WRITING'S ON THE WALL OP-ED

Thoughts arising from the ideological astigmatism in Pieter du Toit’s ‘The ANC Billionaires’

There was nothing exceptional in what Big Capital undertook to do in South Africa. No ruling class anywhere in the world has ever voluntarily relinquished power to those they used to dominate. Above all, this meant creating ‘ANC Billionaires’.

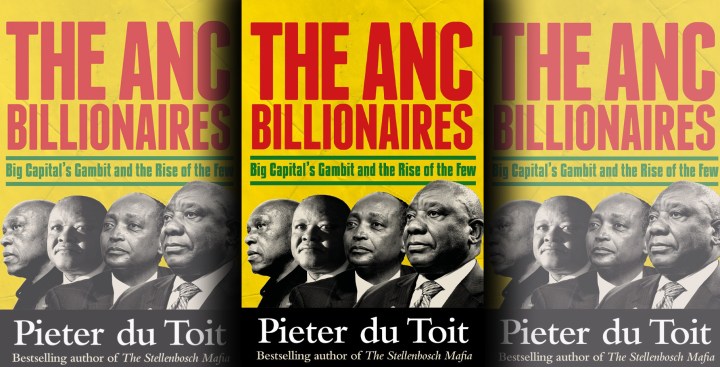

With the title of The ANC Billionaires: Big Capital’s Gambit and the Rise of the Few, the success of Pieter du Toit’s book is not surprising. As a top 10 bestselling non-fiction book in South Africa, many readers of this article may have already read the book. This, however, is not a requirement now.

The book presents three main propositions: that the ANC was a liberation movement without its own economic policy when unbanned in 1994; that, as a substitute, it adopted the outdated economic dogmas of the South African Communist Party (SACP); and that it fell to Big Capital to make the ANC aware of its mistake.

Confounding these propositions, however, is the book’s own, unnoticed, evidence. This begins with the book’s title. It is only incidentally about The ANC’s Billionaires. Big Capital’s Gambit is its principal focus.

Blind Spot 1: The ANC as supposed Economic Innocents

The book creates the impression that, such was the ANC’s singular concentration on political power that (until woken up by the challenge of the EFF) it neglected economic issues. The book attributes this supposed weakness to the ANC’s economic innocence, if not illiteracy. [See: pp. 11, 114, 120-121].

It transpires, however, that the ANC did have economic policies, but they were either “fossilised” [p. 10. Cf. p. xxi] and/or anathema to Big Capital (and Du Toit). Hence the recurring complaint of the ANC having “no modern economic thinking” [pp. xxiii, 3, 10, 22, 29]. Reflecting the book’s own position, Big Capital is thus made the arbiter of what is “modern economic thinking”.

Discarded among the “fossils” are the Freedom Charter [pp. xxii, 11, 13, 31, 120]; the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) – “the biggest and most comprehensive economic policy document to serve as an election manifesto in the world” (Jeremy Cronin, p.111) [Cf pp. 120-21, 124, 127-28, 139]; and Merg, the Macro Economic Research Group’s book of 1993, Making Democracy Work: A Framework for Macroeconomic Policy in South Africa.

Merg provided a coherent and challenging economic basis for the new South Africa. Its problem was that Big Capital disliked it. Intensely. No surprise here, for Merg was a group of largely London-based Marxists [p. 90].

This brings us to the second of the book’s broad themes.

Blind Spot 2: The ANC ‘Marinated in Marxism’ [p.221]

A whole chapter of the book – Chapter 4 – is devoted to the “Marxist-Leninists and fears about the ANC” [Cf .p4], with the SACP supposedly always wanting “to control the ANC politically”. [p.41]

Pointing to the book’s weak historical perspective is that the SACP (then known as the CPSA), when launched in 1921, wished to destroy, rather than control, the ANC.

Moreover, the relationship between the SACP and the ANC remained tenuous at best until after its banning in 1950. Much the same can be said of the period leading up to the ANC’s Morogoro Conference of 1969, which turned out to be the highwater mark of the SACP’s influence, for, by 1972, relations were once again strained. [Tom Lodge’s Red Road to Freedom provides details]

While I acknowledge the challenge of dealing with changing dynamics, policies and influences over the period 1985-2022, Du Toit’s ideological blind spots allow him to claim a “socialist dogma” that allegedly “characterised” the ANC, and “continues to haunt it and South Africa today”. [p.84. Cf. p.129]

Triggering this assessment, both Du Toit and Big Capital — like a bull seeing red — have been inflamed by the mere thought of nationalisation. The Freedom Charter’s allusion to nationalisation sufficing for it being condemned as socialist, even though the word itself does not appear in the Freedom Charter.

The confusion is two-fold. First, they evidently didn’t (or haven’t) realised that the Freedom Charter was deliberately vague; thereby simultaneously satisfying both the communists and would-be black capitalists, the latter of whom required the breaking up of the monopolies dominating the Johannesburg Stock Exchange to create space for what became BEE.

