TRAGEDY REVISITED

Looking back on Life Esidimeni – ‘Mental health still comes last in healthcare’

The 2016 Life Esidimeni tragedy was a watershed moment for mental healthcare. It should also have been a wake-up call. Why this hasn’t been the case is sober realisation that what comes next may look a lot like what came before.

Seven years after the Life Esidimeni tragedy, Tracy sometimes still hears the cries of the dead – the mental health patients who became victims of bad government decision-making which turned into a horror story.

She wishes others heard the cries too.

“No one listens to patients, no one asks them what they want – not even now,” says the occupational therapist (OT), who has worked in the Gauteng public health sector for more than 20 years. She hides her identity for publication because a deepening culture of intimidation keeps government employees like her silent.

After 20 years she has her own timeline; personal witness to mental healthcare failings deepening into dysfunction. The chronology blips at the point of 2016 – the year the Life Esidimeni tragedy became headline news. In 2015, the Gauteng department of health (GDoH) decided to end its contract of nearly 30 years with private mental healthcare service provider Life Esidimeni, ostensibly as a cost-cutting measure. Its decision meant about 1,500 mental health patients were placed into 27 alternative facilities. The resulting neglect, starvation, abuse and inferior care of patients would be exposed as what led to the now known deaths of 144 people.

Subsequent investigations followed and resulted in the Health Ombud’s report of 2016. The report found that all 27 NGO facilities were unlicensed, that the cost-cutting rationale undermined patients’ rights to mental healthcare and that there was prima facie evidence that “certain officials and certain NGOs and some activities within this department led by the then health MEC Qedani Mahlangu violated the Constitution” and contravened the National Health Act and the Mental Health Care Act. An arbitration process between the government and the families of the Life Esidimeni deceased followed and a judicial inquest is currently under way.

For Tracy the Life Esidimeni tragedy is a haunted moment in her life. She remembers in the aftermath standing in a converted horse stable with no windows to look out of, that that was exposed as one of the facilities the GDoH approved as fit for care for about 12 patients.

“It was a place owned by a private person who was approved to take care of 12 patients. I just stood in those stables and cried with the patients when we went back there – there was nothing else to do,” she says.

There are still only 16 beds per 100,000 people available for acute mental health admissions.

The ghosts of 2016 stay with her. It’s because she says the deaths should have shaken and shamed authorities to take responsibility and to commit to action and change.

“Things are not much better now because mental health still comes last in healthcare – we are always told there are not enough resources. Sometimes I go to work and all I can do for the patient in front of me is to listen to them, to respect that someone with a mental health condition also has dreams and wants to have purpose in their lives,” she says.

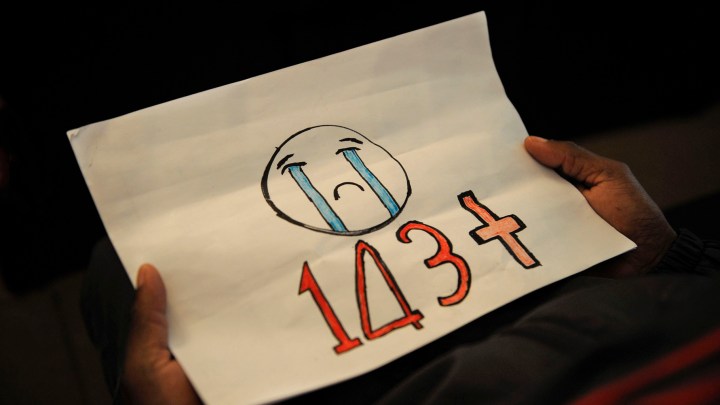

Protesters during the testimony of former Gauteng health MEC Qedani Mahlangu at the Life Esidimeni arbitration hearings on 22 January 2018 in Johannesburg. (Photo: Gallo Images / Alet Pretorius)

Tracy sees about 90 patients a month. It’s more than double what’s recommended in the hospital where she works in Gauteng. OTs in mental health play an essential role to help patients function optimally in their day-to-day activities. It can be skills to cook for themselves, to manage finances, recognise triggers and to have routines to stick to their medication regimes.

