HORSE RACING (PART 4)

Mamre – a village in love with horses

Research for this series began with an assumption that horse racing constituted animal cruelty. Worst was ‘bush’ racing: often bareback on rough veld or rocky roads with unshod horses in poor condition raced for money. I heard it was going on in Mamre – a village up the Cape West Coast – and went to investigate. What I found was something else entirely: a village in love with horses.

‘I had this horse called Amy,” says Oscar Pick. “When the veld was dry she’d come home for water. Walk through the front door and out the back door into the yard. I cried when she died.”

Oscar’s a big man with a wide smile and an equally large influence in the West Coast Moravian village of Mamre. When you talk about horses he gets misty-eyed. He has more than 100; owning horses is a family tradition that goes back many generations.

“The only thing a horse can’t do is talk. If it doesn’t like you, there’s something wrong with you. If I see a kid being cruel to a horse I’ll moer him.”

I’m in Mamre to witness a road race at Rooipad, a sloping, sandy public road just outside the village. There’s a mix-up – it’s the following weekend – but it gives me time to poke around.

Mamre was established by German Moravian missionaries in 1808. It became a haven for slaves freed in the 1830s and later took in Khoisan inboekselings who were being grabbed by Dutch farmers to replace their lost slaves.

At its heart is a church, watermill, community hall, some buildings that must once have been residences and the pastor’s house. They’re all very old, rather battered with thatch in need of repair, but charming. The graveyard on the hill has many German names.

Right now it’s spring and brightly coloured flowers are everywhere, a patch being cropped by three horses beside the mill. A wedding is in progress and I pause to snap the bridal couple being photographed. It’s hard to visualise a more perfect setting for a nuptial.

In the village there are corrugated iron backyard paddocks everywhere with horses leaning over rickety fences. Before leaving, I stop to buy some water and a bite to eat. Three young men arrive on horseback, hitch their reins round the shop gate and amble in. Cowboy comparisons are irresistible. On the way out I pass a teenage couple on a large brown stallion riding bareback with the ease of rodeo performers.

A week later

The following Saturday I’m back for the race. There are horses everywhere, mostly bearing young men prancing before admiring girls. There’s a buzz of excitement.

I’d expected to see bony nags with fence-wire bridles, but these are mostly magnificent beasts with good tack. None have saddles or stirrups, but their adept riders sit tight and don’t seem to need them.

I seek out race organiser Darian Adams. “I first fell off a horse when I was three,” he laughs as we sit on his stoep with a ball-obsessed golden Labrador. “My father and uncles had them, but they all died of horse sickness around 2014.

“Then I helped an old guy change a tyre on the road and he said I could have his horses as he no longer wanted them. Big payment for a good deed, hey? That was my first five. Now I breed them.”

I ask him about the upcoming race, but he says we need to talk about its context because racing is a small part of what horses mean to Mamre.

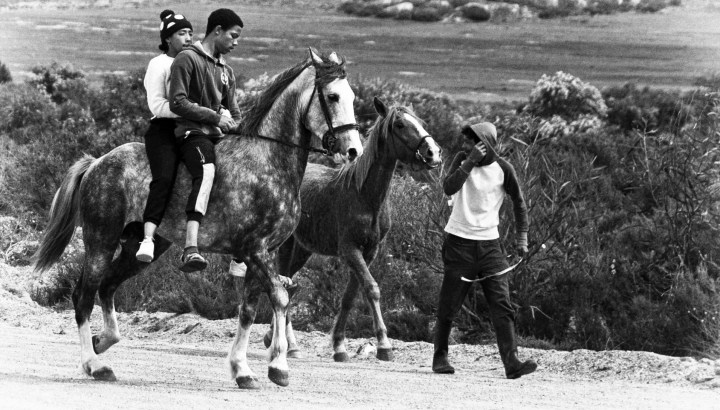

Before there were cars in Mamre, there were horses – and they’re still there doing the job. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

“Everyone in Mamre lives for horses,” he says, “that’s what makes it different to other places. I’ll do anything for a horse. I have vets on speed-call and they tell me what to do if someone has a problem with a horse. I source medical supplies.”

There are about 1,000 horses on community land surrounding the village, he says – some owned, many wild – and maybe 500 in the village. The last census put the human population at 9,048, which means an astonishing ratio of a horse to every six people or 1.4 horses per household.

“Under a voluntary group called Mamre Equestrian Club, they have gymkhana, commandos, Horse Wash Day, where they get the young guys together to wash all the horses for free. They do clinics where vets come speak to the guys about horse care and they bring in farriers to trim the hooves.”

The commando, he says, was learnt from the Boers. It’s a 25km gentle outride with a boerie braai halfway. “They take a tractor with a wagon for all the food and family and friends who want to come along. They put up a camp, there’s a DJ, campfire. They sleep over and ride back the next morning.”

