WATER-RELATED HEALTH CRISES OP-ED (PART ONE)

Cholera — have we really learnt nothing from Covid-19?

The first of two articles examining water-related health crises in South Africa asks why we have learnt nothing from previous crises and why our government, having responded to each new crisis with the same or similar pledges arising out of previous crises, ignores the pledges once each event is over. This is Part One of a two-part series.

South Africa’s response to the current cholera outbreak suggests we’ve learnt nothing from the shock, disbelief, fear and anger with which we responded to Covid-19.

“We are at war,” Cyril Ramaphosa announced in June 2020, a little more than two months after declaring the national Covid-19 lockdown. He explained: “We are fighting a life-and-death war. Cost is not the issue here; saving lives is the main issue.”

Left unsaid was whose lives were being saved.

What meaning can “saving lives” as the main issue have had for the homeless expected to remain housebound; or for the often large numbers of people — especially children — living in small homes; or for the millions whose homes are shacks that, at best, provide little more than minimal protection from the weather?

Read more in Daily Maverick: Hammanskraal cholera outbreak

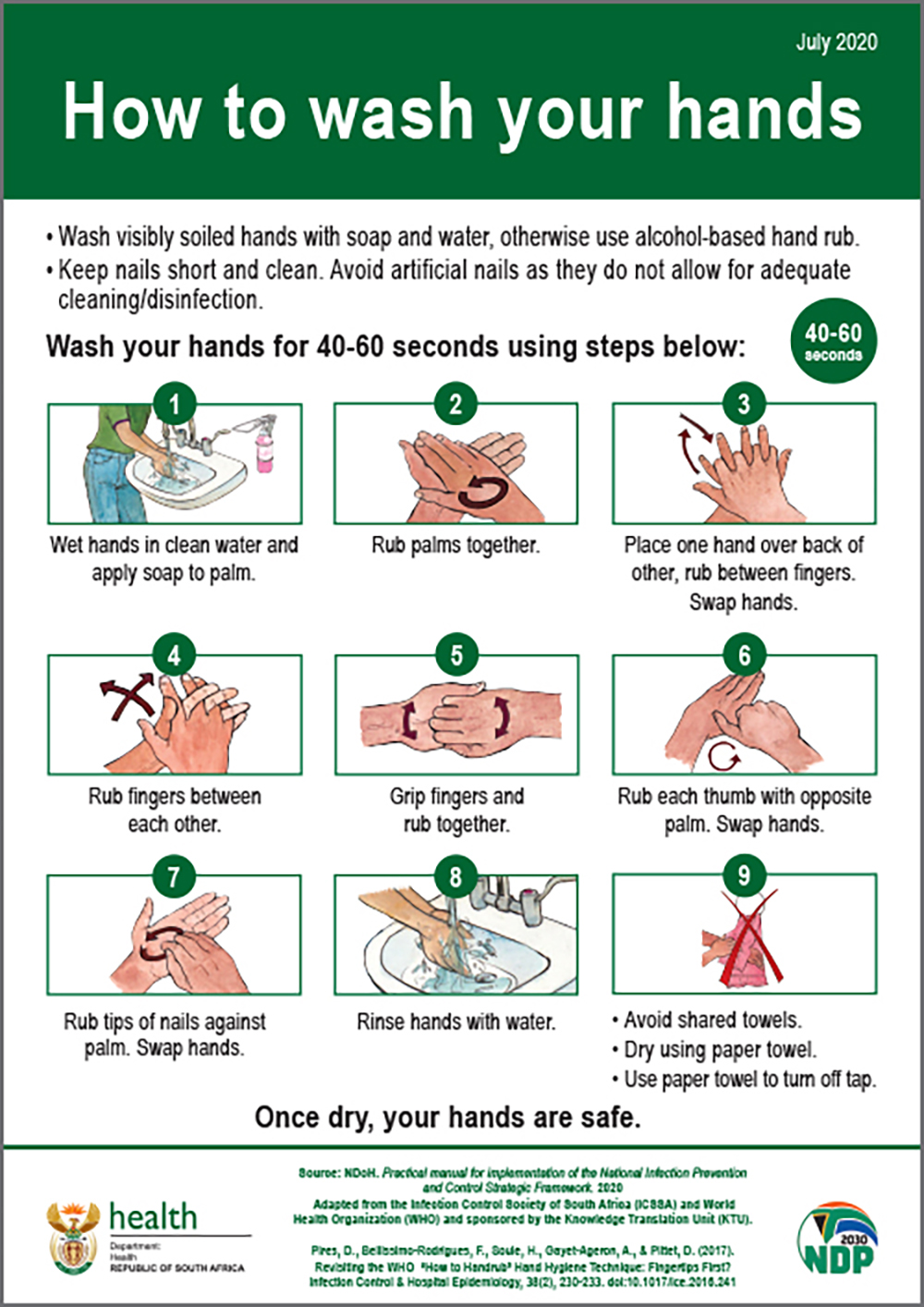

How was physical distance in the townships and slums, or in the taxis transporting essential workers to be maintained? Or handwashing to be carried out without water, whether because of not being connected to the municipal supply; or when that supply is not available; or when the advised handwashing routine exceeds the total daily free water supply, even for the small number of people who succeed in being registered as “indigent”; or when the price of water makes only a grossly insufficient amount affordable to most people? How were people to buy facemasks and sanitisers when they could afford little more than their poverty?

These questions link to two that recur — mostly implicitly — throughout the first part of this two-part article: Why have we learnt nothing from our experience of previous crises? Why does our government, having responded to each new crisis with the same or similar pledges from previous crises, then ignore the pledges once each particular crisis is over?

Why, indeed, should we be in the least startled by the current cholera outbreak? The only unknowns were the specificities of where and when it would occur — or the name by which it would be known. Hammanskraal turned out to be the name for the present epidemic. There were no other unknowns; everything else was known — and known in detail. The government knew it; Parliament knew it; water and health specialists knew it. Activists knew it well.

‘Large-scale system breakdown’

Hammanskraal is already well known for being more than just a water and sanitation problem. Alexander Parker, Business Day’s editor-in-chief, knows Hammanskraal’s full meaning: “In our broken state, cholera is the symptom, not the disease.” The resurgence of “old illnesses” — measles, mumps, diphtheria and chickenpox — is the evidence, Parker warns, that “most people are wholly exposed” to this “large-scale system breakdown”.

It is this circumstance that, like the sacrificial canary in the mine, takes Hammanskraal well beyond its particularities. The tragedy of the Hammanskraal deaths and sufferings is compounded by the lessons not learnt from previous cholera outbreaks.

Nurse Florence Kgwarere talks to Amos Mmakou, a patient recovering from cholera in May 2023 at Jubilee District Hospital in Hammanskraal. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

The largest cholera event in South Africa’s history is the now often-forgotten one that broke out in KwaZulu-Natal between August 2000 and August 2001. The event in the Eastern Cape in 2003 provides still further reminders of the barrenness of the reassuring pledges made during public health crises.

The 2003 outbreak also prompted a sustained involvement by the South African Municipal Workers Union (Samwu); before that organisation had succumbed to the national cancer of corruption.

Roger Ronnie, the then general secretary of Samwu, wrote a long article published in late 2005. The article was written in response to the outbreak of typhoid — another water-related illness — in Delmas, in early 2005. It began:

“The long-predicted disaster has happened — yet the government and officials, who were among those quick to reassure the public about the safety of our water, now feign shock and horror while expressing sympathy to the typhoid victims and pointing fingers at others.”

Having noted a number of occasions when the then minister of water affairs and forestry and others in her department had made passing references to unsafe water, Ronnie notes a single paragraph in the second draft of the department’s first National Water Services Regulation Strategy of September 2004. The document makes the dire warning that:

“Recent surveys of drinking water systems have shown that a significant percentage of these systems do not meet the national minimum standard. There is therefore a significant risk that unsafe drinking water supplies could compromise the health of consumers and possibly even lead to deaths.”

The warning was removed from the published version of the regulation strategy.

The refusal to make public the frightful state of our water came some eight months after Dr Kevin Wall, of the CSIR, made public the real state of our water service. He did so during his presentation at a breakaway session at a two-day water conference in February 2005. Ronnie’s article reported that Wall,

“presented a devastating critique of our water and wastewater treatment plants, along with shocking photographs of unconscionable neglect and mismanagement”.

Senior officials, including the then director-general of the Department of Water and Forestry (Dwaf — now renamed the Department of Water and Sanitation, DWS) — were present throughout Wall’s dumbfounding presentation.

A tanker delivers water to residents of Hammanskraal during the cholera outbreak in May 2023. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

The presentation so shocked Samwu that, as Ronnie recounts in his article, the union wrote to the Dwaf DG. Noting that Wall’s evidence amounted to a national crisis, Ronnie suggested that the issue was far bigger than the Dwaf. Samwu accordingly called for all appropriate government departments, along with trade unions and other organs of civil society to get together to discuss what could be done.

“Our intervention fell on deaf ears,” Ronnie records of this February 2005 exchange with the most senior official in the water department. The final paragraph of Ronnie’s September 2005 article reads:

“DWAF ignored Samwu’s first call for a national response to the national crisis posed by unsafe drinking water in many parts of our country. With DWAF’s own worst predictions having now been realised, Samwu repeats this call.”

It, too, was ignored.

Water becomes a central issue

And then came Covid-19, many crises later. As though for the first time, water became a central issue. In the context of suddenly recognised inequality, water’s availability, quality, quantity and affordability were rediscovered. So too were dysfunctional municipalities and their inadequate senior managers, to say nothing of corruption. All this was in 2020.

For Lindiwe Hendricks, who was water minister in 2007, protecting senior water managers and, by extension, the municipalities that employed them, was of much greater concern than the water problems faced by most people. As reported in the media in May 2007, she indicated that no action would be taken against water-polluting municipalities without first building their capacity. The absence of managerial and technical capacity, she claimed, made law enforcement premature.

Samwu’s new general secretary, Mthandeki Nhlapo, challenged the minister’s selective and unauthorised abandonment of law enforcement. Expressing disbelief that the minister could be saying that no action would be taken against water-polluting municipalities without first building their capacity, he, in a piece published in the Cape Times, asked:

“What level of harm must be done before the Minister and her Department stop hiding behind alleged capacity problems?”

Constance Ngobeni, a resident of Hammanskraal, with clean drinking water she had to buy in May 2023. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

Their guiding principle was what they called a “softly, softly approach” to managerial incompetence. This was part of their “developmental approach” to assist new, inexperienced or incompetent managers. The private companies contracted to assist them supported this position, saying taking disciplinary action was pointless as there were no other suitable people to replace them. Picking up this theme, Nhlapo noted:

“The Minister talks about the absence of capacity rather than the absence of managers. The difference is important. The appropriate management posts are filled, and the incumbents receive salaries that have shocked the public by their size. But the managers, who are happy to pocket managers’ salaries, don’t have the capacity to do the managerial work for which they are paid! Worse still, even though public health and the environment are placed in serious jeopardy by their incompetence, the Minister of Water says we must all be patient.” (Mthandeki Nhlapo, “Capacity does exist”, Cape Times, 21/5/07)

Nhlapo also drew attention to the blatant double standard involved when disciplining ordinary workers. “Wouldn’t it be nice,” he noted, “if ordinary workers were treated with the same sensitivity and forbearance! Instead of such tolerance, workers who don’t have the capacity for the jobs they occupy are sacked — often by the very managers the Minister is so eager to defend.”

Nhlapo additionally addressed the problem of the so-called capacity deficit. As part of the policy of making space in the department for the apartheid-excluded, he reminded the minister that the capacity problem was largely self-made. Experienced managers and skilled workers were encouraged to establish their own private companies which would then be contracted — at suitably lucrative “outsourced” rates — to do the same work as when they were employed by the department. A variation of this outsourcing was for the former public employees to set themselves up as consultants, lucratively rewarded, of course.

All these and similar issues resurfaced — as though for the very first time — in 2020 with the Covid-19 pandemic. Dysfunctional municipalities and state departments were again greeted with the same shock, disbelief, alarm and anger as on all previous occasions. So, too, was the recognition that the problems were of a magnitude beyond any specific municipality, department or senior manager. Covid-19 made the need for systemic change widely acknowledged.

Anthony Turton, the water specialist perhaps best known for saying things others shy away from, was typically forthright in a recent article on the appalling state of our sewage system This systemic dysfunction, according to him, demonstrated the ANC’s prolonged “zero capacity to learn on the job and improve its performance”.

Zero capacity, in my view, is not the problem. Sufficient capacity exists within the ANC and its senior advisers. What they’ve been unable to do is move beyond the stranglehold of their 30-year-old political-economy shibboleths.

These can be summarised as austerity and privatisation, mainly in the form of public-private partnerships, and outsourcing based on a tender system to prop up the policy of promoting a black bourgeoisie.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Cholera — examining the horrific consequences of government’s own contaminated policy choices

The foundational nature of these policies, alongside the concurrent stranglehold of neoliberalism, explains why we constantly learn nothing from our repetitive crises, despite our ever-expanding knowledge. This will be the subject of the second part of this article. DM

Jeff Rudin works at the Alternative Information & Development Centre (AIDC).

The dearth of capacity is just another product for deployment; it has been, is and will forever be a disaster waiting to happen.