LANGUAGE LANDSCAPE OP-ED

Why are learners reading worse in African languages? A response from the Department of Basic Education

The Covid-19 pandemic was a temporary shock to the education of a generation of children. It was not reflective of a general decline in the functioning of the school system, so there is no reason South Africa should not return to its pre-pandemic trend of improvement.

The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (Pirls) 2021 results were released last Tuesday. Of the 32 countries with comparable trend data between 2016 and 2021, a decline in reading outcomes was seen in 21 countries. South Africa, unfortunately, was among these. The results show that 81% of our Grade 4 learners cannot read for meaning, worse than the 78% in 2016.

The decline is extremely unfortunate, but it was not surprising because school closure was one of the early responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. In South Africa, this led to the loss of about 60% of the academic year in 2020 and 50% in 2021. This means the learners who participated in Pirls in 2021 were still experiencing the final stages of a nearly two-year educational disruption.

Much has been written by education commentators, academics and the media on the results, the contributing factors and what should happen in response.

Our learners wrote in all 11 official languages and I focus on making sense of the vast difference in performance by language.

Read more in Daily Maverick: From bad to worse: New study shows 81% of Grade 4 pupils in SA can’t read in any language

Read more in Daily Maverick: A proposal to upskill the 81% of Grade 4 children in South Africa who can’t read

The language landscape and performance in South Africa

About 70% of learners in South Africa are in no-fee schools that use an African language as the language of instruction for the first three grades. During this time, most children learn English as a subject and then experience a switch in Grade 4 when English becomes the language of instruction and their African languages become a subject.

In contrast, about 9% of learners start school in Afrikaans and do not switch at any stage but continue with Afrikaans after Grade 4 until matric. Similarly, the 23% that start in English continue past Grade 4 without any language switching, also until matric. Aside from the advantage of not having to change languages, schools that start and continue in English and Afrikaans are generally wealthier, fee-paying schools. They also had the least disruptions during the pandemic, losing far fewer days and less learning.

