HEALING A NATION OP-ED

Overcoming historic trauma – all South Africa needs is love (and compassion)

Fostering sustainable development, quality democracies and relatively peaceful societies that emerged from violence, cannot happen without the former oppressed communities inculcating a mass culture of individual self-love, and consistently electing leaders who operate from love, who have compassion for others that stretches across ethnicity, colour or region, and is not based on self-interest.

Colonialism, apartheid and systemic racism, and of chronic poverty which continued under many African governments following independence, undermine the agency of victims, the capacity of individuals to appreciate their own power, the opportunities in their midst and the alternatives they have to fulfil their potential.

More broadly, agency is the ability to act on one’s own will, despite the constraints of belief systems one has grown up with, others’ perceptions of one and a limiting environment. Quality development, democracy and societal peace following past country trauma is not sustainable without large doses of agency at the individual and collective level.

Societies that have emerged from colonialism, apartheid, civil war, systemic racism and long-standing chronic poverty, experience trauma not only at the individual level, but also mass trauma at a collective level. The trauma undermines the agency of the victims – at the individual and collective level, and often their offspring for generations.

Restoring the agency of victims of oppression is one of the key conditions for sustainable development following terror regimes.

Traumas from terror regimes or meted out by violent groups to others deny the humanity of those they oppress, assault and terrorise, resulting in broken individuals, communities and societies. Mass trauma damages indigenous cultures, collective identities and individual self-worth. It undermines self-esteem, batters self-confidence and distorts emotional management. Many victims develop inferiority complexes.

Fundamentally, it undermines self-love, which often leads to self-hatred and victims often who seek invisibility, rather than expression of their full self. It disfigures the sense of self, undermines healthy familyhood and distorts interpersonal relationships.

All these ultimately batter the agency of victims.

Shattered assumptions, existential insecurity

In his theory of shattered assumptions, Ronnie Janoff-Bulman argues that people interpret the world based on a set of assumptions about themselves, others and the world. This provides a view of how the world operates and how to interpret what happens in the world and one’s role in it, a process which allows one to function as a healthy human being.

One would believe that one is a worthy human being, of value and deserving of fair treatment. These assumptions give meaning, self-esteem and centredness to one’s existence. Trauma, whether colonial, apartheid or chronic poverty, disrupts such assumptions – as one now cannot make sense of what is happening around oneself. It distorts the individual and collective understanding of the world.

For example, sufferers of such unprocessed trauma may make decisions, in their personal life, whether choosing intimate partners, or in political life, voting for leaders or parties that go against their own interests, or in protests, destroying communal infrastructure they need for their own development.

A number of researchers, including Helen Epstein in 1978, in her seminal book, Children of the Holocaust: Conversations with Sons and Daughters of Survivors, have argued that the impact of sustained physical, violent and psychological trauma can be transferred across generations – even to those who have not experienced the original trauma.

(Image: amazon.com)

Colonialism and apartheid left black South Africans with massive “existential insecurity”, roughly meaning, paraphrasing the term from Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, “a persistent, generalised sense of threat and unease” because their survival was systematically threatened on every level – personal, family, community, culture and nation.

They left ordinary Africans across the continent with pervasive, deep-seated and persistent feelings of anxiety or angst, insecurity and vulnerability.

Slavery, colonialism and apartheid destroyed the “familiar and trusted social benchmarks” which existed before colonialism and apartheid, whether cultural, individual or social, and anchored individuals, communities and societies, giving them a sense of self. For many Africans, slavery, colonialism and apartheid have induced the “feeling that the self has no foundation” anymore.

Read more in Daily Maverick: “African nations must base foreign policy on domestic interests, not past ideological ties”

Rapid mass industrialisation, economic and cultural globalisation and technological change have transformed black societies, who mostly have been pre-modern societies, and which had to adapt quickly. This has reinforced the process of “dislocation” – whether cultural, individual or social, and compounded the African sense of “existential insecurity”.

Small black elites taking power in the post-apartheid and post-colonial period from former oppressors, but then governing only in the interests of themselves, their comrades and their families – leaving the vast majority of their fellow former oppressed behind – have amplified the existential insecurity among the formerly oppressed peoples.

In fact, the post-independence and post-apartheid chronic poverty, insecurity and persistent and violent threats to individuals, families and communities – of genocide, arbitrary official violence and family destruction – under African governments which were expected to bring a new post-independence and post-apartheid sense of serenity, reinforced the “existential insecurity”.

Impact of ‘existential insecurity’ on the individual

The “existential insecurity” has played out in a number of ways at individual and collective levels.

Frantz Fanon, the Mauritian-born Algerian activist, warned that colonialism and apartheid had scarred the psyche of victims – their individual personalities. Fanon pointed out how institutional racism scars the black “psyche”, often causing inferiority complexes, self-hatred, low self-esteem, aggression, anxiety and depression.

Albert Memmi, the great Tunisian writer, describes how very few aspects of the lives and personalities of many of the oppressed peoples were “untouched” by colonialism. “Not only my own thoughts, my passions and my conduct, but also the conduct of others towards me was affected”, wrote Memmi.

Martha Cabrera, the Nicaraguan psychologist, talks about “multiply wounded” societies, which as a result of “permanent stress lose their capacity to make decisions and plan for the future due to the excess suffering they have lived through and not processed”.

At the individual level it has led to inferiority complexes, self-hatred, lack of self-love, low self-esteem, high levels of anger, deep-seated angst, chronic insecurity, and a loss of sense of self, lack of self-love, their own sense of agency. It has led to violence against self, intimate relations and outsiders.

Lack of self-esteem, inferiority complexes and lack of self-love lead to many losing their agency. It causes high levels of mental illnesses.

Many victims may apply colonial and apartheid stereotypes to themselves – fostering a negative concept of self – and undermining their own agency. The self-acceptance by some black people of racism against them often fuels self-doubt, self-aggression and self-hate. It can lead those afflicted by internalised racism to dehumanise other blacks, whether from other ethnic groups, religions or for other countries.

The capacity to love

Traumatic experiences can often lead to one not believing in love and to see relationships, whether intimate, friendships or business, as transactional, depending on what one can get out of it. Susanne M Dillmann writes that “the ability to freely give and receive love is a fragile skill, which traumatic experiences can all too easily dent or damage”.

Experiencing cruelty from others can harden a person, not to trust others again, to assume that others are out to exploit you and to remain a victim of past injustices. For another, some victims of colonial, apartheid and chronic poverty, may continually engage in toxic love, including emotional and psychological abuse and physical violence.

Others may have warped ideas of love, which involves controlling those they love, using violence as a tool in their intimate and personal relations and unleashing violence against partners who want to leave them. Yet, to give healthy love – and be open to receive it, despite traumatic experiences – is crucial to healing from traumatic experiences.

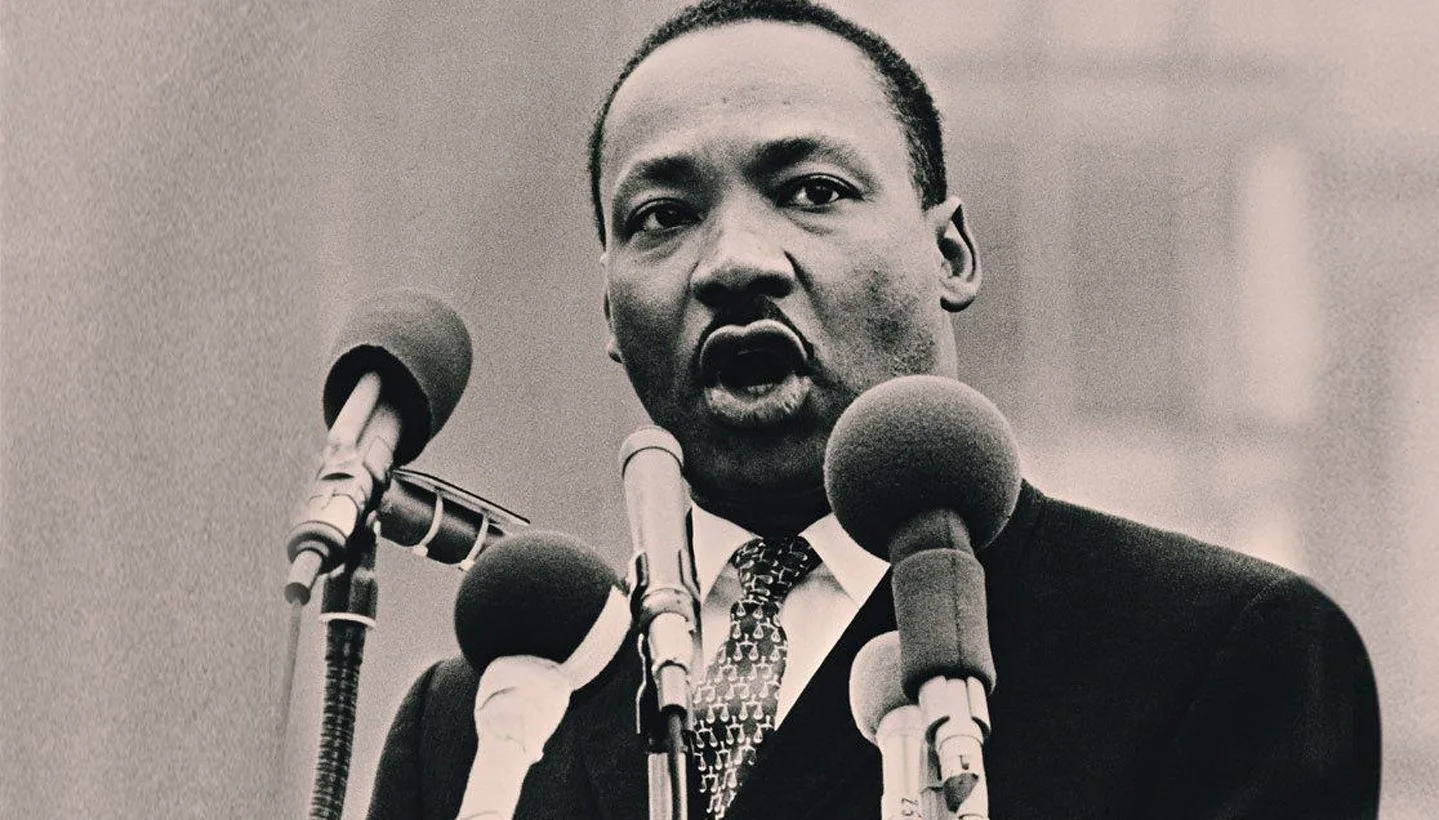

Martin Luther King made a case for the healing power of love following trauma when he so poignantly said: “I have decided to stick with love… Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

Read more in Daily Maverick: “Ruling elites are depriving African countries of innovation and dynamic leadership, and fuelling hopelessness”

Victims of colonial, apartheid and chronic poverty trauma frequently live for the now because no imaginable future appears possible. Short-termism often becomes the norm, as planning for the future appears fruitless. Societies emerging from trauma may fall into victimhood more easily – blaming former colonial powers (often rightly so), outsiders and internal enemies – rather than proactively building a new future.

Martin Luther King in New York on 10 September 1963. (Photo: Santi Visalli / Getty images)

Lack of agency: Impact on democracy and development

For countries emerging from colonialism, apartheid and civil conflict, the spread and deepening of democratic values and attitudes are crucial. To build democracy, post-colonial and post-apartheid societies must democratise governing regimes – the democratic nature of both formal and informal institutions – and democratise societies – the embeddedness of democratic norms, values and attitudes in the “culture’.

Lack of agency undermines these critical ingredients needed to deepen democracy.

But lack of agency also undermines development, as it blinds victims from seeing the opportunities within and around them. It blocks the imagination. It dashes hope. US writer Rebecca Solnit so convincingly argues in another context that hope does not mean denying difficult realities. It means “facing them and addressing them”, and acting on them.

“Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognise uncertainty, you recognise that you may be able to influence the outcomes – you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable.”

Undermining entrepreneurship

The lack of individual agency undermines building a culture of entrepreneurship. Since independence from colonialism, African industrialisation, development and growth have been stunted because of the failure to foster entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurs change society. They create new industries, new jobs and new wealth – which more people can benefit from. They increase the size of economies. They fuel economic growth. They inspire a virtual cycle of others trying their hand at starting new businesses, developments and initiatives too.

Researchers Robert Hirsch, Michael Peters and Dean Shepherd, in their book, Entrepreneurship, describe entrepreneurship’s role in economic development as involving “more than just increasing per capita output and income; it involves initiating and constituting change in the structure of business and society”.

(Photo: amazon.com)

The destruction of “familiar and trusted social benchmarks” that were there before colonialism and apartheid, combined with the processes of industrialisation, caused “dislocation” or “void”, whether cultural, individual or social, at the individual and communal level. The danger is that individuals often replace this “void” with religious, ethnic and cultural fundamentalism.

Democrats would want the void to be filled by new democratic values, mores and cultures – and by the best (most democratic) elements of cultural, religious and spiritual values. In the South African situation this “existential insecurity” has generated “illiberal attitudes” in the wider citizenry: violent crime, low level of tolerance for differences, xenophobia, social conservatism, and so on.

At the collective level it has led to tribalism, religious and ethnic nationalism, and xenophobia. Victims often choose parties and leaders who rage, who attack former oppressor power, communities and outsiders. Victims often vote for political movements from their own ethnic group or with whom they shared struggle history, even if these movements and leaders are corrupt, incompetent or act against the victims’ interests. They hand over their agency to these movements and their leaders.

Victims regularly vote against their own interests – trauma bond voting: therefore repeating cycles of voting for incompetence, corruption and for the continuation of poverty, which in turn reinforce the negative impact of colonialism and apartheid.

Many vote for “father” figures, for aggressive masculine figures who rage against the colonial or apartheid “enemy” or enemies from other groups and non-nationals. Victims often vote for parties and leaders with whom they share a “struggle” past, ethnicity and colour – rather than on competence, honesty and compassion.

This means that post-colonial African countries and post-apartheid South Africa appear to catapult a disproportionate number of psychopathic, narcissistic and mean-spirited leaders into power. Voting for such leaders and parties goes against the voters’ own interests, only further increasing their poverty, marginalisation and underdevelopment. This brings leaders who are corrupt, incompetent and uncaring – resulting in the continuation of poverty, which in turn reinforces the existential insecurity of the victims, and erodes their brittle agency further.

On the face of it then, it appears that African voters, who lack agency, appear to have trauma bonds, attachments based on repeated cycles of empty promises, blame-shifting and affirmations based on shared oppressive pasts, ethnicity or colour, with toxic, narcissistic and psychopathic leaders and governing parties – that lock voters into continuing to support these mean-spirited leaders and parties.

When post-apartheid and postcolonial movements fail, victims often also hand over their agency to non-political, fundamentalist movements, such as religious or personal addictions.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Furthermore, many of Africa and South Africa’s black political, business and social elite have responded to the “dislocation” by the obsessive pursuit of material possessions. In such cases, self-esteem, identity and individual value are increasingly measured in how much an individual possesses in material possessions. They adopt “bling” lifestyles of Beverly Hills-style mansions, foreign shopping and expensive cars, not only to fill the “void”, but also to show they are the “equals” of white colonialists and apartheid elite.

Post-colonial and post-apartheid responses to brokenness

Postcolonial and post-apartheid governments, governing parties and intellectuals have provided various, mostly inadequate responses to the existential insecurity. Leaders such as Zimbabwe’s late president Robert Mugabe have gone for hyper masculinity, attacking old enemies, such as former colonial powers and white business, and creating internal ones such as the opposition parties and ethnic communities different from theirs.

Read more in Daily Maverick: “The importance of uhuru, ubuntu and ujamaa in overcoming colonial trauma”

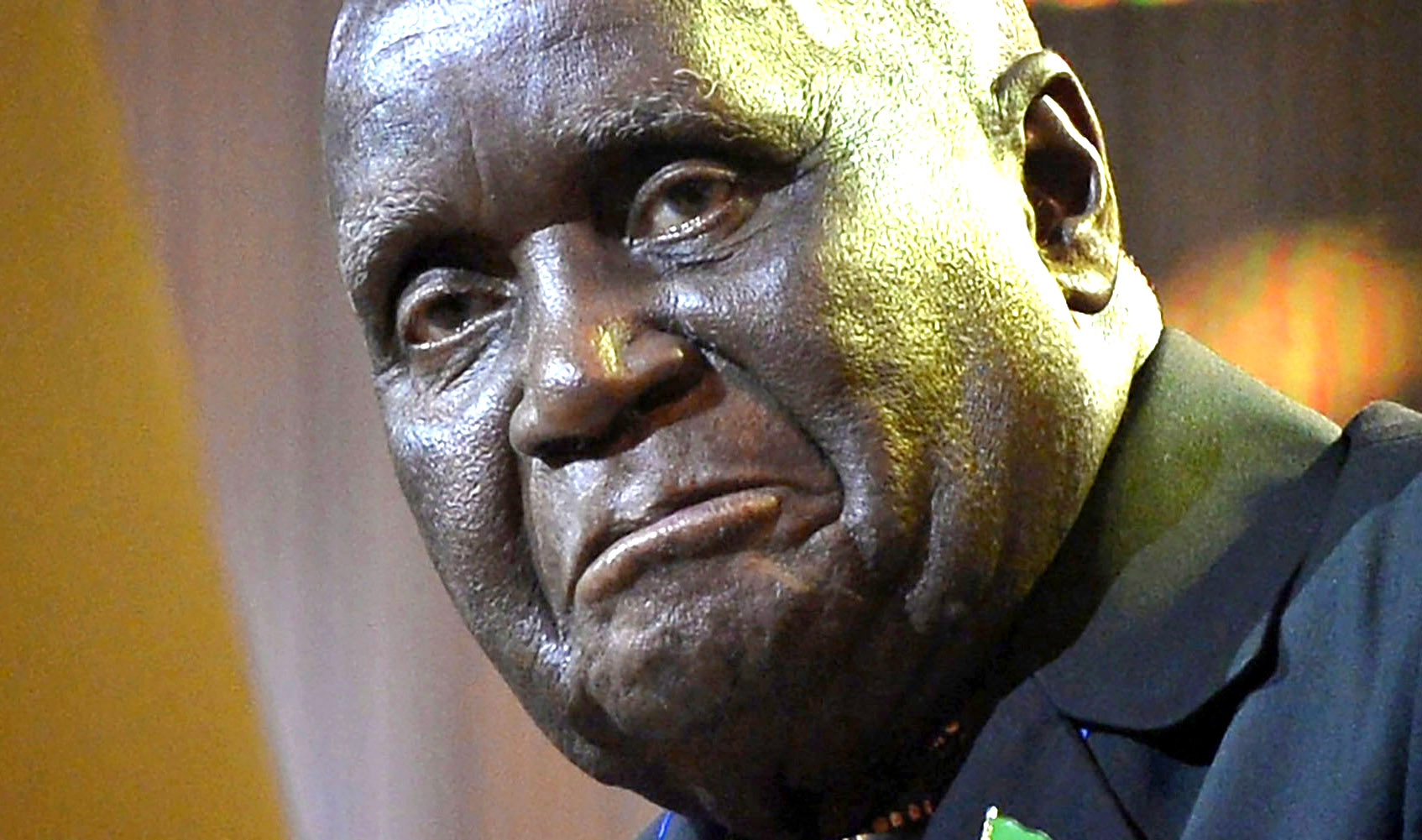

Some have tried to return to ancient African traditions – Kenneth Kaunda in his catastrophically failed experiment with African communalism, which left many to die of starvation, disrupted families and communities.

Former Zambian president Kenneth David Kaunda on 15 December 2013. (Photo: EPA / Odd Andersen / Pool)

Others have invented new African traditions or revived dead ones.

However, in all of these cases the resurrected African “traditions” and newly invented ones have undermined the basic human rights, dignity and equality of citizens.

However, by and large, most post-independence African governments and leaders – including in post-apartheid South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe have actively encouraged their supporters’ and voters’ lack of agency – as docile supporters would be loyal voters no matter their leaders’ and parties’ incompetence, corruption and indifference.

Clearly, many African leaders have turned out to be such disasters to their people because they lack love for their fellow human beings, whether their colour, ethnicity or religion.

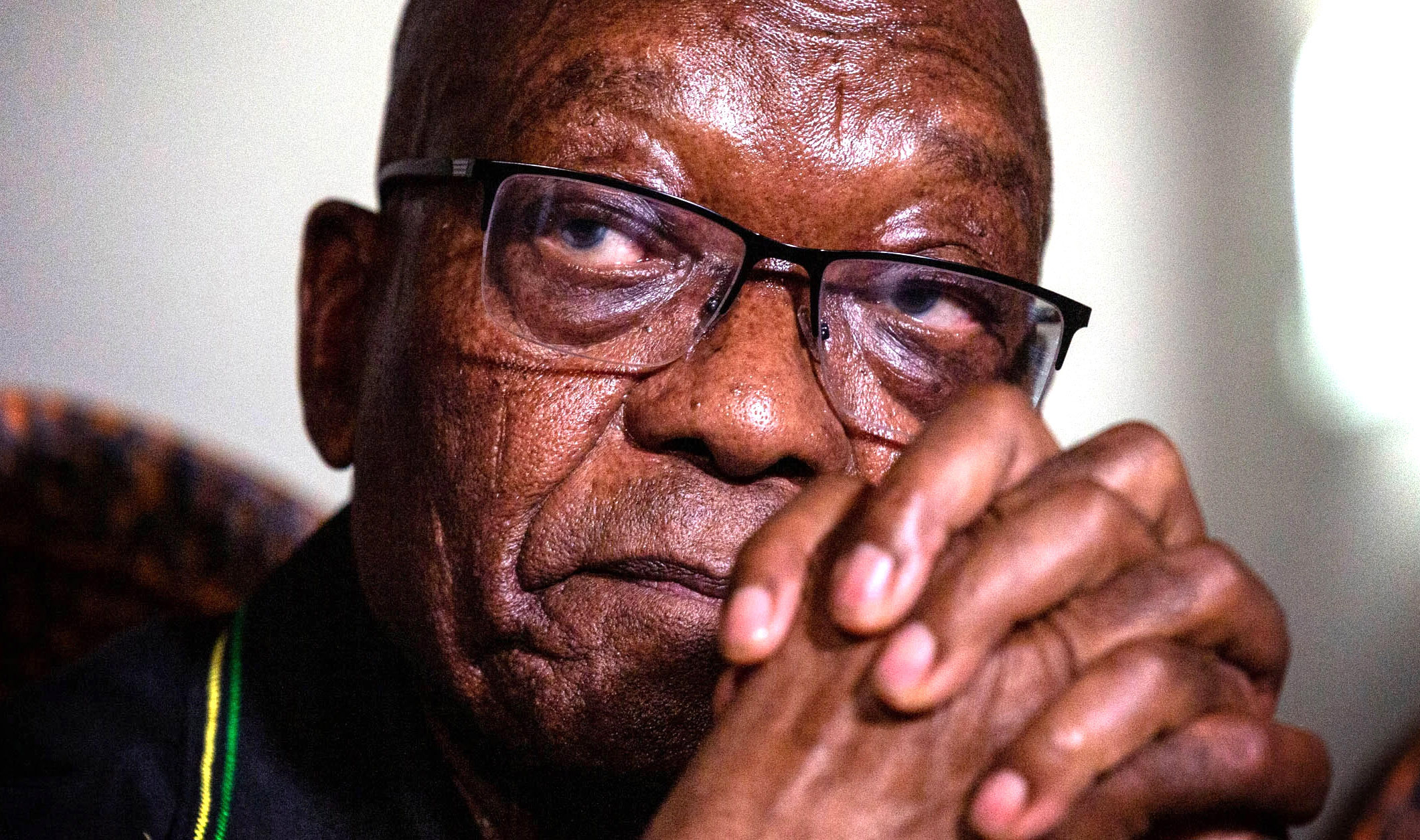

Many leaders such as former president Jacob Zuma, Mugabe or Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni, behind their pretend love for the “people”, appear to see other people, whether supporters or voters, as objects of control, how they can use them, or if they are opponents, how to destroy them with a smile.

The late Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe (Photo: Pascal Le Segretain / Getty Images)

South Africa’s Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement (BC) of the 1970s emphasised the need to deal with the consequences of the broken individual as a prerequisite for successful development. However, the heirs of the BC movement have not elaborated beyond the “black is beautiful” theme to provide a countermessage to black individual alienation caused by colonialism and apartheid.

Fostering a new sense of self, individual agency, and self-love

Fostering individual and collective agency will be crucial for individual and collective healing – and a prerequisite to build democracy, foster inclusive development and societal peace.

It is crucial that the post-apartheid state treat citizenship with dignity, care and efficiency.

Ultimately, reducing poverty and inequality and strengthening democracy in South Africa, which will help in reducing the “existential insecurity” of blacks and make the black majority “winners” also, is a core requirement of building a durable democracy, sustainable development and peaceful communities in South Africa.

Fostering sustainable development, quality democracies and relatively peaceful societies that emerged from violence, cannot happen without the former oppressed communities inculcating a mass culture of individual self-love, and consistently electing leaders who operate from love, who have compassion for others that stretches across ethnicity, colour, or region, and is not based on self-interest.

Changing long-held beliefs, perceptions and values – which undermines individual agency, are not easy. At the individual level, changing long-held beliefs and values is even more difficult when one’s beliefs are intertwined with one’s identity and one’s conception of self.

Given the reality of broken individuals, families and communities, self-love will have to be taught from nursery school to higher education institutions. Workplaces should also inculcate individual self-love among their staff. All other areas of human interaction – social, religious, cultural and political organisations – should include self-love, agency assertion and self-esteem, as part of their induction, training and wellness programmes.

Former president Jacob Zuma. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Yeshiel Panchia)

Anti-poverty strategies must be multidimensional in that it must include self-esteem, self-love and individual agency. Cultural, religious and communal practices that undermine individual agency, must be cut out.

We need a civil society movement to restore self-love, self-esteem and individual agency. Practices such as conscious breathing, meditation and volunteering are crucial tools to build self-love, self-esteem and agency that should be introduced more widely by civil organisations.

Finally, to break the cycle of poverty, underdevelopment and corruption, it is crucial that ordinary citizens must stop voting based on the past, based on struggle credentials and based on ethnic, colour and party solidarity, but vote on merit – for those who are honest, competent and compassionate, even if they do not share your colour, religion or past.

To foster individual and collective self-love, self-esteem and agency, South Africa and other African countries require leadership that has greater emotional maturity, is compassionate and emphasises forgiveness – leaders who exhibit love, who will have what Christine Hanna calls the “courage to do the right thing even when it is hard”. DM/MC

William Gumede is Executive Chairperson of the Democracy Works Foundation.

This is an extract from William Gumede’s keynote address to Breathwork Africa’s Umoya Breathfest at the Cradle Valley Guest House, Cradle of Humankind, 18 to 22 September 2022.

Comments - Please login in order to comment.