TRUTH AND JUSTICE OP-ED

Judicial independence and the rule of law in Eswatini – a true test of democracy in practice

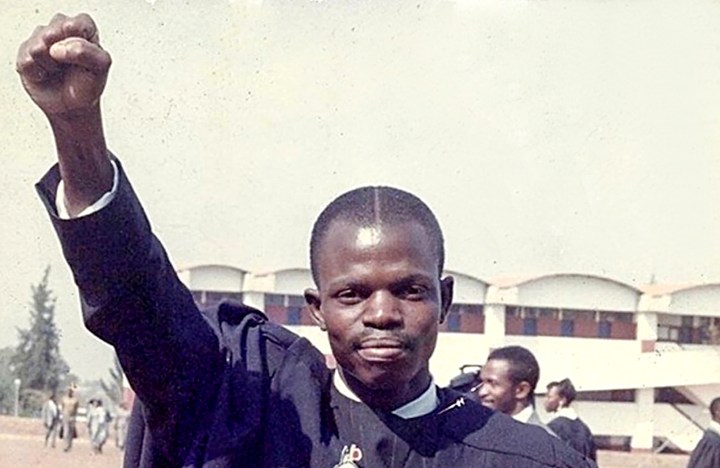

This is the keynote address at the inaugural memorial lecture at the Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, in honour of its alumnus, the leading Swazi human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko, who was murdered in January 2023. The event was held in collaboration with the University of eSwatini’s faculty of law, the Law Society of Eswatini and the Coordinating Assembly of Non-Governmental Organisations.

Tanele Maseko, sons Nkonsenhle and Nkosivile, and colleagues, thank you for joining us to celebrate courage. The University of Pretoria, my alma mater, thank you for hosting this historic, revolutionary event.

Thulani Maseko came from humble beginnings. When he met Tanele, his wife, he declared up front that he had a duty as the only surviving son, to build a house for his mother. He built a four-bedroom house which remains the family home. Although as an African man he had conventional ideas, to Tanele he was a partner. He consulted her on all matters.

In 2008 he was arrested under the Suppression of Terrorism Act because he exercised his freedom of expression to call for memorialising two activists who had been killed because they were perceived to be terrorists.

Upon his release he went on a scholarship to the United States of America to study. Two years later, he returned. Their son Nkonsenhle was born on 31 March 2011. Much to his delight, Thulani’s birthday was also in March.

After their second son, Nkosivile, was born in 2015, Thulani devoted himself to community work, to educating the public about the differences between elections and selections. In 2018 he was arrested and jailed for 18 months for contempt of court; he had penned an academic article criticising the erstwhile chief justice. Once again, he was punished unlawfully for exercising his right of freedom of expression. On appeal, his conviction was overturned. Simultaneously, threatening rhetoric from the authorities escalated.

His final hours

Fast forward to Saturday, 21 January 2023. As usual Tanele dropped off their sons at soccer. Unusually Thulani insisted on Tanele spending the day with him. She accompanied him to his law practice in the city. He attended to his accounts. They went out to lunch. About 4.30pm they drove back home. On the way back, Thulani held Tanele’s hand, and repeatedly expressed his gratitude to her for loving him and their children. On arriving home, he checked the mango trees. Together they called their sons to have dinner.

Kenyan human rights defenders at a candlelight vigil in Nairobi on 28 January 2023 in solidarity against the murder of Eswatini human rights defender Thulani Maseko. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Daniel Irungu)

Earlier that day the king had made a speech when he dispatched his regiment. After dinner, Thulani listened to the speech on his tablet. He consulted the constitution and remarked to Tanele that the speech was unconstitutional, and that “this man was vying for blood – [Thulani’s] blood”. The family was still together when Tanele noticed a shadow at the window. Through the lace curtains she saw a tall man carrying a gun. She was about to scream. She heard two shots. One struck Thulani in his head and the other in his heart. Instantly he was cold. His wife and two tender-aged children live with this horror forever etched in their hearts and minds.