A revolving door of care

“The number of people who have mental illness is far more than what we can handle. The system is overloaded and we are always playing catch-up, even as the backlog keeps growing,” she says.

She says not enough posts are being created and simultaneously vacancies remain unfilled. Admission protocols at her facility also only allow male patients a maximum of a 12-day stay. For women it’s up to 20 days. Both are truncated hospital stays.

“Hopelessly short,” she says.

“As soon as the patient is medicated and can speak nicely to you then we let them go even though we really need 30 days to assess if they are coping. It means that they become part of a revolving door of care – after a few weeks of being discharged we end up seeing that same person again needing institutionalisation.

Tracy, like all mental healthcare workers, currently works with no National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan in place. The last framework and strategic plan was for 2013 to 2020. It’s now three years overdue for approval and implementation – even with the spectre of Life Esidimeni hanging over the national and provincial departments of health.

Family members of patients at the 2018 Life Esidimeni arbitration in Johannesburg. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

Mental health review boards that are supposed to have a watchdog function protecting patients’ rights have been non-functioning for years, according to patient rights groups.

A decade ago already the policy framework of that time acknowledged that “mental health continues to be underfunded and underresourced… despite neuropsychiatric disorders ranked third in their contribution to the burden of disease in South Africa”.

The government document also raised and recognised challenges such as the lack of “accurate routinely collected data regarding mental health service provision and huge disparities in how different provinces addressed mental healthcare needs and allocated spending”.

A decade on, the same challenges continue. Disaggregated data to establish expenditure on mental health from general healthcare budgets is lacking – as the authors of the 2019 report An Evaluation of the Health System costs of Mental Health Services and Programmes in South Africa found.

“The South African government does not track or specify dedicated budgets for mental health services provided through lower levels of care… We do not know how much is currently being spent, making estimates of the additional resources required for a viable mental health service difficult to estimate. This is particularly important when future efforts are to be focused on decentralising care away from the specialised care level to district, primary and community levels,” report authors Sumaiyah Docrat, Donela Besada and Crick Lund found.

Without the national strategy framework for mental health in place… mental healthcare staff simply don’t know what they’re supposed to do.

They also called it “alarming” that there was a treatment gap of 92%, meaning “fewer than one in 10 people living with a mental health condition in South Africa receive the care they need”. In 2019, the estimates were that 5% of the total health budget was spent on mental health service, which is lower than international benchmarks, they reported.

Currently, the 2023/24 total health budget for Gauteng is R5-billion of an overall budget of R158.9-billion. The estimate is that up to 4% of the population is in need of psychiatric support.

A woman is comforted during the Life Esidimeni arbitration hearing on 16 October 2017 in Johannesburg. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sowetan / Alon Skuy)

How did mental health become so grim?

How management of mental health became so grim requires a pull-back of the chronology to the mid-1990s.

A new democratic government looked to deinstutionalise in favour of channelling patients into a community-based framework of care. This was in line with World Health Organization guidelines as a positive shift to more dignified and integrated care for people with mental illness. It was a good move – on paper at least.

Professor Lesley Robertson, a psychiatrist working in the Sedibeng District health service and who was part of the expert panel for the investigations by the Health Ombud in 2016, says: “Life Esidimeni came about as a culmination of several decades of a national policy to deinstitutionalise but the process proceeded at a rapid rate across the country without any increase in community-based services.”

Robertson says as the Gauteng health department shifted to close long-stay institutions that at the time also included “halfway houses” as step-down facilities, the mandate was for “funding to follow the patient into districts and communities”.

The plan was to provide multidisciplinary specialist teams operating in a primary healthcare setting along with NGO residential and daycare centres being established. A partnership with the Department of Psychiatry at Wits University was also shored up for the expansion of community-based services at the time.

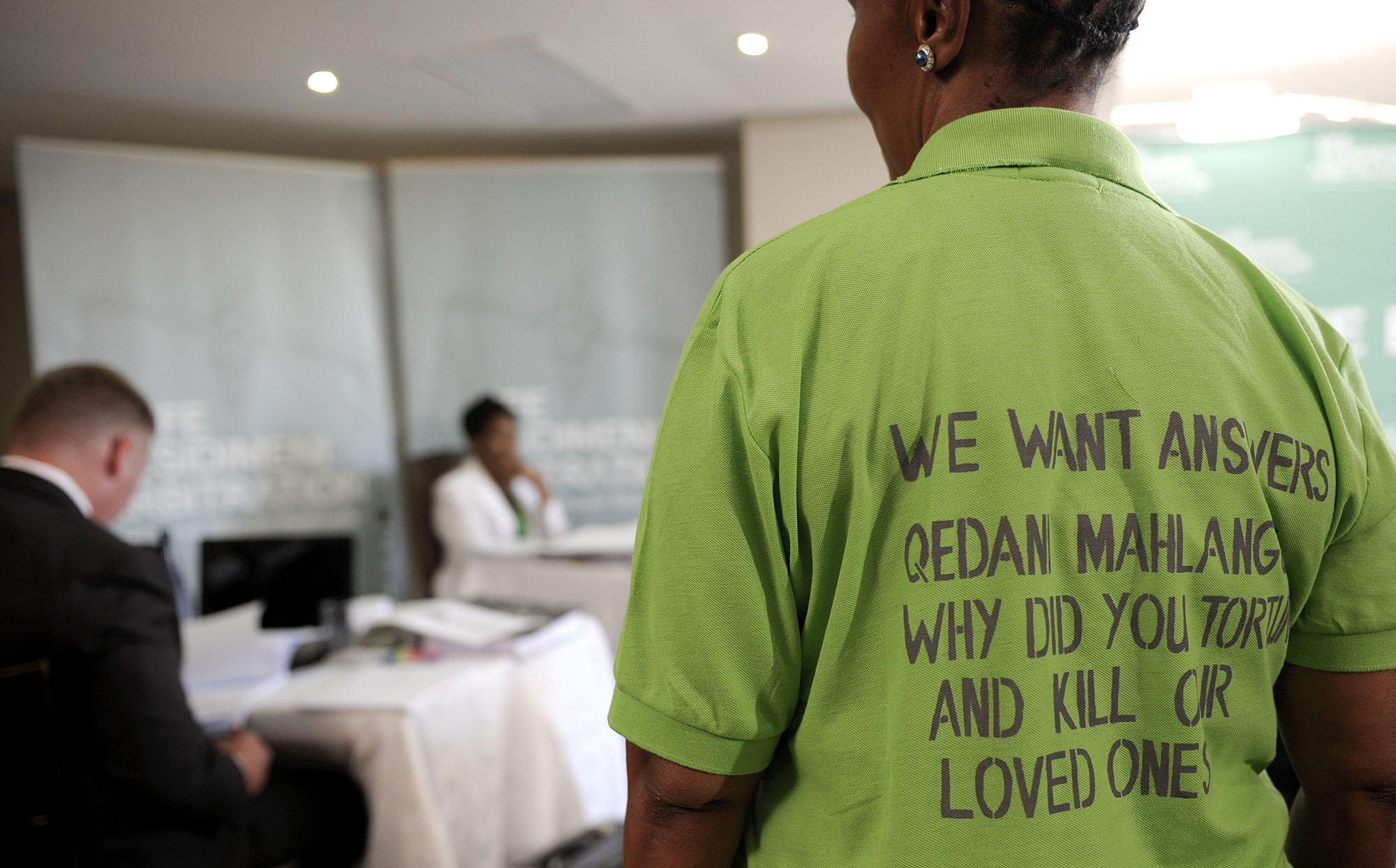

Qedani Mahlangu, former Gauteng MEC for health. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

But over the next 20 years “human resource allocation was not sustained”. Without a strong community-based network the programme failed, people fell through the cracks – they still do, or are simply stuck in a doomed cycle of inferior care.

