COVID-19

Effective ways to increase vaccination uptake: Learn the lessons from Aids treatment campaigns

The Universities of Columbia and Wits recently held a five-day symposium with a range of experts debating topics linked to finding effective ways to increase vaccination. Maverick Citizen was the media partner to the symposium and Mark Heywood made the closing reflections. This is an edited version of his speech.

This week, in a range of stimulating and informative presentations [the full programme is here], scientists covered topics ranging from current concerns about the uptake of childhood vaccinations for diseases other than Covid, to vaccine hesitancy and how to identify and overcome the practical barriers to vaccine uptake.

The input of experts gave us an opportunity to do a virtual stock-take on our response to Covid-19, particularly since the advent of safe and effective vaccines in late 2020. The symposium offered a wealth of information, which is now very important to distil and make accessible to many more people.

I say this partly because whilst technologies like Zoom make it possible to sit in a “room” with the world’s best experts, this symposium is also an example of how the digital divide deepens inequality — and in this instance the inequality (as is so often the case) is about a fundamental human right: the right of everyone to have access to life-saving health information.

This is symptomatic of a deeper pathology of Covid-19:

- A lot of the discussion about Covid has taken place amongst political and health elites;

- By time it gets handed down to ordinary people, it comes as pre-cooked instructions or “recommendations”, that don’t allow thinking and ownership by the people who receive it, hence the hesitancy.

For example, the title of one day’s discussion was, Vaccine hesitancy — what makes Covid vaccination different? Speakers pointed to vaccine hesitancy as something we have seen since the advent of vaccines, which is true. And yet clearly there is a difference to early 20th- and early 21st-century vaccine hesitancy.

I will blame this hesitancy on what I call “the Covid-paradox”, which for those with longer memories might remind you of what Aids activist, Australian judge Michael Kirby once termed “the Aids paradox”.

The Covid paradox is this:

- Inequalities have sharpened since the commencement of the last great viral pandemic, HIV. In particular, the defunding of public health and austerity means millions of people have less access to quality healthcare services, and doctors especially (certainly in developing countries).

- But simultaneously there’s been a revolution in media, which means they have more access to health information and misinformation. Hence the coming into being of what the WHO has called info-epidemiology.

This makes meaningful communication more important: and here it’s important to distinguish between communication that creates awareness and that which leads to understanding/knowledge with which people can make informed decisions. Once upon a time, we placed a premium on informed consent. In this epidemic, particularly in relation to decision-making about vaccinations, it seems much less important. It shouldn’t be.

The importance of social science

Another of the things that has struck me repeatedly during presentations this week is that health planners, advocates and governments should stop abstracting Covid from the other great issues of our time: generalised distrust of government, anxiety, anger, despair.

This is why “following” social and political science is as important as medical science.

It is surely a problem that many governments (including SA’s) have relegated social scientists to being media commentators, rather than integral to planning and implementation. It is also a problem that civil society seems to be minimally involved in the planning and implementation of Covid-19 strategies. Why is this?

