WRITING’S ON THE WALL

Tracing lines to a pre-colonial past by uncovering Mpumalanga’s rock art

Despite the richness of the paintings, Mpumalanga’s rock art is the most under-studied in the country, according to rock art researcher, Mduduzi Maseko, who is on a mission to unearth what the paintings reveal about South Africa’s pre-colonial past.

On the outskirts of the coal mining and maize farming town, Hendrina, Mpumalanga, amidst gentle slopes, pans, lakes, and sandstone outcrops are two rock shelters. Both are covered in layers upon layers of intricate red and yellow paintings: beautiful figures and forms that, for now, offer more questions than answers.

Mduduzi Maseko (29) is a rock art researcher determined to find out what these and other rock paintings in his home province of Mpumalanga can reveal about the region’s early past. Rock paintings vary widely. Despite the richness of the paintings, Mpumalanga’s rock art is the most under-studied in the country, according to Maseko. With hundreds of rock art sites across the province, some of them critically threatened by both legal and illegal mining, he has his work cut out for him.

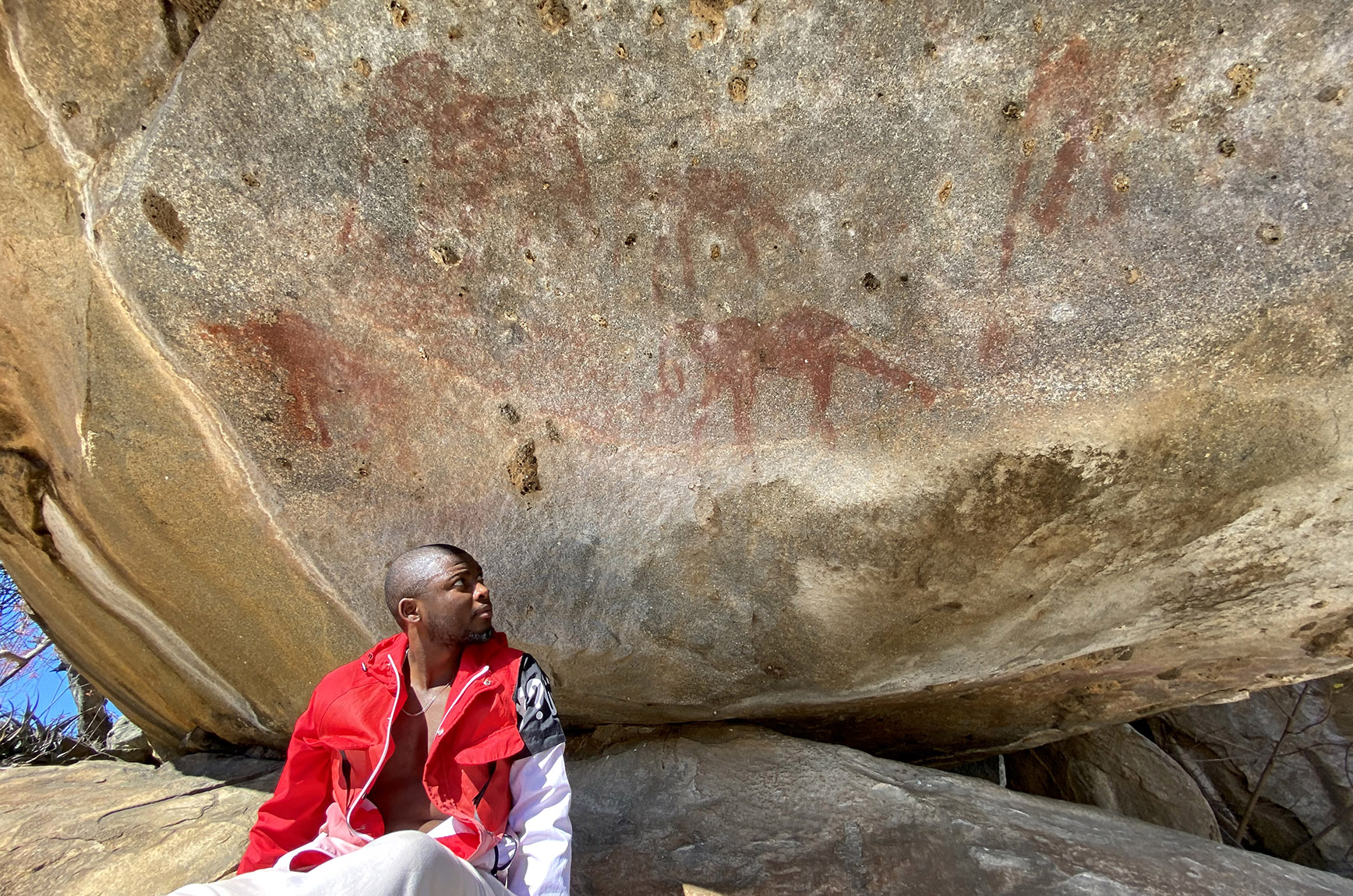

Mduduzi Maseko is a researcher with the Rock Art Research Institute at Wits University. (Photo: Supplied).

Maseko grew up in Empuluzi, close to the Eswatini border. He initially planned to study chemistry but discovered a passion for archaeology in his second year at Wits University. He realised that studying the material remains of long-ago societies offered a unique window into the vastness of southern Africa’s past and “that archaeology and concepts of spirituality, African spirituality were things that could coexist.”

Now, working at Rock Art Research Institute at Wits, the spiritual significance of the sites Maseko studies continues to shape his search for answers and meaning in rock art.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Letter from Mpumalanga — South Africa’s damaged paradise: Discovering the rock art of the Mthethomusha

Potent paintings

What makes the two rock shelters outside Hendrina striking is the sheer density of the images painted on their surfaces.

The people who chose to paint here didn’t choose shelters randomly but “these sites were painted over multiple times because they were recognised through generations as powerful and sacred spaces,” Maseko argues in his master’s dissertation focused on these sites and others in central Mpumalanga.

Making paint by mixing fat with ochres, iron oxide, charcoal, and perhaps clay, was inherently a ritual — the pigments themselves carried “spiritual potency”, Maseko explains.

Mduduzi Maseko is also studying the spiritual significance of the province’s rock art. (Photo: Supplied).

