REFLECTION

The Dea(r)th of history and the price we pay in the present

Understanding the past, through the portal of history, is a life skill that is vital to the practice of democracy. Avoiding history undermines accountability and facilitates impunity. It denies us the opportunity to properly understand, and alter, the crises we face in the present.

Recently I had the privilege of moderating a conversation with globally respected public historian Adam Hochschild.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Adam Hochschild on history, storytelling and the prospect of a ‘South African dusk’

The conversation and the interest it generated – have caused me to reflect on the place of history in society and civilisation, and South African history and historians in particular.

It’s probably a misnomer to suggest that any one country has a richer history than any other, but South Africa’s is certainly rich and diverse. The problem is that it’s so incompletely and inconsistently recorded. Our country sits on a gold mine of characters and events, waiting to be rescued from its dark cavities and brought back to life for our present, in much the same way as Hochschild has done with the histories he recounts in his books.

Read more in Daily Maverick: ‘This is no mystery, we’re making history’: Celebrating the writings of Adam Hochschild

For example, on its website, the History Workshop, an interdisciplinary movement of academics established in 1977 to advance a progressive vision of public history in South Africa and now based at Wits University, says of Soweto – the “township” with the largest population in South Africa – that:

“Despite its prominence, Soweto’s history has not been chronicled in depth. The existing scholarship of the township has been limited to a few salient themes, being the student uprisings of 1976 and liberation struggles. Other publications include sociological analyses and biographies of leading political luminaries. Very little has been written on local histories of Soweto.”

As if to tantalise us with what’s missing and what’s possible, the latent power of history is borne out in several recent history books I have read that show what happens when historians do the spade work; André Odendaal’s Dear Comrade President, Oliver Tambo and the Foundations of South Africa’s Constitution; Jonny Steinberg’s Winnie and Nelson, Portrait of a Marriage and Koni Benson’s Crossroads, I Live Where I Like: A Graphic History.

They are very different books.

Adam Hochschild. (Photo: Amazon.com / Wikipedia)

Dear Comrade President is a meticulous examination of all the loose ends that led to the adoption of South Africa’s pioneering Constitution in 1996, demonstrating, says Odendaal, “the importance of African agency in the shaping of the Constitutional Guidelines and the making of the Constitution”.

Odendaal describes it thus: “The way in which South Africans constructed and formalised, politically and legally, a counter-hegemonic vision and a new Constitutional order is a remarkable story of African imagination, intellect, sacrifice and struggle, and success – even political genius – against huge odds.”

But Odendaal doesn’t just retell an existing story. His research – involving the pulling together of memories, minutiae and manuscripts – creates it. And he creates it not as a dry political narrative, but around the fallible human beings and their fraught relations that saw the Constitution through a century-long and painful gestation.

In Winnie and Nelson, Steinberg does the same through his painting a “portrait of a marriage”. By broiling the marriage back down to the human beings who were both products and producers of history, he is able to tell the story of an era. Although about the past, his book has much to reveal about the present.

