Maverick Citizen OP-ED

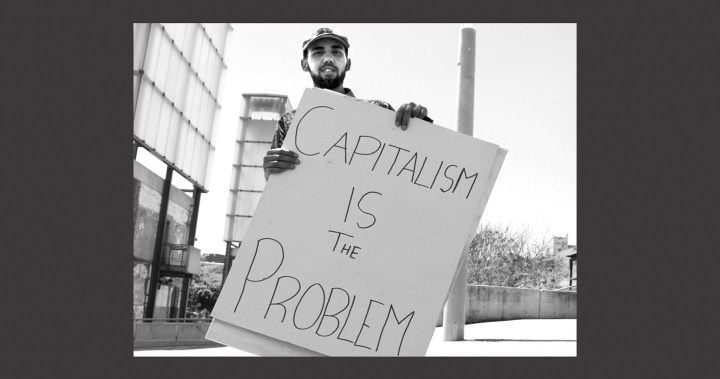

Greedy capitalist and carbon-criminal states need to feel the heat of climate justice

The notion that the climate crisis is a ‘human’ problem is too general, too broad and ultimately misguided. This existential threat presented to our species has been manufactured by a small fraction of our species, in whose hands power and wealth is concentrated.

On Valentine’s Day 1990, the Voyager 1 spacecraft turned its eye upon our terrestrial home to snap a photograph from billions of kilometres away, before it eventually left the solar system. The iconic photo captured our world, what astronomer Carl Sagan famously called our “Pale Blue Dot”, for all its fragility.

Sagan described the precarity and isolation of our collective global circumstance in his famed, moving meditation on the photograph four years later.

“The Earth,” he wrote, “is a lonely speck in the great, enveloping cosmic dark.” A pixel under the protection of a species plagued by fractures, inequalities and unjust social hierarchies. In the Pale Blue Dot meditation, Sagan addresses the matter of humanity becoming a threat to humanity and notes a daunting reality:

“In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.”

With the exception of the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the climate crisis presents an unprecedented existential threat to humanity. However, the notion that the climate crisis is a “human” problem is too general, too broad and ultimately misguided. This existential threat presented to our species has been manufactured by a small fraction of our species, in whose hands power and wealth is concentrated.

In defining our resistance to this crisis, particularly in countries that have experienced the crime of colonialism, it is important for us to embed our existing decolonial discourses – especially those surrounding our generational mission – within the context of the climate crisis, which does not exist separately from the broader projects of colonisation and imperial domination. In articulating a revolutionary programme to define a post-capitalist era, our politics must be lucid to the reality that our socialism must necessarily be an international, intersectional eco-socialism for the masses, if we are to meet the material and political realities of our historical moment.

It is important for us to first acknowledge that the fire raging beneath our burning planet was lit and is fed by a global nexus of capital and carbon criminal states.

At the forthcoming Working Class Summit (WCS), hosted by the South African Federation of Trade Unions, a key step towards uniting working-class formations across the country, a climate crisis paper is being presented to assist in articulating a common programme.

In the climate crisis paper, which I have been involved with drafting, along with others including Alex Lenferna and Francina Nkosi, we argue that the climate crisis is, at its core, a crisis of capitalism, produced and reproduced by its logic. A logic of indefinite economic growth, which converts the commons into “natural capital” and greedily pursues the accumulation of Capital ad infinitum, pillaging the poorest in the global village and poisoning the planet in the process. This within a global landscape shaped by histories of patriarchy, imperial domination and colonisation. A global landscape governed by neoliberal capitalism, acting through the apparatus of multinational corporations.

Any analysis of the climate crisis that omits these structures of power and domination is an analysis of a burning planet that is not our own.

Our ‘Pale Blue Dot’: The pixel that is our planet, captured in all its fragility by the Voyager 1 spacecraft on 14 February 1990. The system of capitalism is a dangerous threat to this terrestrial home and the continued existence of our species. (Photo: NASA/JPL)

The warming of our planet will not impact all equally.

Geographically, certain areas will warm faster – southern Africa, for example, is warming at about two times the global average. Ours is a carbon criminal state – South Africa is the 12th-largest emitter of greenhouse gasses globally. Among these carbon criminal entities are the imperial and colonial states that are in league with global capital and that are to blame, overwhelmingly, for the crisis.

Yet it is the working classes and the most marginalised, particularly in the tri-continental of Africa, Asia and Latin America, who will bear the brunt of the climate crisis, while simultaneously being exploited by precisely the logic that produces that crisis. Imperialism must always be factored into our analysis – one of the largest carbon footprints in human history is left behind by the trampling boot of the US military.