The gymkhana is evidently a great crowd-pleaser, where horses and owners have to work together on tasks that must be a puzzle for the horses.

“They have an egg-and-spoon race … There’s an obstacle course you have to ride between poles. They have the ‘lemon tree’ where there are lemons on strings hanging from a pole and you have to … bring them back. There’s musical chairs with horses using sticks instead of chairs. There’s a balloon challenge … They have big crowds.”

Darian and I have moved to a park with kids riding a roundabout and some dads passing round a zol. Time to talk about racing, which happens three or four times a year.

“There’s no gambling,” he tells me. “The winner gets a trophy and there’ll be a bag of food, some tack, saddles or bridles as prizes. Most of the horse owners are youngsters.

“We race for the fun, for bragging rights. In Mamre you get seen when you have a horse. You get popular. It’s not about cellphones or fast cars or cool clothes, it’s about horses. With a horse you’re cool. When you have a nice-looking horse, girls all check you out.”

“The challenger this year is Emile Meyer and his horse Siraj. That horse keeps improving. There are a few guys with Arabians and Emile wants to challenge them. He has a lot of fans. I hope there’s no skelem where somebody blocks another horse.

We watch the kids speeding up the roundabout as a toddler hangs on for dear life. I’m waiting for an accident to happen, but it doesn’t. Maybe soon they’ll all be riding horses.

“Young people with horses don’t cause shit,” says Darian. “You have to be responsible if you own a horse. In summer they ride to the beach to take their horse for a swim and make a braai.” He glances at his watch. “Time to go.”

The Mamre race track is a section of a public road called Rooipad. It’s sandy, stony and a tough ride for unshod horses. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

The race

The road to Rooipad is extruding horses, smart bakkies, old tjorries, kids on bicycles, scooters and even skateboards plus people on foot, all heading for the T-junction where a farm road hits the R307. Vehicles are backing up at the finish line while horses and riders wait along a fence beside the track.

The start is up a hill and just out of sight – maybe 2km away – and the race ends at the T-junction. The surface is gravelly and sandy. There’s no finish line to cross and a photo finish would definitely cause a good deal of argument.

Unlike other gatherings in the Western Cape, there’s little evidence of hard drinking and only the occasional whiff of dagga. The riders’ preferred drink seems to be Coke.

There are some fine horses, including a unicorn-like speckled Appaloosa, a pinto in brown and white cryptic camo, a powerful Arab and a shiny, coal-black stallion given to rearing. How its stirrup-less, saddle-less rider says on its back is hard to figure.

The official starting time comes and goes but horses and riders are still streaming in. There are maybe 30 along the fence and their riders are joshing each other and scratching their horses behind their ears, which they seem to like.

Finally, five come onto the road and set off up the hill with seemingly no instruction from Darian. The start appears to entail someone shouting “go” and they all come thundering towards us, legs and arms all over the place. What keeps their backsides on the horse is impossible to figure out. There’s a good deal of cheering and the horses go back to the fence.

After several such casual races things seem to be getting more serious, with Darian riding behind the pack in his bakkie becoming covered in dust from flying hooves.

One race is won by a horse whose rider is a girl looking no older than 15. In another, a horse stumbles at full gallop and goes down, with horse and rider upside down in the dust, legs flailing.

Occasionally falls happen. Here neither were injured and the horse continued the race. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

The horse gets up and continues the race, its rider, amped on adrenalin, runs to the fence and back again to the road, yelling, then finally calms down while being checked for damage, none being visible.

There’s no prior hype about the championship race. Seven horses head up the hill and, after a pause during which we can’t see them, they come thundering back over the brow of the hill. The winner gets a hearty cheer but it’s not Emile Meyer and Siraj, it’s William Marnus on Stout. Maybe next time, Emile.

The crowd begins drifting away, interspersed with horses and riders, some with girlfriends riding pillion, all heading back into Mamre.

Darian pulls up. “Last race of the year is next month. Come,” he says. “But also come to the gymkhana. You’ll love it.”

After fussing over my notes and camera for a bit, I look up and find the T-junction deserted. The only evidence that anything happened there are a few piles of horse shit and an empty Coke can. Back in the village riderless horses are wandering around, cropping flowers.

They ride bareback, fast and even barefoot. It is unconventional horse racing but they’re excellent riders. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

After months of exploring horse racing in South Africa, I’m left with this conclusion. It’s unlikely any horse enjoys galloping around with a primate on its back. But if its existence depends on that, it would probably prefer to be a free-roaming Mamre bosperd up for an occasional race than a pampered Thoroughbred in a stable forced to run its heart out every week to keep touts and bookies in Range Rovers and Maseratis. DM/OBP

You can read Horse Racing Part 1 here, Part 2 here and Part 3 here.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R25.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.