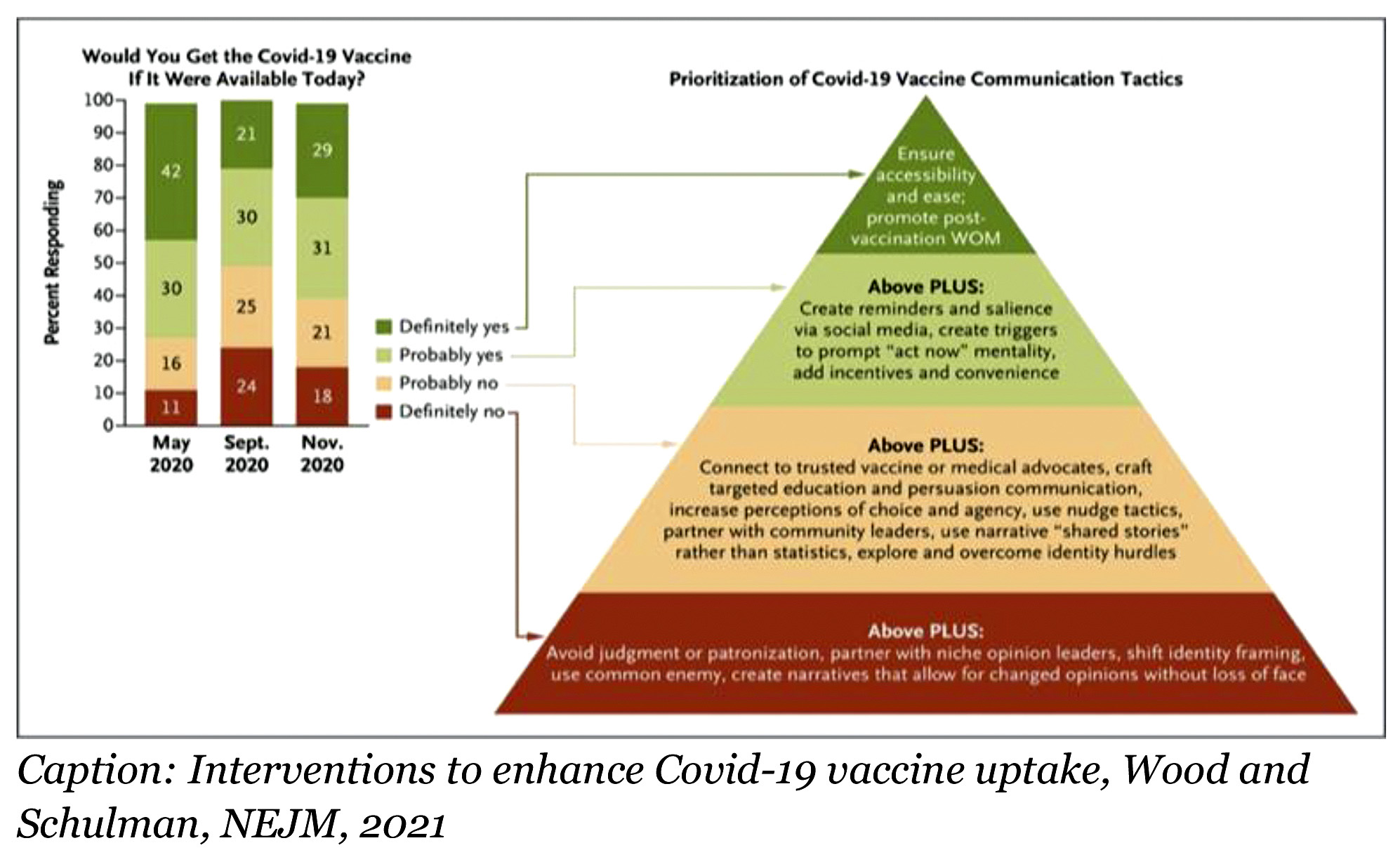

For these reasons, I was glad to see in Dr Wafaa’s El-Sadr’s presentation on vaccine mandates, a diagram of a pyramid of “interventions to enhance Covid-19 vaccine uptake” (see below) that recognises that people are not hesitant because they are stupid. Actually, they are hesitant because they are thoughtful.

Interventions to enhance Covid-19 vaccine uptake, Wood and Schulman, NEJM, 2021.

Poor people ask themselves: “Why this sudden concern with our health and lives when you ignore us most of the time?”

“We don’t usually trust big pharmaceutical companies who prioritise profit over health and make medicines that are unaffordable, so why now?”

Consequently, my belief is that vaccine campaigns meet people at the level of their uncertainties, not our certainties. (See, as an example, this story in Maverick Citizen about the ‘Eastern Cape doctor on a mission to assure men their virility is not affected by the Covid-19 jab’)

We have to locate our advocacy for vaccines in the context of people’s experience of the last 18 months: in SA, between March and May 2020, there was a great swelling of common purpose and a willingness to sacrifice for an ill-conceived blunt lockdown — but that trust was later abused, as we have seen in the shocking PPE corruption scandals. Common purpose has been replaced with mistrust and anger, which is now playing out in some ways in relation to vaccine take-up.

