BUSINESS MAVERICK ANALYSIS

Prohibition: Social conservatism that’s shattering working-class lives

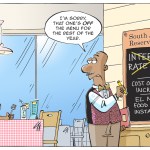

The consequences of prohibition include mounting commercial casualties that have helped land South Africa’s economy in the trauma unit. The motives of some of its backers are well meaning, and the reasoning behind the ban not without its merits. But as the economic toll mounts, it is worth bearing in mind that it reflects a socially conservative agenda with racist and classist roots, and that the working class is ultimately paying the price.

In Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale and its sequel The Testaments, the brutal Christian theocracy of Gilead imposes alcohol prohibition as part of its rigid and biblically inspired moral code. But the rulers and elite, of course, imbibe behind closed doors.

In Atwood’s original rendering, Gilead was more overtly racist than its portrayal in the riveting Hulu series inspired by the novel. That speaks to a broader point: Prohibition as a policy not only goes hand in hand with patriarchy and homophobia in theocracies, it has also historically fit snugly like a sjambok into the iron fist of a socially conservative state, as well one that wants to keep a leash on the underclass.

In short, it is the policy of a government that does not trust its own people. Such governments often fail to comprehend that distrust is reciprocal.

As one example of many, take South Africa’s mining industry.

In the late 19th century, the Chamber of Mines initially encouraged the black migrant labour force to drink. The view was that if wages were spent this way, the miners would renew their contracts. But the impact of often excessive drinking on productivity eventually put paid to that notion. By 1896, the Chamber of Mines was advocating total prohibition on the sale of alcohol to black people in mining areas.

The following year, a law came into force prohibiting any black person on the Witwatersrand from buying, selling or drinking liquor. Variations of that 1897 law would subsequently be refined, effectively making it illegal under apartheid for black South Africans to consume anything, with rare exceptions, but traditional sorghum beer.

These are among the roots of prohibition in South Africa, making the 19th century Chamber of Mines and its colonial political allies the historical handmaidens of South Africa’s current batch of prohibitionists.

Beware the historical company you keep. Past temperance traditions elsewhere, such as in North America, also targeted racial or ethnic groups or the poorer classes. They also often have a distinctly religious bent. In the US “Bible Belt”, if you live in a county or district that is “dry” or “not so wet”, that is usually thanks to the efforts of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). The SBC is also America’s largest Protestant denomination and a key, and staunchly conservative, base of political support for the Republican Party. The face of that party right now is also the far from religious, but overtly racist and teetotalling Donald Trump.

There are also African traditions of prohibition which clearly could not be construed as racist. The respected commentator Anthony Butler, among others, has made the telling observation that in deeply religious South Africa, a ban on alcohol sales has wide support, a point not lost on the governing ANC.

The millions of members of the Zion Christian Church (ZCC) were initially supposed to refrain from alcohol, and South African soil has proven to be fertile for the growth of various evangelical brands of Christianity which preach temperance. This can be seen across the African continent, which has fast-growing flocks of both evangelical Christianity and Islam. The crescent and the cross can both take dim views of booze.

And undoubtedly, South Africa is in many ways a “socially conservative” country – to the extent that it could possibly be argued that its admirably progressive Constitution does not always reflect wider popular values.

Yet, that is a slippery slope, as many of those who frown on alcohol consumption on religious grounds also oppose gay marriage or regard gender equality as an affront to their values. Throwing red meat to that base can set a dangerous precedent.

Of course, the reasons given for the current ban on alcohol – and its twin ban on tobacco products – are related to the unprecedented health crisis that is the Covid-19 pandemic. The main justification is to free up (relatively scarce) healthcare resources for the battle – most urgently, to relieve trauma units already overwhelmed by Covid-19 from the additional strain of cases related to alcohol-induced violence or accidents. That sounds reasonable.

But even scientific advisers to the government such as Dr Glenda Gray of the Medical Research Council have suggested other options, including curbs on the amounts that consumers can buy. Other sensible recommendations include maintaining the curfew to ensure people are not drinking and driving late at night, when many of the booze-related incidents that require hospitalisation occur.