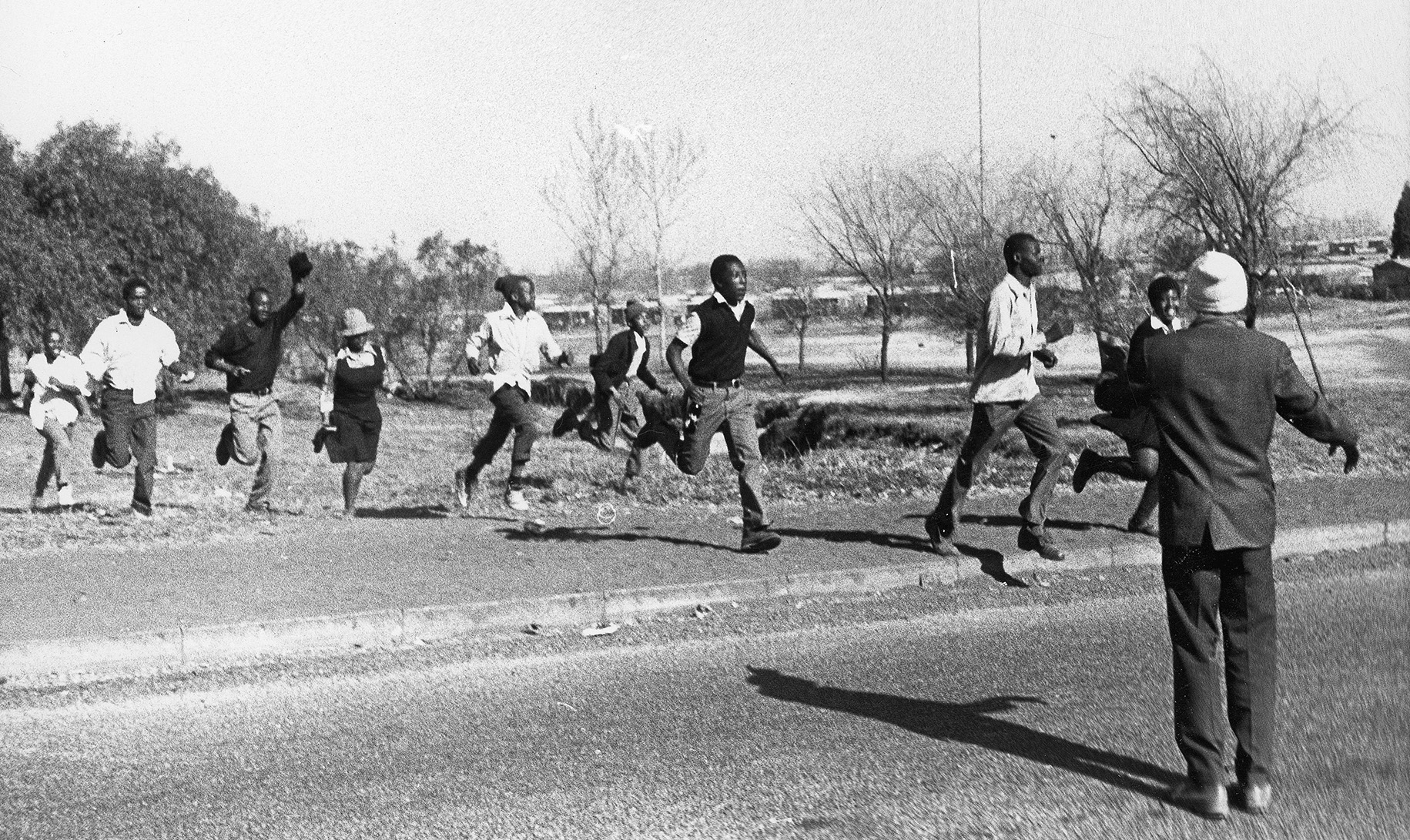

Students protest during the June 1976 uprising in South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

Intrinsic to the process of retrieving history are accidental discoveries that come about solely because making history is a search. Thus, while parts of Steinberg’s book are a thoughtful joining of dots of existing literature, his original account of Mandela and Winnie’s relationship while Madiba was in prison, based on police recordings of prison visits, owes much to his “discovery” of an attempt by apartheid’s last justice minister and prisons, Kobie Coetsee, to appropriate police records of Mandela’s time in prison into his own private library. This was a major heist – 15,000 pages – that Coetsee managed to hide until the papers were transferred inconspicuously to the University of the Free State after the death of his wife. Noting how apartheid officials “destroyed, stole and hid untold thousands of documents during South Africa’s transition to democracy”, Steinberg comments wryly:

“Had Coetsee not stolen the file, I am unlikely to have had access to it, certainly not in its raw, unredacted form. Although I myself played by the book and broke no law, I am a beneficiary of its theft.”

A history within history, a subplot that helps illustrate the themes of the main story.

By contrast, Benson says of her moving history of the community of Crossroads, a “squatter camp” in Cape Town, whose women-led struggles for democracy and social justice are almost a precursor for what later happened on the national stage, that: “By far the most important archive has been the people, as living archives, and the life narratives and oral histories produced with those involved in the organised movements of the struggles in and over Crossroads.”

In the very first chapter, she states bluntly: “African women in Crossroads have said that the history of shack dwelling in South Africa is the history of women.” As she unfolds her tale of how and why Crossroads was established, how women organised and were later subverted by men of all political stripes, you understand what she means.

Again, Crossroads suggests that there is a much wider set of histories that needs to be excavated, preserved and heard.

In each of these three histories, you can find forewarnings of our present in the past. Paradoxically, knowing history is a means to better foresight.