There are still only 16 beds per 100,000 people available for acute mental health admissions. It is a significant shortfall considering that Robertson says just under a quarter of inpatient psychiatric expenditure is now being spent on readmissions within three months of a patient being discharged.

“The community-based care model has not made people more functional and able to participate in society,” she says. As people are considered “society misfits” they can become increasingly isolated, neglected and stigmatised by family, friends and also by law enforcement and clinic staff. They are also more affected by poverty – when they can’t access mental health services, they aren’t ever professionally assessed and don’t have paperwork needed to apply for disability grants.

She adds: “We’re making it harder for people to access care; it’s the basics of patients having to walk longer distances or travel further to get to a clinic where there are services. Then people face increased stressors like high unemployment, high levels of violence and trauma and increased risk [of] substance dependency.”

She says in the communities she works in, illegal drugs circulate freely and people with underlying mental health conditions are more susceptible to developing dependency problems.

Family member Wilhemina Thejane at the Life Esidimeni hearings in Johannesburg. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

Robertson says that without the national strategy framework for mental health in place there is no clinical programme guideline. Mental healthcare staff simply “don’t know what they’re supposed to do”. It means less accountability and less cohesion in planning for patient care.

Added to this, resource constraints are becoming a mental health burden for healthcare workers themselves.

She says: “You feel it on the ground as a lack of development of infrastructure year in year out. You also can’t say precisely what the reasons are for the situation – whether it’s corruption or not. And without knowing there are no investigations and no consequences, there’s growing despondency. It becomes harder to keep hopeful and healthcare workers can feel thwarted in their efforts to help patients.”

Costs of care

Eric Buch was deputy director-general of health in the GDoH in 1995. He says that by the mid-1990s the costs of the Life Esidimeni contract were already under “major scrutiny” in the province. But the department decided then to keep the contract going, knowing that community structures to support deinstitutionalising were not in place.

“Other providers with comparable offers were also not significantly cheaper,” he says.

Buch left the government in 1999 and is now chief executive of the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa (CMSA) and a professor in health policy and management at the University of Pretoria. He says there has been a slide since the 2000s worsening to the decision-making in 2015 by Mahlangu’s administration to go ahead with their Gauteng Mental Health Marathon Project that led to the Life Esidimeni disaster.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Marathon Project: Patient numbers exceeded NGO admission capacity, former health official testifies

Buch acknowledges that decisions made in the early days of democracy were coming off a low base given the priority to deracialise healthcare.

“You could make quite dramatic challenges without doing much because there just weren’t decent services for the majority of South Africans before democracy.”

Family member Maria Phehla testifies at the Life Esidimeni hearings. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

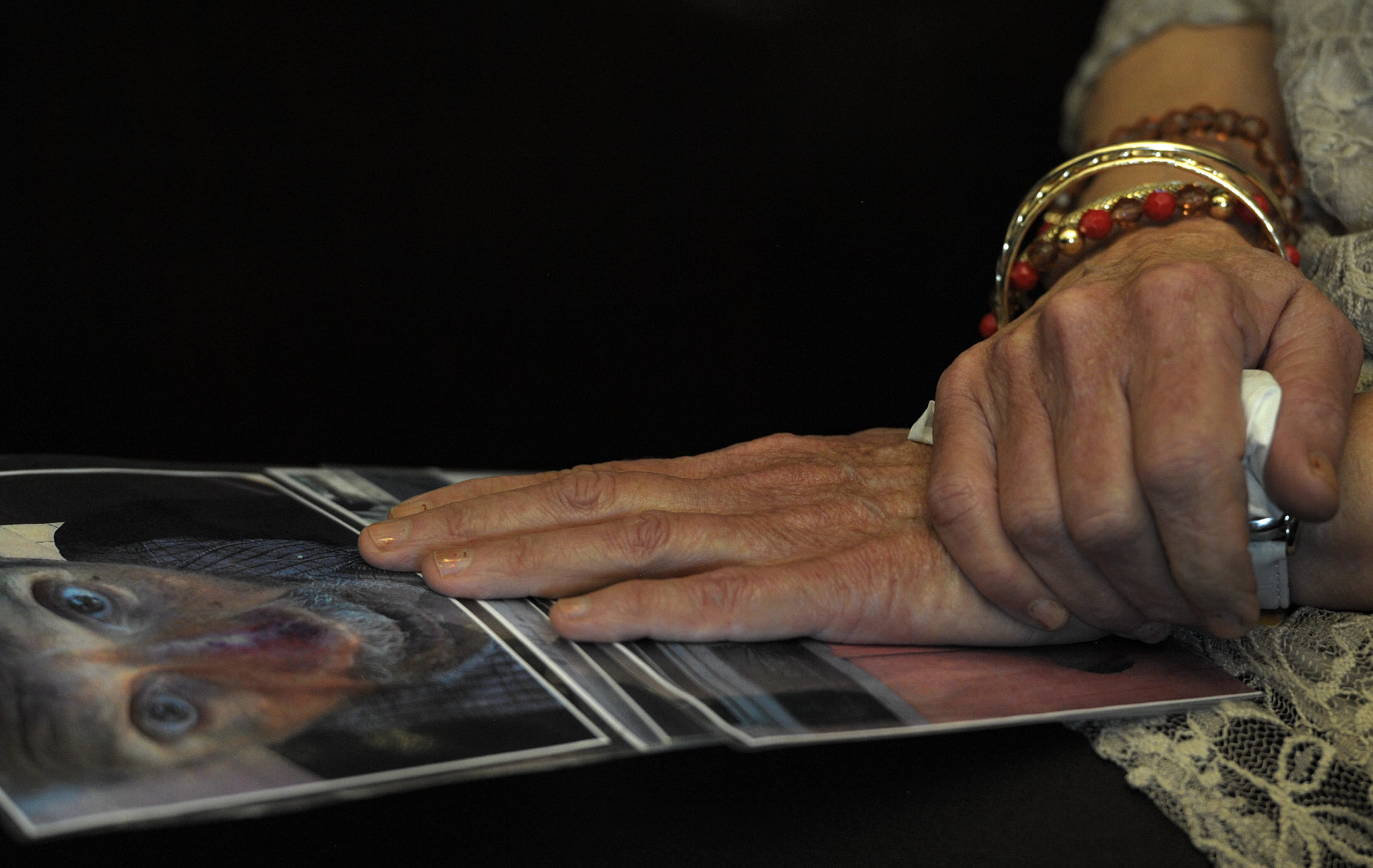

Marie Collitz holds a picture of her husband at the Life Esidimeni hearings. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

But by the next decade the honeymoon period was over. There was a steady decline in the rand’s value and global attention shifted from South Africa as the new rainbow nation lost more of its gloss. Budgets didn’t grow, inefficiencies in the health system couldn’t be ironed out and corruption set in, he points out.

“One never thought that there would be this kind of looting in the health sector,” he says.

But there has been and the GDoH and the national Health Department are hardly ever absent in news cycles exposing corruption, inefficiencies and collapses that go unfixed. Ultimately it comes at a damning cost to patient care, especially the “Cinderella of healthcare”: mental health.

The GDoH has for years now been a “site of capture”, says Kavisha Pillay of NGO Corruption Watch and a member of the National Anti-Corruption Advisory Council.

“The GDoH has been a target for capture for years, even before the term State Capture was coined, because of the large amounts of money that flow through it,” she says.

Intricate webs of corruption

Pillay says there are intricate webs of corruption in the health department. The tangled, multiheaded Medusa includes both syndicates that loot using illegal tenders and procurement deals right through to smaller-scale scams, such as false overtime claims by doctors; data capturers who change details on documents for a few hundred rands or those who siphon off pharmaceutical supplies for black-market trade.

