RISE UP AGAINST GRAFT OP-ED

Murphy Morobe: The fight against corruption is a fight for the survival of our democracy

The fight against corruption may seem to be more against the pecuniary aspects of that corruption – people stealing money from the state – but it is at heart a fundamental threat to the constitutional democracy for which Murphy Morobe and many others suffered imprisonment and torture.

Murphy Morobe can draw a line between the day on 16 June 1976 when he walked out of Morris Isaacson High School in Soweto to join the protests against the enforcement of Afrikaans as a language of instruction in African schools, and his determination to fight corruption today.

The contexts, of course, were entirely different. Then, as one of the key organisers of the June 16 protests, Morobe went into hiding immediately after the uprising. But his luck, as he puts it, ran out on the last day of December that year. He was one of three activists the police wanted as state witnesses in the trial of Joe Gqabi and others, known as the Pretoria 12. He refused, as did his comrades, and they were sentenced to six months’ hard labour in Leeuwkop. When he emerged from prison he was immediately charged for being one of the leaders of the 1976 uprising.

After a trial that lasted almost a year he was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment, four suspended, and spent the remaining three on Robben Island. For Morobe the point was this: “I’ve always understood we were fighting a corrupt system… it was a corruption of the political system, it was corruption of the administrative system in the way in which it dispensed administrative injustice against black people primarily and (it was) the corruption of the human condition across all levels of our existence.”

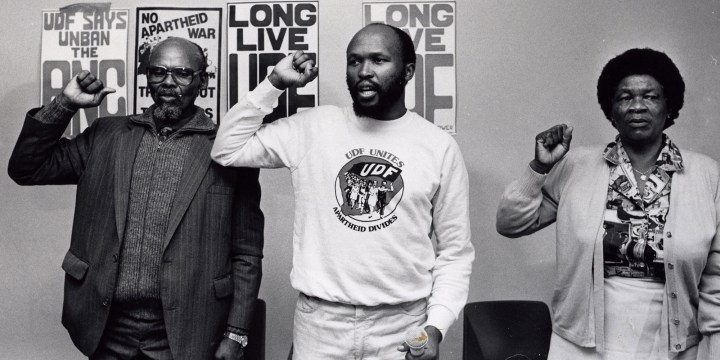

African National Congress stalwart Murphy Morobe during a media briefing by the ANC veterans at the Constitution Hill ahead of the party’s national policy conference on June 29, 2017 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sowetan / Thulani Mbele)

Today one of the main convenors of the Defend Our Democracy campaign, Morobe spoke to me on the eve of a nationwide campaign against corruption in South Africa. Led by the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation, several organisations ranging from legal bodies to faith organisations and business lobbies, have endorsed the campaign, which culminates on International Human Rights Day, 10 December.

“As South Africa emerges from a local government election in which many citizens chose not to vote, there is a need to re-engage the public around participatory democracy, holding public representatives accountable and playing an active role in advocating for clean and ethical governance,” said the organisations in a statement.

In some senses, the broad coalition echoes the formation of the United Democratic Front in 1983, of which Morobe was a senior official. He had come off the island the year before and joined the trade union movement – the General and Allied Workers Union – led by such activists as Sydney Mufamadi, now President Cyril Ramaphosa’s national security adviser, and Amos Masondo, now chair of the National Council of Provinces – to fight, as he put it, “corruption in the industrial sector”, and for the voices of African workers to be heard.

Then, a host of organisations ranging from churches to trade unions to civic associations joined forces to fight apartheid. It was a fight against “the corruption and corrosion of society across all spheres of life”, a system he believes was in place long before 1948: “The British have a lot to tell us about their own role in bringing about apartheid in this country” – stretching back to how early settlers robbed indigenous people of their cattle “for trinkets”, to land conquests and eventually the Land Act, “one of those ultimate acts of political corruption, which deprived people of the right to be in the land of their birth”.

Today, the fight may seem to be more against the pecuniary aspects of corruption – people stealing money from the state – but it is a fundamental threat to the constitutional democracy for which Morobe and many others suffered imprisonment and torture. “Because corruption can be as broad or narrow as you want it to be, but it all depends on a set of principles that you set up to live your life.”

And if those principles are short-circuited by “selfish, self-aggrandising behaviour” it undermines the basic principle that “every society should be built around: sincerity, honesty, humility, and trust.”

Even in the UDF, where he and others saw these principles breached in its own ranks, he spoke out. The difficult task of condemning the activities of the nefarious Mandela United Football Club that had coalesced around Winnie Mandela, the wife of the jailed ANC leader, Nelson Mandela, fell to Morobe as publicity secretary in 1989. He had just emerged from another long period of detention under the State of Emergency – and a dramatic escape with fellow detainees Valli Moosa and Vusi Khanyile when they holed up in the US Consulate for several months – when they first heard rumours of the “football team running rampant” in Soweto. “It was clear that if we did not do something soon, the integrity of the movement was going to be completely denuded, so that’s really what drove us rather than a like or dislike of any individual. It was principle and policy positions.”

He may have recognised the discomfort of acting against one’s own when, as head of communications in the Presidency, he became aware of the matter involving Schabir Shaik and then deputy president Jacob Zuma. “I always sought to find ways of understanding that phenomenon at the time. And I think I even had a more benign interpretation… understanding lapses in judgement in the way that relationship had evolved. And we were not even talking the Guptas at that time.”

From the early days of the ANC government, “there would always be people around with money who would want to circle around people of influence for whatever reasons. And some of the initial assistances would have probably seemed benign at face value, not knowing what their ultimate intention was.”

