ANALYSIS

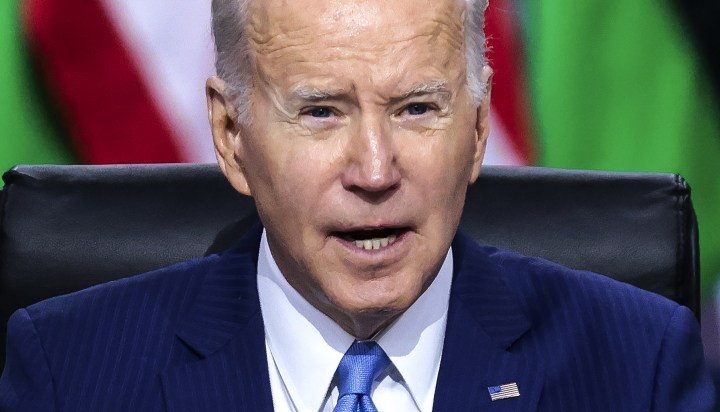

Joe Biden’s US-Africa summit should be assessed on its merits – not on ideology

To dismiss it as merely part of a ‘scramble for Africa’ is simplistic.

The US-Africa summit which President Joe Biden hosted in Washington this month was a “jamboree”, as one US official put it – a huge variety of meetings, initiatives, deals, projects and programmes over three days, designed by the US to reset relations with the continent. Forty-nine African states were represented, 45 of them at head-of-state or government level, as well as the chairperson of the African Union Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat.

Everyone was there except the governments of Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali and Sudan, which were not invited because they have been suspended from the AU for seizing power undemocratically through military coups. Eritrea and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (aka Western Sahara) did not receive invitations because the US does not have diplomatic relations with them.

The many events included a leaders’ meeting with Biden, a security forum with Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin and US AID executive director Samantha Power, a business forum with leaders of about 300 African and US corporations, and countless more meetings of civil society including engagements with the African diaspora, young people, women and other groups.

The summit did appear to revive and reinvigorate US-Africa relations which had flagged during the Trump era.

Investment plans

Biden summed up the summit by saying his administration was planning to invest at least $55-billion in Africa over the next three years. This included loans of up to $21-billion through the IMF to support the recovery and resilience efforts of low- and middle-income countries, and a $504-million compact signed by America’s Millennium Challenge Corporation with Benin and Niger to help finance regional economic integration and trade and cross-border collaboration.

It also included a new initiative called Digital Transformation with Africa, through which the Biden administration aims to invest more than $350-million and mobilise more than $450-million in private capital to boost digital access and literacy across Africa; $369-million in new investments by the US international Development Finance Corporation in food security, renewable energy infrastructure and health; and about $1.3-billion in MOUs signed by the US EXIM Bank to facilitate US exports to and investments in Africa.

The US government programme Power Africa, which is bringing electricity to many Africans, launched a new Clean Tech Energy Network, a collaboration with US clean-tech energy companies and African energy stakeholders that aims to mobilise $350-million in deals. Power Africa also announced a public-private partnership worth $150-million to electrify 10,000 health facilities in Africa.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Next week’s US-Africa summit aims to revive relations but may serve to highlight divisions”

The US government programme Prosper Africa, which links US and African businesses with US government services, said it would invest at least $170-million to increase two-way trade and investment between the US and Africa. It also committed to catalyse$1-billion in exports to the US and an additional $1-billion in US investments in Africa. And so on.

Keeping tabs on this sprawling agenda will not be easy, but Biden also announced he would be appointing former US assistant secretary of state Johnnie Carson – the veteran diplomat who has also been ambassador to Kenya, Zimbabwe and Uganda – as his special representative to ensure all the US-Africa summit commitments were implemented.

Persistent scepticism

Inevitably, though, not everyone on this continent was favourably impressed by such deepening relations with the US.

In Africa more widely and perhaps particularly in South Africa there remains a persistent strand of scepticism about anything the US does here. Such sceptics saw the summit as essentially just an effort by America to play catch-up and try to edge ahead of its global rivals in a “new scramble for Africa”, as South Africa’s deputy foreign minister Alvin Botes put it in a webinar on the summit held by the University of Johannesburg, titled “Washington woos Africa: for better or worse”.

To get some sense of the logic which he brought to the debate, though, one should also note that Botes decried the fact that with only 44 UN members, Europe had 13 nations represented in this year’s soccer World Cup, while Africa, with 54 UN members, was represented by only five nations. This Botes saw as “an indication of the uneven balance of power that finds expression, even through the issue of sports diplomacy”.

To see the World Cup as a representative international body, like the UN itself or the IMF or World Bank, is patently absurd. The next step in this train of thought would be to argue that Africa has never won the World Cup and so should have been simply gifted the trophy this year. This was a caricature of the sort of un-analytical thinking which too often bedevils debate about Africa’s relations with the world.

Nontobeko Hlela, a researcher for the South African office of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research, a Global South think-tank, detailed in the same webinar, what she saw as evidence of this new scramble for Africa. This purported evidence included “the biggest embassy building boom anywhere in the world”. Between 2010 and 2016 more than 320 new foreign embassies had been opened in Africa, Hlela said. Turkey alone had opened 26.

On international military interest in the continent, she said that China had become the biggest arms seller to Africa, signing defence technology agreements with 45 countries; Russia had concluded military deals with 19 African countries since 2014; all the rich Gulf states were building military bases in the Horn of Africa and hiring African mercenaries; the US has 29 “known” military facilities in 15 African countries; France had military bases in 10 countries on the continent and Turkey had built its largest foreign military base, in Mogadishu, Somalia, in 2017.

Hlela also mentioned the American and French military interventions in Libya in 2011 and the French intervention in Mali in 2013. She also cited France’s establishment of the G5 Sahel group with Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger in 2014, which other European powers were supporting as well as increasing their presence in the Sahel more generally, to counter Islamist terrorists and try to staunch the flow of migrants into Europe. The US had built an “enormous” military base near Akadez, Niger, from which she said it was conducting drone strikes and aerial surveillance missions across the Sahel and the Sahara Desert.

Hlela cited other examples of what she regarded as the new scramble for Africa, including China’s establishment of a military base at Djibouti and Beijing’s extension of its military influence well beyond this base, into Africa. She said the People’s Liberation Army had conducted exercises in Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana and Nigeria. In turn this growing footprint had alarmed other Asian powers so Japan had enlarged its military base in Djibouti, while India had been building a network of radar and listening posts around the Indian Ocean

Russia too was extending its military influence across the continent, beyond the Central African Republic where its presence was most conspicuous.

Lacking nuance

This growing diplomatic and military presence of global powers in Africa is certainly noteworthy and should be assessed. But how one does so is important.

It is not enough, as Hlela did, to simply dismiss it, without analysis, as an unseemly goldrush by all these powers to seize Africa’s material resources and to abuse the continent as a random battleground for its own war on terror.

Greater nuance than that is required in interpreting these events. For one thing, one can hardly equate the opening of embassies with the building of military bases. Would Africa like foreign governments to shut down all their embassies in a reverse scramble out of Africa?

And more nuance is also required in interpreting the growing military presence, worrying as it might be. The proliferation of foreign military bases in Djibouti, for example, began as an effort to counter Somali pirates in the Gulf of Aden. And the efforts since then have been largely directed against violent Islamist extremists, surely an enemy to all civilised people.

Hlela also had a problem with the correct sequencing of cause and effect. She noted, for example, that the more the US has tried to stabilise the continent, mainly through training of African government militaries, the more militancy has spread, and the more insurgencies have proliferated, the more terrorism has spread, the African states have failed and the more unsettled the continent has become.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

It is one thing to suggest that the counterterrorism efforts by the US and other foreign powers have failed to contain or to eradicate Islamist terrorism and other destabilising forces. That may or may not be true. But it is quite another thing to suggest, as Hlela clearly does, that the US and other counterterrorist operations have been the cause of the rise of violent jihadism and other ills in West Africa and the Sahel as well as elsewhere on the continent.

Perhaps some jihadists have been inspired to take up arms to expel the foreign forces. But there is a host of more fundamental reasons that Islamist extremism is spreading in this region and further afield on the continent. Most of those have to do with very poor governance and mishandling of Islamic fundamentalism by African governments themselves. To suggest that a growing foreign military presence has led to growing extremism is a bit like saying the large number of sick people at hospitals is a result of the presence there of many doctors. The causality is inverted.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Islamic State insurgents could target South Africa, warns President Ramaphosa during Pretoria conference with Kenya’s Kenyatta”

Hlela concluded, sweepingly, that through this “neocolonialism” of proliferating military bases and embassies, foreign powers were seeking to fragment Africa and to undermine the essential principles of pan-Africanism – political unity and territorial sovereignty. “We cannot sit by and watch this new scramble happen to us as if we have no say,” she said, proposing that Africa should negotiate with the world with one voice.

Critical global challenges

It is true, of course, that Africa has a voice, it has power and it should use it more. But how it exercises it is what counts. Most of the continent’s ills derive not from Africa failing to speak with one voice, but from the way individual African governments treat their own people – including the often corrupt deals with foreign corporations for the extraction of resources in which African governments are often complicit,

Nevertheless, critics like Hlela ignore the fact that a key part of the new Africa strategy announced by Blinken in South Africa in August was precisely to amplify Africa’s unified voice in addressing critical global challenges such as climate change, pandemics and terrorism. This was why Biden announced at the UN General Assembly this year that the US believed Africa should have a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, and why he later said the AU should become a permanent member of the G20. This was not consistent with Hlela’s contention that global powers are determined to fragment Africa.

Though it is notable that neither Russia nor China – which like to present themselves as Africa’s true friends – have supported those initiatives.

Africans are fond of reminding others that Africa is not a country. But they also have to acknowledge that foreign powers are not homogenous either. Different powers also have different interests. Many are certainly trying to tackle jihadism at source to prevent it from spreading – especially into Europe. But it is obviously also in Africa’s interest for jihadism to be contained and hopefully defeated. Russia’s military and in particular its private military company Wagner seem to have other interests, at least in addition to those, such as frustrating Western governments – particularly France – in Africa and directly earning natural resources in exchange for propping up undemocratic African governments. No doubt Western governments are also now competing more aggressively with China and Russia and others for rare minerals like lithium and coltan, which are growing increasingly important for building modern technologies such as cellphones, electric vehicles, renewable energy generation and sophisticated weapons.

But it is not whether these minerals are extracted that is important. Bartering them for unaffordable loans or in exchange for opaque military support to prop up autocrats, is not a good idea. Transparent partnerships with public terms that benefit host populations is obviously the better way.

Hlela’s plea for a kind of pan-African autarky was also outdated.

As David Monyae, director of the Centre for Africa China Studies at the University of Johannesburg, pointed out in the same UJ webinar, the Organisation of African Unity’s (OAU’s) Lagos Plan of Action for the economic development of Africa decided back in 1980 to increase Africa’s self-sufficiency and to minimise its links with Western countries by maximising the continent’s own resources.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Australia’s new Labor Party government reinvigorates relations with South Africa and Africa”

But Monyae also noted that when the AU superseded the OAU in 2002, it took a fundamentally different approach, realising that Africa could not develop on its own and that it could only do so in partnership with the rest of the world.

The implication is that Africa must become more skilful at managing its relations with the foreign powers that are growing more interested in the continent. That might sometimes happen at the continental, AU level. But more consequently it will happen country-to-country.

And where those individual African countries are well-run, open democracies, serving their people, their relationships with foreign powers will also be much more likely to serve the interests of their people. DM

Comments - Please login in order to comment.