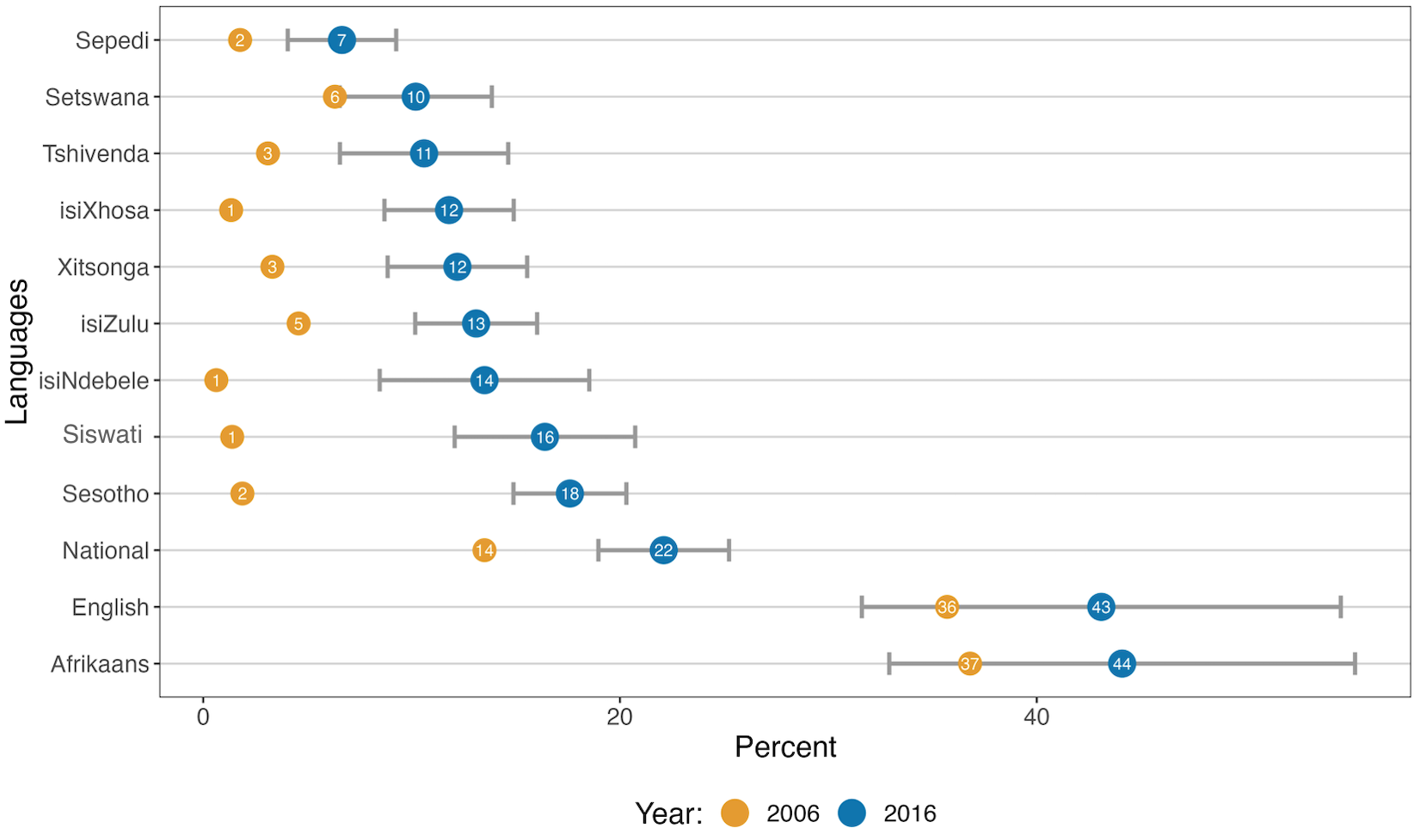

So, a second unsurprising aspect of the Pirls 2021 results is that the highest-performing languages were English and Afrikaans. Both of these languages maintained their 2016 levels. They are the only languages in South Africa that did not decline. Unfortunately, all the African languages declined, the worst being Sepedi and Setswana.

The distinction between English and Afrikaans on the one hand and the African languages on the other is long-standing. We saw this in Pirls from as early as 2006 when we first participated. But we then saw substantial gains among African languages before the Covid-19 shock and disruptions.

There were larger improvements in African languages than in English and Afrikaans. These gains exceeded 70 points, with the largest of these among the Nguni languages. Of course, this is an improvement from a much lower base than English or Afrikaans but the gains could be quantified as more than two years of schooling.

These gains in African language reading and literacy, achieved within no-fee schools serving our most rural and vulnerable communities, were among the largest improvements seen around the world in assessments like Pirls.

This is not something to scoff at.

So, while the current results are disappointing and much more planning, financing, support and tracking is needed, we should not dismiss the previous improvements that were made, nor the lessons they offer for improving in the future.

What does this mean for African languages?

It would be a mistake to blame the African languages for the decline. These results do not mean that all children should start school in English and Afrikaans; it remains the right decision to start school in the language you know best — for most it’s an African language. Our African languages are a strategic resource and not a hindrance to learning to read. Local and international research on this is clear.

So, what does all of this mean? We should be careful how we understand the overall education Covid-19 shocks experienced by poorer schools compared to wealthier schools. And it would be a bigger shame to fail to recognise the improved capability of the system to deliver better education for the majority because of the Covid-19 shock.

Percentage of South African Grade 4 learners reaching the Low International Benchmark in 2006 and 2016 by language

Source: Mohohlwane, Mtsatse, Courtney. 2023 (forthcoming). In Tracking changes in reading literacy achievement over time: A developing context perspective.

How can we support African languages?

While we recognise that reading for meaning — what Pirls measures — is the ultimate goal of reading, reading is a complex and hierarchical process. A range of foundational reading subskills need to be mastered before a learner can understand a text. To support these early subskills the department has led a collaboration with linguists, data analysts and education experts to develop key benchmarks of early reading outcomes. Oral fluency reading benchmarks for letters, words and passage reading are necessary for children to reach in grades 1, 2 and 3 to be on track to read with adequate comprehension in Grade 4.

Given the different orthographic structures of African languages, these benchmarks were developed separately for the different language groups.

Before 2019, none of this kind of work existed for our local languages and, today, 10 out of the 11 languages have reading benchmarks. All languages will be completed by the end of the year. The next steps are to systematically incorporate the reading benchmarks into the curriculum, strengthening teacher training and system monitoring nationally and provincially. It would also help if ordinary South Africans used these in their homes, interventions and NGOs.

Will South Africa do better next time?

The Covid-19 pandemic was a temporary shock to the education of a generation of children. It was not reflective of a general decline in the functioning of the school system, so there is no reason South Africa should not return to its pre-pandemic trend of improvement.

In fact, we could see exceptionally large improvements in the next five to 10 years if we invest heavily in Home Language Literacy by providing the right reading materials developed in each African language, training teachers how to teach reading in those languages, and monitoring progress in those foundational skills which build towards the outcome of reading with meaning. DM

Nompumelelo Mohohlwane is a researcher in the national Department of Basic Education.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A very interesting article which highlights some comments made at a function I attended last night for KILT (Knysna Initiative for Learning and Teaching).

Their huge success, even through covid, has changed so many young lives and this remarkable NGO started by Gill Marcus and some educators in 2017 operates on education in the whole. Home language tuition is a noble cause, but for anything to succeed and thrive it must be in a whole supporting environment. Education is most successful when the Maslow hierarchy of needs is taken into account as it creates for wholistic support. Food, love and family support are prior requirements to educational success. KILT is a working successful model worth reading about for people doing this type of building.

we were 78% before covid so let’s not blame it being 81% now on covid and rather focus on the very concerning fact our system fails 4 out of 5 youngsters.

Is there a similar test at Grade 7 or 8 and what do those results show? I’m pretty sure there was a test our kids did that measured not just reading for understanding, but math literacy as well.