THE PAST IS STILL PRESENT

‘This is no mystery, we’re making history’: Celebrating the writings of Adam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild’s public histories reveal to today’s activists – who often face danger and despair, sometimes loss of hope – that they are part of a proud, brave, imaginative tribe whose ancestry and pedigree go back hundreds of years. It is a tribe that, even in the worst circumstances, will not surrender its vision of human decency, dignity and equality. Ever.

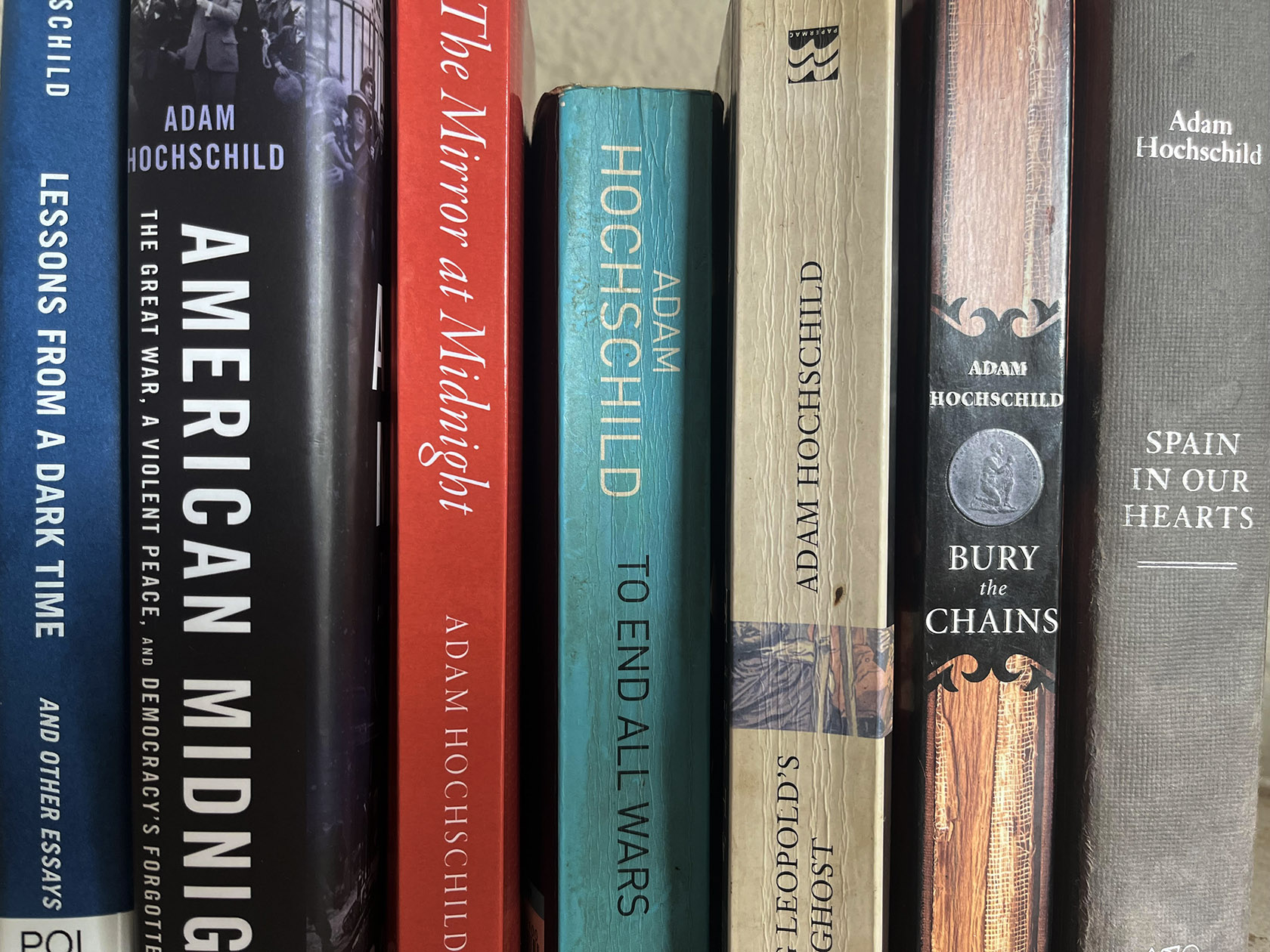

At the end of 2022 I became a happy owner of the latest Hochschild just in time to enjoy it over the holidays. I was probably the first person in South Africa to own one. What, you might be thinking, is a Hochschild? A painting, a poem, a novel?

Actually, it’s a nonfiction history book. But with a bit of each of the aforementioned, which is what makes it so enjoyable to read. In words quoted by Adam Hochschild in his 2008 essay on Practicing History Without a License, it’s a genre of “history that has the charm of literature”.

