MAVERICK CITIZEN

Writing Large: An interview with Michela Wrong, author of ‘Do Not Disturb’

In her latest book, Michela Wrong writes that, ‘Few narratives possess the seductive power of the Rwanda Patriotic Front’s redemptive tale of humiliated-refugees-reborn-as-crusaders, righteous warriors returning to a lost motherland to save their brothers from the forces of Absolute Evil and then, on the toxic ruins of a racist society, building a spotless, disciplined, tech-friendly African Utopia.’ Not someone predisposed to political fairy tales, she sets about to demolish it.

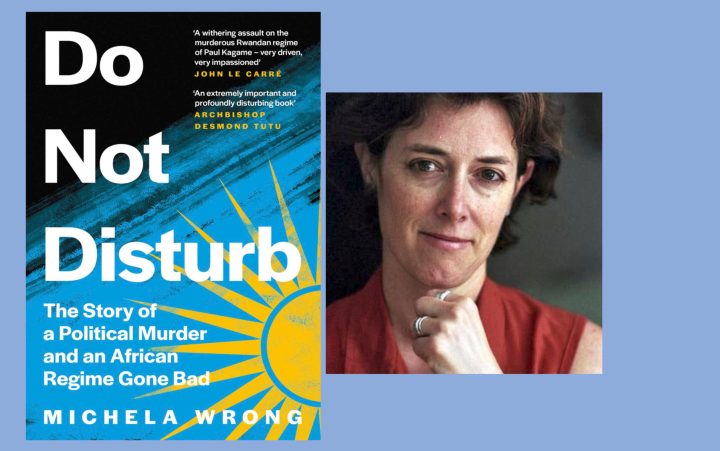

Michela Wrong’s latest book Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad was published on 1 April 2021. It has garnered two very different sets of responses. Many reviewers describe it as a very brave book, brave because it sets out to document and dismantle the myths that have been built up around Rwandan President Paul Kagame and the “miracle” of Rwanda’s post-genocide development. But others have accused Wrong of being racist and stereotyping Africa and Africans.

Let me say up front that I place myself in the first category.

I have admired Wrong’s writing since her first book, In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz (published in 2000), and followed it through I Didn’t Do it For You: How the World Used and Abused a Small African Nation (2005) and It’s Our Turn to Eat: The story of a Kenyan Whistle-Blower (2009) — all well-researched histories of Africa’s colonial and post-colonial struggles.

But as I read Do Not Disturb I knew that this one would be bound to provoke a fierce reaction, one that would seek to kill the book, if not the writer.

Last week I interviewed Wrong. One of my first comments to her was that Do Not Disturb feels very personal and passionate. I asked her to explain what motivated her to write it.

Yes, she agreed, it is “my angriest book yet”. But she says that the anger was also “at myself”. Wrong was in Kinshasa (then the capital of the former Zaire) in 1994 when the genocide took place. She reported extensively on Rwanda and the region in the months and years that followed. But, she says, “I’m angry because as a journalist I got it wrong. That is not a comfortable position to be in as a writer… I was completely impressed by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF); we thought they had ended the killing; we believed their talk of ethnic reconciliation.”

President of Rwanda Paul Kagame . (Photo: EPA-EFE / Dai Kurokawa)

Wrong, through nearly 30 years of experience, has a deep knowledge of the shifting politics of the Great Lakes region and Kagame, who she interviewed “once, maybe twice” is by default the central character in her book. However, as she set about puncturing the Kagame myth she must have known that a lot was at stake — she was broaching a subject that, as described in the book, had got several other journalists killed.

There could be little doubt it was likely to bring a similar wrath down on her own head. She writes in the final chapter that, “Ever since I began writing this book, I’ve been grimly aware the same accusation — of ‘revisionism’ and downplaying the genocide — would one day be levelled against me.”

She wasn’t wrong.

But Wrong’s no rookie writer. She has had a rich and varied journalistic career. I ask about her influences as a writer. No one jumped immediately to mind, but she notes that “like many journalists” she read a lot of George Orwell in her youth and hopes that her writing conveys “my own sense of intrigue and curiosity to the reader. Whether it’s cycling or fashion or the Kurdish exodus out of Iraq, the topic is not important; it’s about conveying to your reader why this is a fascinating subject and an important moment.”