When the police from the head office in Manzini eventually arrived, they retrieved the spent cartridges from the couch where Thulani had been seated. To date Tanele has not been informed of any progress with the investigation. At some point the police wanted to see his devices and even threatened to take her to court to get them. Courageously, Tanele held her ground; she refused to hand them over, reminding the police that Thulani was the victim, not the perpetrator of crime. What has happened to the ballistic tests on the cartridges retrieved from the couch is a question that screams out for an answer.

History relived

Thulani Maseko, a human rights lawyer, a truth seeker, was cut from the cloth of Griffiths and Victoria Mxenge. Their story holds lessons for all who care to heed them. The Mxenges practised law two streets away from my office in the 1980s. They represented activists in many political cases in KwaZulu-Natal. Agents of the apartheid government’s death squads butchered Griffiths with 45 stab wounds on 19 November 1981. His wife Victoria, mother of their three young children, took over their human rights law practice.

See Ranjith Kally’s Memory against forgetting a for a photograph of the pallbearers Pius Langa and Yunus Mahomed at the funeral of Griffiths Mxenge.

In the Eastern Cape, the Cradock Four – Fort Calata, Matthew Goniwe, Sicelo Mhlauli and Sparrow Mkhonto – were assassinated. Apartheid South Africa denied responsibility for abducting, assaulting and burning them to death in June 1985. However, on 22 May 1992, the New Nation newspaper exposed Colonel Harold Snyman’s top-secret military message calling for their “permanent removal from society”. In December 1999, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission denied amnesty to Colonel Snyman and five other security branch officers.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Leaders from across the world gather to remember peaceful human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko

Addressing the 50-000-strong crowd at the funeral of the Cradock Four, Victoria Mxenge condemned the assassinations as desperate acts of cowardice. Two weeks later, Victoria too fell victim to apartheid’s death squads.

On 1 August 1985, four men gunned and axed her to death in the driveway of her home, in front of her children. In 1987, a Durban magistrate refused to order a formal inquest into her killing, ruling that she had died of head injuries and had been murdered by persons unknown. Agents of the apartheid government’s death squads – Dirk Coetzee, Almond Nofomela, Joe Mamasela, Brian Ngqulunga and David Tshikalanga – confessed to killing Griffiths Mxenge. In 1996, the amnesty committee of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission granted them amnesty. Bongi Malinga confessed to shooting Victoria Mxenge five times before axing her, but no amnesty was applied for or granted in his case.

Treason trial

The day after her assassination, the treason trial of 16 leaders of the UDF and the ANC was scheduled to start. The law firm of Mxenge and our practice, Yunus Mahomed and Associates, were part of the defence team.

When the trial in Pietermaritzburg eventually started, much of the evidence against the accused in that case took the form of tape recordings of speeches that the accused made to mobilise and conscientise the public, to organise them to act peacefully in the struggle against apartheid.

The trial began with an objection to the admissibility of the recordings. The state adduced evidence through a witness who claimed to be an expert in politics, which allegedly qualified him to link the speeches to the political unrest sweeping the country. Ismail Mahomed, who later became Chief Justice, led the defence team. The judge presiding was Judge President John Milne. After hearing the evidence and the argument, Judge President Milne delivered a seminal judgment that, to date, remains authoritative on the admissibility into evidence of videotape recordings. In S v Ramgobin and Others 1986 (4) SA 117, Milne JP held that it must be proved that the exhibits are original recordings and that there exists no reasonable possibility of interference with the recordings. His judgment led to all the accused being discharged from prosecution, without having to testify.

Judges with conscience and imagination, conscientious and clever judges will strive to find appropriate rules of law to apply to circumstances of a case to achieve justice.

After the trial and when the recurring states of emergency continued to fill prisons with anti-apartheid activists, Yunus Mahomed and I sought a meeting with Judge President Milne to discuss the prison conditions of detainees held without trial and access to family and lawyers. After that meeting, Judge President Milne directed that political detainees held under emergency laws should have access to lawyers and family visits. That practice of judges visiting prisons continues to date, a position currently filled by retired Justice Cameron.