Social injustices – unjust hierarchies of gender, sexuality, race and caste – are also reproduced and heightened by the climate crisis. The draft WCS Climate Crisis recognises that “women are typically the most impacted by ecological damage due to the sorts of work and labour they undertake and their relatively marginalised position in society”.

Similar sentiments can be expressed concerning those marginalised on account of race, sexuality and caste. As argued in a piece for Maverick Citizen on the challenges of building an intersectional justice movement, written by a host of young activists from The Collective Movement, “Justice must be addressed in its totality”. It is hence necessary for us to recognise the convergences in our battles against climate change, global capitalism and interlocking social injustices.

As student activists, our activisms must be informed by the reality that our institutions of learning do not exist separately from the Earth upon which they stand, or the nexus of capital and the carbon criminal state which governs every facet of our society.

The national priorities of the capitalist ANC state, warped by the interests of the corporate class, are made clear on the “bailout question” raised earlier in 2021 by the student movement against financial exclusion. The state refuses to bail out student debt, which the South African Union of Students quantified at about R13-billion nationally earlier in the year, yet it grants bailouts to failing fossil-fuel state-owned enterprises like SAA (more than R10-billion in 2020) and Eskom, where the total 2020 bailout exceeded R100-billion. This question of national priorities illustrates how our fight for free, quality, decolonised education does not exist separately from the struggle for climate justice.

The global colonial project of dispossession and dehumanisation, along with imperial wars, has seared wounds across a planet that is heating at a rapid pace. The #FeesMustFall movement, along with the #RhodesMustFall movement at UCT which preceded it earlier in 2015, were both inherently decolonial, as is the Climate Justice Charter, which champions decoloniality as a principle for Deep Just Transitions.

Our decolonial discourses surrounding free education must hence be embedded within the material realities of the climate crisis. Climate justice must rapidly become a core feature of our student politics, if we are to fulfil the decolonial mission of our generation, which extends beyond free education. The same insistence for radical structural change and the critical eye which we directed towards the question of higher education must now begin to look upon the entirety of the society which built that education system.

Wits University

At Wits University, where I have been a student activist since 2015, an appeal has repeatedly been made to the institution to divest from fossil fuels, including in a memorandum that was handed over to the institution on 21 September 2021, when the Climate Justice Charter was presented for adoption. Adoption of the charter, with its explicit opposition to extractivism, as a means to guide policy at the university would necessitate more than a divestment from fossil fuels, but a de-linking from mining capital.

At Wits, the institution is choosing to deepen those links, with a new 10-year, R52-million memorandum of understanding recently being signed with Sibanye-Stillwater, of which the murderous corporation Lonmin became a subsidiary in 2019. This in a context where Sibanye has neglected to pay any compensation to the widows and orphans of Marikana. A context where miners, who continue to live and work in dire and dangerous conditions, are still systematically exploited. The memory of Marikana is being desecrated by Wits University management, which is entrenching the historical relationship between the institution and the capitalist mining industry. Especially given that our generation has inherited a climate crisis, the question of the mines cannot be ignored by the student movement.

One cannot speak about the destruction of communities, the climate and the commons on the African continent without speaking about the blood-soaked mining industry, driven by the capitalist ideology of extractivism. Acting through mining corporations – particularly neoliberal, neocolonial corporations protected by capitalist states – this ideology has motivated countless crimes on the continent.

Extractivism is the addiction of the ruling class, poisoning our water and releasing toxic acid mine drainage, along with radioactive pollutants. When community activists stand up and say no to this degradation and destruction of their land, they are targeted. Fikile Ntshangase opposed Tendele Coal’s extension of the Somkhele coal mine in northern KwaZulu-Natal. On the evening of 22 October 2020, four gunmen barged into her home and murdered her in cold blood, in front of her 11-year-old grandson.

Our state is mired in this brutal industry. The unholy alliance between the ANC government and mining capital converges in the figure of Gwede Mantashe and the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy that he heads, which places the interests of corporations above the rights of communities to prior, informed consent concerning issues that affect their land and their lives.

Within the mining sector naked exploitation is rife. Miners are not paid a just, liveable wage and are denied adequate housing and basic benefits such as medical aid. Given these conditions, it is unsurprising that miners reach a point where there is collective recognition of what Assata Shakur of the Black Panther Party reminded us: “Nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them.” You have to force them.

So, miners down their tools and withhold the labour that creates the value which is swallowed by the capitalist class. They rise up in protest and strike to force the hand of mining capital. In response, capital calls upon the state to deploy its armed foot soldiers – a trigger-happy, bloodthirsty police force – to crush the resistance of workers in revolt, who are criminalised for merely exercising their right to go on strike.