Do Not Disturb certainly does that.

Room 905

It is a gripping and compelling read. It is framed around the assassination in room 905 of the Michelangelo Hotel in Sandton, Johannesburg, on New Year’s eve 2013, of one-time Kagame ally and co-founder of the RPF, Patrick Karegeya. That night, the charismatic Karegeya was lured to a room in the Michelangelo by a Rwandan hit squad, sent on the instructions of Kagame. After strangling him, the murderers hung a “do not disturb” sign on the door and were whisked out of the country hours later.

Patrick Karegeya. (Photo: Supplied)

Her book records how, many years later, in April 2019, an inquest into his death held in Joburg concluded that he had been murdered. She notes that according to the Hawks, the operation was “directly linked to the involvement of the Rwandan government”.

Wrong says that the book’s “trigger” was Karegeya’s murder. “If he hadn’t died I wouldn’t have written the book.” However, while that might have been stuff enough for a thriller, Wrong uses Karegeya’s fascinating life story to recount the contemporary history of Rwanda. This works because Karegeya’s life is inextricably tied to the tumult of the Great Lakes region of central Africa. The last few chapters of Rwanda’s history are at least in part the interwoven story of a band of brothers — Karegeya, Fred Rwigyema, Paul Kagame, General Kayumba Nyamwasa — most of whose families were driven out of Rwanda in the late 1950s or early 1960s to join the Ugandan Banyarwanda.

When I draw parallels between her style and that of writers like Thomas Packenham (The Scramble for Africa) and Adam Hochschild (King Leopold’s Ghost and Bury the Chains), Wrong recognises the similarities in their approach.

“What we are all doing is trying to inject the human angle into these stories, because we don’t believe that historical processes take place without the individual footprint of these big players, and the characters in Africa are so florid, on whichever side, whether you are talking about the explorers or the politicians, the Bismarcks or Lord Lugards of this world or the African chiefs and sultans they were encountering and whose lands they were stealing. These are larger-than-life characters. They come out of the page at you.”

Together the “59ers” — the generation of Tutsi people who fled from Rwanda to Uganda in response to post-colonial pogroms against Tutsis by the Parmehutu Party — start their own long walk to freedom by cutting their teeth as lieutenants in Yoweri Museveni’s armed struggle to overthrow the second Presidency of Milton Obote in Uganda (which, after an increasingly successful bush war, was preemptively toppled by his own generals in 1986). With Museveni in power, they then went on to build their own movement in Uganda before launching a four-year guerilla insurgency (between 1990 and 1994) intended to return and restore the rights of the beleaguered Tutsi minority in Rwanda.

Thus her book covers their fascinating years in Uganda, the genocide (who really shot down Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane?), its aftermath and finally the cruel calculated consolidation of the government of the usurper, Paul Kagame. As to how and why Wrong and others consider Kagame a usurper… read the book.

Tragic heroes: we few, we unhappy few

Karegeya embodies many of the characteristics of a Shakespearean tragic hero and the book contains many fascinating anecdotes and insights into his rise and fall.

Wrong describes, for example, how in April 2006 she met Karegeya in the company of English spy novelist John le Carré on the terrace of the (in)famous Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali. Wrong recalls Karegeya and le Carré hitting it off immediately, talking about books and other things. Afterwards, she records le Carré saying:

“Your friend smiled and joked but did you notice it never reached his eyes? … I fear he will be rubbed out. There’s a darkness gathering over him.”

However, because Do Not Disturb focuses on the dark side of the Rwandan moon it departs dramatically from fairly familiar paths of official history. First of all, Wrong documents the RPF’s own often arbitrary violence against Hutu people during their march on Kigali in 1994; second, she shows how in both Rwanda and then in wars in neighbouring Zaire/DRC the RPF (with Kagame as orchestrator) played a much more instrumental role in mass murder and mayhem than the official narrative allows.

Finally, she focuses extensively on the brutal and intolerant means by which Kagame secured the consolidation of his own power after he became the President of Rwanda in April 2000, and the ways in which the myth of developmental “poster child” Rwanda was cultivated. In her words, Kagame “perfectly calibrated Western donors’ need to be needed” resulting in “philanthropic foundations set up by the world’s most influential retirees ador[ing] his regime”.