Adam Hochschild. (Photo: Book passage)

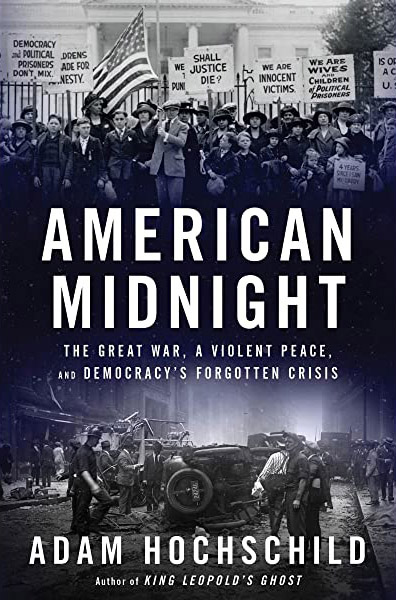

The latest Hochschild is titled American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis. It describes four dark years in the US, between 1917 and 1921, years which I think Hochschild thought held a similar dark portent to the Trump presidency. However, in a recent letter he told me that since writing the book, he had been feeling “a little better about things in the US than I did before our recent elections, but we still came very close to midnight two years ago, and that could well happen again”.

In history a lot can happen in four years (and did in those years), which makes it hard to justly summarise the book’s arc. As usual Hochschild brings history to life around a cast of characters and a storyline that will not be familiar in “traditional” histories of the period. But it is by no means invented.

It’s about the people who were fighting for a fairer and more just America before its entry into World War 1; people who resisted the war and who were calumniated, beaten and imprisoned: activists such as Emma Goldman, John Reed, Eugene V Debs, and WEB Du Bois to name but a few. It’s also about the people who harassed, imprisoned and exiled them.

American Midnight meticulously excavates one of the country’s darkest moments, a time when “human empathy seemed to shrink” and racism, antisemitism, classism and ultra-nationalism were allowed to rule the roost.

Sound familiar?

Hochschild often ends his books with a chapter that reflects back on the story he has narrated, in this case noting: “The American Socialist Party would never recover from the mass jailings and the crushing of its press that took place under [Woodrow] Wilson. Had it not been so hobbled, even with a minority of voters, it might well have pushed the mainstream parties into creating the sort of stronger social safety net and national health insurance systems that people take for granted in Canada and Western Europe today. This is one of American history’s most tantalising ‘what if?’ questions.”

It is indeed. Just as 10 days in Russia in October 1917 shook the world, these four years in American politics shaped the following century.

People walk past an exhibit about the 1912 Presidential Election which featured four candidates in which Theodore Roosevelt ran as a Progressive, William Howard Taft as a Republican, Eugene V Debs as a Socialist, and Woodrow Wilson as a Democrat at the new exhibition “Democracy Plaza” at Rockefeller Center 20 October 2004 in New York City. (Photo: Mario Tama / Getty Images)

Colonialism and its discontents

American Midnight is the latest of eight works of history, plus a couple of books of essays, written by Hochschild, since his first public history, The Mirror at Midnight: A South African Journey, was published in 1990. That book was an outsider’s take on our own transition from apartheid and colonialism to democracy: “three hundred years that makes achieving real change in South Africa far more difficult than it first appears”.

It is affirming to “we, the people” of South Africa that one of the world’s greatest public historians has a special relationship with our country. His experience interning with an anti-apartheid newspaper in 1962 (described as “momentous and life-changing” and providing him with a “moral touchstone”), and his return as a journalist for a few months in 1988, seems to have inspired his mission to uncover and narrate history by exploring the interface between social activists and social justice. His personal and historical journey started in South Africa whose conflict he described as “about something much larger than the fate of a single nation at the other end of the world. South Africa seems a moral battleground as well as a physical one and a battleground that poses choices for other nations as well…”.

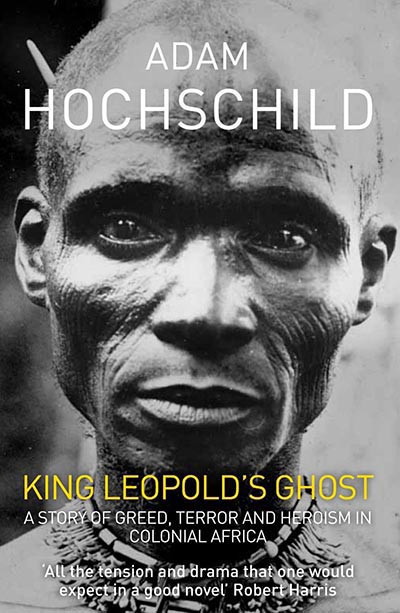

This makes it apposite for me that, back in 2001, in the midst of a bitter struggle that was to define the Treatment Action Campaign, activist Zackie Achmat was the first person to put an early Hochschild in my hands: the great book King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1998).

