Maverick Citizen OP-ED

We can do it! Mass vaccination can be achieved through empowered community leadership

We can reach our vaccination targets, but only with the right approach.

Kate Alexander is a professor of sociology and South African Research Chair in Social Change at the University of Johannesburg. Bongani Xezwi is a researcher at the University of Johannesburg and a community organiser in Protea South.

Protea South is an informal settlement on the south side of Johannesburg with a population of approximately 40,000. On Wednesday 29 September, a mobile vaccination unit visited for the first time, and people came out in force. They walked. This was just a small unit, with a couple of vaccination booths, not a large drive-through ‘pop-up site’.

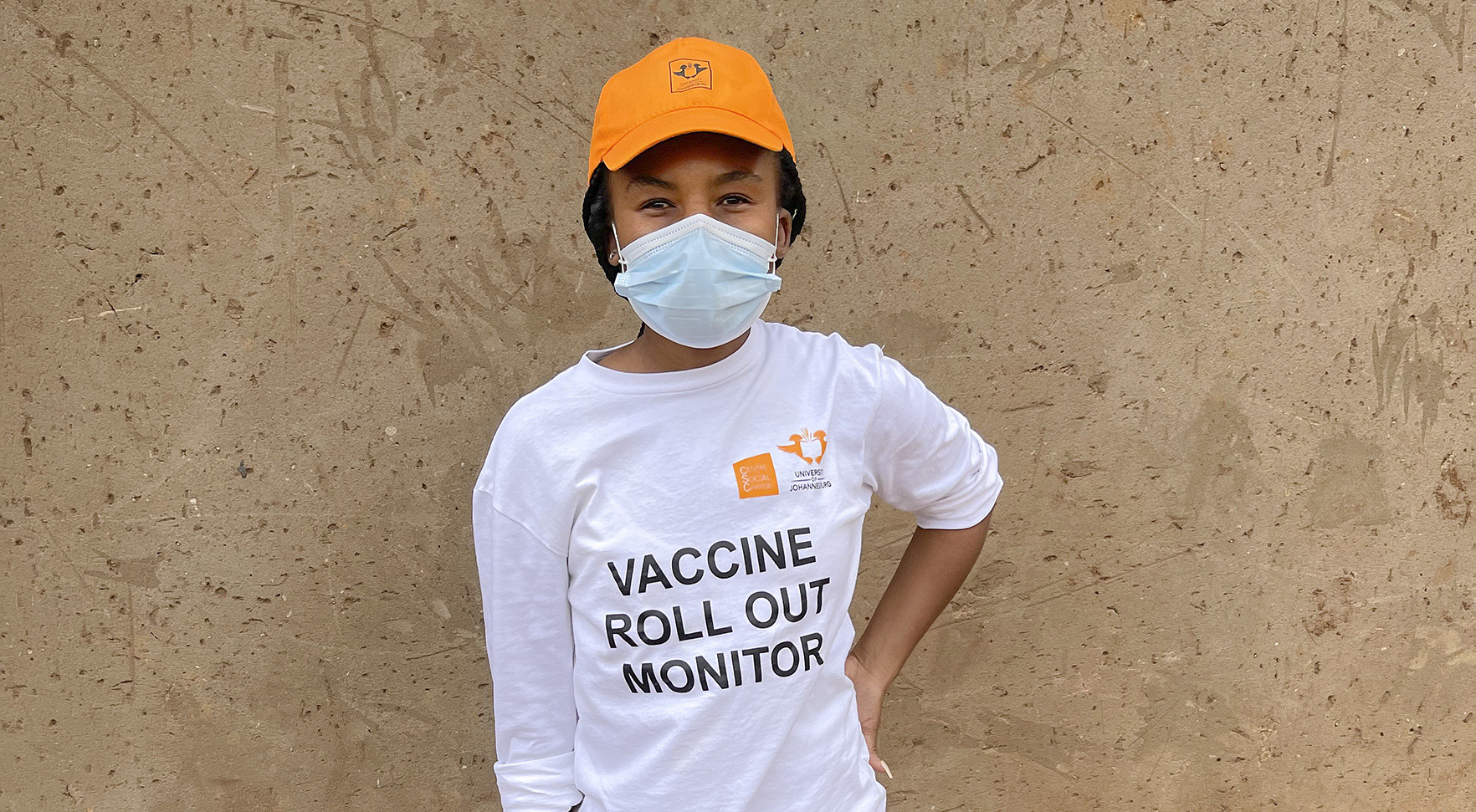

Some of the young volunteers relax after a long, hot day at the Protea South informal settlement vaccination site. (Photo: Supplied)

