TRIBUTE

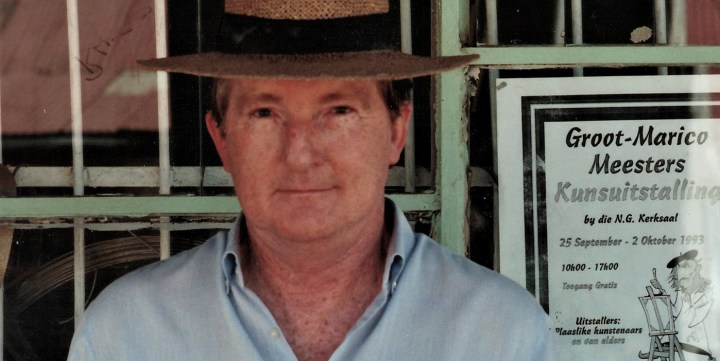

A Picture of Stephen Gray, always writing: 1941-2020

In an attempt to understand on whose literary shoulders he stood, Stephen became one of the greatest champions of South African classics and reignited an interest in the work of writers such as Olive Schreiner, Sol Plaatje and William Plomer.

Anthony Akerman

Thirty years ago Stephen Gray thought he was going to die. In the early hours of Sunday 21 October 1990, he was in bed reading when three intruders gained access to his home. A knife was held to his throat and he was tied up.

They wanted money, his rented television set and his car. He recognised and greeted one of them, then realised his mistake. Now they’d have to kill him. He was going to be stabbed to death the way the writer Richard Rive had been the year before. When he told me this story, he said Richard helped him survive. He kept thinking, “What did Richard do that I mustn’t do?”

Potential tragedy segued into farce when the car thieves – who were unable to drive – pushed his Citi Golf into the path of an oncoming police patrol on Sixth Avenue, Mayfair. He was spared another 30 years and one day and died on 22 October 2020 of prostate cancer.

Stephen was born in Cape Town in 1941. His father, the taciturn Ginger Gray, was up north and so, as a war child, he spent his formative years with his protective mother. He was sent to St Andrew’s College, Grahamstown, did his first degree at the University of Cape Town, and then went to Cambridge, his father’s alma mater, to read for a science degree, but switched mid-stream to the arts.

He lived away from South Africa for seven years, teaching in France, doing a postgraduate creative writing course at the University of Iowa, and always writing. When he returned, he took up a post in the English Department of the new Rand Afrikaans University, where he completed his doctoral thesis and became Professor of English.

I first became aware of Stephen through the anthologies of South African plays he compiled and edited. He also edited the Southern African Literature Series on Athol Fugard, which interested me as I directed several Fugard plays in Dutch while living in Amsterdam. I knew he’d rescued the manuscript of a forgotten novel called Tsotsi from a box in the National English Literary Museum (NELM, now Amazwi) and had persuaded Fugard and Ad Donker it was worth publishing.

Without Stephen’s literary detective work and persistence, South Africa still wouldn’t have an Oscar for Best Foreign Film. By the 1970s, South African writing in English had found a local market and no longer needed to be written for export. In an attempt to understand on whose literary shoulders he stood, Stephen became one of the greatest champions of South African classics and reignited an interest in the work of writers such as Olive Schreiner, Sol Plaatje and William Plomer.

I first met him at the bar of the Windybrow Theatre in 1991. He told me he was compiling an anthology of South African plays for Nick Hern Books in London and wanted permission to include my play Somewhere on the Border. After being away from South Africa for nearly two decades, his offer felt like an inclusive embrace.

Being published alongside Maishe Maponya, Sue Pam-Grant, Paul Slabolepszy and Pieter-Dirk Uys was a real homecoming. In our subsequent interactions I benefited from Stephen’s generosity, encouragement and friendship. I’m one of many writers, academics and former students of his who owe him a debt of gratitude.

A week after we met I was invited to lunch in Mayfair. Stephen only invited guests on days when Bella Mtimkulu was there to do the cooking. Mayfair was one of the first “grey areas” that became racially integrated during apartheid and that made living there appealing to people like Stephen. However, he’d recently been told the house he owned was the birthplace of FW de Klerk. De Klerk’s grandfather had been the local dominee and, according to Stephen, the “whole clan” had lived there.

He was increasingly irritated by prying television crews crawling around to film the birthplace of the president who’d promised to dismantle apartheid. Several years later, Mayfair hit the skids and Stephen moved to Killarney just before the bottom fell out of the housing market.

I went on several literary excursions with Stephen, usually to take photographs for his articles, and I was always entertained by his anecdotes and literary gossip. In 1993, on the way back from the first meeting of the Herman Charles Bosman Literary Society in Groot Marico, Stephen told me about the South African actress Marda Vanne who’d married the future Prime Minister JG Strijdom. She was lesbian and left him for the actress Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies.

Stephen maintained Strijdom wasn’t heartbroken because he himself was gay. He spoke about Noel Langley, son of the tyrannical AS Langley, who’d been headmaster of Durban High School (DHS) and the poet Roy Campbell’s nemesis. Noel, a playwright and novelist, had written the screenplay for The Wizard of Oz and his letters from Hollywood to his mother are preserved in Durban’s Killie Campbell Africana Library.

Stephen always had something of interest to show you. In 2002, he and Craig MacKenzie went to the National Arts Festival to launch the latest Anniversary Editions of Herman Charles Bosman’s work which they’d co-edited. I was delivering a paper at Wordfest, so we met outside Bloemfontein and drove in convoy.

Our first stop was Philippolis where he wanted to see the new Memorial Garden containing Laurens van der Post’s ashes. He turned off at Trompsburg and then made an unexpected detour. I pulled up next to him to find out what the problem was. He pointed to a house. What? That was where the reclusive Karel Schoeman lived and wrote his masterpieces. Then he took off at speed. We visited the home where Van der Post grew up and had lunch in the new centre where a writers’ retreat was being built. This was before we’d read JDF Jones’s Storyteller and discovered what a fraud Prince Charles’s godfather had really been. Driving back from the last lunch we had together, Stephen insisted I turn up an unfamiliar road in Parkview. What were we doing there? “That house over there,” said Stephen, “is where Nicholas Monsarrat wrote The Cruel Sea in 1951.”

Stephen didn’t do computers or cell phones. What seemed like antediluvian posturing was both a source of amusement and frustration to his friends. What would happen if his car broke down at night and he didn’t have a cell phone? Stephen was unmoved by such arguments. He had an answering machine, for God’s sake, so leave it alone! I had noticed, however, that he was writing his autobiography, Accident of Birth, using a Brother CE-70 electronic typewriter with interchangeable daisy wheels. When he bought it, he was way ahead of the technological curve. Writing his autobiography was a spin-off from the therapy sessions he realised he needed after his near-death experience. I suspect few of his friends – myself included – understood how profoundly life-changing that trauma had been. He decided the 1993 Penguin Book of Contemporary South African Short Stories would be the last anthology he’d edit.

He took early retirement, supplemented his pension by contributing articles and reviews to the Weekly Mail (later the Mail & Guardian) and devoted the rest of his time to his literary output. When he returned the television to the rental company, he might have seen it as a symbolic parting of ways with technology. Anyway, whenever he had to send an email to, say, Rose Moss in America, he could always drive around to my house and get me to do it for him.

After that first lunch I sat in Stephen’s book-lined lounge admiring his posters and the framed copies of books he’d written and edited. He asked me about myself and I spoke about returning from exile, having been adopted and meeting my birth mother for the first time at the age of 40. He stopped me in mid-flow, told me it was a book and that I should write it. He was insistent, but I felt it was too soon.

When we last had lunch together, 28 years later, I told him I’d almost finished Lucky Bastard, the memoir he’d urged me to write, and he said he was pleased I’d finally taken his advice. In recent years we saw each other infrequently, but he was a presence in my life and I know I’ll always expect to bump into him somewhere, perhaps coming out of Cinema Nouveau. What had he just seen? “Hadn’t you heard about the Croatian Film Festival, Anthony?” No, I hadn’t, Stephen and, now that you’re no longer here, who the hell’s going to tell me about things like that? DM

Anthony Akerman (1949) is a playwright who also writes radio and television drama. His plays include the award-winning Somewhere on the Border, Dark Outsider and Old Boys. He has just completed Lucky Bastard, a memoir that chiefly tells his adoption story.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Beautiful article.

Correction: Prince William’s godfather. Lord Mountbatten was the godfather of Prince Charles!

Re my previous comment: Laurens van der Post was Prince William’s godfather.