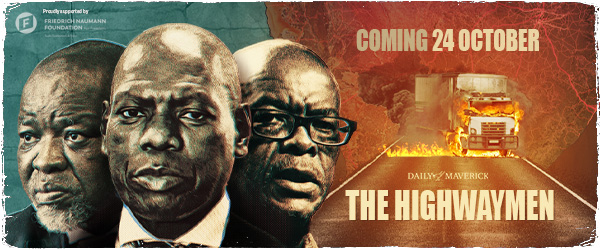

THE HIGHWAYMEN TRANSCRIPT

Episode 5: Ace – mister ten percent

In December 2022, the 55th — and possibly last — elective conference of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress will take place against a backdrop of sociopolitical chaos. In the limited audio documentary series, The Highwaymen, investigative journalists Richard Poplak and Diana Neille take a road trip across South Africa in search of answers to how the country got to this breaking point, and how the lives and careers of three senior ANC figures — Ace Magashule, Gwede Mantashe and Dr Zweli Mkhize — may be representative of the rise and stumble of our once vaunted democratic project and, by extension, liberal democracies everywhere.

Continuing with the Elias “Ace” Magashule saga, Diana Neille and Richard Poplak delve into the alleged political murder of Noby Ngombane, a key administrator in the attempted clean-up of the Free State during the early zeroes. His assassination is an example of what can happen when, in the binary gap between opportunity and poverty, liberal democracies begin to swerve toward gangsterism. The tragedy reverberates through the years, as if the sound of the gunshots has never faded.

Listen to the podcast here

Beatrice Marshoff: I’m Frances Beatrice Marshoff. I was born here in Bloemfontein… I can say I’ve always been involved with the struggle… Since I can remember, it has been a part of me.

*I was appointed by the president as the premier of the Free State. I can say it was not a happy feeling, because… Ace was sitting here waiting to be appointed as a premier, and then he was not appointed. It meant that there was a lot of trouble. There was a lot of discontent.

Diana Neille: The year was 2004, and in came Ms Marshoff — a registered nurse, former MP and former Member of the Executive Council for Social Development in the Free State, who was one of the principled New Dawns that appear on the ANC’s horizon every now and again.

She was clean, and she was unconnected to any of the factionalism that was roiling around her. In short, an ANC unicorn.

It’s very important to pay attention to what happened when President Thabo Mbeki tried to bring the Free State under control by installing Marshoff and snubbing Magashule.

Beatrice Marshoff: For me, the most important part was that we needed to bring stability. We needed to bring an ANC that people could believe in, that they could see that this is the ANC that we’ve voted for, and that we will see bringing about the changes to the people. And I think that was essentially what we were hoping for.

I think the biggest problem was that I didn’t allow the opposite group to intimidate me. I showed that I was not going to be disconnected from my position within the party, as I knew that they wanted to have it, and that they couldn’t have it. They then felt that they had to fight me.

I brought with me, from social development, a few people that I could trust. Noby was then the person responsible for economic development. I took Noby into the office to help me, because I needed someone… that understood the principles of the ANC, and that would not back down for these guys.

Diana Neille: Nokwanda Ngombane worked as a personal assistant to the premier, and helped Marshoff set up her new administration.

Nokwanda Ngombane: Noby was the key person here and he felt that if the Free State modelled the national government model of a report-back system, of planning with the policy units, there would be much [more] coherence and direction for the government and Beatrice would have more control, and a better oversight function. And the Free State… would be advanced.

Actually, that was the time that I could see the light in his eyes again, where there was this real prospect of… him participating in a meaningful way for the people of the Free State.

Richard Poplak: So, in other words, a more efficient government.

Nokwanda Ngombane: Well, yes, yes. A more efficient government, a more responsive government.

Diana Neille: It was certainly a nice idea.

Beatrice Marshoff: Ace wanted to be seen. And I think… the whole thing was that he was preparing himself for the ultimate thing — for president. We knew this was Ace’s hope and this was his ambition, but he just did not have the gravitas to stand and become a president. But the way he manipulated people was the strongest part of it. And unfortunately, people still believe that, with Ace, everything is possible, and they will get to where they want to be.

Listen to the podcast here

Ace Magashule: Well, interacting with people is very important. Being humble, hard work, consulting communities… We believe in persuasion, we believe in engaging people and persuading them to see the other side…

Richard Poplak: As shadowy figures in the Free State tried to undermine the Marshoff clean-up campaign, Magashule was working to shore up his own standing and stature within the province. This meant fundraising, regardless of its ethical or legal constraints.