Bearing all this in mind, two key themes I have extracted from all the presentations are:

- We must go back to the basics we learnt in the response to HIV — the importance of community mobilisation; of community treatment literacy that takes the trouble to teach people the science so they can make informed decisions.

- We must centre people: it is ironic that although people are the object of vaccination, they are often the last of our considerations (in one presentation this week, people were at the endpoint of a six-step algorithm rather than its beginning).

On this foundation I also want to make a few specific comments on some of the issues we have discussed this week:

Vaccine hesitancy

We should problematise the ease with which we resort to talk of “vaccine hesitancy”: it quickly became part of the new nomenclature of Covid, but do we give it too much credit?

On the radio I heard Dr David Harrison, who is now running SA’s Vaccine Demand Acceleration Strategy, talk about “vaccine inertia” (rather than hesitancy), pointing out that this is “more due to people’s circumstances than antipathy”. If we accept this, as I do, we should concentrate on getting all the willing vaccinated: doing that will probably draw the hesitant in its wake.

We must not forget that access is still a major issue. Just look at data presented this week regarding vaccination rates amongst those with medical insurance (38.4%) versus the uninsured (18%). In response, Sarah Downs wrote in the chat that it “seems like for the uninsured there is an access problem, not a willingness problem”.

Or, as Amanda McLelland said, in some of our countries we have “a long way to go before vaccine hesitancy becomes the major bottleneck”. I believe that is the case in SA and warn against “vaccine hesitancy” being used as an excuse for poor communication, lack of political will and lack of imagination.

Researchers report the same pattern when you compare vaccination rates between people who live in urban formal dwellings versus urban informal shelters or people with cars versus people with no cars. The answer is to “let people who are trusted in communities take vaccines to the people”, as we can see from this recent article in Maverick Citizen about a vaccination campaign in an informal settlement in Soweto.

Vaccine mandates

Excellent presentations were made on legal and ethical issues governing making vaccinations mandatory, particularly for certain groups of employees, like health workers, or front-facing public and private employees whose jobs require regular and close interactions with the public.

Few human rights are absolute and coercion can be justified in narrow and well-defined circumstances. According to veteran human rights lawyer, Halton Cheadle, this is supported by human rights law. Ethicist Keymanthri Moodley says it is also permissible ethically.

However, in my view policy-makers still need to consider the long-term disadvantages for past, present and future vaccination programmes of resorting to mandatory vaccinations, rather than stepping up public education, improving communication and engaging people’s fears directly.

Where do we go from here?

Given the relatively low rates of vaccination in South Africa, even though we now appear to have adequate supply, it is clear emergency surgery is needed to resuscitate the vaccine response.

As David Harrison has pointed out in this important article on Vooma vaccinations, meeting the government’s target of vaccinating 70% of the adult population by the end of 2021 is essential to slow down deaths and prevent a fourth wave of Covid-19 overwhelming our already exhausted health workers.

But even as we step up to the short-term challenges, we need to be identifying and fixing the underlying social pathologies that have allowed Covid to cause so much death and disruption, particularly the problems of vaccine apartheid and weakened health systems. For this reason, it is vital that we do not lose sight of proposals made by the Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness and Response. Their proposals are the game-changers that will not only make it possible to control Covid, but also protect us against what Prof Helen Rees called “Pathogen X” (an even more deadly respiratory pandemic that scientists have long predicted).

We must also not be found guilty of having an exclusionary focus on Covid to the exclusion and detriment of other health issues. The theme at the start of this week’s symposium was the negative impact of Covid lockdowns on childhood vaccination generally. But we have accumulating evidence that this adverse impact has spread into almost all aspects of health and healthcare.

So in conclusion, I want to return to words that were quoted at the beginning of this week from the 19th-century German physician, Rudolph Virchow, someone who is arguably the father of public health.

“Medicine is a social science and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution; the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution.” DM/MC

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider