SLAVE TRADE

Science filling in the gaps as St Helena’s lost history of slavery is uncovered

The occupants of a graveyard have added more to the hidden African stories of the slave trade on St Helena, thanks to DNA.

In a graveyard on the island of St Helena, the remains of a child buried with a copper bracelet offered a rare peek into the lives of a people whose history for so long has been untold.

The boy, perhaps ten or 12 years of age, was a slave most likely on his way to the Americas, when the ship he was on was intercepted by the British Royal Navy.

He didn’t live long as a freed slave. On St Helena, sometime between 1840 and 1867, he was buried with the copper bracelet that archaeologists suggest might have been an amulet to help him heal.

Such artefacts are extremely rare, but in this graveyard, archaeologists found beads, pieces of horn and iron bands, all objects that the newly captured slaves had somehow held on to, despite shake-downs by their captors, who would have stripped them naked.

Those discoveries were made between 2007 and 2008, ahead of roadwork and the construction of the island’s first airport. Now that graveyard and its occupants have added more to the hidden story of the slave trade, thanks to DNA.

Shackles used to control slaves in South Africa in the 18th century, on display at the Slave Lodge in Cape Town. (Photo: EPA / Nic Bothma)

Entwined histories

It is a story that entwines both the histories of South Africa and St Helena.

When archaeologists exhumed the graveyard they recovered the remains of 325 individuals.

After years of research, geneticists were able to extract and analyse the DNA from 20 of those individuals.

By comparing this ancient DNA with that of thousands of living people from across sub-Saharan Africa, the researchers have been able to infer where in Africa these liberated slaves came from.

The DNA suggests that they originated from between northern Angola and Gabon in West Central Africa. This ties in with the historical records of the time.

Centuries of migrations

However, lead researcher in the study, Dr Marcela Sandoval-Velasco, of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, warns that their results have to be considered in the context of modern geopolitical boundaries, and of nearly two centuries of migrations.

“We are taking two windows of time and comparing them to each other,” explains Sandoval-Velasco. “Populations don’t remain static, they migrate, meet, interchange and overlap. So it might be that these populations were not the same as they were 200 years ago.”

Still, the research does provide some insight into a dark period of history that historians have had difficulty piecing together.

In the US, the study of slave genealogies is notoriously difficult. Histories often only go back five or six generations before petering out on a plantation somewhere.

Lost are the stories of harrowing transatlantic journeys on slave ships and the African homes they departed from.

But advances in ancient DNA studies are changing this.

In early August, the results of a study was published that involved the extraction and analysis of DNA from the remains of 27 slaves that were exhumed from an African American cemetery near Catoctin Furnace in Maryland, US. Through genealogical website 23andMe, researchers were able to compare DNA links of the slaves to their modern-day descendants.

“It’s where archaeology, history and the hard sciences dovetail to produce these kinds of personal narratives of what the slave trade was,” says Dr Andrew Pearson, the archaeologist who led the team that excavated the graveyard on St Helena in 2007.

During the mid-nineteenth century, the Royal Navy’s West Africa squadron took the slaves they rescued from slaving ships and brought them to St Helena. The West Africa squadron was tasked with patrolling the west coast of Africa and intercepting slaving ships, as part of Britain’s initiative at the time to end global slavery.

The liberated slaves would then be taken to the African depo, a refugee camp set up on the island. It is estimated that 27,000 slaves passed through this camp, before being sent elsewhere.

“So a lot of the liberated slaves were either taken back to Africa, not necessarily where they came from, but to places like Liberia, which was largely founded by freed slaves, or to the British colonies in South America, like British Guiana, or the Caribbean,” explains one of the authors of the study, Associate Professor Hannes Schroeder, also of the University of Copenhagen.

