REFLECTION

Vernie February – A lifetime spent playing an away match

The South African academic and poet Vernie February was highly respected in the Netherlands, his home from home for 38 years. His doctoral thesis – a seminal work on the ‘Coloured’ stereotype in South African literature – was published in 1980 as ‘Mind Your Colour’. Being in exile for 27 years meant he was not as well known in South Africa as he deserved to be, although after 1990 he spent extended periods as a guest professor at the University of the Western Cape where students benefited from his encyclopaedic knowledge of South African, African and Caribbean literature and languages, as well as his passion for imparting it. Anthony Akerman reflects on their friendship on the 21st anniversary of his death.

‘In exile, you’re always playing an away match.”

It sounded catchy and aphoristic, but I didn’t really know what he meant. An away match was an alien concept as I had no interest in sport. But it wasn’t long before I understood exactly what Vernie February was talking about.

When I met him in Amsterdam, I’d been away from home for three years. Did that make me an exile? There are two types of exiles: those who can’t return home, and voluntary exiles. I fell into the second category, but I’d started burning bridges.

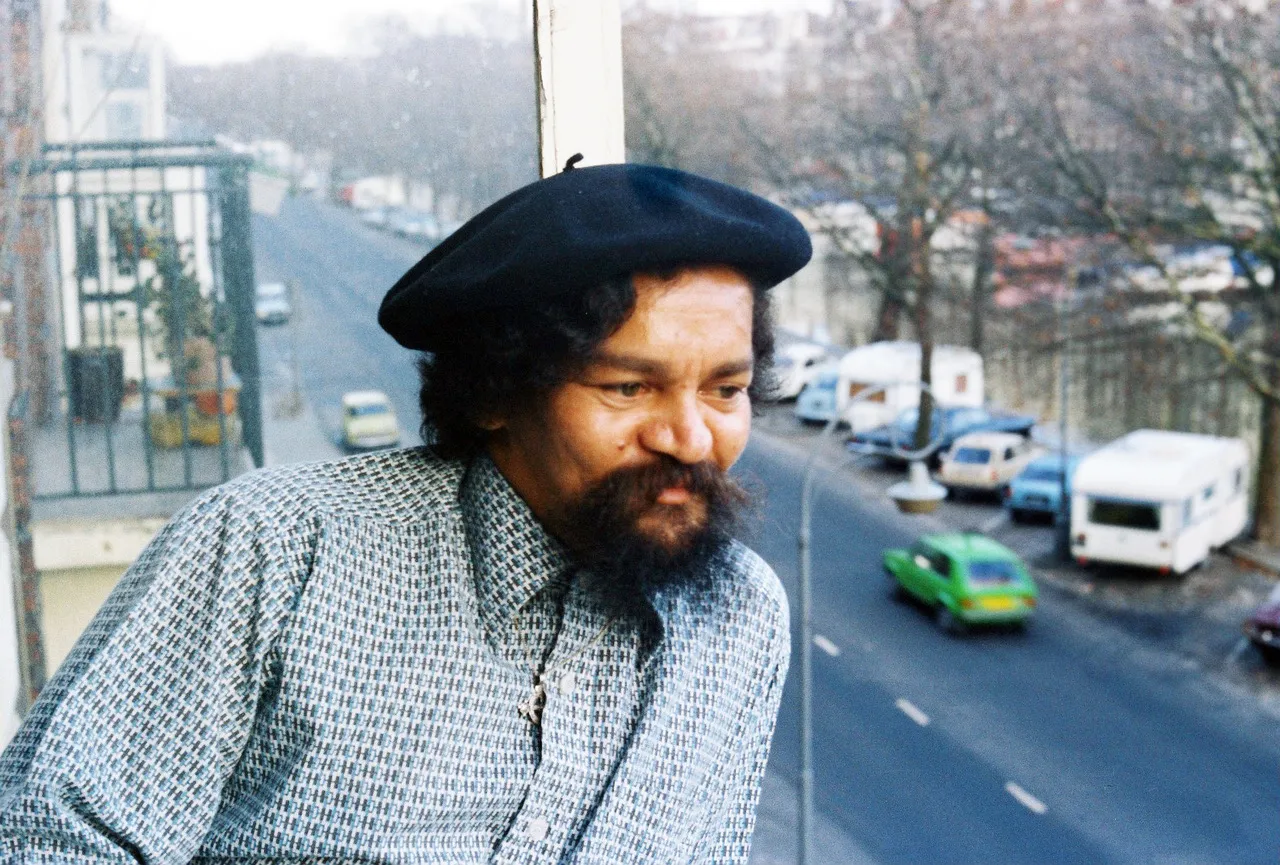

Vernie February between marriages on the Nassaukade, circa 1976. (Photo: Anthony Akerman)

Vernie was between marriages, so we spent many late nights in meandering conversation that became progressively bibulous – something that was not good for his health, he told me, because he had a dicky heart.