“There’s political interference too,” she says. It includes protected appointments of incompetent and underqualified candidates to key positions. They’re malleable enough to toe the political line, to ensure corruption goes uninvestigated and money is channelled back to political interests. There’s also the use of violence, including assassinations and intimidation of whistle-blowers and investigators, but there’s hardly ever effective action by law enforcement.

Pillay adds that corruption is also this lack of follow-through on investigations or implementation of recommendations meant to clean house and improve patient care and there’s clear tactics to stall and slow down the wheels of justice.

Bereaved familily member Johannah Nqgondwane at the Life Esidimeni inquest. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

For instance, she says, former health MEC Brian Hlongwa was only charged with fraud and corruption during his term in office 12 years after he exited as MEC in the province in 2009. The assassination of Babita Deokaran in August 2021 also remains unresolved. At the time of her death she was acting chief financial officer in the GDoH and a known anti-corruption whistle-blower.

“A key component to fighting these problems is having transparency and access to information from civil society and the public on the development of a budget, to procurement to finalisation of contractions and valuation of services,” she says.

Laetitia Rispel is a professor of public health at the University of the Witwatersrand and has researched corruption in the GDoH. She says key informants for her research over the years report that “corruption has for years been rampant and reached uncontrollable levels”.

Rispel says corruption means blind eyes are turned when it comes to compliance, including with occupational health and safety standards – the kind of basic oversight that should have taken place at facilities where the Life Esidimeni patients were sent.

She adds: “Appropriate systems must be in place to detect corruption and sanction inappropriate, illegal or corrupt behaviour.

“It’s a typical South Africa syndrome, where you go from one task team to the next or one inquiry to the next but we don’t see consequences for people’s action and we don’t see any sustainable change.”

Life Esidimeni Inquest

The judicial inquest into the deaths of the 144 patients is still under way. This legal challenge that resumed in January this year aims to establish grounds for criminal prosecution of Gauteng health department officials and owners of the “care” facilities. It relates to key findings in the Health Ombud’s report.

There are 18 legal teams involved in the inquest. SECTION27 is representing 44 bereaved families. Sasha Stevenson, SECTION27 head of health, says the costs for the State are huge and represents a further drain on taxpayers’ money – an almost ironic circle-back to the supposed “cost-cutting rationale” for ending the Life Esidimeni contract in the first place.

Sasha Stevenson is a human rights lawyer who’s been there, done that and earned the T-shirt. (Photo supplied)

Stevenson adds: “The budget for mental health moves around different line items so it’s often difficult to see what this budget is doing specifically. But we know that in real terms the health budget has gone down by about 5% this year, when there’s already insufficient budget for healthcare needs.

“There’s also obvious huge corruption in the health sector, which also takes away from the budgets we have.”

For her, these intertwined failings make the seven-year process of arbitration, the successful litigation that came with the awarding of damages on the basis of a violation of patients’ constitutional rights and the ongoing judicial inquest even more critical to target systemic dysfunction in the health sector.

“These are incredibly valuable accountability mechanisms. It forces people to come before a judicial officer or an arbitrator and to explain themselves and be cross-examined. Without these, what we would have is a blank space, which is often the case where there has been a huge human catastrophe in South Africa.”

Read more in Daily Maverick: ‘Shine, Doctor, Shine!’ The Doctor who spoke truth to power during Life Esidimeni case

What comes next, Stevenson says, must be continued vigilance and sustained pressure to demand better solutions.

SECTION27, together with the South African Depression and Anxiety Group, the South African Federation for Mental Health, the South African Society of Psychiatrists and the Life Esidimeni Family Committee formed the South African Mental Health Alliance in 2015. They were among the civil society groups that in 2015 were urging the GDoH to reconsider plans to relocate patients or at least to plan better for the department’s so-called Gauteng Mental Health Marathon Project.

“Sustained action is the way to call for stronger leadership, accountability, better budgets and implementation, especially as the GDoH has seen so much churn in leadership that has added to continuous systematic decline,” she says.

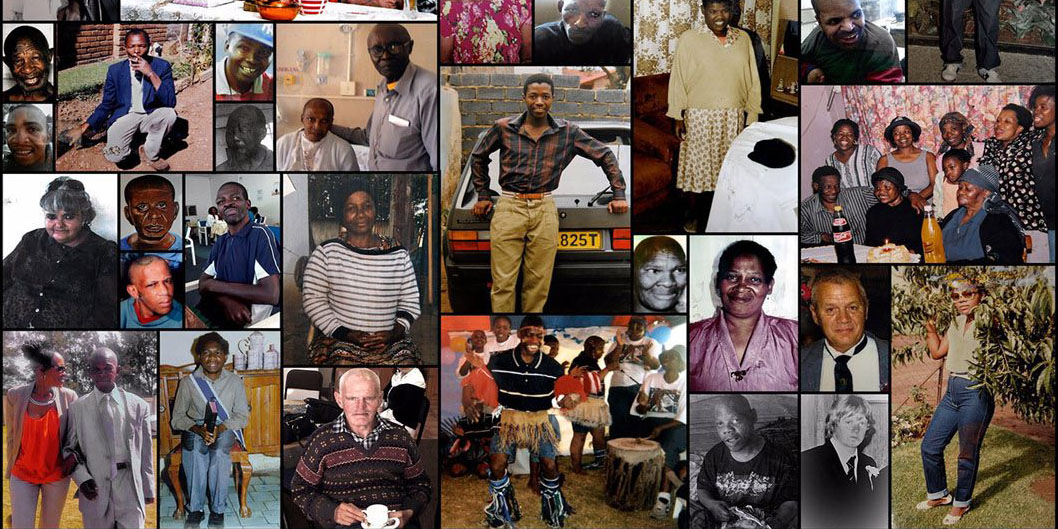

Bereaved families hope the Life Esidimeni inquest will help to bring closure and accountability. (Photo: Joyrene Kramer)

Bertha Molefe, who lost her daughter, breaks down during the media briefing in Pretoria by the Health Ombudsman to announce the final report on the Life Esidimeni psychiatric patients’ deaths on 1 February 2017. (Photo: Gallo Images / Beeld / Felix Dlangamandla)

“As an alliance we need to build on successes, work together and work to break down stigma so that more people do seek care.”

For Leon de Beer, deputy director of the South African Federation for Mental Health, the lessons from the Life Esidimeni tragedy must be a push for a full package of services that allow for effective deinstutionalisation.

Services must include enough beds at institutions to give people proper long-term care when it’s appropriate; tailored services for children and teens; better management to prevent drug stock-outs; and availability of teams of professionals from psychologists, psychiatrists, occupational therapists, counsellors and social workers at primary healthcare level.

He adds: “Nurses and all staff within clinics need to undergo human rights and anti-stigma training. Nurses are sometimes the perpetrators of stigma and discrimination against mental healthcare users.”

De Beer says a new Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Action plan must be implemented without further delays and mental health review boards must be revived. There also needs to be monitoring for adherence and consequences for transgressions.

This collage in memory of the mentally ill patients who died in the Esidimeni Life tragedy was presented at the hearings by SECTION27. (Photo: Section27)

For Tracy these are welcome wish-list items. She’ll keep fighting for them for her patients. But after more than 20 years in public healthcare she knows better than to hold her breath.

In the meantime she says: “I’ll listen to my patient tell me about his dream to open a carwash business or hear what someone else is trying to grow in their garden.”

It’s her way to keep the voices of the dead from growing silent – they never should. DM/MC

Visit the Life Esidimeni website to view portraits of families who lost loved ones in the Life Esidimeni Tragedy as well as to find information on mental health in South Africa.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.