A few years later we encountered John Milne as an appeal judge in the Appellate Division in Bloemfontein. ANC activist Sunny Singh had returned from exile in 1991. He was applying for a passport at the Department of Foreign Affairs, which was across the road from our law practice. An official alerted the police that there was a terrorist in town. Sunny was arrested. A judge granted an order for his urgent release. The state took the order on appeal. The ground of appeal was that the arrest was lawful because Sunny had committed the crime of having a passport with a false name. In the Appellate Division, unimpressed by the case for the State, Judge Milne invited the advocates to his chambers. He asked the advocate for the state the following question: Is a rose by any other name not a rose? That was the end of the appeal. Sunny Singh subsequently succeeded in a damages claim for unlawful arrest and detention.

As I prepared for this lecture, Yusuf Vawda, a human rights attorney and an academic who retired from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, reminded me of the role Judge President Milne played during Yusuf’s detention incommunicado under security laws in 1987. An application had been brought for Yusuf’s release. Judge Kriek sat with the case without delivering a judgment. After three months of waiting, Yusuf wrote to Judge President Milne to seek his intervention. Nothing happened for a while. One day, Yusuf was taken from his cell to the visiting room. There he found Judge Brian Galgut. Judge President Milne had sent him to check on Yusuf! For the detainees, the visit revitalised hope for a democratic, nonracial South Africa grounded in the rule of law, enforced by trustworthy, independent and impartial judiciary.

Lessons from history

So, what lessons do we learn from this brief account of history?

First: Judges with conscience and imagination, conscientious and clever judges will strive to find appropriate rules of law to apply to circumstances of a case to achieve justice. Judge Milne had been appointed by an apartheid president. However, as a legal scholar, law meant justice to him. By applying a technical rule of law on evidence, he directly raised the standard of proof prosecutors must produce before the burden shifts to the accused to defend themselves; indirectly, he gave effect to the right to freedom of expression in politics.

Irrespective of one’s personal preference for a system of governance, be it monarchism, liberal or social democracy, or communism, we Swazis signed up for liberal democracy. We must make it work.

Judges like John Milne are respected, remembered and loved. Good judges turn the tide of strife towards democracy. Judges who are not respected are those who prowl the corridors of power, puffing up like bullfrogs whenever they are addressed as “excellencies”, who euphemistically accept bribes as loans and gifts, who are biased, and who have no clue about human rights and the rule of law. They will go down in history as accomplices, if not perpetrators of human rights violations. They will not be forgotten.

Second: Political killings occur when the killers run out of ideas and the courage to dialogue with their opponents, when they know that they would lose in defending their unjust causes, when they have their backs to the wall and, most of all, when they are afraid. Like wounded animals in fear, they strike out more viciously than before.

Third: Political killings are not acts of courage but of cowardice. What the cowards do not realise is that as assassins they will be caught and exposed. If their troubled consciences do not cause them to confess voluntarily, then their cowardly accomplices will betray them. Assassins have no place to hide. International if not national courts, and truth and reconciliation commissions will excavate the truth.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Lawyers live in fear as Swazi state intensifies crackdown on activists

Fourth: Assassins create martyrs. An annual lecture at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and Nelson Mandela University continue to honour the Mxenges’ commitment to the struggle for democracy in South Africa. Streets, buildings and an advocates group are named after them. In 2006, Mlungisi Griffiths Mxenge and Victoria Nonyamezelo Mxenge were awarded the Order of Luthuli in silver for “their excellent contribution to the field of law and sacrifices made in the fight against apartheid oppression in South Africa”. Similarly, the Thulani Maseko Lecture is a formative step in memorialising a hero in the struggle for human rights, development and democracy.