In the most striking shelter, the painters used red paint to create concentric circles, carefully filling dimples in the rock surface with colour and charting dense geometric lines, overlapping them with rows of dots by pressing their fingers covered with pigment on the rock. In the same bold red strokes, they painted abstracted symbols, including forms made of vertical lines and others that resemble people. If you look very closely, the faded yellow outlines of paintings of land are just visible from behind the densely painted thick red images.

A hundred metres away, not far from a waterfall, the second site spans 30 metres. It is covered in human and animal figures: three people, two feline-like forms painted in yellow, three elands, many other antelope, three dark red baboons, more animals, and what could be human-animal hybrids that can’t quite be identified. These figures are interspersed with, often painted on top of fine lined geometric shapes and tiny dot patterns.

In the eyes of an archaeologist, that all of these images are layered together makes them exciting. “If you look closely at what the images depict…closely at a rock art panel, then you realise there are these intricacies that can only be explained by looking at the belief systems of the people who made them and understanding their world,” says Maseko. With limited clues, this can be challenging.

A wealth of rock art

Maseko explains that archaeologists have divided southern Africa’s rock art into three different “traditions”: categories that are as contested as what to call the groups of people who made them and the colonial boundaries between them.

First, are fine-lined figurative paintings usually of humans, animals, or other beings. These paintings are typically associated with hunter gathers, pejoratively, but widely known as “bushmen”. Second, are the geometric patterns, finger dots, and concentric circles, either painted or engraved, that archaeologists believe were likely made by Khoe-speaking societies who practised herding. Finally, there is a tradition attributed to agricultural societies, with rough marks made usually with white paint.

The presence of all three of these kinds of paintings on the same rock surfaces around Hendrina complicates the neat categories that assign foragers, herders, and farmers each a different rock art style and questions the fixed and separated identities attributed to each of these groups.

A shelter near Hendrina, Mpumalanga showcases diverse styles of rock art on the same surface. (Photo: Mduduzi Maseko).

They could be “different traditions made by possibly the same people,” says Maseko. “Or the same site was used possibly by different people making different kinds of rock art.” His research so far can only speculate, but he emphasises that the fact that so many types of paintings were layered shows the sites’ enduring spiritual significance.

