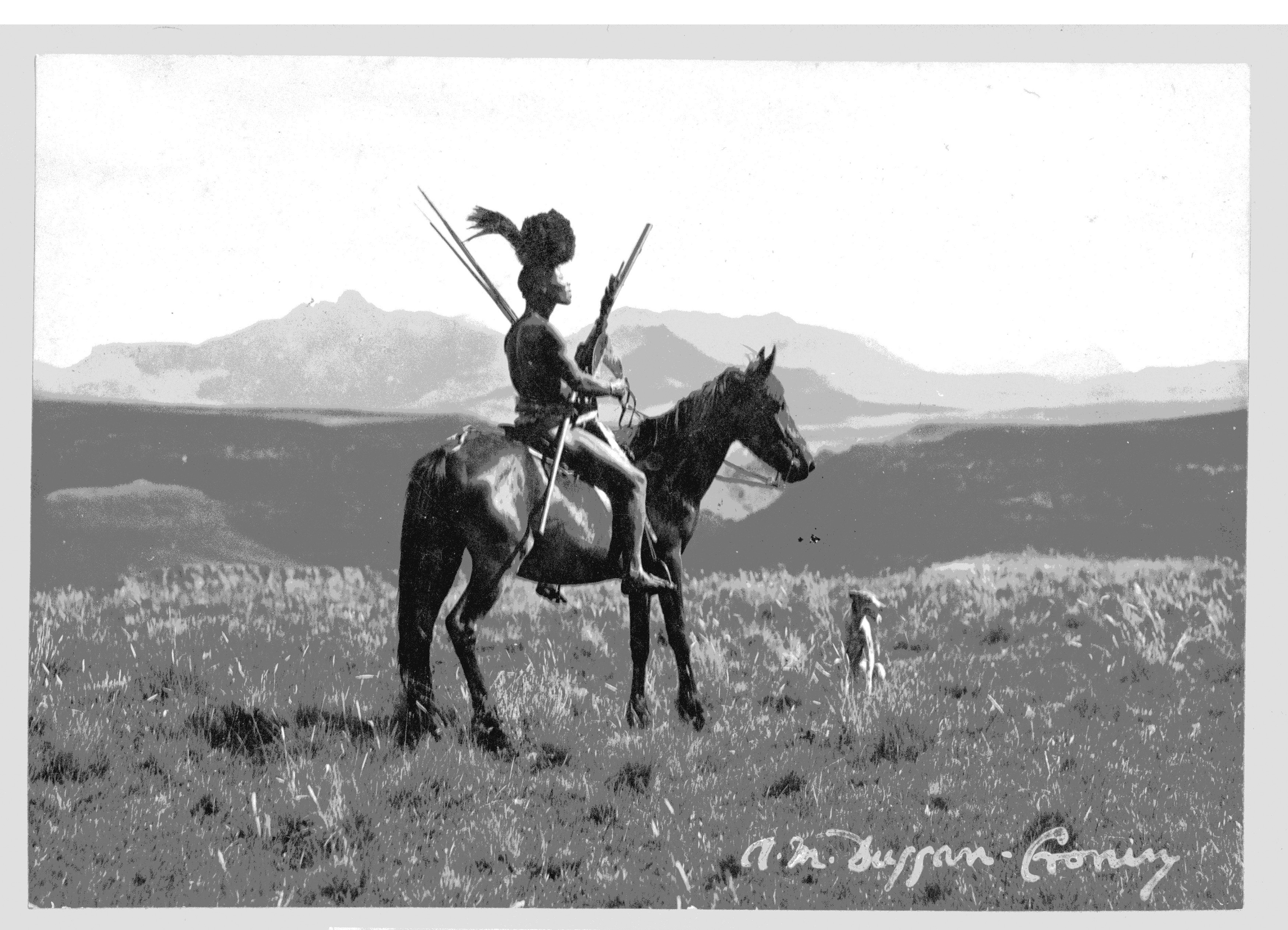

Taming horses gave riders incredible speed and height. The advantages were used to dominate and subjugate.

Animals, including dogs, lions and jackals, have shaped Africa’s history. Here a German shepherd is trained on the mines. (Photo: McGregor Museum, Kimberley)

Human hunters long ago learnt the language of jackals. (Photo: André Greyling)

At the Cape, pale horsemen seemed apocalyptic. Horses spread with settlers in waves of conquest, giving them a military advantage. As we have seen echoed in Kxao’s laconic lament, the San suffered genocidal oppression from these mounted commandos…

The white authorities initially tried to monopolise both trade and ownership, but neither attempt proved successful. As the migrations of different groups escalated in the early 19th century, white settlers were strictly forbidden to trade guns or horses with neighbouring African people. Although Boers grumbled about English traders handing over such bounty, they themselves also did not “refrain from making a bargain now and then themselves”. Throughout the 19th century, travellers noted increasing encounters with horse-owning indigenous groups, and vexed white military officials recorded the accumulation of horses by potential African adversaries. San rock art began to depict both black and white horsemen.

Once they were better understood, horses became coveted. Local groups frequently converted desire into possession. Just as with guns, the Khoekhoe were at first cautious but quickly embraced the new technology in so far as they could gain access to it. At first, this was done illegally. In the 18th century, when the Cape claimed jurisdiction over all Khoekhoe, they were explicitly forbidden to possess horses. Some San incorporated the horses they themselves captured into their hunting practices, often riding them bareback, for example, to help run down eland. The myth of a massive divide between those of pastoralist inclination and hunter-gatherers has long been exploded. San leapt this gulf easily, acquiring (although not breeding) horses and becoming adroit riders – where their environment permitted horse-keeping…

Read more in Daily Maverick: ‘Ghosts of the Past’: A galloping tale of horses, hidden gold, genocide and skullduggery

The last generations of Maloti-Drakensberg hunter-gatherers certainly raided, rode and consumed horses. In the mountains’ rugged east-facing escarpment, the AmaTola, a creolised group of mounted raiders composed of Bushmen, Khoe, Nguni people and a miscellany of recruits from other groups, assimilated horses not only into their new raiding existence, but into a belief system already replete with creatures. The AmaTola initially brought horses to the Drakensberg from the eastern Cape frontier and raided cattle from Bantu-speakers and white farmers below the escarpment. They proceeded to forge a fresh identity using a new combination of symbols and leaving a residue of their religious thought in rock paintings. This is a recurring pattern in the paintings of horses and their riders in connection with baboons, horses and therianthropes. Baboons and horses were key to the religious ideology of these riders. During ritual dances, such power could be harnessed: the dancing humans were depicted changing into baboons and horses. Thus shamans literally became “horsemen” – like the centaurs of Greek myth – shifting between human, horse and baboon and assuming their protective powers to keep the AmaTola safe on their mounted forays. Thus the tools of colonialism and conquest were appropriated not only materially by the mounted raiders but also symbolically in their new cosmology. Kxao would have understood. DM

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Fascinating!

Fascinating topic, if rather dryly written

Having only read this now … it gives me goosebumps to see the similarity to other conflicts … like the current one in the middle east ! There it seems that a group of ‘colonists’ with their access to AI and ‘technology’ can forever subjugate and humiliate another people, and allege ‘proxy’ involvement, if that ‘power’ is challenged. The absolute hubris has to be seen to be believed. Even journalists trying to ‘document’ that arrogance, have now been added to the list of proxies to be ‘eliminated’ ! Thanks for the historical insight into a particular mindset.