Fifth: The struggle for democracy follows a pattern of peaceful contestation, violent reactions, assassinations, peace talks, settlement, truth, reconciliation, amnesty and prosecution of unrepentant assassins. Violence must end at some point. The sooner the protagonists get to settlement, the fewer the hardships will be, conducing to a greater readiness to reconcile. Both world wars ended in armistice and peace treaties. The Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union. How and when will the contestation between pro- and anti-democrats in Swaziland end? End it must.

Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko’s wife Tanele spoke at his memorial about the pain she has endured as a result of her husband’s passing. When Maseko was imprisoned in 2014/15 Tanele had travelled around the world calling for his release. (Photo: Leon Sadiki)

Let’s simulate

Like Victoria Mxenge, Thulani Maseko was also busy with a treason trial when he was gunned down. What I’m about to do is not to lecture you. Henceforth, I intend to involve you in a simulation. You shall be the judges in the court of public opinion. I will address you as Thulani Maseko might have addressed the court on behalf of his clients MP Bacede Mabuza and Mthandeni Dube. You will be delighted to know that you have all the legal materials before you to make your judgment, thanks to the learned Judge Mumcy Dlamini. She quoted at length the recordings of the speeches that my clients made. They form the basis of the main count one of terrorism and counts two and three of murder. I assume that her transcription is correct – you will appreciate that I have not been able to consult my clients about this aspect. Whereas my clients’ public addresses reached a few hundred people, the transcription is now available worldwide through the publication of the judgment online.

Judging the case for democracy

Justices of the court of public opinion, I begin my address by identifying the core elements of democracy. That will help you to assess the state of democracy in the Kingdom of Swaziland. Without such assessment, adjudicating the case on the facts for my clients would be incomplete. My clients Mabuza and Dube were convicted on 1 June 2023. With the utmost respect, I submit that their arrests, detention and now conviction are unconstitutional and unlawful. I seek their acquittal on all charges.

Core elements of liberal democracy

Constitutionalism is a paradox. Democracy defined by Abraham Lincoln as government of the people, by the people and for the people, is grounded in majoritarianism. Constitutions seek to limit the excesses of majoritarianism. That is a tension ever evolving and, like natural selection, transforming society hopefully to higher levels of organisation and wellness.

Minimally, liberal democracy embodies the virtues of many freedoms, the rule of law, an independent judiciary, elections, a vibrant opposition, accountability and transparency. Other hallmarks include human rights such as the rights to equality, dignity and personal security. Many speakers at the landmark conference of the Association of World Election Bodies in October 2022 in Cape Town, South Africa, identified the essence of liberal democracy to be good governance, functioning legal and political institutions for enforcement to combat corruption, service delivery and development.

Winston Churchill said on 14 November 1947:

“Many forms of government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time”

Holding elections is no guarantee that bigots and despots would not govern. In contrast, some one-party states are known to promote the best interests of the majority of the population. One of the reasons for liberal democracy morphing into democratic recession worldwide, is because governors violate the human and livelihood rights of those whom they govern. Irrespective of one’s personal preference for a system of governance, be it monarchism, liberal or social democracy, or communism, we Swazis signed up for liberal democracy. We must make it work.

Democracy Swazi style

It would be a colossal mistake to assume that no system of peaceful governance before constitutional democracy descended on Swaziland. Some sympathy is extended to drafters whose mandate is to parachute liberal democracy over traditional systems. It falls beyond the scope of my clients’ case to undertake a detailed exposition of the contradictions between the Constitution of the Kingdom of Swaziland dated 26 July 2005 and the traditional system that prevailed for centuries before. For now, let it suffice to note, for instance, that even though the constitution is the supreme law of Swaziland (section 2(1)), and that any other law inconsistent with it is void, the monarchy derives rights, prerogatives and obligations from the constitution or any other law, including Swazi law and custom (section 4(4)). So, is the constitution, Swazi law or customary law the supreme law? Another contradiction arises from the absence of Montesquieu’s fundamental tenet of liberal democracy, namely, the separation of powers principle. Under Swazi law there is no such separation. The king prevails over the judiciary, executive and legislative branches of government.