If the geometric paintings were indeed made by Khoe-speaking herders, it would add to the archaeological debates about Khoe identity and origins. But Maseko also points out that some of the rock art bears a “striking resemblance” to rock paintings much further north, above the Zambezi River where similar art is thought to be painted by foragers and farmers.

Mpumalanga’s forager past

For Maseko, the rock paintings’ connection with hunter-gathers is important to emphasise. “You don’t hear much about past hunter-gatherer societies in Mpumalanga, it’s almost as if they didn’t exist in Mpumalanga,” he says.

The presence of rock paintings in the landscape offers important evidence of a longer history of people who hunted and gathered in the grasslands of what became the province. Maseko explains that this is especially important because of the history of oppression and marginalisation of these groups during colonialism: “Knowing the history of Khoe-San people in South Africa, the genocide and all these other atrocities it’s very important to have that record.”

Clues from the Tlou-tle

In the 1950s, ethnographer Frederick Potgieter wrote The Disappearing Bushmen of Lake Chrissie. Like other racist anthropology of the era, Potgieter was fixated on the physical characteristics, especially stature and skin colour, of a group of people who lived in the area around Chrissiesmeer, in today’s Mpumalanga Highveld, who he wrote, “claim to be of pure Bushmen descent.”

Cognisant of the racism seeping the pages of study, Potgieter’s ethnography still offers Maseko important insight into the worldview of the Tlou-tle, one of a few distinct communities in Southern Africa considered to be Khoe-San who were still recognisable in the 20th century.

The sites of the rock art that Maseko studies overlap with places that are central in the social history of the Tlou-tle, who seem to have a long history in the area. Maseko writes that “there is a possibility that most of the rock paintings were made (if not by their ancestors) by people with a similar worldview”.

Cautiously, Maseko draws links between what ethnography on the Tlou-tle can reveal about the meaning of the rock art for the people who may have painted them. Most significantly, it shows that the placement of the rock paintings near water corresponds with the spiritual power of water for the Tlou-tle.

Many of the rock paintings Maseko is researching could have been made as early as 2000 years ago, or as recently as 200 years ago. It is challenging to date the paintings themselves and until more excavations are done in surrounding areas, there is no way of figuring out relative dates.

“It’s going to take years, possibly a few decades… before we get a more holistic picture of what the last 2000 years at least looked like,” Maseko says. These questions underlie the motivation for his PhD research, where he is returning to the same areas on the Mpumalanga Highveld to do excavations that will hopefully reveal when the paintings might have been made and give additional clues about the societies that made them.

Rock art and mining

The two rock art sites on the farm near Hendrina only came to archaeologists’ attention when “mining activities were expanding into the area, so it was now compulsory for heritage practitioners to go into the area and look at what is there,” says Maseko.

He continues, “I know of sites that have been destroyed because of mining activities. So, the fact that there has been so little that has been done in Mpumalanga is worrying in the sense that there might be a lot of sites that are being destroyed.”

Illegal mining also threatens rock art. Earlier this year, Maseko visited a rock site in the Blyde Canyon that is inhabited by Zama Zama miners who have drawn and scratched on the walls of the shelter and made cooking fires against the rock face, damaging the paintings.

Maseko explains that much of Mpumalanga’s rock art is on private property and that there are hundreds of sites scattered around the province (indeed all of southern Africa) that have not been documented.

To protect the paintings, the Rock Art Research Institute works to record as many rock art sites as possible, and people who know of the location of sites are encouraged to contact them via their Facebook page or Dr Sam Challis at [email protected].

As he continues to search for a fuller understanding of Mpumalanga’s rock art, for Maseko, archaeology is “a way of healing our generation, giving them that knowledge of this is where you come from, this is who you are, this is who your people were before colonialism happened”. DM

Note: The author’s brother, Simon Attwood, is an artist and independent researcher who has worked with Mduduzi Maseko in rock art research in Mpumalanga.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Great article Maru.

Beautiful, but demonstrably dishonest, and very much so. San people have almsot entirely disappeared from that area, the whole Kruger National Park etc. about 300 CE. Long before the arrival of European settlers. The genocide and racism words are comfortably thrown around but the wrong “arrivals from elsewhere” are blamed. The article should rather refer to Pre-Bantu Expansion/Arrival rock painting.