CURIOSITY

From the ancient city of Knossos: The Lady of the Ring

An intricate gold jewel fashioned more than 3,000 years ago provides a window on an ancient culture that has much to teach the modern world.

The language of a tiny, engraved ring, unearthed on the island of Crete, has teased and perplexed scholars for more than a century. It also gives us a sense of the unique people who made it.

The name they called themselves is lost, but the British archaeologist who rediscovered their civilization and unearthed the ruins of the ancient city of Knossos, Arthur Evans, called them “Minoans”, after their mythical king, Minos.

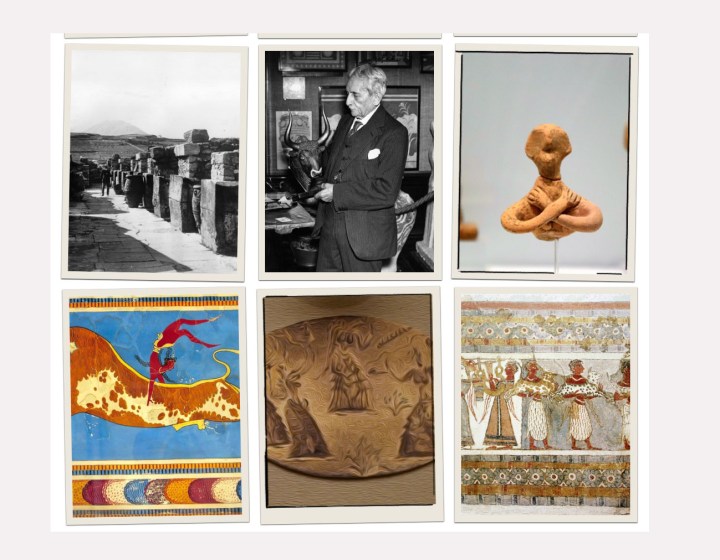

9th October 1936: English archaeologist Sir Arthur John Evans FRS (1851 – 1941) holding a Cretan sculpture of a bull’s head at the exhibition of relics from Knossos or Cnossus at the Royal Academy, London. (Photo by David Savill/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Half-memorialised in the myths of Theseus and the Minotaur and Icarus, who flew too near the sun, they built Europe’s first centralised state, which reached its peak a thousand years before classical Greece.

The Minoans seem to have believed in a female supreme deity, and embraced an astonishing degree of equality between the sexes. Their religion is thought to have revolved around the once widespread practice of theia mania (divine madness).

Their art glows with a love of nature and belief in its sacred potency. They remind us that there are no “primitive” and “advanced” societies, and that history is not a one-directional ascent.

The writing of the Minoans, Linear A, is still undeciphered, but hundreds of their seal rings have been found, often portraying cult scenes or magical hybrids like the bull-headed Minotaur. But none is as beautifully crafted, or pregnant with esoteric meaning, as the famous “Isopata ring”.

Evans found it in a tomb near the ruined temple complex of Knossos, where it had lain for 3,500 years. He believed it was not used as a seal, but worn round the neck or the wrist as a mark of status and an “apotropaic” (evil-deflecting) talisman.

Delicate, dreamlike, the Isopata jewel was engraved in exquisite detail under a magnifying lens. German archaeologist Gerhard Rodenwaldt remarked that it conjured for him the “enchantment of a fairy world”.