Only someone who has spent decades in a blue-light brigade bubble, with an immensely inflated sense of their own self-importance and influence on public behaviour, could possibly believe that prohibition would be an effective policy. But then, governments that don’t trust their own people are also usually out of touch.

And it must be said that the fact that South Africa has had to take this drastic action – replete with its sinister history and undertones – is surely a reflection of utter governance failure. Put another way: The healthcare system might have been better prepared if, say, R200-million had not been blown on the fire pool and other such nonsense at Nkandla, the residence of a teetotaller just by the way. Not to mention the hundreds of billions of rand looted, siphoned and squandered under the watch of said teetotaller.

Another issue is the effectiveness of prohibition, especially against the backdrop of a corrupted state robbed of much of its capacity under the giggling teetotaller. Prohibition actually never works: Colonial and apartheid efforts gave rise to the shebeen, while in North America, the experiment in the 1920s is widely regarded as a spectacular flop that facilitated the rise of organised crime.

In the 2020 South African version, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that households are still able to stock up on liquid assets, especially the elite – as in The Handmaid’s Tale, the rules hardly apply here, especially if you are fortunate enough to still have a disposable income.

Only someone who has spent decades in a blue-light brigade bubble, with an immensely inflated sense of their own self-importance and influence on public behaviour, could possibly believe that prohibition would be an effective policy. But then, governments that don’t trust their own people are also usually out of touch.

That is not to say that South African society does not have a “drinking problem”. Gender-based violence is also a serious and disturbing scourge in South Africa, and much of this is fueled by alcohol. Many women, from townships to affluent suburbs, no doubt support prohibition for perfectly understandable reasons, and it would be revealing to see a survey or studies on the matter regarding the current ban based on gender.

But alcohol alone does not make a physically abusive misogynist. Such views ferment in the bottle of social conservatism, with its typically unyielding take on gender roles, and flow in dangerous directions when they are uncorked, with or without alcohol. Remember, Trump is a teetotaller. That does not inhibit him from bragging about grabbing women by the you-know-what.

Then, there is the loss of investment. President Cyril Ramaphosa has staked much of his reputation on pledges to boost South Africa’s investment levels. But the bans have now directly cost the economy promised investment. South African Breweries has halted plans to spend R5-billion on plant upgrades while Heineken has ceased work on a R6-billion brewery. And glass maker Consol has suspended construction of a R1.5-billion plant in South Africa.

Former President Jacob Zuma is also a teetotaller and the rape trial in which he was acquitted provoked public displays of terrifying misogyny from many of his supporters. Alcohol is not always required to stir up masculinity in its most toxic forms.

For tobacco, the case is clear cut: The ban is not working and is, in fact, undermining its stated goals.

A recent study by UCT’s world-renowned Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) found that 93% of smokers were still obtaining their fix, but prices on the black market had soared 250%. It also found that over four times as many people were now sharing smokes, making a mockery of Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma’s claim that the ban would discourage people from “sharing zol”. (Remember: The blue-light bubble removes you from social realities).

The study further found prohibitive prices were the main reason people sought to quit.

In its court filings recently, urging the lifting of the ban, British American Tobacco South Africa (BATSA) made the devastating point that “… the government has not prohibited the sale of cold drinks merely because they are capable of being shared from the same bottle or can; it has rather educated consumers not to share bottles or cans”.

On that front, it is worth noting that sugary drinks are also a health risk given the links between Covid-19 morbidity and obesity. Why has Coca-Cola not been banned?

“What makes the minister’s justification even more perplexing is that, in the current version of the Regulations, she has permitted minibus taxis to carry passengers at 100% of licensed capacity for short-haul journeys. The risk of the public health system being overwhelmed is much greater if commuters sit cheek by jowl in taxis than if smokers are permitted to continue smoking,” BATSA also said in its filing, effectively eviscerating Dlamini Zuma’s stance.

UCT’s REEP unit made the sensible suggestion that the ban be immediately lifted, with a sharp increase in the excise tax, from the current level of R17.40 per pack of 20 cigarettes to R50 per pack or more. Smoking is terrible and has huge health, social and economic costs, and this would be the most effective way to curb the consumption of tobacco.

Hiking the excise tax for both tobacco and booze – which Business Maverick recommended back in May 2020 – would also bring South Africa more in line with international standards.

Compared to Europe, North America and other regions, booze and smokes remain astonishingly cheap in South Africa. This, by the way, is a competitive advantage on the tourism front. It also highlights a wider political issue. There is a reason why the National Treasury, when it marginally hikes sin taxes each February in the Finance Minister’s budget speech, usually leaves “African beer” alone. Yes, the ZCC and other non-drinkers are part of the ANC’s political base. But that base also includes consumers of African beer, which has long traditions bound up in rural culture.

The tax issue brings us to the economic damage wrought by prohibition. And the numbers are sobering.

The revenue loss to SARS and the Treasury to date from the twin bans has also been substantial, at a time when South Africa has had to borrow around R70-billion from the International Monetary Fund. South African Breweries has said that R12-billion has been lost in excise tax from the alcohol moratorium. For tobacco, it has been around R35-million a day, so close to R5-billion to date. This at a time when South Africa’s debt levels are soaring as the economy craters. The fiscal imperatives for lifting the bans and simultaneously raising the sin taxes are gin-clear.

Then, there are the wider economic knock-on effects which some ministers clearly did not consider, betraying their ignorance of the complexities of a relatively advanced economy.

Most of the people who derive an income along the alcohol and tobacco value chains are also working-class, and many will have several dependents. Their livelihoods are now being shattered at a time when the unemployment rate has been surging from 30% in the first quarter of 2020.

Agri SA says in a statement that it “is gravely concerned about the impact of the current alcohol ban on the entire alcohol value chain stretching from wine, barley, hops, fruit and maize farmers to glass manufacturers and processors”. Barley, produced mostly in the Southern Cape, will be harvested late in the year and farmers have no idea if they will have buyers. Agri SA also says that the wine industry has lost R3.3-billion in sales revenue and that more than 800 small alcohol manufacturers are facing bankruptcy. Tobacco farmers, including emerging farmers with women among their ranks, are also staring at collapse.

Then, there is the loss of investment. President Cyril Ramaphosa has staked much of his reputation on pledges to boost South Africa’s investment levels. But the bans have now directly cost the economy promised investment. South African Breweries has halted plans to spend R5-billion on plant upgrades while Heineken has ceased work on a R6-billion brewery. And glass maker Consol has suspended construction of a R1.5-billion plant in South Africa.

So that is over R13-billion in planned investments – and thousands of jobs – that have been put on ice. And that may just be the tip of the iceberg. What major brewer or distiller in the future will commit scarce capital to a project in South Africa, knowing that prohibition is now part of the political risk profile? Untold billions of rands in investments down the road have also gone up in smoke thanks to this ham-fisted policy.

And curiously, in the face of a draconian prohibition regime, the Cabinet has approved the “Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill” and sent it to Parliament. This is supposed to give effect to the Constitutional Court judgment of two years ago, which held that prohibitions on cannabis for personal use were unconstitutional. But South Africa’s embrace of alcohol and tobacco prohibition will also give prospective cannabis investors serious pause for thought.

Then, there is the unfolding impact on bars and restaurants – a sector of the economy which is labour-intensive. Agri SA says 117,000 jobs have been lost in the wine industry. The carnage in the restaurant and bar sector may also approach 100,000 jobs or more. SAB, in the statement in which it announced it was pulling the investment plug, noted that the alcohol value chain “impacts over one million livelihoods across the country”. Jobs are also on the line in the tobacco sector.

Most of the people who derive an income along the alcohol and tobacco value chains are also working-class, and many will have several dependents. Their livelihoods are now being shattered at a time when the unemployment rate has been surging from 30% in the first quarter of 2020.

The working class is often the target of socially conservative policy initiatives. In this case, they are also its main victims. Given prohibition’s racist and classist history, that should perhaps come as no surprise. DM/BM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider