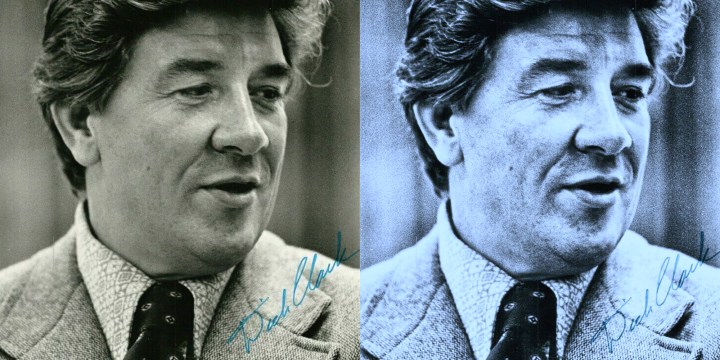

OBITUARY

Senator Dick Clark was a US politician before his time on southern Africa

Former Senator Dick Clark died last week aged 95. His efforts for just transitions in southern Africa while he was in the US Senate – and then as a senior figure at the Aspen Institute – should not be forgotten.

The narratives of change and liberation across southern Africa can be told, and too often are, with a simple set of broad strokes and the inevitable march towards the light. But along the way, the efforts of others can end up obscured owing to a focus on the brighter stars and comets. Dick Clark, the former US senator who died last week at the age of 95, is one of those less acknowledged, yet genuine, heroes.

In 1972, in the middle of the Nixon presidency, Nixon’s notorious southern strategy and his crushing defeat of George McGovern, the Democratic Party’s candidate for president, Clark had unexpected success as the Democratic candidate for the Senate from the state of Iowa.

His victory had come about in part through his folksy walk across the state where he met thousands of voters and spoke to them of their concerns about crop prices and taxes. His statewide walk echoed that of another recent, unlikely winner, Lawton Chiles, in his successful senatorial campaign in Florida.

Clark’s hardscrabble family background meant he was one of the first in his family to go on to a tertiary education when he earned a history degree from a local university, taught there and then became an aide to Iowa Congressman John Culver. When Culver decided not to challenge the incumbent Republican senator, Clark ran instead, achieving his unlikely victory.

Arriving in the Democratic Party-controlled Senate in 1973, he was appointed to the agriculture committee (a near must for a senator from a state like Iowa) as well as the coveted Senate Foreign Relations Committee (SFRC). But, as an unheralded freshman senator, he did not gain the chairmanship of any of the more influential subcommittees on the SFRC.

His only choice was to accept the Africa subcommittee, even though he admitted he had a scanty knowledge of Africa – and realised his Iowa constituents generally knew as little about the continent as he did and probably cared still less. Inevitably, corn, wheat, soya, pork and beef prices and markets were much more important to them.

During his single six-year term of office, a key legislative achievement for Clark was driving the establishment of the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, a new regulatory body for the trading of agricultural products, patterned after the Securities and Exchange Commission. But, in accordance with his SFRC subcommittee role on Africa, he soon threw himself into the study of African issues, even as they were often seen as the step-children of foreign policy amid the Cold War.

African issues

Clark began paying increasingly close attention to southern Africa’s circumstances. These included the ongoing civil war in Angola, the spiralling liberation struggle in then Rhodesia, and the seemingly rock-solid, apartheid regime in South Africa. On Angola, Clark visited the country, spoke to representatives of the government there as well as the rebellious groups in the north and south, as well as US government personnel there – including CIA personnel quietly aiding Unita.

For Senator Clark, the result became another piece of consequential legislation, popularly known as the “Clark Amendment”. It banned any further military involvement by the US in Angola’s civil war. The ban remained in place until it was removed during the Reagan presidency some years later.

Although the measure gained support in Congress in the aftermath of the bitterness of the Vietnam experience, Clark said he saw his amendment more as a way to separate the US from South Africa’s apartheid regime than simply a reaction to Vietnam. As he said about this: “The reason the amendment passed so easily in both houses was because of Vietnam, so I certainly related the two. But my interest was really in Africa and South Africa. We were aligning ourselves with apartheid forces. The reason for my amendment was to disassociate us from apartheid and from South Africa.”

It needs to be recalled that when Senator Clark pushed forward on this front, South African hegemony across the region still seemed largely unassailable – and it was coming amid the hardest years of the Cold War as well. Clark was showing an independence of thinking on African issues diverging from the prevailing orthodoxy of official Washington – and most especially about the tacit alliance between South Africa and the US. Then, contemplating the conflict in Rhodesia, Senator Clark pushed successfully to ban chromium exports to the US from the territory that had unilaterally declared its independence from Britain.

When Clark’s reelection race came up for the 1978 midterm election, the South African government saw Clark’s continued presence in the Senate as a serious threat – perhaps, ultimately, even for their continued existence. As part of the clandestine projects – later called the Muldergate scandal under Minister of Information Connie Mulder and his deputy Eschel Rhoodie, which had attempted to gain control over media assets in the US and South Africa along with other secret projects – they secretly took action against Clark. (The resulting scandal ultimately destroyed Prime Minister BJ Vorster’s career, but, ironically, Rhoodie ended up as a successful real estate broker in Atlanta.)

Regarding Senator Clark, a reported $250,000 of Department of Information funds were funnelled to a sympathetic public relations firm to be paid into the campaign war chest of Clark’s opponent, Republican former Lieutenant Governor Roger Jepsen. (Back in those pre-PAC and pre-SuperPAC days, a quarter of a million dollars in a senatorial campaign was real money for a Senate race in a small-population state.) One more irony was that one of Jepsen’s campaign jibes against Clark had been to speak about his opponent as that “senator from Africa”, rather than someone working for his constituents in Iowa. (The Jepsen campaign never admitted to knowingly receiving Muldergate money, although the PR firm never denied it outright before going out of business.)

Also during the election, the South African embassy had openly breached diplomatic protocol by getting directly involved in the campaign, asking voters during a diplomat’s visit to Iowa “why their senator finds South Africa such a fine platform, rather than dealing with the real problems this state might have”. The State Department dutifully lodged a protest, but Clark lost anyway.

On visiting South Africa, back when he was a senator, Clark discovered just how closely South Africa had been monitoring him. His itinerary had included a meeting in Port Elizabeth with Steve Biko, some months before he was killed. Clark said later that he became a kind of courier, taking a memorandum from Biko to Jimmy Carter’s incoming administration.

While he was in South Africa, Clark also met BJ Vorster and the prime minister spent an hour interrogating the senator on the full range of his public comments, including presentations at small colleges and universities scattered around the US. As Clark recounted the meeting, “He [Vorster] spent an hour with me. They obviously had followed me to each of these, much to my surprise. He would quote me. And then he would say, ‘Did you say that on such and such a date and such and such a place?’ We went through this for an hour. He just wanted the opportunity to tell me how wrong I was about everything I was saying.”

In 1978, Clark lost his re-election campaign, partly because of those jibes about him being the senator for Africa, but also because of his active support on women’s reproductive rights issues. Then as now, the question had some real political bite to it.

Special envoy

After his loss, President Carter made Clark his special envoy for refugees, addressing the circumstances of the many refugees trying to reach the US from Indochina, following America’s withdrawal that had brought the Vietnam conflict to an end. As a result, there were thousands of Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees, a large number of whom were desperately waiting in temporary camps around the Pacific in order to enter the US.

Despite the popular understanding that there are no second acts in American politics, rather than becoming a shill for some corporate association or an adviser to a powerful law firm, the former senator joined the Aspen Institute – a non-government policy studies and advocacy body, and he became their in-house expert on Africa. Over the years, increasingly aware of the possibility that violence could consume South Africa, Clark led Aspen’s efforts to build trust between the National Party’s apartheid government and the still-banned ANC – as well as to educate American legislators about the growing crisis.

Combining his interests in teaching and politics, Clark also launched programmes to educate members of Congress on foreign policy issues, setting up dozens of bipartisan conferences and retreats, including sessions on the politics and history of the Soviet Union, Vietnam and South Africa.

One such event, held in Bermuda in 1989, brought US lawmakers together with South African politicians and members of the country’s still-banned opposition. After Nelson Mandela was released from his incarceration, Clark organised one of those gatherings inside South Africa, this time bringing together delegations that included both Mandela and FW de Klerk. It may be hard to remember, now, just how difficult it would have been to carry out such efforts in a way that ensured discussion rather than rancour, given all the history and violence.

The Bermuda meeting allowed officials from the South African government to arrive quietly before still-outlawed ANC representatives could do so, especially since the latter was still operating outside South Africa. But as Clark said of that meeting: “All of them were there, making their pitches.”

Clark later wrote about his work with Aspen, saying it had “enabled me to help fill one of the most important needs of the US Congress: providing time and opportunity for informed reflection in a bipartisan setting. People have told me that this was more important than the work I did in the Senate. It may have been the most important thing I’ve done in my life”.

Dick Clark’s varied roles on southern Africa’s transitions largely remain remembered by historians of the region rather than the broader public. But beyond any contributions to achieving change in southern Africa, Clark’s efforts were important in pushing sometimes reluctant US government officials towards backing change and better understanding the dynamics of the region.

Thinking about Dick Clark’s efforts over decades should also help people understand that US government policies do not always come seamlessly out of monolithic government structures or decisions. They can also evolve from heated, sometimes even chaotic disputes over what should be done on any given issue. Further, decisions on foreign affairs are often subjected to a range of domestic pressures largely unrelated to the actual foreign policy questions concerned.

In today’s world, that realisation can help explain why aid to Ukraine may even become a kind of collateral damage in the increasingly acrimonious struggle over the US national government budget now playing out in Congress. True, many Republican legislators are less than enthusiastic about Ukrainian aid, but they are actually fighting about other budget issues — and among themselves over what positions their party will hold on government budgets.

In remembering Dick Clark’s legacy, we should recall his efforts in changing American policy towards southern Africa. But his larger legacy is also in the creation of mechanisms for members of Congress to explore issues and ideas in ways that would be even more useful today, given some of the angry, rancorous (and often wildly ill-informed) debates taking place in Congress now. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Interesting and well-written article. Thanks.

An informative and interesting article. Well worth reading.