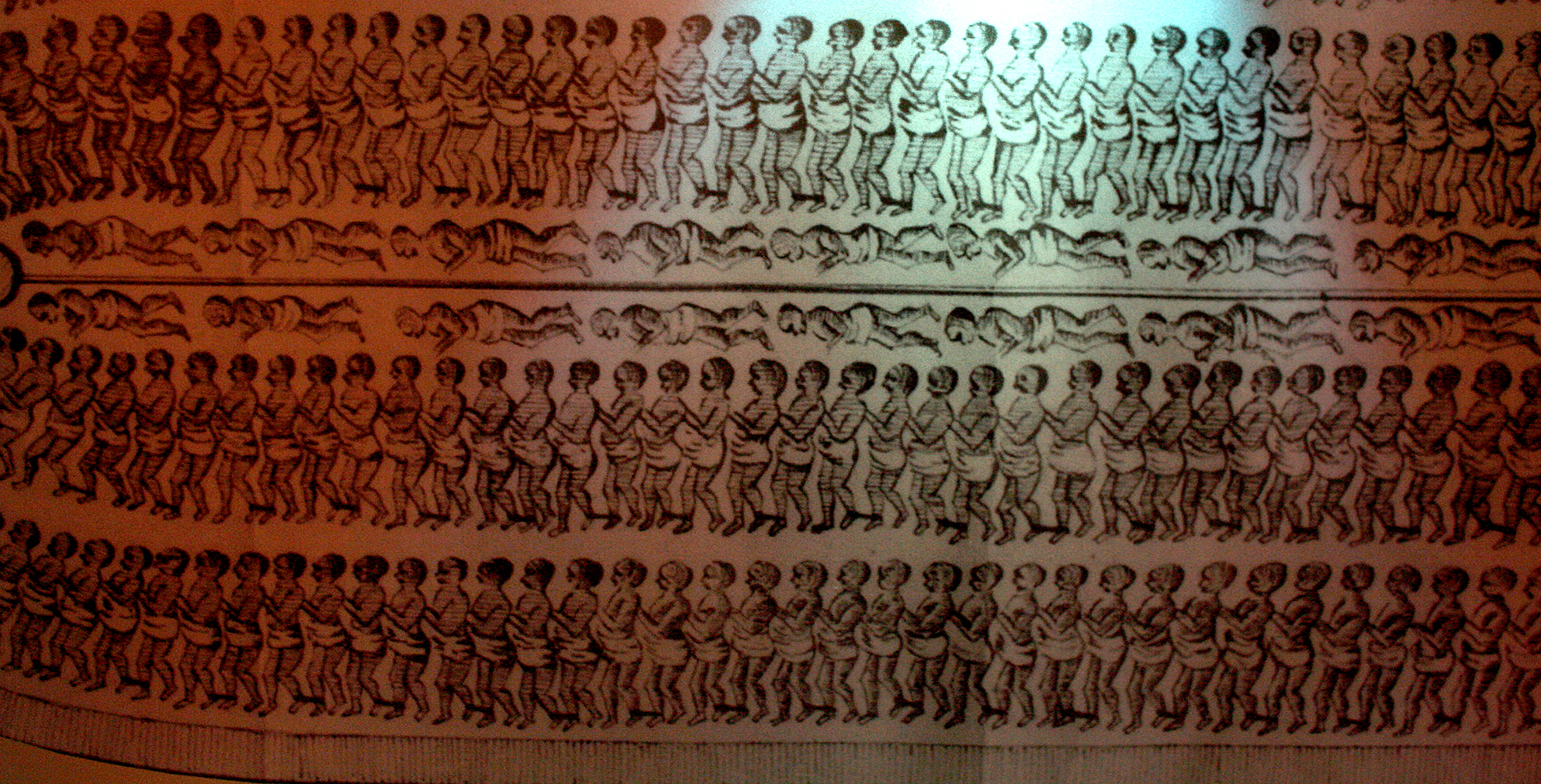

A plan drawing of an unnamed slave ship on display at the Slave Lodge in Cape Town. It showed around 400 slaves packed like sardines. They were being delivered illegally to Mauritius and Reunion in 1826, well after the British declared an end to the slave trade in 1807. (Photo: EPA / Nic Bothma)

Dead on arrival

Pearson believes that as many as a third of these liberated slaves died on St Helena.

Many arrived dead on the slave ships the Royal Navy had captured.

The mortality among the newly arrived just-freed slaves was so high, that Pearson believes graves were pre-dug and sometimes as many as seven individuals buried in one grave.

Now through their DNA, the story of these slaves has become part of a larger effort to understand the genealogical past of St Helena. It is a past that looms large in South African history.

During the South African war, Boer prisoners were sent to the island. Then there are those South Africans who have St Helena roots.

Historian Dr Damian Samuels, who is a St Helena descendant, believes there is a certain nostalgia among South Africans with St Helena heritage. Those who can trace their ancestry to the small island in the middle of the Atlantic refer to themselves as Saints.

There was a trickle of migrants who came from St Helena to South Africa from 1838, right up to Apartheid in 1948. “They settle in their own little communities and eventually marry into, you know, the broader coloured South African society,” says Samuels, who has studied the St Helena/South Africa connection.

In recent years genealogical sites have sprung up, like the Facebook page St Helena Genealogy, where South Africans log on to track down ancestors who once lived on the island.

However Samuels believes that the liberated slaves that ended up at the African depo, probably don’t have any South African descendants.

“Only about 40 odd of these slaves stayed and they integrated into the St Helenian population. But it was very difficult for them as they were usually the poorer people,” says Samuels.

Liberated slaves honoured

While their stay on the island might have been brief, St Helenians on August 20 last year honoured the 325 liberated slaves that were exhumed back in 2007. On that day they were reburied in coffins made by students from the local Prince Andrew school.

“This project was part of a larger ongoing effort by many people on and off the island to try and restore knowledge of St Helena’s liberated Africans,” says Helena Bennett, a co-author of the study and St Helena resident. “We hope that by telling their story, we can honour their legacy and ensure that their lives and fates are not forgotten.”

The work to fill in the gaps of the slave trade goes on. Sandoval-Velasco is now studying the ancient DNA of the slaves that ended up in her home country of Mexico.

“It gives me goosebumps thinking of how this discipline has evolved, and the possibilities we now have to tell past stories,” she says. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Who actually cares, apart from the odd nutty historian ? When is the past going to be left in the past ? Enough already. No matter where an archaeologist digs, he will find a trash heap because cities, ancient or modern, have trash heaps. Countries and geographies are the same, they all have buried skeletons. Perhaps it’s time historians started digging deeper into the slaving history of Africa because you can bet your bottom dollar Africa slaved as much as any other continent. Of course they won’t dig into Africa’s slaving history because it does not suit the African narrative and might undermine Africa’s chance at getting its little paws on all those shiny reparation dollars.