In his dedication Achmat described it as a book “that shows the struggles against colonialism, exploitation and racism and rips the mask off refined evil”.

I read it voraciously. It is a magnificent evocation of memory against forgetting, documenting the horrors inflicted by King Leopold and the Belgians on the people of the Congo, and of the bravery of the Congo Reform Association.

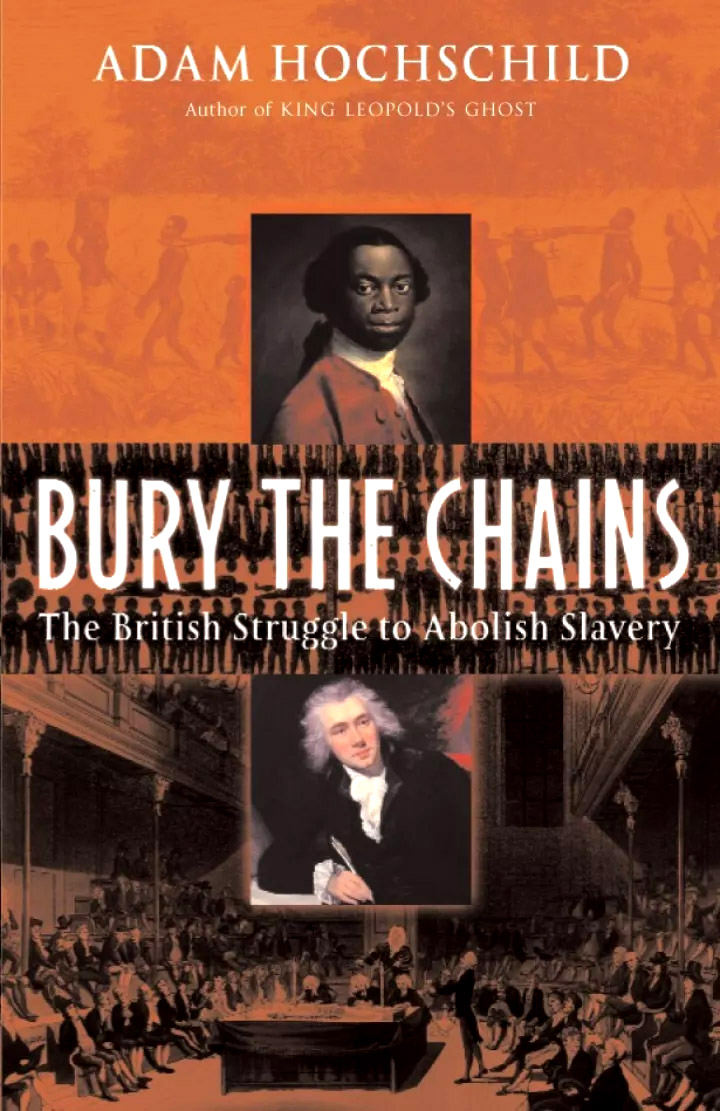

However, reading King Leopold’s Ghost was to be the start not the end of my relationship with Hochschild. A few years later he published what I consider to be his greatest work – Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves. The power of this book is that it is the story of the world’s first social justice campaign – to end slavery.

Hochschild’s pen unfolds a gripping drama. But the story’s power lies in the way it demonstrates (again) how a few unlikely individuals, not even considered by themselves as “activists”, started a movement that catalysed profound global change.

For example, many might know the name William Wilberforce, but who has ever heard of the nerdy Oxford philosophy student, Thomas Clarkson, the son of a lowly clergyman, who in 1785 chose to enter a Latin competition at Cambridge with an essay about the slave trade? His research revealed things that so shocked him (“I sometimes never closed my eyelids for grief”, Clarkson wrote) that he had to ask himself “Are these things true?… Then surely some person should interfere”.

And “interfere” he did.

According to Hochschild, as a result of Clarkson’s empathetic awakening, “If we were to fix one point where the crusade (against slavery) really began, it would be on the afternoon of May 22, 1787, when twelve determined men sat down in the printing shop at 2 George Yard [in London]”.

At that meeting, according to a set of minutes that survive “it was resolved that the said Trade was impolitik and unjust” – an understatement that launched a global movement, recorded on a piece of paper that has survived the centuries.

Hochschild argues that the campaign they catalysed against slavery “was the first time a large number of people became outraged, and stayed outraged for many years, over someone else’s rights. And most startling of all, the rights of people of another color, on another continent”.

Following on that afternoon in 1787, what captivated his imagination was how, “in the 1780s, the early British abolitionists invented virtually every organising tool I had seen used in the movements against segregation, the Vietnam War and apartheid: the political poster, the campaign logo, the consumer boycott, the very idea of an organisation headquartered in a national capital with branches around the country. I was fascinated by these remarkable organisers and wrote a book about them”.

But what I find most remarkable about Bury the Chains is that the human rights activism it describes took place in a time before electricity, the telephone, the aeroplane, mass media and obviously email and the internet.

“There is always something mysterious about human empathy, and when we feel it and when we don’t,” writes Hochschild in Practicing History Without a License. “Some of the most interesting moments in history are when there seems to be a sudden leap of empathy.”

At that distant moment, the “sudden upwelling [of empathy] caught everyone by surprise. Slaves and other subjugated people have rebelled throughout history, but the campaign in England was something never seen before…”.

Nonetheless, he warns, history also teaches us how “every system of oppression is tenacious and all too often reorganises itself into something similarly nasty under a different name”.

Generations of black Americans would nod their heads in agreement. So too would many South Africans.

The importance of public history

Since reading Bury the Chains I have assiduously recommended Hochschild’s books to activists I encounter seeking to change our world. I have also waited patiently to relish each new offering: To End All Wars: A Story of Protest and Patriotism in the First World War (2011), Spain in our Hearts, Americans in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) (2016) and others.

The past is important to the present, and fortunately South Africa too has some notable public historians cut from the Hochschild cloth: starting with Sol Plaatje, HIE Dhlomo, Peter Delius, Noel Mostert, Luli Callinicos, André Odendaal, Koni Benson, Noor Nieftagodien and Martin Legassick, to name a few. They have a rare skill, but we pay them insufficient attention. We owe to them, and others of this tribe, the ability to rescue significant moments, and the people who made them happen, from oblivion.

Sometimes this takes place several centuries after they have passed, and depends on meticulous archival research, extant letters, existing histories and contemporary interviews to join the dots.

It requires that the historian enter into the spirit, not just the letter, of history.

So here’s the rub. Public history is not pulp history. As Hochschild says in his essay Practicing History Without a License, “there is no reason why history cannot be written in a way that offers thought-provoking analysis and at the same time reaches well beyond an audience of fellow scholars”.

It has a method and a discipline, although its shape may vary: “The historians who know their subjects deeply must also learn to wield the tools of … the dramatists. The historian’s job is to use the classic narrative devices of plot, character and scene setting to tell a story – but without getting so seduced by the tools themselves that the story gets distorted.”

And there’s a reason for this. History has a public purpose in the present, something Hochschild evokes in a description of South Africa’s Constitutional Court building, which, he says, “is public history at its best: taking the bricks of the past and using them to build something solid for the future”. (You Never Know What’s Going to Happen Yesterday, 2010).

But ultimately, Hochschild shows us how history is all about the people, not the flotsam and jetsam of official politics and venal politicians.

(Image: Karibaa)

For example, in American Midnight, he records how after the end of World War 1, US President Woodrow Wilson refused to pardon the Socialist leader Eugene Debs, even though from prison Debs had won 900,000 votes in the 1920 presidential election. Debs’s response was: “It is he, not I, who needs a pardon.”

This vignette of history points to an important difference that Hochschild brings to public history: his books are invariably about the defiance of activists who really shaped history, unearthing an invisibilised current that never ceases to push against the stream during otherwise quite well-known moments and episodes in history.

His histories reveal to today’s activists – who often face danger and despair, sometimes loss of hope – that they are part of a proud, brave, imaginative tribe whose ancestry and pedigree go back hundreds of years. It is a tribe that, even in the worst circumstances, will not surrender notions of decency, dignity and equality.

In the concluding lines of To End All Wars, a book about the resistance to World War 1 in England, he asks us to call to mind an “imaginary cemetery … of all those who understood the war’s madness enough not to take part”.

“This,” he says, “would be a cemetery not of those who were confident they would win their struggle, but of those who often knew in advance that they were going to lose yet felt the fight was worth it anyway, because of the example it might set for those who might someday win. ‘I knew it was my business to protest, however futile protest might be,’ wrote [Bertrand] Russell decades later. ‘I felt that for the honour of human nature those who were not swept off their feet should show that they stood firm’.”

In To End All Wars, Hochschild was reflecting back on World War 1 “after a century’s worth of bloodshed after the war that was supposed to end all wars”.

Today, although an American Midnight may have been avoided (temporarily?), a global midnight of unbridled war and climate crisis today inches closer and closer. In this context, it is reassuring that although activists’ methods may be different, and technology has transformed their tools of trade, they start from the same sense of outrage and are driven by the same vision of justice that Hochschild’s histories tell us about. DM/ ML/ MC

Coming soon: A Daily Maverick webinar with Adam Hochschild in conversation with Mark Heywood.

I’m off to further investigate Hochschild’s writings!