But the Shaik affair was different. It involved a series of payments from Shaik’s holding company and the French arms dealer, Thales, to Zuma, allegedly for preferential treatment in the deal to re-equip the South African National Defence Force negotiated first under the Mandela and then the Mbeki governments. Zuma was MEC for economic affairs in KwaZulu-Natal at the time and later deputy president of the country.

Morobe says now it was clear “there were vultures that were circulating around the ANC” but that those in leadership positions should have been “guardians of the organisation”.

However, the Shaik-Zuma case had a deeply divisive impact on the ANC “to such an extent that even the NEC itself, the highest decision-making body outside conference, seemed to have been rendered ineffectual in terms of making the kinds of interventions that we had been accustomed to from the ANC”. There was a sense that the organisation had been infiltrated by something “debilitating, that made it unable to make those serious, ethical, principle-based decisions”.

After the ANC’s Polokwane conference and Zuma’s election as president, he believes a systematic undermining of state institutions began. Only the judiciary was left relatively untouched, although there have been serious attempts to discredit it from a faction within the ANC.

The incapacity of the state became clear during the failed July insurrection, ostensibly a reaction to the jailing of Zuma by the Constitutional Court for his refusal to obey a summons to testify at the Commission of Inquiry into State Capture. The extent of the violence, especially in KZN, says Morobe, was shocking but much more so was “the extent to which our security forces were missing in action”.

Although some have identified poverty and unemployment as driving factors, Morobe argues the key causes were essentially political, with one central figure around whom the organisers of the insurrection coalesced. “Some of the people driving this were not poor; they were well-heeled individuals who had political connections.” Many “lived on the internet” and became part of a social media campaign to incite the violence.

The apparently well-orchestrated mission to destroy the N3 on the Sunday evening before the looting of the malls was one sign. “These were people… supporting their man in Nkandla – but they were hiding behind ordinary people’s plight; that’s the cowardice of it all. They would not show their faces.”

Professor Qurraisha Abdool Karim, the KZN-based but world-renowned epidemiologist, gave a vivid description of precisely how incapacitated or unwilling the police were to stop the destruction of infrastructure. Speaking in the immediate aftermath of the uprising, she told a Defend Our Democracy briefing of how healthcare workers had been stuck on their shifts for days, unable to be replaced by new staff because of the disruption of transport, of how trauma and burn injury admissions had increased sharply, and importantly, of how the vaccination programme had been disrupted. But the most pressing concern was the damaging of oxygen supplies and the burning down of two pharmaceutical warehouses that stored, among other things, Covid-19 vaccines.

“Right now, there are long lines and hours that citizens are waiting to secure basics – basics for their children, basics for their babies. And, yes, the looting continues, and we have a visible absence of law enforcement agencies, and an absence of the military in Durban.”

All of this, she said, because of “self-interested politicians protecting themselves”.

Later, she told the Sunday Times that the average daily number of Covid-19 cases in the province had increased from 632 to 1,665 in the aftermath of the unrest.

For Morobe, the absence of law enforcement agencies was a sign of how severely institutions had been damaged under the Zuma administration.

Did the ANC’s elective conference in Nasrec, which ultimately saw Cyril Ramaphosa being sworn in as president, give him hope?

Ramaphosa’s capacity, he says, is dependent on the people around him, and that group still reflects the deep divisions within the ANC. “We put a lot of store in Nasrec, but it was clear to us that it was not going to be just Nasrec alone. Those of us who were activists in the movement and in the country had to find a way of continuing to deepen activity.”

The battle against corruption is far from over. He notes how the proposed new infrastructure programme, as well as Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana’s economic rebuild programme offer new opportunities for malfeasance. “We know that there has been no effective undercutting of corrupt intent across the system.” While there have been some arrests, the “bigwigs” behind systemic corruption remain at large.

“So, there’s no doubt in my mind that they’ll be looking at these opportunities, these plans and programmes. Because they are not driven by the greater good. They are driven purely by the need to be in a position where they can extract as much as they can from what the state has to put out there.”

The results of the local government elections show that the ANC has a “limited window” to deal with corruption. Many people did not vote because they were reluctant to support the opposition, but could not vote for the ANC unless it came up with a “better-looking frock”. But the ANC couldn’t find a better dress.

Those elections also showed the destructive effects of corruption on almost every aspect of municipal service – from water to roads maintenance.

The purpose of the Anti-Corruption Week, he says, is to keep a “foot on the pedal” of the campaign against corruption.

The ANC has a “very limited window” before the national elections. “They must stop bullshitting us about introspection… When you get people who are accused of corrupt activities to become arbiters of who should become mayors of new towns, it tells me there is something wrong – still wrong – in the echelons of the senior ANC.”

Corruption endangers the essence of democracy itself. “Unless ordinary people see some consequence for corruption they may well not vote again in (national) elections.” DM

Anti-Corruption Week runs from 3 to 10 December. Information about the campaign can be found on www.defendourdemocracy.co.za

Pippa Green edits Econ3x3, an online publication based at UCT, and is on the advisory council of Defend Our Democracy.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a cosmetic piece of political choreography – Morobe needs to come clean with what he knows.

The ANC is responsible for the corruption and for turning a blind eye to it. so they can’t ” fix it.” I respect Mr Morobe – but the deep moral corruption in the ANC should force him to give up his membership in protest.

The ANC has a “very limited window” before the national elections. “They must stop bullsh***ing us about introspection… When you get people who are accused of corrupt activities to become arbiters of who should become mayors of new towns, it tells me there is something wrong – still wrong – in the echelons of the senior ANC.” Well said but Sir what do you know that you are not telling us?