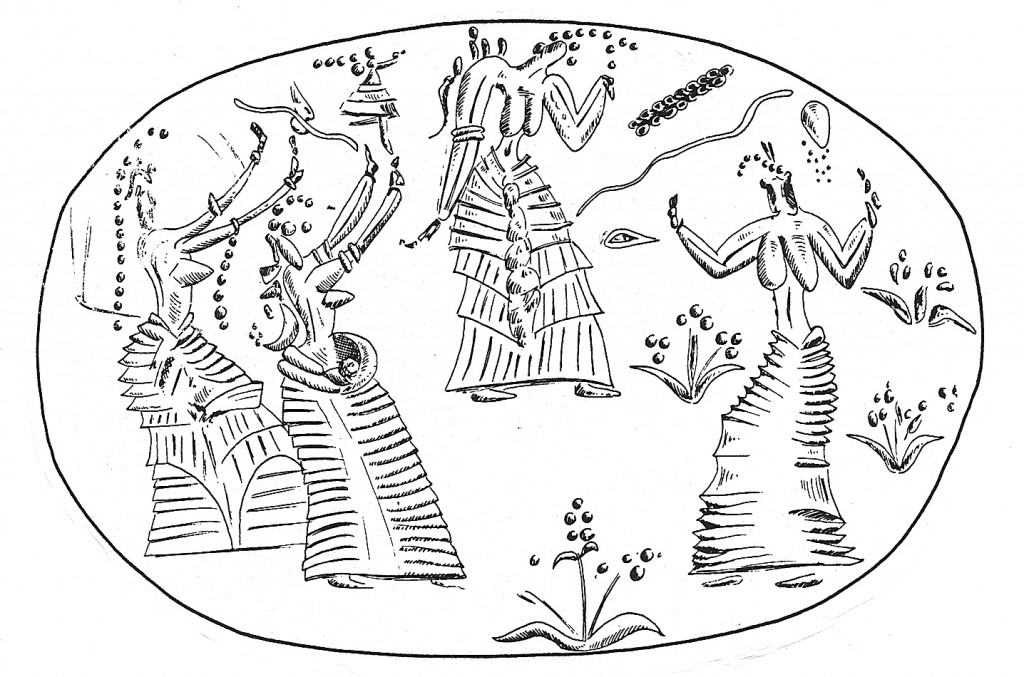

Illustration of a gold ring from the Isopata tomb near Knossos depicting an envisioned epiphany. (Heraklion Museum). Source: Flickr

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete. Gold signet rings

Left: “the Ring of Minos” depicts the Epiphany and cult activities, Knossos 1500-1400 BC.

Right upper (18): the Isopata signet ring, Knossos Isopata grave 1600-1400 BC.

Right lower (19): Knossos 1500-1450 BC; Source: Flickr

The ring has four female figures in long Minoan flounced skirts and aprons, wasp-waisted and bare-breasted, dancing among flowers. Above them, in the celestial realm, a much smaller skirted figure descends to Earth. Also in the “sky” behind the dancers float cryptic symbols – snakes, an eye, an oval surrounded by tiny droplets, and a chrysalis or ear of wheat.

The difficulties of interpretation are enormous, but the asymmetry of gesture, scale and position points to the elevated status of one figure. Centrally placed, she towers above the others, who stretch out their arms towards her in adoration. Inclining her head and raising her hand to her brow in “the Minoan salute”, she acknowledges the ecstatic tribute of the adorants.

What does this tableau mean?

Most scholars believe it shows an epiphany of the Minoan Great Goddess, invoked in a quasi-shamanistic ritual by the rapture of the dancers. Summoned to Earth, she descends through the heavens, a tiny, childlike figure. Then, made radiantly manifest, she stands among mortals, “full of grace and truth”.

The Minoans almost certainly thought of their chief deity as female, the source of animal and plant fertility, and the celestial objects on the ring tell us that her epiphany has cosmic resonance.

The eye may be a solar symbol, and the ear of corn the blazing double star Spica, held by Virgo, the maid. Other floating items have also been identified as constellations: the snake as the water-serpent Hydra, the oval as Taurus the bull, and its surrounding drop-like stars as the Hyades, the “rain-makers” that rise at onset of the wet season. The snake and the bull were Minoan cult animals.

A maritime and agrarian people, the Minoans knew the movement of the heavenly bodies and their relation to the circle-dance of the seasons. Their religion and art – inseparable – mirror this. The abundant celestial imagery at Knossos includes the eight-pointed star, originally the symbol of Inanna (who was later identified as Ishtar by the Akkadians and the Assyrians), the Mesopotamian Queen of Heaven and the planet Venus.

It is striking that on many Minoan seals, only women are shown as divinities or cult practitioners. When depicted, men – usually youthful and near-naked – serve high-ranking females; the women often sit while the men remain standing. The imagery is of fervent veneration, but strangely unerotic. The Goddess personifies sex but is also the virgin Persephone, the goddess queen of the underworld, also known as Kore, a vegetation spirit who withdraws to the underworld for half the year and bursts from the earth in spring.

Minoan religion seems to have turned around nature’s eternal cycle of birth, death and regeneration. Crete was also the home of the “corn mother” Demeter and the dread creatrix Rhea, who birthed the Milky Way with a spurt of her breast milk across the heavens.

Another ring. Image: Supplied / Flickr

Image: Reinier de Rooie / Flickr

Image: Supplied / Flickr

Minoan iconography suggests that women, fashionably coiffed and dressed in revealing bodices, had a status, freedom and confidence otherwise unknown in the ancient world. They are shown taking joyful part in public ceremonies and athletic rituals such as bull-leaping, and seem to have been central to religious and civic life.

“The culture on Crete in around 1,600 to 1,500 BCE is the closest thing we have to a matriarchy. And that’s massive,” remarks classicist John Younger.

He believes, for example, that the large “lustral basins” found in Knossos may have served as shrines for menstruants, who were not isolated and set apart. Initially, Evans saw the famous wavy-backed stone throne in the palace as the seat of Minos. But the modern tendency is to see the throne room as the sequestered domain of the Goddess, where the chief priestess presided over epiphanic rites.

circa 1910: The ruins of the palace of Minos at Knossos or Cnossus, discovered by English archaeologist Sir Arthur John Evans, who later rebuilt and repainted large parts of the Minoan palace. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

circa 1900: The ruins of the palace of Minos at Cnossus or Knossos. English archaeologist Sir Arthur John Evans excavated the ancient city and discovered the remains of a civilisation there. He later rebuilt large parts of the Minoan palace. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It has been speculated that “Minos” was the hereditary title of a priest-king whose authority was shared with a high priestess, and that their joint reign was periodically reconfirmed, amid joyous festivity, by a hieros gamos (sacred marriage).

A reconstructed room stands in the partially-reconstructed ruins of the ancient Minoan city of Knossos on the island of Crete on August 22, 2015 in Knossos, Greece. Knossos dates from the Bronze Age, is Europe’s oldest known city and was excavated thoroughly in the early 20th century by British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. Crete is a popular summer tourist destinaiton. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

What happened to the Minoans, their society and their religion?

One school of thought is that patriarchal horse-borne warriors from Mycenae on the Greek mainland invaded Crete in about 1,450 BCE, sacking all the Cretan palaces except Knossos and breaking the sway of the priestesses.

Tablets recovered from Knossos in Mycenaean proto-Greek, known as Linear B, list only one “priestess of the wind” who received olive oil for cult purposes. But in possible relics of an egalitarian past, the tablets also place women alongside men as overseers in Crete’s great woollen textile industry, and draw no distinction between male and female rights in land.

The ‘raving ones’

Will they ever come to me, ever again,

The long long dances

On through the dark till the dim stars wane?

Shall I feel the dew on my throat, and the stream

Of wind in my hair? (The Bacchae)

A thousand years after the Isopata ring was made, the playwright Euripides looked back in fascinated horror at the orgiastic revelry of the Maenads, mythical female followers of the Greek wine god Dionysos.

The “raving ones”, with their frenzied dancing and singing, were almost certainly a distorted echo of the ecstatic cult of the Goddess. The chorus in the “Bacchae” sings of their emancipation:

“To stand from fear set free, to breathe and wait; To hold a hand uplifted over Hate…”

Evans believed Minoan religion bore elements of shamanism, a widespread prehistoric practice that uses dancing, “sonic driving” through chanting and drumming, fasting, sensory deprivation, and narcotics to achieve a state of possession and “see” or feel the spirit world.

The heads of the Isopata figures are oddly featureless, and surrounded by sprays of dots that may signify intoxication. The Minoans knew wine and mead; the opium poppy capsule decorates their ceramics and seals. Figurines found at mountain sanctuaries also point to a repertoire of stylised ritual gestures that, held for long periods, may have been used to induce trance states, much like the yogic asana.

The ancients recognised the relation between ecstasy (Greek ecstasis – “standing out of oneself”) and inner equilibrium: ecstatic rites “sought to secure for him who was correctly entranced and possessed a release from troubles”, wrote the philosopher Plato.

A Victorian evolutionist, Evans viewed the Minoan religion as a “primitive” forerunner of “civilised” faiths such as Christianity. We now see ecstatic possession as a permanent undercurrent in all belief systems, which seeks to counterbalance the path of law, tradition, hierarchy and scriptural commandment.

Image: Supplied / Flickr

Minoan society offers a unique paradigm: it is an historical, rather than utopian, social order built on ideological foundations that set it apart.

Throughout the long testosterone-driven ages, the warrior ethos, the masculine god and the subordination of women have been closely connected. But the Minoans, worshipping the Goddess and perhaps ruled by a sacred priesthood of both sexes, seem to have fostered the arts of peace.

Minoan Crete was a religious, not military enterprise. Its palaces were fortified, but not, like the hilltop fastness of warlike Mycenae, with “cyclopean” stone walls; its weapons served a largely ritual purpose, and there is no evidence of a warrior caste. its modest maritime empire seems to have grown from trading contacts and cultural influence, not force.

Image: Supplied / Flickr

While Mycenaean iconography revolved around soldiers, horses, chariots and weaponry, the Minoan teemed with wild animals – monkeys, deer, flying fish, octopus, swallows – and flowering plants such as the saffron crocus, iris and wild rose.

The Isopata ring speaks of this attachment to the natural world, the realm of the Goddess as Potnia Theron, the Mistress of Animals.

It is beside the waters, where the white-petalled Pancratium lily grows, that the worshippers tryst with her. Heads among the stars and bare feet stamping the dewy sand between the flowers, they dance forever to the murmur of the dolphin-thronged sea. DM/ ML/ MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I’ve wondered whether the subordination of women in patriarchal societies stems from the fear men might feel because women give birth, are responsible for the continuance of the people. Women in general seem to prefer peace, so the next generation are protected, while men prefer war so their seed can be spread. Probably some truth in all this, also that no society lasts forever….