A process that does not involve the nomination of candidates seeking political office, campaigning and competition, cannot be elections but selections.

Ironically, learned Judge Mumcy Dlamini, in convicting my clients, cites copious extracts from judgments of two erstwhile chief justices of India – Dipak Misra and Natwarlal H Bhagwati – on the supremacy of the constitution (para 46-47). In the largest democracy in the world, both the supremacy of India’s constitution and its grounding in the separation of powers principle are well established. That is not so in Swaziland.

Elections

Governance in Swaziland is grounded in a traditional system of chieftaincy led by the monarchy. Section 79 of its constitution asserts that Swaziland is a democratic participatory, tinkhundla-based system which emphasises devolution of state power from central government to tinkhundla or local authority areas. Individual merit as a basis for election or appointment to public office. Administratively, Swaziland is divided into four regions, 55 tinkhundla centres or administrative divisions, and 360 chiefdoms. Each inkhundla (singular of tinkhundla) falls under the authority of an executive committee called Bucopho. Members of Bucopho are elected from the chiefdoms or polling divisions within an inkhundla. Members of the Elections and Boundaries Commission, all of whom are appointed by the king on the advice of the Judicial Service Commission, oversee the elections at primary, secondary or other level. (section 90 (7) (a))

However, elections are not conducted as a competition for public office. Campaigning is not allowed. Neither are political parties recognised as participants in the electoral process. The right to freedom of expression entitles people to promote their preferred candidates in a competitive election to serve in government. Having a vibrant opposition that challenges the governors to improve the quality of their decisions, can only be in the best interests of the governed. A process that does not involve the nomination of candidates seeking political office, campaigning and competition, cannot be elections but selections. This is the point that my clients sought to share with their audiences and for which they were arrested and now convicted. Holding regular free, fair and inclusive elections is the competitive process for establishing democratic representative and accountable governments.

Freedoms – rights and protections

For liberal democracy to succeed all the core requirements must function efficiently and interdependently. Take the rights to many freedoms. The constitution of Swaziland provides in section 14(1) the fundamental human rights and freedoms of individuals, and guarantees specifically the right to freedom of conscience, of expression and of peaceful assembly and association, and of movement. Considering that these freedoms are repeated as protections at sections 23, 24 and 25, Swazis, in general and my clients in particular, should have been able to rely on them when they called for an elected and not an appointed prime minister and encouraged people to deliver petitions in support of this call. Instead, they have been unconstitutionally arrested, charged and convicted for exercising their constitutional freedoms.

Freedom of expression includes the right to debate different forms of governance within and outside of parliament. If no agreement is reached, contenders should be free to approach an independent, impartial court to determine the disputes. In South Africa, a new party aggrieved by the electoral laws approached the Constitutional Court. That resulted in an amendment of the law on Monday, 19 June 2023 to provide for independent candidates to stand in the elections in 2024.

Rule of law

As for the rule of law, it has both a metaphysical as well as a political notion. We are concerned with the rule of law at its most basic to mean that no person is above the law. Law rules, not individuals. Frank Michelman defines the political notion of the rule of law as the formula that “names a category of preferred or desired governmental practices, comprising elements of authority and obligation, transparency and accountability, regularity and fairness in the extension and administration of state power.” (Frank Michelman, Constitutional Essentials on the Constitutional Theory of Political Liberalism (p 173))

Grounded in the idea of truth, the rule of law principle requires legislators to make rules in the interests of good governance. What if the law to be applied is bad for governance, the population and democracy, because it favours particular individuals and classes, or because it does not allow democracy to flourish as political parties are not allowed to offer candidates to stand for elections, to be elected into government and to govern? In a functioning democracy, it should be permissible to test the validity of rules of law before an independent impartial judiciary.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Thulani Maseko’s murder exposes the political wrangling hobbling Eswatini’s march to democracy

Section 245 of the constitution of Swaziland prescribes the procedure for effecting amendments to the constitution. Section 246 permits amendments even to specially entrenched provisions, including those relating to the kingdom, its constitution and the monarchy.

Determining whether the process for effecting amendments is fair, considering the dominance in the parliament by appointees of the king, and that any amendment requires the king’s assent under section 245 (5), go to determining whether in substance, if not in form, Eswatini is a genuine democracy.

In this case, my clients are charged for encouraging people to reject the appointment of the prime minister. Because he is not elected, they contend that he conducts himself without accountability to those whom he is appointed to represent. The question is whether the law permitted my clients to call for amendments to the constitution by following due process so that prime ministers can be elected, not appointed. The answer must be a resounding yes.

Portrait of a kind, humble and peaceful man: At his memorial, Thulani Maseko’s fellow activists told of how he was always concerned with others’ security, but never his own. He would joke darkly ‘if they come for me they will find me in my home’. (Photo: Leon Sadiki)

Judicial independence

In Eswatini, as in South Africa, the Judicial Service Commission oversees the process of interviewing and selecting judges for appointment by the head of state, be it the king or the president. However, it is a rule of law that judges must be independent, impartial and persons of integrity. The Bangalore principles prescribe these qualities as imperative for an independent judiciary.

The Times of Swaziland dated 17 October 2021 reported that Judge Ticheme Dlamini, who had recused himself from a commercial case, was instructed by the chief justice to continue to hear the matter. I wonder whether the litigants in that case were satisfied that justice had been done by being served by a judge unwilling to hear their case.

However, it is not often that one finds evidence of interference in judicial discretion in a judgment. The Swaziland News of 15 September 2021 quoted from the judgment of learned Judge Mumcy Dlamini in the bail application for my clients: “In the result, there is no need for this court to make a determination whether there are new grounds for the present bail application. I find that this court is [functus] officio. Applicants’ remedy, if any, lies not with this court but elsewhere in this regard.” Her statement is ambiguous. She could have been referring to an appeal to a higher court. However, a reference to undue influence cannot be excluded in the context of the newspaper’s exposé that the king had ordered the police to arrest my clients. Furthermore, a week earlier The Swaziland News had reported that she feared for her life and was seeking asylum in the UK.

However, it is the judgment convicting my clients that suggests that there might be undue influence. Like the UDF treason trial before Judge President Milne, the gist of the Crown’s case is recordings of speeches that my clients made calling for elections and encouraging people to file petitions to that end. In an unsustainable leap of logic, the learned Judge Mumcy Dlamini allegedly found that those speeches resulted in death, injury, damage to property, endangerment of peoples’ lives and disruption of services during June 2021. Most startling are the counts on which my clients have been found guilty. They were found guilty on count one and the first and second alternatives to count one. The order is startling because when a finding of guilty is made on the main count, the alternative counts fall away. Such an order is, with the greatest respect, not the work of anyone qualified to practise law. Although the electronic copy of the judgment I have bears a signature, I humbly request the justices of the court of public opinion to find that Judge Mumcy Dlamini, formerly the director of public prosecutions, and a high court judge with more than 10 years’ experience, did not make the decision to issue that order. For if you were to find that she did issue that order, then you must also find that she is unfit to be a judge.

In conclusion, contrived prosecutions of political opponents are symptomatic of democracy in recession. If such prosecutions result in convictions and deprivation of freedoms, merely to annihilate opposition and cling to power, Swazis will not be at peace. Like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission excavated assassins, and the Zondo Commission excavated corruption, the truth will prevail.

I have been silenced from representing my clients in the courts of Eswatini. I turn to you judges of the court of public opinion. You want peace and prosperity for all people. You value democracy, human rights and the rule of law. You are independent and impartial. You will act with integrity. Accordingly, I humbly ask that my clients be found not guilty, be acquitted of all charges and released from prison forthwith.

Thank you. DM

Dhaya Pillay is a retired judge, writing in her personal capacity.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.