The beauty of these books is that out of patient, meticulous archival research and interviews, they join dots from our past that allow us to appreciate the rich texture of the present, and sometimes revise our understanding of the present.

We ignore historians and social scientists at our peril because they are the people who allow us to make meaning in the present, by showing us how this meaning has emerged from the past.

Without the discipline of the historian, things that happened, might as well not have happened; or at least we will never understand their influence. There will be black holes that swallow up people and processes, turning them into a drab canvas for lazy political generalisation, such as we have seen in the post-history narratives that are concocted around Nelson and Winnie.

In a foreword to the forthcoming Izibongo Zoogxa, the 10th volume in the series Publications of the Opland Collection of Xhosa Literature, Odendaal points to a fomenting of history and literary studies currently taking place in South Africa, mentioning academics such as Makhosazana Xaba, Khwezi Mkhize, Pamela Maseko and Athambile Masola.

He refers to “many new works now appearing” that “underline the point that South Africa’s intellectual history has for long been in need of fundamental revision as part of the broader liberatory project”. This “new wave of scholarship”, says Odendaal, “is part of a search for meaning and identities in the new context of democracy in South Africa”.

And yet – to me – this ferment and the academics and activists involved in it feel marginalised from the political discussions that shape our understanding of contemporary South Africa. Democracy and the future of civilisation depends on their endeavours, yet society does very little to recognise or resource them.

We ignore historians and social scientists at our peril because they are the people who allow us to make meaning in the present, by showing us how this meaning has emerged from the past. Social historian Ashwin Desai puts it this way: “History is a social art. At its core is the work of tying together the generations, of prizing human experience.”

The uncontrollable present

My reflections on South African history pose deeper challenges for us about what is happening in the present.

In 1990, Francis Fukuyama caused controversy when he wrote about “the end of history”. Funnily enough, he never actually declared “the end of history”, but that’s another story.

Protesters during the June 1976 uprising in South Africa. The Soweto uprising was a series of demonstrations and protests led by black schoolchildren in South Africa under apartheid that began on the morning of 16 June 1976. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

However, during a time when the present is suddenly moving very fast, and when the future leers at us with an unprecedented predictability due to revolutions in science, history is jumping up and down with its hands up, begging to be seen and shed light on what is happening in society. History gets it. It knows we cannot hope to understand or alter the destructive antagonisms that mark the present in a vacuum.

For example, the crisis in Ukraine has deep historical roots that rarely feature in any public discussion: the illegal invasion and war are not just taking place because Vladimir Putin is a very bad man, which he is.

The same can be said of the Trump phenomenon in the US. Media commentators scratch their heads about his abiding popularity even in the face of a growing list of criminal charges, but explanations can be found in books like Anne Nelson’s Shadow Network, or Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right.

Or, closer to home, liberal political analysts look at phenomena like the EFF and bemoan that race and identity are still so pivotal to South African politics, without even trying to understand the historical roots – so quickly glossed over in our political settlement – that feed anger at and alienation from white people’s enduring power.

Avoiding history undermines accountability and facilitates impunity. It seems we no longer care if some politicians have had a bout of genocide on their CVs, or a shady past with some incidents of peer-reviewed oppression or corruption. The weaker the historical memory, the less likely we are to be able to raise these things.

We need history! Yet at this moment it seems to me that what we are experiencing is the dea(r)th of history.

History features very little in political discussions or media analysis, and certainly not in informed decision-making. That’s not entirely surprising: history has been devalued at all levels of education and media; our archives, the repositories of history, are underfunded, undermaintained and left in wilful disarray.

Instead, we are encouraged to be a generation obsessed by everything that is shiny and superficial in the present.

All this ignores the fact that understanding the past, through the portal of history, is a life skill that is vital to the practice of democracy and understanding ever-shifting societal patterns. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

The children must lay a charge of abduction against the taxi driver at the police station. DS

I would like a historical account of life in the country from say 1901 to 1948(before apartheid was put on the books)

There must be research on that crucial period…? Maybe give Clarke’s Bookshop a call.

I saw a trilogy of Deneys Reitz’s three works, Commando, Trekking On and No Outspan at a local bookshop. This is from 1899 to 1943.

It is a personal account of the time, so might not be what you’re looking for. But these often are good to understand the people and times which a historical assessment might miss