The brutality of the police force called upon by Lonmin executives and deployed by the ANC state – the same SAPS that murdered Mthokozisi Ntumba in cold blood during 2021’s financial exclusion protests – culminated in the Marikana Massacre of 2012. The corpses of 34 miners were left to hang upon the conscience of the ANC. In the wake of the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, the ANC resolved to take up arms and Umkhonto weSizwe was formed. In the years following the Marikana Massacre, the ANC elevated a former Lonmin executive, once a union leader, to the office of the Presidency. As if it wasn’t clear enough already, the ruling party reminded us that it is most certainly no longer a liberation movement.

Following the dismissal of 30,000 mineworkers by Anglo American during a 1987 strike, Cyril Ramaphosa, then general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), said of the ruling class: “There is no such thing as a liberal bourgeois. They are all the same. They use fascist methods to destroy workers’ lives.”

While there is a distinction to be made between white capital and the emergent black bourgeoisie like Ramaphosa, deployed by the ANC to wage a farcical struggle in boardrooms within the capitalist class against white capital, Cyril’s words ring true insofar as this black bourgeoisie is indistinguishable from white capital in its response to a threat from below. Cyril’s appeal for “concomitant action” against the “dastardly criminals” at Marikana – an appeal for violence and brutality against the black working class rising up to claim the right to dignity – is so dehumanising that it may as well have come from a racist white capitalist. Fascist methods deployed by the new liberal elite are cloaked in a veneer of civility, but are no less fascist, no less despicable, no less deadly and destructive. If anything, it is made worse by the shocking betrayal of the working class embodied within the former general secretary of NUM. We must never look upon the “father figure at our family meetings” without noticing the bloodstains on his treacherous hands.

What, then, is to be done with the mines?

They have been the hotbed of economic exploitation for the entirety of their existence and are hence the bedrock of an economy produced through that exploitation. It is not enough to merely nationalise the mines and the commanding heights of the economy if that means wealth and power will be transferred and concentrated in the hands of the political elite. Nationalisation under a socialist state necessitates ownership and control of the mines be transferred to workers and affected communities. Decisions must be made democratically by those whose lives are most impacted by the mines in defining the Deep Just Transition away from mining capital.

Community organisations like Mining Affected Communities United in Action and Women Affected by Mining United in Action are fighting against the nexus of carbon capital and the state across the country. Every progressive organised formation which takes seriously questions of land, decolonisation and the achievement of socioeconomic justice, cannot ignore the importance of extending solidarity to these community organisations. In uniting the struggles of the working classes, these community organisations are as important a layer as organised labour, the student movement and young people more broadly to chart the course towards a post-capitalist world.

Issues concerning land cannot be divorced from homelessness and hunger, both of which have been unseen and normalised within capitalist society, extending even onto university campuses. There is a pressing need for both quality public housing – envisioned in the Climate Justice Charter as part of “eco-communities, villages, towns, municipal rental schemes and cities” – and food sovereignty, a systemic alternative championed in the charter, which gives people and communities ownership and control over the means to create their own food systems.

Food sovereignty, as Courtney Morgan and Katherine Brown argue, is the only solution to the hunger crisis and is a departure from the status quo of corporate agriculture which actively perpetuates it. In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic and food price increases, the question of starvation is a real one that is effectively and criminally being ignored by the state, which has failed to implement policy to meet one of the worst droughts in this country’s history. These problems are not uniquely our own – they stretch across borders, embedded within the same global order of neocolonial, neoliberal capitalism.

In the closing lines of the Pale Blue Dot meditation, Sagan addresses the irresistible prospect of interplanetary travel – now dominated in the public imagination by the fantasies of the billionaire class like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. Faced with an imperilled humanity not yet ready to leave Earth, Sagan offers again a sobering reality: “Like it or not, for the moment, the Earth is where we make our stand.”

A programmatic intervention in the trajectory of our society is necessary, steering us away from the carbon capitalism that birthed the crisis and in the direction of an international, intersectional eco-socialism for the masses. The decolonial project of our generation, the perspectives of our student activism, must be informed by this vision. As the latest IPCC report clearly states, the clock is mercilessly ticking. Let the ticking of that clock ring in our ears. And let us march in step. DM/MC

Raees Noorbhai is a writer and activist. He is the National Coordinator of the Socialist Youth Movement and the Chairperson of the Student Forum at Wits University, where he is doing his postgraduate studies in Astrophysics.

Oh to be young and naive !! Ideology is fuelled by emotion rather than reality and knowledge of the real world issues all people face. Othering is so dangerous and intellectually lazy.

Your socialist nirvana requires a world where things are made, people take risk, work hard and are rewarded for that.

Time to get a real job !