Marshoff, as Premier, had to colour within the lines. Magashule didn’t. Pat Matosa went on one of these fundraising jaunts with Magashule… It was his first and last:

Pat Matosa: We came to one well-established businessman. It [was] a white chap, generally liking the ANC. I think we were requesting either fifty or a hundred thousand. And the man said, “I don’t have that kind of money, I have only twenty.” Ace refused. You know, when I saw that man breaking down and cry[ing], I said, “Ace, no, we can’t do that.”

He pointed a finger at me, and [said] I must keep quiet, he wants that money. I said no. He insisted.

Richard Poplak: So you’re saying he shook this guy down.

Pat Matosa: My God, the man was crying. The man was crying in front of me. Then I was making some effort in intervention, and saying, “no, we can’t do it”. He said I must keep quiet — “this man is having money. I know he’s having money, he must take it out”. That man broke down and cried and counted the money in clips and gave [it to] us. I did not even touch it. I said, “no, keep it, man. I don’t want that. I mean, you can’t do that.”

So the man become[s] very cold when he’s pursuing a mission. He does not blink.

Richard Poplak: But not just the ANC — indeed, for all political parties that contest elections both internally and externally, the whole democracy machine is fuelled by money. It’s not always obtained via a shake-down, but lobbyists, tenderpreneurs and consultants all have their ways and means.

Mbeki’s elite cabal could solicit funds in the wood-lined boardrooms of the Sandtontariat, and from corporations and high-minded institutions abroad. Magashule’s cabal — the ANC’s less established figures — had to employ alternative means.

This is what Beatrice Marshoff and Noby Ngombane were up against, as they tried to focus on governance and service delivery.

Nokwanda Ngombane: Beatrice was quite a delight to work with… She’s impatient in terms of wanting things done. To work with her was to be on the roll. I mean, I lived on coffee those years. By six o’clock we’d hit the road… Here in the Free State in particular, I remember the municipalit[ies] gradually going down. I remember… almost the very initial uprisings were in Phumelela in 2000.

So I decided to go to Phumelela, to Vrede, those towns, to actually go and interview the people there, and there were service delivery protests. Phumelela local municipality was not functioning. ANC councillors would not come. Nothing was working. So the residents were frustrated. And then there was this move to mute that which did not fit into the ANC way of thinking.

[Beatrice] had decided then to formally form this policy coordination unit. And after this formation, Noby left the department of economic affairs into the Premier’s department to head that, and started developing the systems and the processes of making sure that funds like the municipal infrastructure grants and the expanded public works programme’s funds were centralised there.

Ace Magashule, his group, they started persecuting him, and fighting with him about anything and everything.

Diana Neille: As our colleague Pieter-Louis Myburgh notes, on 21st of March 2005, there was a meeting with Magashule’s people and Premier Marshoff. There was a cabinet shuffle looming, and word is that Magashule was going to be booted as MEC of agriculture. Noby’s name kept coming up as someone who had undue influence over the Premier.

The next day, this happened.

Nokwanda Ngombane: Noby was a very emotional person. It was very painful to watch him break down… literally almost every day.

Noby could be a very dramatic guy. He told me he’s definitely going to die. They’re absolutely going to kill him. He was scared all the time. He knew, he knew — in fact, on the day of his killing, he came home around seven and arranged for us to watch a movie with him.

Diana Neille: The movie Noby chose was called Ray, the story of the musician Ray Charles. The family gathered on the couch, slid the DVD into the player, and began watching.

Nokwanda Ngombane: The DVD starts with Ray’s brother dying, and then there’s this coffin, and then Ray’s mother is literally crying and Noby says, “Oh, black people, they do this everywhere. Promise me you’re not going to do this when I die.” I’m like, “Huh. Okay. Whatever”. He says, “Promise me, promise me!”

Diana Neille: Noby kept interrupting the movie to tell Nokwanda how he’d like his funeral to be planned. To make her promise there would be enough food for everyone, especially meat. He hated funerals that were stingy on the meat. He made her swear no ANC politicians would be allowed to attend, and to tell those gathered at his funeral the truth about his death.

Nokwanda Ngombane: So he made me make those promises. And I said, “yes, that’s fine. Okay. Can we watch the movie now?” And we watched the movie. Then there was a car coming in and, because we were living in a cul-de-sac… He got up. I thought [he] was going to the kitchen. And then the next thing we had gunshots and I saw my daughter running and well, gunshots are gunshots. We ran for cover, that’s the first instinct.

Then I saw my daughter, and then I went for the phone. I noticed that my car is actually by the door. So I literally pulled him up, dragged him, called for my brother who was there to come and help, and my siblings. I dragged him to the car, took him straight to the Mediclinic.

I calculated that, if it’s six minutes thereabout to get to Mediclinic from our place, if I don’t stop at the robot, I drive at breakneck speed, I would make it in probably three, four minutes. I don’t know how long it took to get there. But I went straight into the emergency… And I left Noby in their capable hands. And I took a deep breath and I went on my knees. Begged for his life.

And I got that gut [feeling] knowing that he’s not going to make it.

I wanted to go to that emergency room to check on what’s going on… Because I believe that a person, if you don’t let them go, they will hover around, [if you] don’t give them permission to leave. And I believe that Noby was and is my soulmate. So I went to him and I felt him and he felt cold. And I told him that, “you know what, if it’s time to die, it’s ok for you to go. I don’t know how we’re going to make it, but I believe we’ll make it.” I kissed him and I left the room.

Richard Poplak: This is how it was in Bloemfontein, on March 22, 2005, with Noby Ngombane. Everyone — very much including Noby — knew that he was a dead man walking. And no one could or would stop the bullets. Five of them, shot into his body, in front of his young daughter.

In this chronicle of a death foretold, Noby was marked the second he started to clean up the province. Everyone who knew him, feared for him. And their direst predictions came true.

Beatrice Marshoff: Going there, going to the hospital, it was like, where’s Noby? There’s no Noby, because Noby is lying in the side room, his chest is open, he’s dead. And that was just too much for me.

Nokwanda Ngombane: Noby was declared dead at half past ten. By that time, I think there must’ve been a second set of police… We left the hospital, came back home… The house was cordoned off… And then the third set of policemen came and I literally told them… to go to hell. I won’t give a third interview on the night of Noby’s death.

We prepared him for the funeral… Everything had to be according to Noby’s wishes. I was getting ready for the speech. For me it was important to say what I believed to be true — which I still believe to be true — that Noby was not killed by a random person. It was a political hit.

So I said those things. I didn’t break down… I was wearing a white dress… And I pointed an accusation, according to them, at the mighty ANC.

That was [the] onset as far as I am concerned of giving a blank cheque, that anything and everything here in this land of the ANC government is permissible.

Richard Poplak: Back to Pieter-Louis Myburgh.

Pieter-Louis Myburgh: I think the kind of bizarre effect of a development like the Noby Ngombane murder, is that Ace Magashule wouldn’t even necessarily have to have been behind it, to have benefited from it.

So when the murder occurs, there’s this kind of perception in the province, at least, that somebody from that grouping, was involved. Now, it might not be the case… It’s never been proven. But, ultimately, Magashule does benefit from it, because now there’s this culture of absolute fear, there’s this belief out there that somebody within his grouping had been responsible for the murder.

Richard Poplak: The paranoia governed everything. Meanwhile, the war between Mbeki and Zuma would culminate in 2007 in a place called Polokwane, at the ANC’s 52nd elective conference.

This is where Zuma, now with hundreds of charges of corruption hanging over his head, would be cheered into the presidency, and where Mbeki slunk away into the wilderness, denied a third term as ANC president, to which he believed he was entitled.

News clip: The number of votes received by comrade Thabo Mbeki: 1,505…

Richard Poplak: The outcome of that conference defines every aspect of South Africa today.

News clip: The number of votes received by comrade Jacob Zuma: 2,329.

Richard Poplak: One of the winners in this conference was Magashule.

Pieter-Louis Myburgh: [T]he deal is put on the table… if you back us at Polokwane to ensure that Jacob Zuma becomes President, you’re finally going to get that seat at the big table, being the Premier, you’ll be elevated inside the ANC nationally, of course, because your premiers also kind of hold that power within the organisation.

The Free State backing plays a role in Zuma coming to power… Magashule becomes a Premier of the province, and the path is open for the likes of Atul Gupta and his family to come alongside Jacob Zuma and plunder our resources for the next decade.

Diana Neille: Have we not mentioned the Guptas yet? The three Indian brothers from Uttar Pradesh who were the superstars of State Capture, the men who bankrolled Zuma and flushed money into the ANC? They were corruption made manifest — the middlemen to the great big middleman in the sky.

Beatrice Marshoff: It became even worse than what it was before… There was just this feeling of, they have to surround me with people that would… disseminate the way things were going, and there was a lot of pressure on me to step down at some stage. They put me down and they gave me such a lot of crap, that, eventually, I just felt that… there wasn’t enough to keep me there.

But I always knew that Ace was going to be the undoing of the ANC in the Free State. He wanted to be a premier at all times, and his post as a premier was the most disastrous for the Free State. The things that he did, and the things that happened… under his premiership, are never things that we wanted to see happening in the Free State.

Listen to the podcast here

Nokwanda Ngombane: So the politics changed, it became… Ace Magashule’s backyard, and whoever disagreed with him, knew that they were going out in their coats. In fact, they had a term called The Refrigerator… so they knew that they had to listen to him, and if they didn’t do what he wanted to do, they would go hungry.

So the politics became the literal politics of the stomach, and not just the stomach, really, because how much… does the stomach really need? It just became greed, in its most obscene way.

Diana Neille: The stage for Magashule’s eventual success in taking power in the Free State was set by the assassination in 2005 of a public official. Noby Ngombane’s death should’ve dogged Magashule into the premier’s office, but magically, it never did. A very different investigation unfolded — a horrific perversion of the meaning of justice.

In July 2005, Nokwanda, her siblings Bongani and Thanthiswa, and two cousins Vuyokasi Mlambo and Sephumle Booi, were arrested and charged with Noby’s murder. The public turned on them, and the authorities.

Nokwanda Ngombane: For Noby’s case, it’s very interesting — the top brass… No resource was spared by the state, because there was even a captain from Pretoria who came here, and was also involved in the investigation… They brought an expert from Scotland Yard… With the inquest documents, I got to see that I was followed every day.

They had no basis for suspicions… I was always going to be a scapegoat. I was always going to be arrested. And I did all the right things that lay the grounds for them to say I’m the suspect.

So there was… there was no time for anything, but just constantly fighting for our lives. And I literally, for those years, well that’s first from the time Noby died, until after the charges were dropped 18 months later, I lived at the mercy of whichever friend felt like I needed R1,000 extra.

And I now know… that they probably… thought that I would take it lying down. That was a bad, bad move, from their side. Thank God they didn’t know me… Because maybe they would have been harsher, if they’d known that I would mount a fight.

A lot of the people who were misled — because they were given a certain narrative, and allowed to go on a wild goose chase — they did apologise. They were given an opportunity there, in court, to apologise. And the direct question was… asked, if there was pressure, politically. And a direct answer had been, yes, there had been pressure to arrest us.

Richard Poplak: The unravelling was beginning.

Magashule is a model for what can exist in a liberal democracy. He’s the gangster politician, buying up support with patronage, making sure his enemies are out in the cold, with the implicit threat of violence draped over him like a cloak.

He adheres to the Russian model, but also to the model of the Tammany Hall party boss in New York City back in the old days, which was the engine of mafia-style graft and corruption in New York State by the early 1900s, where it served as the local conduit of the Democratic Party for almost 200 years. These guys are making something of a comeback.

Ace Magashule helped set the stage for a move from ideological contestation, to divisions, to factionalism, into a programme of institutionalised corruption, and then beyond that, into a formalised gangster state.

As always, though, there is a very human cost to this continuum. Seventeen years after Noby Ngombane was assassinated, that cost is still very, very dear.

Nokwanda Ngombane: Sitting here now, on the first of March, 2022, I know that I did not hold it together, actually. At all. I went into a complete shutdown… Survival mode. Underneath that anger, was the pain, was the trauma. Sadness, anguish… What still pains me about this lack of justice is his children.

Richard Poplak: Ngombane’s daughter, Zandile, who witnessed his murder at the age of five, could not move on from the loss of her father. She recorded this song as a teenager.

Dance With My Father, by Luther Vandross. Sung by Zandile Ngombane

My daughter, Zandile, took her life when she was 18, in 2018. It ripped her apart.

My son, Khanya… only now, at 24… is starting to open up about the pain of growing up without his father. There’s no justice in whatever form. We were never able to mount even a civil case against the state. I didn’t have resources.

The pain, for me, is just… The loss becomes compounded. I literally, I just don’t have words.

Richard Poplak: You know, it makes me feel like you’re talking about all of us, in some way, about how we feel about this country, that there’s a corollary between what happened to your family and what’s happened to South Africa.

Nokwanda Ngombane: Yes, definitely. The ANC was responsible for Noby’s death.

I actually want to go to the grave of this guy… my soulmate… who introduced me to politics… and ask for permission to get cleansed of the lies that I bought into.

For people like me, who have these communities that are becoming despondent… nobody has been ploughing for the last couple of years, because people are waiting for manna.

And the manna is not coming. DM

Fact check and additional research by Sasha Wales-Smith.

What shameless crap the ANC has birthed into our democracy. Still, now, there is fear if you are outspoken you’ll be taken out and you will know who’s behind it but the police will never charge anyone.

What a sad tale! It’s disgusting. And Ace and his accolades are still walking free. I am ashamed to be a South African.

It’s life or death in this organisation. This criminal organisation.