Ironically, given the accusations of racism levelled against her by the book’s detractors, she quotes historian Gérard Prunier as regarding Western tolerance of Kagame’s dark side as “a lingering form of racism, in which violence is seen by the international community as ‘normal for Africa’, and a firm hand on the tiller a necessary corrective to keep barely civilised inhabitants in control.”

Finally, a thread that runs throughout the book — exemplified by Karegeya’s and other murders — is how security and surveillance networks set up by Kagame have tentacles that can reach and strike across Africa and in Europe. For such a small country its security apparatus is remarkably sophisticated, and not for nothing does Wrong sometimes compare it with Israel’s Mossad.

So when I asked for more detail about responses to the book’s publication I was not surprised by the answer.

Had she been threatened directly?

“Not physically”, she says, but notes that, “there was unadulterated fury and vitriol even before the book was published. There has been pretty much a constant tide of personal abuse even before the book came out.”

She has been called variously “a racist, Karegeya’s mistress, Museveni’s lover, in the pay of the French military, a paid scribe for Ugandan intelligence, etc etc etc”.

Attempts have even been made, via a public petition, to have her “no platformed” from a book launch at the Royal African Society “because I was a well-known racist”.

“It was the first time it happened to me… but it didn’t work. The number of signatures is pretty pitiful.”

Some of these responses were predictable. She says that the “she’s a racist” abuse came first from opinion pieces in Rwanda’s New Times newspaper (a government mouthpiece, although nominally privately owned), magazines dependent on Rwandan government advertising, Rwandan blogs by well-known Kagame loyalists, Twitter accounts known to be run by Rwandan intelligence, and reviews by Western academics/researchers whose admiration for Kagame’s style of authoritarian rule is no mystery (she names Linda Melvern, Prof Phil Clark, Jos Van Oijen). In her words “all part of a very efficient state propaganda campaign”. (Please note responses from Melvern, Clark and Van Oijen at the end of the article)

But Wrong expresses disappointment at a string of publications in Africa that she feels should have been more objective:

“Kagame’s style of repressive rule presents Africa with a fundamental challenge. If these journals and magazines aren’t going to stand up for African citizens’ rights, then who is?”

I prod her for names and she mentions several titles (see here and here) including African Business, whose June 2021 edition commissioned a review, but then felt the need to add an unusual (and I would add slavish) rebuttal of sorts. Titled “Note by the publisher” it offers a kind of mea culpa for the positive review, balancing it with quotes from a number of critical reviews and commenting that:

“Often, with Western perspectives, the context is lost. And situations are often much more complex with many underlying forces at play. African Business believes in Africa’s future.”

Yet the book has ample and well-referenced historical and contemporary context and Wrong says she too believes in Africa’s future. But she concedes that she can understand the “wave of irritation with white writers who dare to comment on African affairs — I completely sympathise with that”. But, she adds, “if you look at the current climate of intolerance it’s almost impossible for African journalists to honestly report on their own continent without risking going to jail, being beaten up or even being killed. So it does end up being people like me, who live safely in the West, commenting, and it’s obviously very irritating to see a white, middle-class Western woman opining on African regimes.”

Judging by the reports of attacks on journalists by the Committee to Protect Journalists, Wrong is not wrong when she draws attention to the threats to journalists in many countries of Africa.

Yet despite the Kigali-sponsored battery to stigmatise the book, Wrong says she’s been “intrigued and heartened” by many of the personal responses to Do Not Disturb.

“An enormous number of people have contacted me privately via my website, many of them people who have lived or worked in Rwanda, saying ‘Finally! I always felt there was something wrong, but the consensus was such that I never felt I could say anything, so I kept quiet’. That’s come from a lot of people in the NGO sector or the development world.”

She feels Do Not Disturb, and a few other publications — such as Judi Rever’s In Praise of Blood — with the “steady drip, drip, drip of human rights revelations” have contributed to a “tipping point” being reached regarding perceptions of Kagame and his regime: “the book played a part in a process of reevaluation that was already under way” nudging the narrative away from “marvellous, plucky little Rwanda”.