His marriage to a Scandinavian woman had ended in tears. I knew all about that – about relationships ending in tears, that is, not Scandinavian beauties like Britt Ekland who was, when I grew up, the unattainable fantasy of most adolescent boys. He rarely saw his daughter Rushika as his ex-wife had custody; relations were strained and they lived abroad.

People looked up from their drinks when Vernie walked into one of Amsterdam’s smoky brown cafés sporting an unruly Van Dyck beard and his signature black beret. He was warm, gregarious and had an infectious laugh. When we met, he’d already been in exile for 12 years.

That’s a lot of away matches.

***

He’d majored in English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa at UCT before apartheid legislation had completely segregated universities.

Opportunities for someone with Vernie’s talent were shrinking fast, and the repressive clampdown following the Sharpeville Massacre meant political dissent inevitably resulted in imprisonment.

He left the country in 1963 on a scholarship to study in the Netherlands; his cousin also left the country, but he joined uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK). In 1967, en route through what was then Rhodesia to infiltrate South Africa with his guerrilla unit, Basil February became the first “Coloured” casualty of the armed struggle.

Vernie was born and grew up in Somerset West. His father died when he was six and his mother supported him and his five brothers. He owed so much to her, he said, and her death the year before was still raw.

“Could you go to her funeral?”

“They allowed me in for five days,” he said.

When he became a Dutch citizen, he had to renounce his South African citizenship, which is why he needed a visa. He told me how, the day after he arrived, there was a knock on the kitchen door of the family home. It was a courtesy call from the Special Branch – just to let him know they were keeping an eye on him.

He hadn’t seen his mother in 11 years when they buried her in the Somerset West Cemetery with his father, his grandparents and many uncles and aunts.

I thought it was brave of him to go home, but he felt confident his Dutch passport gave him a measure of protection. I still had a South African passport and the army wanted me for camps. If Mum or Dad died, I knew I wouldn’t be at the funeral. So I was an exile, after all.

We spoke about homesickness. Vernie shook his head ruefully, took a sip of his drink and locked eyes with me: “You can take a man out of the country,” he said, “but you can never take the country out of a man.”

He may have been naturalised Dutch, but the country of his soul was South Africa. Several years later, when I sat down to write a play about South African exiles in Amsterdam, I called it A Man Out of the Country.

Vernie was on the academic staff of the African Studies Centre in Leiden and, in 1977, was awarded his PhD. He told me with a mischievous glint in his eye that his supervisor didn’t understand his title. What was the title?

“Flagellated Skin, a Fine Fetish,” he said.

I assumed an expression I hoped looked more intelligent than his supervisor’s. Sometimes being in the theatre gives you an edge. The topic, he explained, was the “Coloured” stereotype in South African literature.

To borrow one of Vernie’s favourite expressions, he’d already forgotten more about South African literature than I’d ever known.

I’d only read The Story of an African Farm, Cry, the Beloved Country, Herman Charles Bosman’s Mafeking Road and, of course, Athol Fugard’s plays. Who better to ask than Vernie? He told me a good start would be to read Laurens van der Post’s Introduction to Turbott Wolfe. Turbott Wolfe?