Secondly, they failed/fail to register that apartheid South Africa was already awash with nationalised monopolies. Big Capital and Du Toit are blind to most nationalisations everywhere being government measures to protect — when not subsidising — capitalism. Preventing socialism is the objective, if it figures at all. Nelson Mandela reignited the feared equation between nationalisation and socialism when first released from prison.

Failure to see both capitalist nationalisation and the capitalist economy, with its enduring fiscally conservative policies, allow Du Toit to attribute the South Africa of 2022 to a “failing party of government, characterised by predatory elites completely enamoured with the excesses of capitalism” [p.219].

Saving capitalism

The book doesn’t appreciate the full enormity of the challenge Big Capital faced. (I’m grateful to Colin Bundy for having reminded me of this.) The late 1980s and decade of the 1990s are the book’s main focus. This period is marked by contrasts between what was happening internationally and in South Africa.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, marked the claimed triumph of capitalism. But not in South Africa. Here, capitalism was seriously ill, suffering from multiple maladies of slowed growth, falling investment, rising unemployment and chronic inflation. The international credit squeeze aggravated all these maladies.

Internationally, the powerful trade union movements began unravelling along with workers abandoning the once-powerful communist parties. But not in South Africa. Here, workers’ direct action unbanned the SACP some years before its official unbanning in February 1990.

Reflecting the popularity of the SACP, 19 communists formed nearly half of the ANC’s National Executive Committee in 1991, with party members receiving the first, third and seventh most votes. Eleven out of 26 members of the ANC’s National Working Committee were SACP members. The (new) trade union movement was at the peak of its power [Tom Lodge, Red Road to Freedom, p. 456].

The largest labour federation, Cosatu, was officially committed to socialism; with SACP members occupying many of its senior positions. In 1990, Cosatu and the SACP formed the Revolutionary Alliance with the ANC; the Alliance now known, far less challengingly, as the Tripartite Alliance.

In contrast to North America and Europe, Marxist, or Marxist-leaning, academics were in most South African universities, often in leading positions. Marxist scholarship shaped influential analyses of South Africa.

Yet capitalism in South Africa survived all this. Du Toit partially explains how. This is what gives his book its importance, notwithstanding its inability to recognise that Big Capital’s ultimate success depended on a number of entirely fortuitous circumstances. We will return to this in due course.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

In broader, global terms, there was nothing exceptional in what Big Capital undertook to do in South Africa. No ruling class anywhere in the world has ever voluntarily relinquished power to those they used to dominate. Rather than class suicide, Big Capital preferred PW Botha’s white suicide [p. 25]. In the words of Anglo-American’s then Chief Executive, Gavin Relly “if people accuse us of being self-interested, well, what else would we do? Do you think we would connive in our own destruction…?” [p.31. Cf. p.10]

Indeed, much of the book details how Big Capital ensured it wouldn’t participate in its own demise.

“Big Capital” is a name without hyperbole. How else should one describe a situation where a mere six corporations — led by Anglo-American — controlled 86% of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange? [p. xx. Cf.pp. 12, 135]. Without this concentration of power — and the level of organisation, leadership, and readily available resources it provided, the pre-emptive counter-revolution it led might not have succeeded and certainly not as well as it did [Cf. pp.78-9].

Above all this meant creating “ANC Billionaires”.

The making of black capitalists was early recognised as being “absolutely necessary” by Big Capital [p.xx1. We are informed that “business wanted to survive, and in order to do so, it had to make the black elite owners of capital, even though they couldn’t afford it. The black elite had to own a chunk of the country’s wealth so that the system could survive” [p.xxv. Cf. pp 80, 94, 148, 166, 170].

The “first generation” beneficiaries of Big Capital’s largesse were seemingly unaware of how they were being played. For some, Big Capital’s role was guilt-motivated [p.202]. For Trevor Manuel, BEE was a consequence of the Constitution, not part of Big Capital’s strategy [p.169]. Jay Naidoo, too, when interviewed in 2022, seems innocent of Big Capital’s chess game [p.xxv,xxvii, 107, 122, 141-2].

Making capitalists out of ANC leaders simultaneously meant weaning them off the Marxism in which they were supposedly marinated. This meant re-training them in the ways of the real world, according to the orthodoxy of global Big Capital. This meant trips to the US and elsewhere. Above all, this meant learning at the feet of the IMF, World Bank and other leading bankers. [pp.104, 106, 114-15, 117]

Opportunists and sellouts?

Rather than the ANC having “reluctantly embraced the free market” [p. xxvi], the book details the enthusiasm with which some ANC leaders embraced capitalism [pp. 109, 124, 127, 132, 139, 147, 223].

It is indeed this enthusiasm that gives rise to the now frequent accusations of leaders of either the ANC or SACP, or both, being opportunistic sell-outs. That some of them were, is fair comment. It is also cheap comment.

The book contrasts the way returning leaders were welcomed in the early 1990s with the mass of other returnees. In keeping with the strategy of co-opting the leaders, they were expensively wined and dined, provided with luxury accommodation and in houses often bought for them and when necessary, given suitably senior jobs, etc [23, 71-2, 95-7, 136].

Everyone else was left to their own devices; those who had experienced being streetwise under apartheid being advantaged [pp. 69-72]. Business patronage connected both groups.

The competitive individualising of the once solidarity of collective struggle received legitimisation in 1994 with the enthusiasm with which all the new black parliamentary parties accepted the pay rise immediately awarded to all MPs of the “new” South Africa.

Only a short while earlier, the MPs of the former apartheid Parliament had been attacked for their racism of accepting “First World” pay and perks in a “Third World” country. Archbishop Desmond Tutu was the only notable public figure to express his outrage at this double standard, which was also one of the first decisions of the democratised Parliament.

Facilitating this transition from radical black nationalist or committed communist — often involving the same people — to comfortable capitalist or would-be capitalist was the sense of entitlement they “exuded” [p. xxii]. Arising from feelings of victory — symbolised by the anticipated and then realised first black president — was the expectation, by many of those who had dedicated and often risked their lives in the Struggle against white supremacy, of being owed something [p. xxiii].

Even if all this equates to opportunism, it’s an opportunism made easier by the circumstances of the period and nature of the settlement. The now-representative “I didn’t struggle to be poor” captures the challenges of the time. Big Capital very skilfully adapted its strategy to these fortuitous circumstances.

But was it a sell-out?

The biggest blind spot — the ANC and SACP’s gift to Big Capital

The book’s main astigmatism is its failure to recognise the modest ambitions of both the ANC and the SACP for the peaceful transition to democracy. It consequently overstates what is still Big Capital’s undoubted triumph.

The main gift came in the form of the SACP’s theories of “Colonialism of a Special Type”, and both its related two-stage theory of revolutionary change in South Africa and the idea of the National Democratic Revolution (NDR). The ANC turned the latter into a major piece of its strategy against apartheid.

What they all boiled down to was that the road to socialism must unavoidably include the transitions to a capitalist normalcy, during which the distortions and abominations of the racial capitalism of apartheid are undone.

This is to say, the racial inequalities of white supremacy are replaced by the class inequalities concealed in the shadows of the racial ones. This is the meaning of the National Democratic Revolution. Africans becoming capitalists in a democratic South Africa was the Communist Party’s unrecognised gift to Big Capital!

The party’s secondary gift was its deep-seated and longstanding lack of confidence in its stand-alone appeal. Its position of choice, even when the ANC was accepting some of its policies, was — and remains — to lead from behind.

By noting them now, one is simultaneously recognising that while some party members and supporters might have sold out, this doesn’t apply to the SACP as a party. For the SACP, it was merely being faithful to its own policies. Big Capital has no idea how indebted it is to the SACP! The same applies to Black Capital and its political partners.

None of this, however, detracts from the vital role played by Big Capital in saving capitalism. Had they done nothing, had they been little more than witnesses to their own suicide, who knows what might have happened to the communist’s NDR as the first of its two-stage theory of revolution in South Africa. Allowing the magic of Mandela and the international enthusiasm for the “new South Africa”, who can say what an emboldened SACP might have achieved?

What can be said is that both the SACP and ANC continue to maintain the fantasy of the NDR post-1994; most recently by the ANC’s January 2023 celebration of its 111th birthday. As though the ANC Billionaires are able to — or ever could and would — lead the workers’ struggle to socialism! This is the opportunistic symbiosis between the SACP and ANC in the 21st century.

And none of this is even hinted at by Pieter du Toit. His book is ideologically unable to see that the triumph of Big Capital and its ANC Billionaires endures.

The price is South Africa still stuck in Gear, with its ever-worsening inequality, unemployment, and poverty. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Wow Jeff, you’ve done it again! Stinging analysis from a position that too few, today, write from: deeply insightful outsider.

I don’t see it this way. I think that the whole concept of socialism has changed; it is not what Karl Marx had in mind before 1867, when he still believed in political revolution as a mechanism to the socialist state. Firstly Marx himself changed his theory after 1867. Many of his erstwhile supporters then tried to go on with the idea of revolution, but that also morphed into different things in different theories from there on. In Nkrumaism for instance, the original Marx idea of revolution was influenced by Ghandiism to a transformation that was peaceful. And, as we see in Bernie Sanders’ position in the USA, socialism can be very close to capitalism, only with a lot more emphasis on moral justice. That also took shape here in SA, just in another form. But we should never forget that inside the ANC the SACP is only one faction, while the nationalists, who do want to enrich themselves and their next of kin, play an important role in balancing things out. Then there are traditionalists, capitalists, liberals and a whole host of other factions, making the “consensus” decision making inside the ANC very difficult and resulting in everything taking decades, if it happens at all. The voters tolerated the ANC for 28 years because everyone has some faction that represents their interest in the organisation. But that is also why the ANC can’t properly govern, because the moment the laws are applied, most people are going to be alienated and the futility of such a process exposed.