This brings our conversation back to South Africa, which plays a significant part in Do Not Disturb: as a place of exile, as a regional power that brokered negotiations between warring parties in the Great Lakes, as the site of murder and attempted murders and eventually the inquest into Karegeya’s killing.

Wrong seems to have a soft spot for us but she criticises SA for “not leading” in Africa, saying that Kagame has browbeaten South Africa’s presidents and that former President Zuma, in particular, seemed to be “utterly cowed by him”.

“It took an awful lot of repeated attacks on Rwandan exiles in South Africa before any diplomats were expelled. The role of the embassy was very obvious to everyone … The inquest was delayed for five years for political reasons, the Hawks knew who was responsible, Parliament knew, SA knew exactly what was going on but never made the right amount of noise … and so Kagame continues to behave in that way.

“And Rwanda’s officials still are. The Rwandan diplomats who once worked in South Africa are now stationed at the High Commission in Mozambique, where they are rounding up and renditioning Rwandan dissidents.

“You should be the moral arbiters of Africa, but instead appear intimidated by this president just because he’s more aggressive than you are. In terms of moral leadership, SA should be doing much more.”

Who’s wrong?

So what should we think of Do Not Disturb: “racist” and stereotyping Africa, or a journalist being faithful to the ethic to uncover truth and then blast it back at power?

For me, there is no doubt.

Do Not Disturb is certainly partisan and draws heavily on interviews with those who have fallen foul of Paul Kagame. But it is carefully researched and referenced, meticulously piecing together disparate pieces of history. Her claims of the RPF’s deep involvement in crimes against humanity, murder and intimidation are not speculative or imagined, but come from official reports and sources, which survive in the historical archive despite attempts to bury or downplay them.

There was bound to be an organised attempt to discredit Do Not Disturb and it was never going to be a polite one. Put simply, if you couldn’t kill the author then you’d better try to kill the book — and claiming racism is one sure way to cancel buyers and readers.

But in my view that’s bollocks.

This book is essential reading for 21st-century human rights and social justice activists, politicians (especially those who direct our foreign policy and trade) as well as for the public at large. It’s a “don’t miss” for all those who want to understand what went wrong with many of the world’s liberation movements and how, whether their leaders be Daniel Ortega, Paul Kagame or Jacob Zuma, they will use any means necessary to hold on to power. Read it. DM/MC

Maverick Citizen has received complaints from three of the persons named by respected British writer, Michela Wrong, in an interview with Mark Heywood concerning her new book, Do Not Disturb, the Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad. We reprint them below.

In your article of 18 July, “Writing Large: An interview with Michela Wrong, author of ‘Do Not Disturb’,” you refer to me as having published a review of this book and of taking part in “a state propaganda campaign”. I would like to inform you that I haven’t published a review, not yet at least, so it’s rather premature to dismiss it as propaganda and call me a Kagame admirer (I’m not, where’s the evidence for that?).

This may surprise you, but there is a middle ground between admiring Wrong and admiring Kagame. This middle ground is populated by people like me who look at the quality of the facts. What do the facts tell us? A critical analysis of the book’s content reveals that about 60% qualifies as proper journalism, but the remaining 40% contains recycled myths and errors, even a few inventions.

I’m not critical of Wrong’s endeavour but of her method. Like so many contemporary journalists, Wrong relies on her intuition when she decides which stories to believe, which informants to trust, who to like, who to dislike, where the truth lies. As we can tell from the many factual mistakes in the book, that’s a very risky method,

Every story has facts, and facts can be checked. Every journalist ought to know that. Some of the errors should have us all concerned. Wrong recycles a few stories that were introduced back in May and June 1994 on the Rwandan hate radio stations. Anyone – me, Wrong, you – can check the source material. Those stories are not even realistic when you look at them from a technical or scientific perspective and some have been refuted by specialists years ago. Why do we keep encountering them as if they’re revelations?

Is anyone who points at these flaws automatically part of a state sponsored propaganda campaign? Please. A little more research and a less polarizing attitude would be advisable here. Michela should own her mistakes, deal with them, and stop shooting at the messengers.

Sincerely, Jos van Oijen.

In response to our offer that he publish a response to the substantive issues in the book Mr van Oijen replied: “The burden of proof lies with you – I’m insulted without reason or substantiation. You can publish my response or make a public apology. If you want an in-depth discussion of the errors in the book, I would have to cover 200 of the 470 pages. Not really doable.”

*****

I am a British investigative reporter and I have written seven books of non-fiction. I have a careeer in journalsim that spans more than fifty years, including as a member of the Sunday Times Insight team. In his review of the Michela Wrong book Mark Heywood repeats without question a claim by Ms Wrong that I am part of “a very efficient state sponsored propaganda machine”. This is both ludicrous and defamatary. If you care about defending the truth then you will issue an immediate apology, Linda Melvern

Maverick Citizen offered Ms Melvern the opportunity to respond to the substantive issues in the book. She responded “Thank you for your swift response to my request for an immediate correction and apology. The statement made Ms Michela Wrong that I am part of “a very efficient state sponsored propaganda machine” is clearly defamatory. The wording of your correction and apology is a matter for your corrections editor.

I would be happy to write an article at some later stage. I refer you to my website lindamelvern.com.

*****

To the editor –

Mark Heywood’s 18 July article, “Writing Large: An interview with Michela Wrong, author of ‘Do Not Disturb’”, repeats two defamatory statements that Wrong makes about me in her interview. Contrary to Wrong’s claim, I have never called her a “racist” and my recent review of her book in Foreign Affairs was not “part of a very efficient [Rwandan] state propaganda campaign”. My review – which draws on 20 years of independent academic research on Rwanda – highlights various strengths of Do Not Disturb, including its portrayal of the Rwandan government’s extraterritorial violence against dissidents, as well as the book’s shortcomings.

It is unfortunate that Wrong has chosen to denigrate all of her critics as being on the Kigali payroll rather than engaging with the substance of their critiques. This fits a growing trend in debates about Rwanda – to lambast different sides as either “genocide deniers” or “Kagame acolytes”. In her book, Wrong identifies this kind of polarisation as a barrier to meaningful debate but, in blanketly pillorying her critics, she exacerbates rather than diminishes this problem.

Two recurring themes emerge from the critical reviews of Do Not Disturb, which Wrong is reluctant to address. First, the central argument of her opening chapter is that all Rwandans are liars, there is a “Tutsi knack for secrecy”, and duplicity is ingrained in Rwandan culture – “a culture that glories in its impenetrability, that sees virtue in misleading”. In my review, I describe this as perpetuating an Orientalist strand of commentary on Rwanda that has persisted since the Belgian colonial period. Understandably, Rwandan commentators such as Vincent Gasana, Gatete Nyiringabo Ruhumuliza and Shyaka Kanuma have criticised this depiction of the entire Rwandan population. While Wrong now refuses to engage directly with her own claims about Rwandan culture, she has reproduced her chapter on this theme as an online article entitled, “The Virtue of Lying? Unmasking the Truth about the Rwandan Genocide” – which Daily Maverick readers can digest and make up their own minds.

Second, as I highlight in my Foreign Affairs review, while raising legitimate concerns about the Rwandan government’s violence abroad, Wrong romanticises Kagame’s opponents such as the Rwanda National Congress (RNC), whose assassinated leader Patrick Karegeya is the central figure in her book. Wrong skims over the crimes that Karegeya, former head of Rwandan military intelligence, and other RNC leaders committed as senior figures in Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). She also skirts around the RNC’s current attempts to use military force to topple the government in Kigali, as highlighted in several United Nations reports since 2018. That South Africa has been used as a launching pad for the RNC’s plans for armed overthrow continues to bedevil relations between South Africa and Rwanda – but receives scant mention in Do Not Disturb. Wrong’s narrow good guys/bad guys account frames groups such as the RNC as inherently peaceful and democratic by dint of their opposition to Kagame and the RPF, belying the RNC’s history and its stated military objectives today.

Wrong’s defamatory comments about her critics are an attempt to avoid scrutiny of these troubling claims in her book. Her remarks cause significant professional harm to those named commentators. More importantly, her personal attacks stymie civil debate, leading to further polarisation and simplification in discussions about post-genocide Rwanda.

Phil Clark, Professor of International Politics, SOAS University of London

Maverick Citizen has drawn the responses to the attention of Michela Wrong.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.