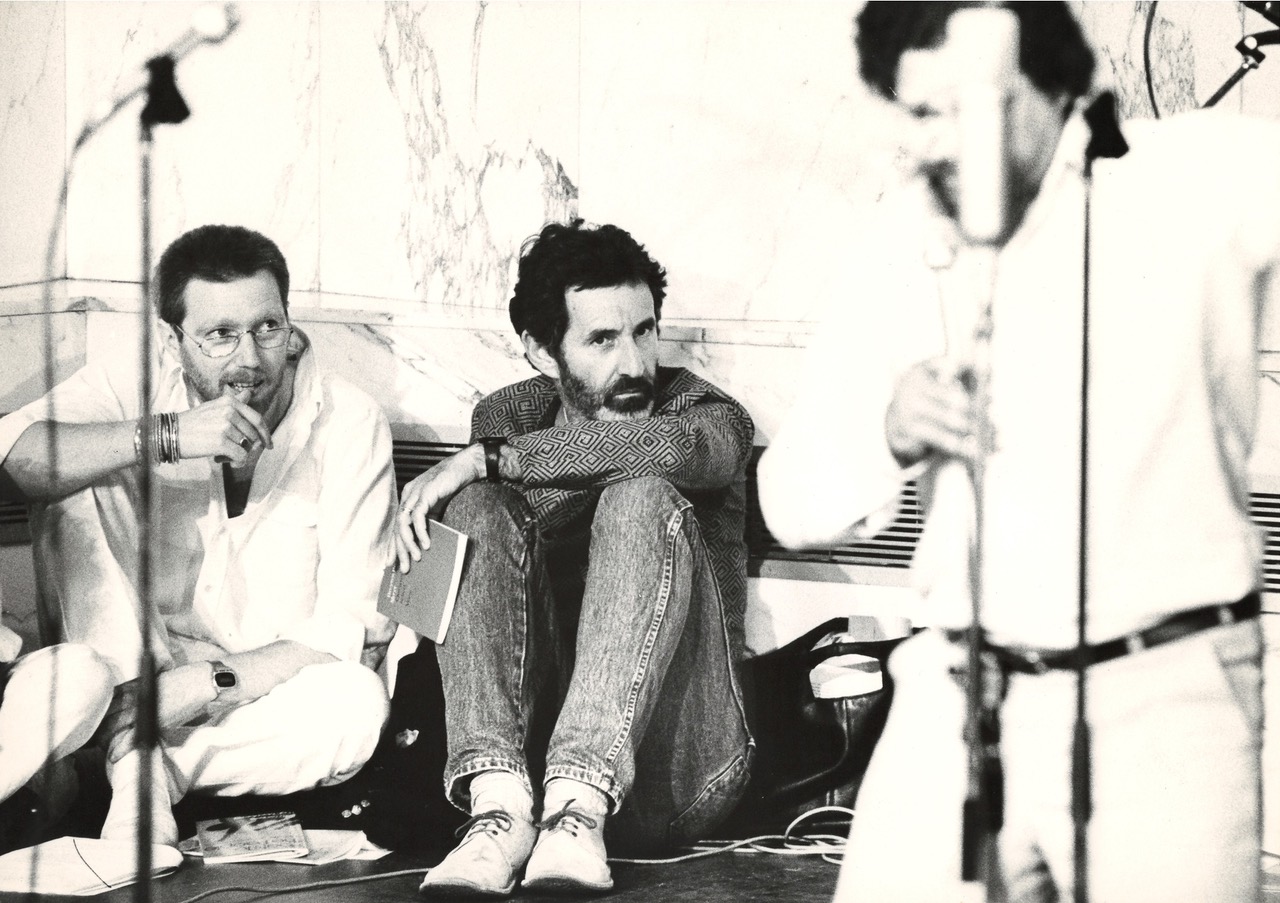

Anthony Akerman and Breyten Breytenbach watch as Vernie February reads a poem at Poetry International Rotterdam in 1983. (Photo: Leo van Velzen)

“William Plomer’s novel. Its portrayal of miscegenation scandalised colonial society when it was published in 1925. The Natal Advertiser said the novel was not cricket!”

Thankfully he didn’t make me write essays on all the books he recommended – in both English and Afrikaans – but I was grateful to have a mentor and friend all in one.

When Kegan Paul agreed to publish his manuscript based on “Flagellated Skin, a Fine Fetish”, it justified a celebratory visit to Café Hoppe. Over a Grolsch or three, Vernie said the publisher had hinted the title might make the book a hard sell.

I added, somewhat flippantly, that there was also the possibility that customers browsing the shelves in a bookshop might think a book with that title was about a sadomasochistic mediaeval monk. That remark probably went down like a fart at a wedding, but we’d had a few drinks.

As I’d already banked a title Vernie had given me, I felt I should make a constructive suggestion and tentatively offered it as a quid pro quo.

I recalled a story told to me by my friend Doug Hindson, who was then Professor of Sociology at Wits University. When he was doing his Master’s at Rhodes University, Doug had been in the whites-only, men’s bar at the Cathcart Arms watching three guys playing a competitive game of darts.

They’d also been drinking competitively and when one of the three – the one who had a slightly darker skin tone – became rowdy, one of the others turned to him, lowered his voice and said, “Hey, mind your colour!” Vernie shook his head sadly. Then, a moment later, the penny dropped. His eyes lit up, and he squeezed my arm and smiled broadly.

I’d hate to give the impression Vernie and I were heavy drinkers, but one night we were having a deep and meaningful discussion in Café de Prins. My beard had a reddish tinge in those days and I was leaning on my elbow with my hand covering my left ear as Vernie preened his Van Dyck beard and made a categorical ruling that bobotie simply wasn’t the same without Mrs Ball’s chutney.

Just then an inebriated local stumbled past our table and did a double take. He made a slow and unsteady about-turn, gaped at us goggle-eyed and slurred thickly, ‘Mijn God, Rembrandt van Rijn en Vincent van Gogh!’

***

After Vernie married Esther, she provided a loving, kosher home for him and – in both senses of the word – took great care of his heart. When I visited, she’d politely ask me to go outside to smoke for the sake of his health. At the time, it seemed an outrageous request but I reluctantly acquiesced.

After Naomi was born, Vernie was very much a family man and long nights in brown cafés grappling with weighty philosophical subjects became a distant memory.

In March 1984, Alfred Tshabangu – a.k.a. Pinkie – killed himself. He’d had a long and chequered history in the struggle. He was married to a Dutch woman with whom he had a daughter.

He was engaging and entertaining, but exile and chronic homesickness had driven him to drink – and, arguably, suicide. This happened when I was working on A Man Out of the Country and his death both saddened and disturbed me as he was the model for a character in the play.

Vernie knew Pinkie well and told me he and Basil had trained together in MK. The burial was at Zorgvlied. I drove to the cemetery with Joseph Mosikili, a friend and actor, who’d been close to Pinkie. It was a cold April day and the weather changed from sun to rain to wet snow.

As we stood around the grave, the master of ceremonies expressed the hope that by the year 2000, Pinkie’s bones could be taken back to South Africa to be buried with his ancestors.

After Vernie and I scattered a handful of cold earth over Pinkie’s coffin, we looked at each other and, without needing to say anything, knew we didn’t want to be buried in Amsterdam.

The text on Pinkie’s funeral notice read: “You can take a man out of his country, but you cannot take the country out of the man.”

His bones were not brought home in 2000 and are still in grave N-III-0293. But he’s no longer the only South African in Zorgvlied, as the poet Elisabeth Eybers was buried there in 2007.

***

Something I haven’t properly touched on is Vernie’s activism. Many people use the word activist in conjunction with academic and poet to describe him, but that’s somewhat misleading.

Most activists, understandably perhaps, simplify issues and reduce them to black-and-white propositions; Vernie was predisposed to embrace complexity and paradox.

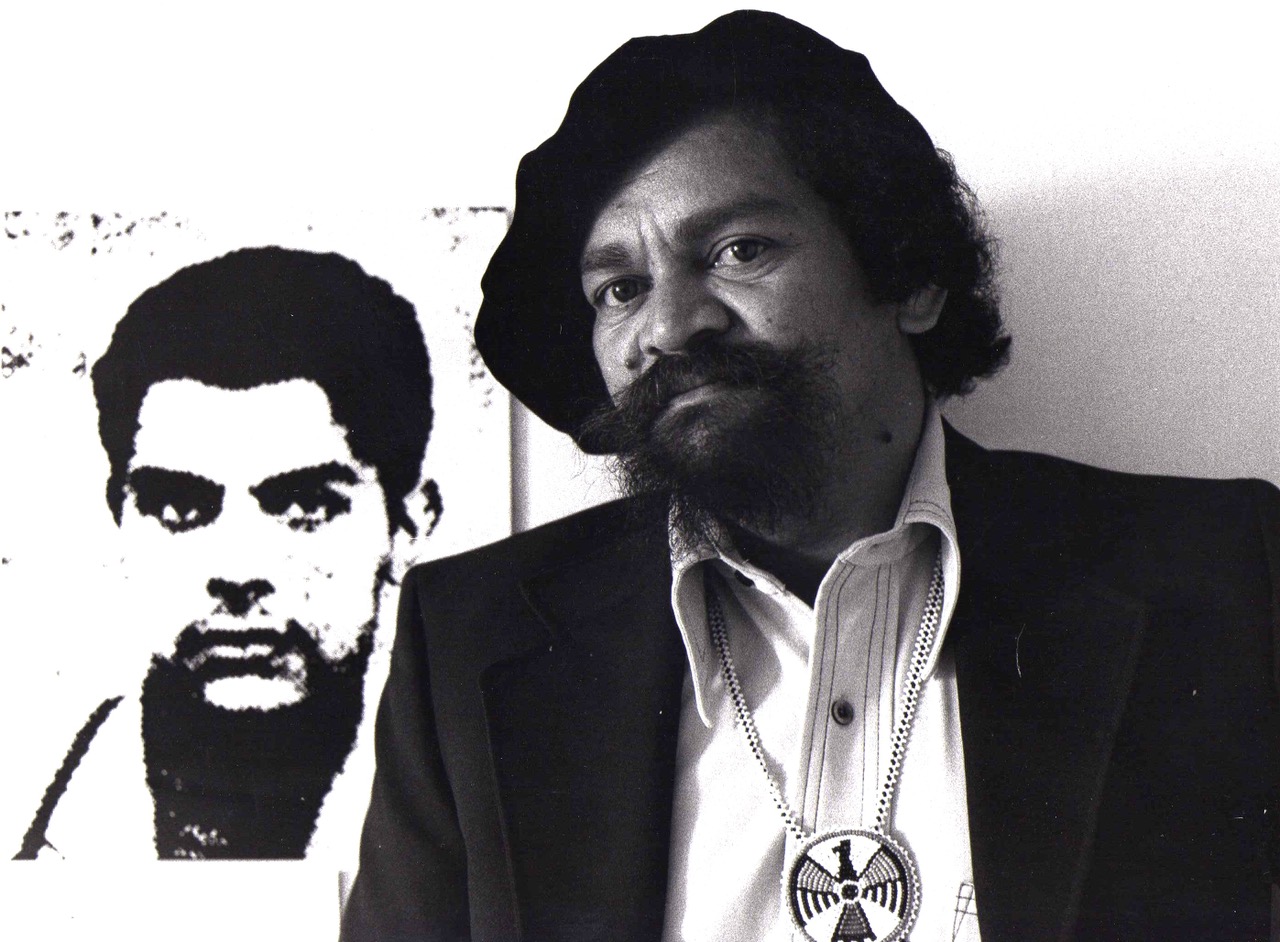

Vernie February next to the poster of his cousin Basil February, 1977. (Photo: Anthony Akerman)

He certainly had a strong ethical sense, deplored injustice, was humane, was prepared to stand up and be counted, and would read his poetry at public events and political rallies.

His house guests at Zoomstraat included the likes of Thabo Mbeki and Pallo Jordan – whose father Prof AC Jordan had taught Vernie at UCT – but Vernie wasn’t angling for a lucrative post-revolutionary sinecure.

He was the go-to guy when any of the several Dutch anti-apartheid groupings wanted to check the credentials of a literary figure.

In the 1980s, Leiden hosted a seminar on Sir Philip Sidney, the English courtier and poet who’d been killed in the Netherlands in 1586 at the Battle of Zutphen. Controversy flared up around this conference because the South African academic John Gouws – an authority on Sidney – had been invited to participate.

The Boycott Outspan Movement got wind of it, organised a protest and ensured Gouws was only given observer status.

Vernie phoned me one night laughing so uncontrollably that he could hardly get his words out. He eventually managed to tell me he’d received a call from an activist from one of these groups asking where Sir Philip Sidney stood on the issue of apartheid.

***

On 2 February 1990, I sat alone in my flat in the red-light district watching the BBC. I wasn’t expecting much, but by the time FW de Klerk had finished speaking, tears were running down my cheeks.

I ran up a ridiculous phone bill that day, drank more than was good for me, went to bed late, woke up with a hangover and regretted I’d agreed to meet up with Vernie so early the following morning.

In my notebook, I recorded: “We (he) spoke for hours.”

We were both slightly dazed and had stupid smiles on our faces. I’d been away for 17 years and Vernie for 27 – but now we could go home.

We had to resist the urge to pinch ourselves. By then I was also a Dutch citizen and, three years earlier, had been refused a visa. I planned to reapply the day after Nelson Mandela walked out of prison. It was hard to believe we were no longer exiles.

Change was in the air and many South Africans were passing through Amsterdam.

Later that month I met Jakes Gerwel at Vernie’s and attended a talk he gave in Leiden about the University of the Western Cape (UWC). I’d already booked a ticket to visit home in May when I was invited to direct my play, Somewhere on the Border, in Durban.

I’d recently been visited by Gerrit Schoonhoven, who’d directed the first South African production in 1986. Gerrit and artists like Johannes Kerkorrel were giving a voice to a new generation who defined themselves as “Alternative Afrikaners”.

Johannes – whose real name was Ralph Rabie – also looked me up. I had his album, Eet Kreef, and loved his song Hillbrow, although I’d only been there once when I was in the army.

Viewing the passing scene from the back of my bike, Ralph must have marvelled at how safe and laid-back Amsterdam was compared to Hillbrow. We cycled back to his youth hostel on Oudeschans.

As I picked up the heavy chain to lock my bike to the bridge railing on the canal, we were approached by a demented heroin junkie brandishing a syringe and making ungainly lunges in our direction.

“You wanna get Aids?” he screamed in Dutch.

My self-preservation instinct kicked in. There was a heavy padlock on the end of the chain and I swung it around and told him to get the fuck out of there or I’d hit him in the head. I meant it too. He eventually backed off and disappeared into the night shouting obscenities at us.

I may have given Ralph the impression I was the kind of guy who could hold his own on the streets of Hillbrow, but I was hyperventilating and badly in need of a stiff drink. That was the last time I saw him. In 2002 – when he was the same age as Pinkie – he also committed suicide.

***

In 1990/91, Vernie and I both spent extended periods in South Africa but our itineraries never intersected. He invited me to his inaugural lecture as a guest professor at UWC on 25 September 1991, but on that day I was on a flight back to Amsterdam.

When I walked into the arrivals hall at Schiphol, I asked myself rhetorically, “What the hell am I doing here?” I couldn’t come up with a good answer, so the next day I called a moving company. My friends organised a farewell party for me on 14 December.

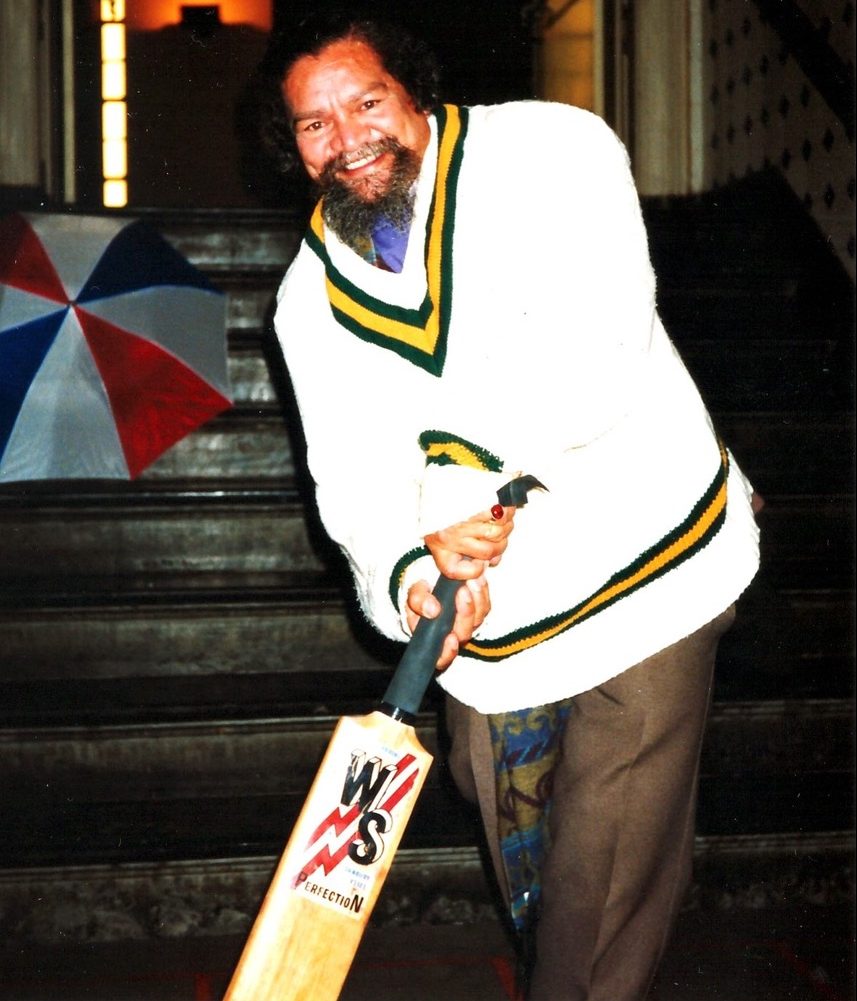

Vernie February at Anthony Akerman’s farewell party in 1991, still playing an away match. (Photo: Supplied by the author)

Although I found cricket terminally boring, I was given a cricket jersey by a friend in London and liked wearing something no one else wore in Amsterdam. That’s why one of my friends thought it would be amusing to photograph the guests in a cricket jersey as they arrived.

Vernie was back from Cape Town, as he still had work commitments that kept him in Leiden. When I looked at the photo of him at the crease, I realised he still had many away matches to play.

I was pleased to hear his daughter Rushika, now 21, had seen in the New Year with him and his family in 1993.

Life was getting better for Vernie, but over the next decade, we saw less of each other than we did in exile. I was based in Johannesburg and Vernie’s South African commitments took him to the Cape.

During the mid-1990s on a flight back to Amsterdam, he had to overnight at the airport. I drove out to the Kempton Park Holiday Inn and we all but emptied the bar fridge. Well, maybe that was me because Vernie was taking good care of his health.

In February 2001 he spent a few days with me while attending a conference in Johannesburg. This time I was the one who was between marriages. We reminisced about our hopes and expectations on 3 February 1990 when we talked for hours and couldn’t stop grinning.

Since then there’d been much to celebrate – but our new rulers had begun to show their true colours with Sarafina 2, the Arms Deal and Mbeki’s catastrophic Aids denialism.

Vernie had decided to take early retirement from Leiden University and, after 38 years in the Netherlands, return for good. He thought he’d be able to wind up his affairs by the end of 2002. When we said goodbye at what was then Johannesburg International Airport, I didn’t realise it was the last time we’d see each other.

We communicated regularly by email and he kept me informed about his plans. He obviously went off air for a while because, in September 2002, I received an apologetic email explaining his long silence. He and Esther had driven from Cape Town to Hankey in the Gamtoos Valley where, on 9 August, they attended Sarah Baartman’s burial. Nelson Mandela had formally requested the return of her remains in 1994 and France had finally acceded to that request, ending two centuries of shameful disrespect for her humanity. She was an exile who’d finally been brought home to be buried.

The road trip had taken it out of Vernie and, however solemn the occasion, he added, “the proceedings were even longer and sitting in that VIP tent was unbearable.” During the dinner he was taken to chat to Mbeki, now a president and no longer wearing the shiny Eastern Bloc suit he’d have worn when visiting Vernie in Amsterdam. I wondered whether he’d asked the president why beetroot, garlic and African potatoes weren’t on the menu.

When Vernie went back to his table, he told Esther he wasn’t feeling well. Then he blacked out. Fortunately, the president has a doctor in his entourage and Vernie was well connected. He was rushed to hospital in Humansdorp, then transferred to Port Elizabeth where he spent the weekend. They flew back to Cape Town and he saw his cardiologist. “I am taking it easy,” he wrote, “and will have to take my heart into account from time to time.” He added, “I have to be in Amsterdam between 13 October and mid-November in case you try to reach me.”

Before they left, I shared my big news with him. I’d met the actress/singer André Hattingh, we’d had a whirlwind romance and were engaged to be married. He replied, “I wish you all the happiness together for you deserve it, my friend.” Those were his last words to me.

On 26 November 2002, I received an aerogramme from Joseph saying he’d just visited Vernie in hospital. “He had a mild heart attack and blackout – but he is okay. I think they want to keep him in for observation. He can’t wait to be back.” When I put down the letter, the phone rang. Joseph had just heard Vernie died on the 24th.

I thought of the day we buried Pinkie in Zorgvlied and wondered if he’d also end up there.

A few days later I received an email from his daughter Naomi telling me they were bringing him home for burial. I couldn’t get to the funeral, but his niece, Judith February, who was there, told me it was Vernie’s express wish to be buried in Somerset West, in the shadow of the Helderberg.

She also told me that alongside Vernie’s grave is a grave where, two weeks earlier, Johannes Kerkorrel had been laid to rest.

***

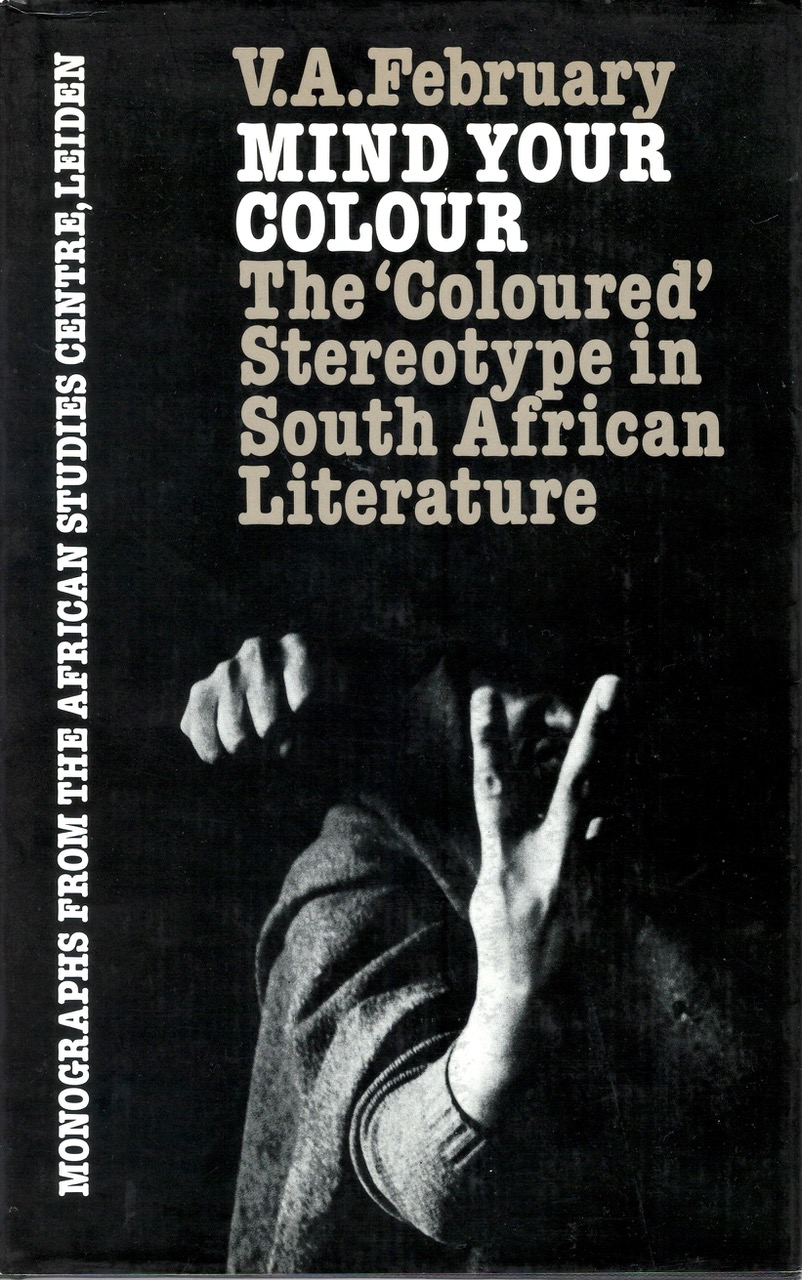

‘Mind Your Colour’ by Vernon A. February. (Photo: Supplied by the author)

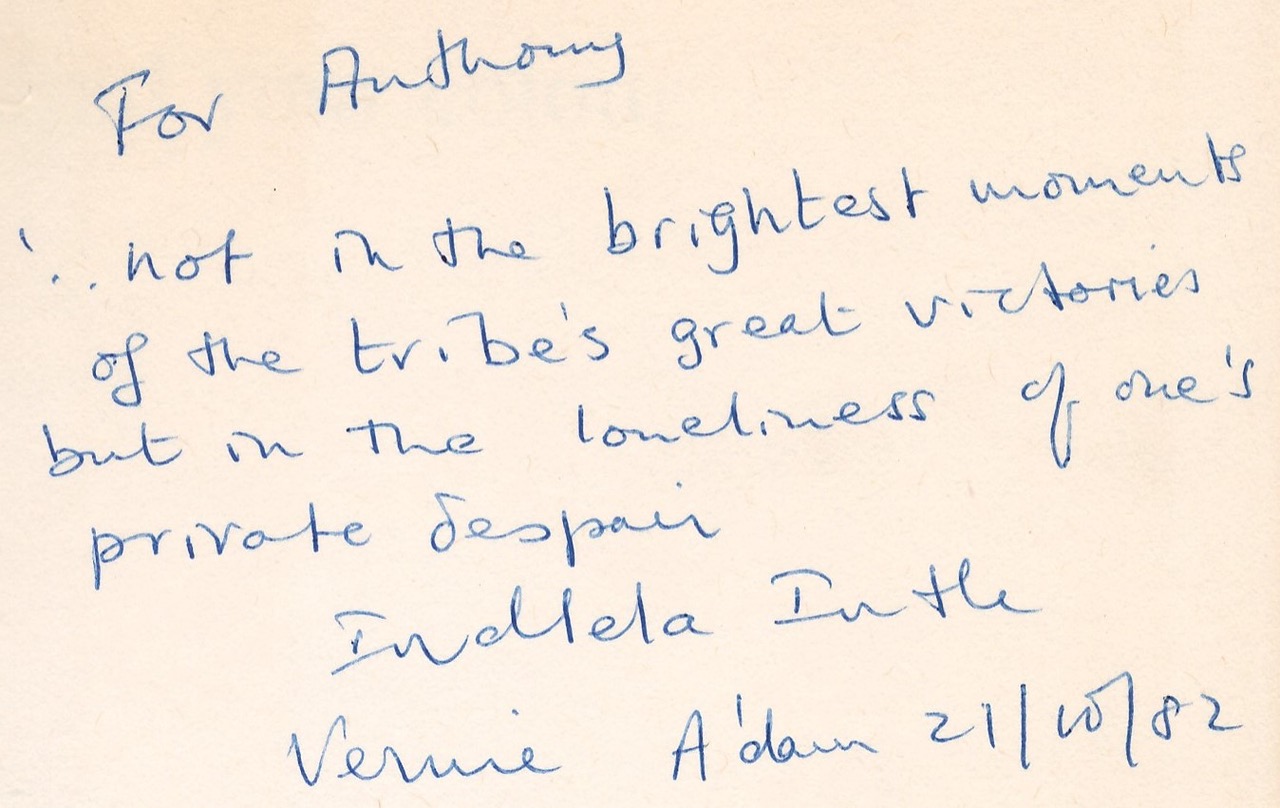

I recently opened my copy of Mind Your Colour and reread the inscription Vernie had written on the flyleaf over 40 years ago. I realised it was a quotation and wondered where it came from.

Had I asked him at the time, and he’d told me it was from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, I’d have looked as mystified as his supervisor did when he was first told the title of his thesis.

Vernon February’s Inscription in ‘Mind Your Colour’. (Photo: Supplied by the author, Anthony Akerman)

I don’t recall anyone talking about Campbell and mythic narratives in Amsterdam at the time. But, of course, Vernie had taught at Wisconsin University in 1978 and there was undoubtedly a revival of interest in Campbell in the US after George Lucas acknowledged that the structure and themes Campbell described in the hero’s journey had informed the narrative structure of Star Wars (1977). After that, many screenwriters used the hero’s journey as a template in the hope of similar success.

It’s interesting that Vernie chose a seemingly downbeat quotation referring to “the loneliness of one’s private despair”. It obviously resonated with the introspective poet in him. I looked it up so I could contextualise the quotation and it makes more sense with the two preceding sentences:

“It is not society that is to guide and save the creative hero, but precisely the reverse. And so every one of us shares the supreme ordeal – carries the cross of the redeemer – not in the bright moments of his tribe’s great victories, but in the silences of his personal despair.”

At the risk of sentimentally romanticising my late friend, Vernie’s life did follow the pattern of the creative hero’s journey. He left his familiar world, ventured into the unknown where he achieved great things, and, when he returned, he brought home something of enduring value. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a wonderful article. Thank you.

Excellent, thank you.

Such a nice read Anthony about an great human being and a close friendship.

Thank you. Lest we forget.

Thank you for this brilliant tribute!

Very moving story of friendship and exile. Anyone who has ever longed for their home county will resonate with this beautifully written article. Thank you. Also a little personal piece of the hidden history of some South African heroes.

Thank you Anthony lovingly written. A tribute to be shared with many who survived exile always to be scarred. For those who returned a second exile.

A wonderful read.