Hundreds sat outside on plastic chairs. Hundreds more joined the queue to get a chair including women carrying babies. The small vaccination team worked hard but was not prepared for the turnout. Only about 400 people got their vaccine and about 200 people were turned away soon after noon. Many returned the next day, and new people came as well. Even before the unit and chairs had arrived, the queue was already about 200 metres long. Even without marshals, everybody wore a mask and practiced social distancing. But after two days, the unit will have moved elsewhere, with thousands from the settlement still wanting the vaccine.

This impressive gathering was the product of well-organised community mobilisation. With government worried by the declining rate of vaccinations across South Africa, this case study can provide a welcome lift and a valuable example for community activists elsewhere.

Nokuthula Dlamini, leader of the Protea South vaccine mobilization volunteers.

(Photo: Supplied)

It is not the first illustration of a neighbourhood mobilising to get vaccines to the people. For instance, doctors in Laudium outside Pretoria have worked with local residents and the provincial department of health to get some 20,000 people vaccinated at a community site. Elsewhere, traditional leaders have often played a positive role.

However, this is the first case of community mobilisation in an informal settlement that we know about. This matters a great deal. Informal settlements are often densely packed and have poor sanitation, providing fertile conditions for the rapid spread of Covid-19.

The UJ/HSRC Covid Democracy Survey conducted at the end of June and early July 2021 showed that only 6% of informal settlement residents had been vaccinated, compared with 18% of people in suburbs. If people in informal settlements can be vaccinated in large numbers it will minimise the impact of the fourth wave.

Mother with baby queuing to get a chair at the Protea South informal settlement mobile unit. (Photo: Supplied)

More broadly, vaccine inequality remains intense. Recent government figures show that 50% of the insured population has first-dose vaccination coverage, compared with 25% of the uninsured. The difference between these two figures cannot be explained by greater hesitancy among poorer people. Indeed, drawing on the UJ/HSRC survey again, hesitancy is higher in the suburbs than in informal settlements, townships and rural areas.

Five metros account for 40% of the unvaccinated population, and about one in three of the unvaccinated population live in Gauteng. If the government can get vaccines to all the people in an equitable way and if Gauteng can get its roll-out strategy right, it would make a big difference to the whole country and reduce Covid deaths.

The authors of this article have long explained the benefits of community mobilisation, doing so partly on the basis of earlier research in Protea South (also Mark Heywood), and they have shown, in relation to vaccination, that access is the big issue in poorer areas.

People with cars in their household are almost twice as likely to be vaccinated as those without. The government needs to place emphasis on getting mobile units and new sites to informal settlements, where pharmacies and larger clinics are few and the cost of travel is relatively expensive.

Young volunteers assist with registration at the Protea South informal settlement mobile unit.

(Photo: Supplied)

Now we add a new argument: vaccination must be community-led, at least in those areas where community leaders are prepared to take a lead. We have a strong example of how this can work. It highlights the importance of involving young people, those from the age group where hesitancy is greatest and vaccination lowest. It is not just a matter of getting ‘vaccines to the people’, it is about getting mobile units to informal settlements.

How was success achieved in Protea South?

First, leadership did not come from traditional, older leaders, it came from a younger generation of activists, most of them unemployed. They were supported by their ward councillor (ANC) and their PR councillor (DA), but they did not wait for these sympathetic politicians to initiate action. Most of the youth were part of a team affiliated with the Community Organising Working Group (COWG) and with the newer National Vaccine Monitoring Group (NVMG).

Hundreds of people turned out at the Protea South informal settlement community vaccination site.

(Photo: Supplied)

Secondly, a core of the activists had received virus and vaccine training and had prior experience of popular education. A critical part of the work was door-to-door conversation. Activists used flyers with a question-and-answer format, which responded to the actual questions being asked, rather than merely relaying information. The flyers were available in local languages, not just English (unlike most government communication). Murals by a local unemployed artist added visibility to the vaccine campaign and loudhailers contributed to the atmosphere and arguments.

Thirdly, activists targeted older people but also encouraged their household members to accompany them to the vaccination station. In future, more younger people will join in. A taxi was organised for the day and older and disabled people were offered lifts. As they went around the settlement, the mobilisers kept a list of those who wanted to be vaccinated, which meant that people were encouraged by seeing that their neighbours also wanted the vaccine. Later, at the vaccination site, the activists assisted people with their EVDS registration.

Fourthly, the activists knew where the older people lived because they were neighbours or lived nearby in the settlement. This also meant the activists were known by community members, and they were respected and trusted. Nokuthula Dlamini, the COWG and NVMG team leader for Protea South, explained that people knew her from previous campaigns: on GBV, popular education and feeding vulnerable people in the early days of the pandemic, delivery of water and electricity, and other problems facing the community.

This week’s campaign was different from earlier popular education around vaccines because there was a focus: the mobile unit. Now the issue was concrete: will you come to be vaccinated at this place and this time? In practice, the two problems confronting the roll-out came together, with conversations about hesitancy intertwined with those about access.

The government’s project plan for accelerating demand for vaccination includes a thoughtful line about “sites that create a strong sense of community pride.” The little mobile unit on a dusty sports field was Protea South’s site and there was a sense of pride. A few, but not many, people had been vaccinated at sites in local townships, but this time the community turned out in strength, it was a collective activity.

In conversation, we heard about a new informal settlement, close and recently established. The Protea South activists invited residents to their vaccination station, but, no; the people from the new settlement were waiting for their own mobile unit.

At a micro-level, the state’s representatives running the vaccination station and the group of civil society young activists worked well together. At the moment of potential conflict, when people were told there was no vaccine left, representatives from both sides calmly explained the situation. At the end of the first day, the state’s representatives requested that civil society bring their 200 chairs, volunteers and PA system again the next day. This was not a problem for Nokuthula and her comrades, and they had already decided that, as on the first day, they would also bring water and oranges to quench thirsts.

One hopes that this small story can become part of a larger narrative. Civil society is independent of the state, not its servant. The state has vaccines and nurses, which people need to survive, but civil society can mobilise in a way that, hitherto, the state has failed to do.

None of this is possible without support. Unemployed youth lack resources. The Protea South pilot was backed by a University of Johannesburg community action research project. The cost was relatively small: food for volunteers, flyers, paint for murals, hire of a taxi, PA and chairs. However, while researchers can assist in finding solutions, they do not have the capacity of an implementing agency.

A new programme to support NGOs with vaccine mobilisation is backed by two philanthropic donors, the DG Murray Trust and Tshikululu Social Investments. This is a worthwhile enterprise, but underfunded, absorbing a tiny proportion of the money committed to the rollout.

The government has come around to an appreciation of an ‘all of society’ approach to vaccination, but it is still stuck in an old way of thinking about civil society as merely ‘social partners’: business interests, unions, faith-based organisations and, perhaps community leaders.

In Covid South Africa, only 15 million people are employed. The majority of the 40 million adults the government seeks to vaccinate are jobless.

A new civil society of unemployed and underemployed young people is emerging. It has the enthusiasm and capacity to help win the war against Covid. Whether this will happen depends on the willingness of the state and old civil society to allow it to happen. DM/MC

Kate Alexander is a professor of sociology and South African Research Chair in Social Change at the University of Johannesburg. Bongani Xezwi is a researcher at the University of Johannesburg and a community organizer in Protea South.

"Information pertaining to Covid-19, vaccines, how to control the spread of the virus and potential treatments is ever-changing. Under the South African Disaster Management Act Regulation 11(5)(c) it is prohibited to publish information through any medium with the intention to deceive people on government measures to address COVID-19. We are therefore disabling the comment section on this article in order to protect both the commenting member and ourselves from potential liability. Should you have additional information that you think we should know, please email [email protected]"

Become an Insider

Become an Insider