SOCIAL SECURITY OP-ED

Government needs to walk the talk on income support — and that means the whole of government

The noble commitment by President Cyril Ramaphosa on income support for adults faces multiple landmines. There are many actors in the state and among elites in society who will try to frustrate this goal for a variety of reasons which have mainly to do with vested interests and outdated economic dogma.

President Cyril Ramaphosa made an important statement on income support for adults in his 2022 State of the Nation Address (Sona) on 10 February 2022, and his reply to the Sona debate on 16 February.

In his Sona the president announced the extension of the Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant for a further year, saying that detailed technical work will be undertaken to decide the best income support options which would replace the grant, following discussions with civil society. He further stated that basic income should not come at the expense of public services, a view also advanced by civil society in their meeting with him.

In his reply to the Sona debate he stated that “we need to fill the gap in social protection to achieve a minimum level of support for those who cannot find work”, and that grants have provided “an effective system for income redistribution and poverty alleviation”.

He echoed the view of civil society that this was an immediate imperative, and that “given the scale of unemployment and the impact of the pandemic, the interventions we are undertaking to create jobs will take many years to reach all 11 million South Africans who are unemployed”.

Meanwhile “millions of South Africans face the immediate challenge of feeding themselves and their families”. He concluded that “finding a sustainable, affordable and effective solution must be one of the central pillars of the social compact we have undertaken to build”.

But this noble commitment by the president faces multiple landmines in the way of its realisation. As anyone who has been involved in this struggle for human dignity knows, there are many actors in the state, and among elites in society, who will try to frustrate this goal for a variety of reasons which have mainly to do with vested interests and outdated economic dogma.

Achieving this historic goal of basic income support for all who need it will require the president himself, together with allies in civil society, to champion an intervention which will make South Africa a global leader in social protection. Given the plethora of challenges on the president’s table, this will require sustained focus and pressure from civil society to ensure that the question of tackling hunger and poverty become the number one priority of this administration — just as president Lula (Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva) single-mindedly pursued the “zero hunger” strategy in Brazil.

This is doable but requires not only that civil society intensify its mobilisation on this question, but that the president himself makes income security a political priority and overrules those in government who would like to undermine and sabotage this objective.

There are a range of challenges that will require the president’s more active oversight and leadership if the transition to income support is to be a coherent one. At a high level, these fall into two broad categories:

- Challenges in extending and rolling out the SRD grant at a reasonable level, to all intended beneficiaries. There are practical, legal, and policy challenges; and

- Challenges in ensuring a seamless transition to a permanent form of income support, putting the necessary policy, systems, financing and legislation in place.

Resolving logistical challenges in extending and rolling out the SRD grant, and transitioning to permanent income support

The State of Disaster (SOD), under which the SRD grant is being implemented, is expected to be lifted from April 2022. This will therefore require the Department of Social Development (DSD) to finalise regulations in terms of the Social Assistance Act, to empower DSD and Sassa to administer the SRD grant.

While this should be relatively straightforward in theory, it requires Treasury concurrence before the regulations can be finalised. History shows us that Treasury has often (ab)used this power to frustrate policies they are unhappy with. It is therefore a concern that they may impose conditions aimed at minimising the numbers able to qualify for the grant. Such interference should not be accepted.

Secondly, there is not much time to finalise policy and legislation on permanent income support measures needed to replace the SRD grant. On the face of it, the decision to extend the SRD grant by one year gives a fair bit of time to decide on options to replace it. But in reality, given the need to process policy and legislation through a notoriously slow legislative process and to deal with changes to the Budget needed within the budget cycle, the major decisions need to be taken within the next few months, and by June or July at the latest. If this is not done, the danger is that again no policy will be in place when the SRD grant expires in March next year.

We have already seen the chaos caused by a stop-start policy of extending and suspending the grant — and its social impact including its contribution to the July 2021 looting in the context of social desperation. This is the worst-case scenario that must be avoided at all costs. But even without such dramatic social consequences, the uncertainty caused by the inability to engage in long-term planning is bad for policymakers, undermines effective implementation of basic income support or the development of the necessary systems, and causes anxiety and uncertainty amongst beneficiaries.

Addressing the negative impacts of attempts to minimise the level and reach of the SRD grant

While Treasury failed in its attempts to block the extension of the grant beyond March 2022, it appears they have successfully resisted increasing its level. Reports indicate that proposals from the Presidency to at least increase it to the Child Support grant level of R460 will not be taken forward, and there is not even an inflationary increase being proposed to the SRD grant. This means a real decline in the value of the SRD grant and a continuation of an arbitrary, pitifully low, amount (R350) for the grant which is not linked to any objective poverty measure.

Even if the SRD grant was not increased to the revised food poverty line (FPL) of R624 p/m, a significant step toward this would have been easily affordable without any tax increases given inter alia the large revenue overruns anticipated for this Budget, estimated by some to be over R200-billion above the 2021 Budget predictions (contrary to some assertions that the underlying commodities boom is a short term cyclical blip, various factors suggest that it is in fact a longer term, secular trend).

But given Treasury’s record, there is an expectation that much of this revenue surplus will go to debt reduction — i.e. putting precious resources into the financial markets rather than a stimulus into struggling local economies and desperate people’s pockets; while a miserly R44-billion is allocated to the SRD grants which an estimated half the population are dependent on (10.5 million beneficiaries with at least two dependents each = over 30 million South Africans).

It is also expected that, given past experience, Treasury’s allocation and bureaucratic requirements will put pressure on DSD and Sassa to cap the number of SRD grant beneficiaries at current levels (around 10.5 million beneficiaries). The push to suppress the level of the grant, and contain beneficiaries at current numbers, will be a huge missed opportunity to address poverty and hunger and inject a serious stimulus into our depressed economy — which surely must be the national priority at this point?

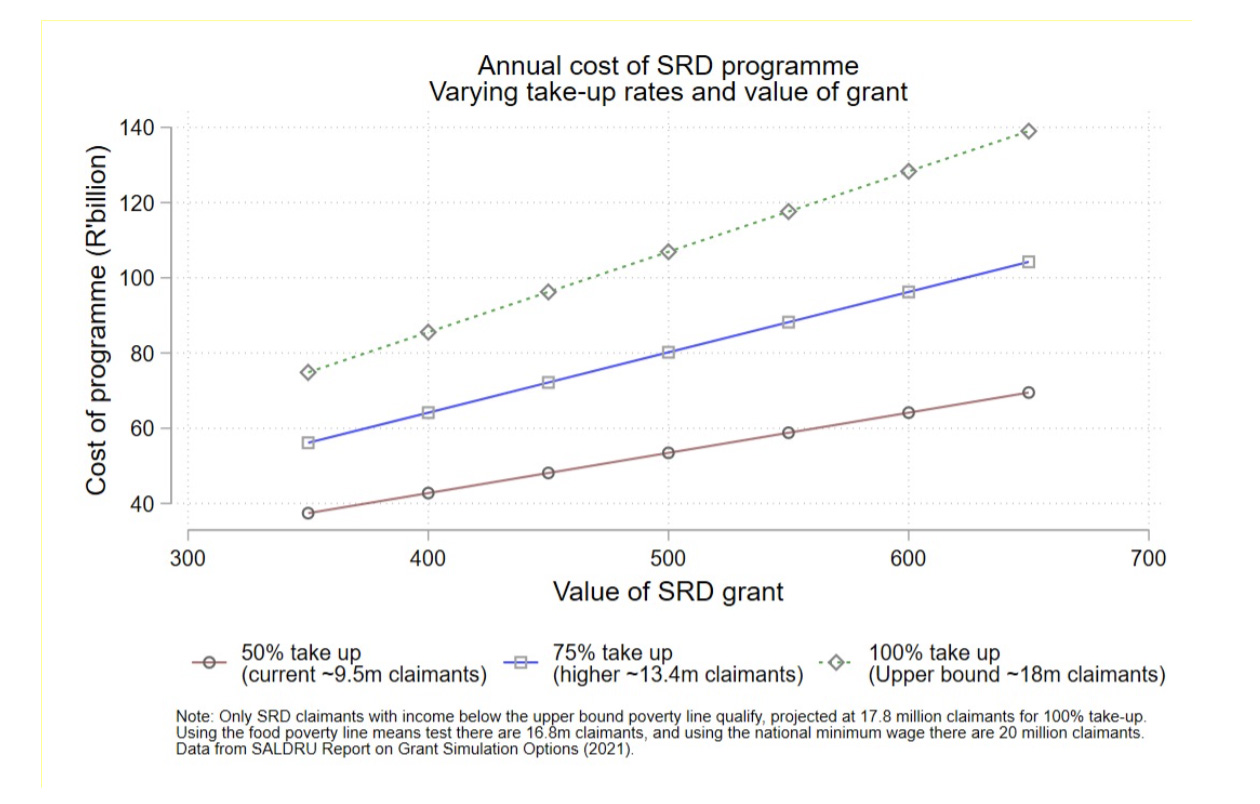

For demonstration purposes, the graph below shows that increasing the number of beneficiaries at a significantly improved grant level of say R500p/m would be affordable within the existing envelope, even with a more generous means test*: the cost of extending the grant to 13.4 million people (or 75% of potential beneficiaries) at R500p/m would be R80-billion per annum, less than half of the tax overruns. In reality, DSD is unlikely to be able to register the additional three million beneficiaries suggested in this scenario, so the real number is likely to be significantly less than this.

*Note: eligibility for the grant in the calculation below is based on applicants’ income being below the upper-bound poverty line, as opposed to the current means test which requires applicants to have income below the food poverty line.

(Table: by Ihsaan Bassier)

As much as the rollout of the SRD grant is an impressive achievement, it is riddled with multiple problems, which unfairly exclude many potential beneficiaries. So any attempt to cap the level of beneficiaries at current levels would both be grossly unfair, and probably unlawful.

The latest official figures from Sassa show that there were 15.15 million applicants as at 1 February 2022, of which 10.45 million were approved. In other words, around 4.7 million applications (or just under one third) were turned down, many of these on the basis of faulty PAYE and UIF databases, and therefore could be subject to court challenge. Civil society in its meeting with the president last month proposed a multi-stakeholder task team to deal with these and other issues. This needs to be taken forward.

We need an honest discussion on financing options

We keep on hearing dire threats from the financial press and conservative economists of the inevitability of substantial VAT and personal income tax (PIT) bracket increases if a basic income is introduced. Some claim that even the extension of the current R350 grant will require this, ignoring the realities of our current fiscal position.

While this is clearly fear-mongering, there will in reality need to be tax changes in the medium term if permanent income support at a reasonable level is to be introduced. This should not necessarily be seen as a bad thing. Dedicated tax changes which are directed into such a socially needed and economically constructive investment should be embraced by most South Africans if the value of this is properly appreciated (in contrast to the popular perception that taxes are being siphoned off for illegitimate purposes, many people appreciate that dedicated taxes going directly to the poor would be a legitimate and constructive contribution).

Current discourse in the financial media, and among mainstream economists, seems to deliberately ignore the fact that a range of creative financing alternatives have been advanced by the Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) and other organisations beyond the narrow options of VAT and PIT, and have been rigorously costed and assessed — although further work is needed on how these options can best be prioritised and sequenced.

Contrary to the fear-mongering claim by some commentators that ordinary workers will have to forego income to finance a permanent grant, and that the taxes will have a whole host of unintended consequences, these financing options present a whole menu of possibilities that can be tailored to the objectives which such a policy aims to achieve.

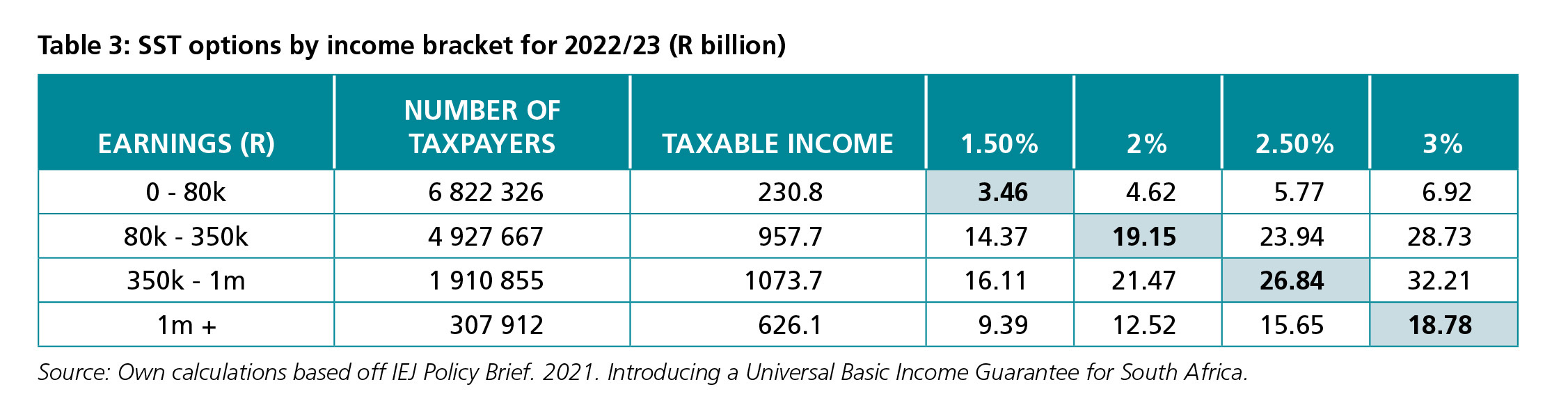

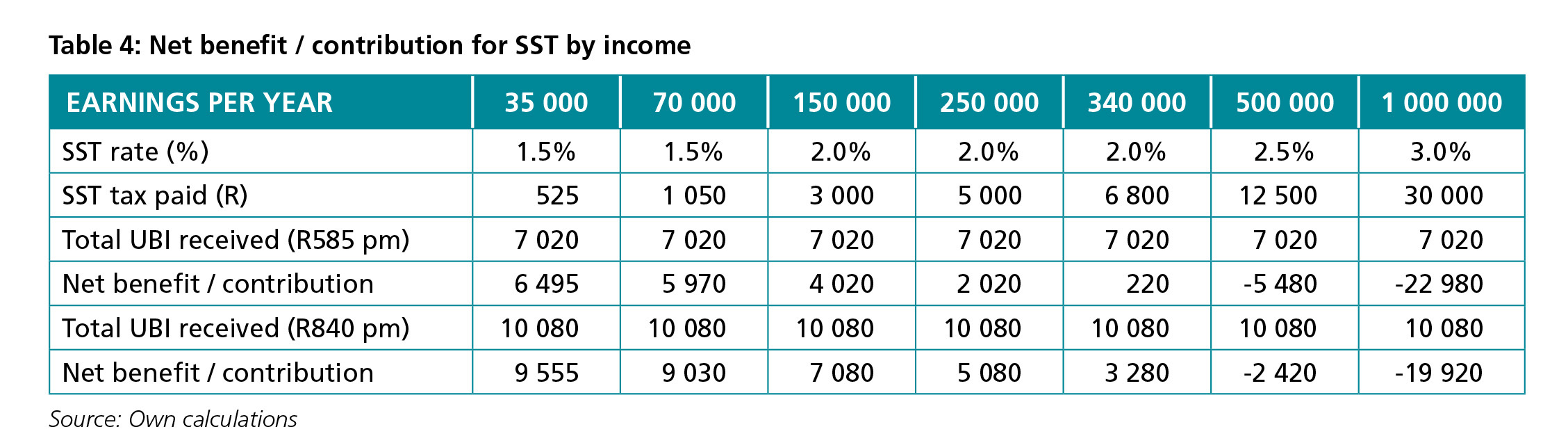

So if for example, we desire to provide income support to all those living in poverty, then a basic income should be extended both to the unemployed and those forming part of the working poor. A dedicated instrument such as a social security tax would ensure that while all earners contribute, low-income earners would receive a net benefit and only higher-income earners would make a net contribution. The tables below, extracted from the IEJ Financing Brief, demonstrate an example of how this could work:

In addition, the IEJ brief proposes other financing options for consideration that are not related to PIT or VAT, such as a financial transactions tax and a resource rent tax. These and other financing options should be seriously considered.

Treasury should not be determining social security policy

The record of National Treasury in the social security policy space over the last two decades has been destructive and problematic, both when they have been part of formulating policy and when they have responded to policy formulated by the relevant players. They have abused their control of the public purse to effectively veto policy choices in an area where they lack the necessary expertise.

The destructive record of Treasury on social protection issues goes back to at least the 2003 Taylor Committee which proposed the introduction of a Basic Income grant. This was openly opposed and blocked by Treasury despite it not having a mandate to determine social policy questions.

A number of years later, it blocked a policy document on social security reform by the DSD, leading to Cabinet mandating a joint DSD/ Treasury process on social security and retirement reform. Treasury effectively frustrated this process for over a decade, both in government and then in Nedlac (including through trying to unilaterally drive through retirement reform while blocking social security reform). Ultimately this frustration led to DSD publishing a Green Paper which was the outcome of the joint NT/DSD deliberations, as well as deliberations in Nedlac. It is now well known that despite NT having been part of this process, they forced the withdrawal of the Green Paper.

More recently, we have seen how Treasury’s clumsy and misguided attempts to engage with policy issues around Basic Income has ended in tears. Their attempt to drive the ill-thought-through household or family grant proposal was mainly motivated by attempts to block extension of the SRD grant, and the eventual adoption of a Basic Income grant.

Treasury’s engagement in social policy (both on social security and other issues) has consistently had one thing in common: it has been determined purely by conservative fiscally driven considerations, with little or no regard for the social and economic realities which the policies are trying to address; and have been characterised by closed-door technocratic processes.

The fact that Treasury’s household or family grant proposal was buried by sustained civil society opposition should not be interpreted as meaning that Treasury has ended its meddling in the social security policy process. They will continue to find ingenious and devious ways to block the realisation of a meaningful income support system if they are given the space to do so.

We can therefore expect further attempts to hollow out, or frustrate, any progress on instituting income support for the poor in South Africa. Some of these which have already been floated or signalled in various ways include: proposals for a narrow “work seekers grant” which is only extended to those “actively seeking work” along the lines of the unworkable World Bank proposal; restructuring of the social grants system so that existing grants are collapsed into one new grant (thereby disadvantaging targeted groups such as the aged, disabled, children) etc — or any other option which reduces expenditure on grants.

These proposals are all fundamentally problematic or unworkable, but if given the space will nonetheless be ruthlessly advanced by Treasury’s technocratic machinery.

In the Sona and his reply to the Sona debate, the president has indicated that this time will be used to undertake “detailed technical work” on options to replace the SRD grant. Civil society in its meeting with the president in January proposed the idea of a Presidential Panel to assess the abundant research and evidence, and within tight time frames, make a set of recommendations on implementation of Basic Income.

The process needs to be open and transparent, driven by those with relevant expertise, together with civil society organisations working closely on issues of the grant and the role of Treasury tightly circumscribed. Then we have the possibility of making a historic breakthrough that will change the lives of over half our population. DM

Neil Coleman is Co-Founder and Senior Policy Specialist at the Institute for Economic Justice. This article is written in his personal capacity. Twitter: @NeilColemanSA

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9193″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

South Africa has been bankrupted so the foreign economic interests can profit !

Consider the case of Medupi The initial expected cost of R80 billion (2007 Rands), was revised to R154 billion (2013 Rands). 2019, the cost of Medupi was independently estimated at R234 billion. (2019 Rands)

There was widespread corruption on the project by Hitachi – which in 2015 was prosecuted and fined US$19 million under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act for bribing South Africa’s ruling party– and many other contractors. This was all well known by World Bank President Robert Zoellick, who nevertheless arranged his institution’s largest-ever project loan for Medupi: US$3.75 billion. In 2005 Eskom contracted Black & Veatch to manage the construction of Kusile, situated in Mpumalanga, for R100 million. By the end of December 2017 and after changing the contract and amending the scope of the job six times the power utility had paid the US firm a total of R14.9 billion.

Why South Africans not protesting by the HQ of these companies ? Politicans and the mass media have been corrupted so indoctrinate the people to blame everyone except the crooks who caused the mess !