South Africa

RSA in a dewdrop: Reflections on the political murder trial of the decade

In South Africa, like pretty much everywhere else in the known universe, the more things change the more they stay the same. The Nokuthula Simelane murder trial is testament to this truth. Because if it’s obvious that PW Botha’s security forces murdered MK operative Nokuthula Simelane in 1983, why are the NPA now acting as if they’re paid by the accused? Why have the NPA not indicted the Security Branch brigadier who gave the order for Simelane’s abduction? Why is police minister Nkosinathi Nhleko being so bloody rude? And why, even today, is “apartheid mole” the worst insult you can throw at an ANC heavy? KEVIN BLOOM considers these age-old questions in light of recent developments.

“If we now arbitrarily select one of these jewels for inspection and look closely at it, we will discover that in its polished surface there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number.”

An exercise: let’s take this third-century Buddhist text at its word, and arbitrarily select for inspection the jewel (ugly though it is) known as “The Nokuthula Simelane Murder Trial”. Let’s remind ourselves that before January 2016, when four former members of the Security Branch were charged with her murder, the jewel was known as “The Nokuthula Simelane Unresolved Case”, and so was much more opaque than it is today. Let’s be clear, before we begin to explore the jewel’s reflections, that our objective with this exercise is not to simply join the dots between a series of recent (apparently random) events in the 34-year-old saga, but to show how these events reverberate across multiple dimensions in South African space and time. Lastly, let’s acknowledge the absurd hubris of our ambition, and state that it will remain the reader’s prerogative not to take any of the ensuing points seriously, but that if the reader does view the Simelane saga as more than just a sideshow—we are talking, after all, about the ONLY apartheid-era political murder trial to take place in the country in the last decade—he or she is invited to stick around at least until he/she can tell us why we’re full of crap.

Anyway, confining our exercise to the year 2017, the core event happened on 6 February, when an elderly gentleman by the name of Kid Sigovu disrupted a media briefing held at Luthuli House by leaders of the Umkhonto we Sizwe Military Veterans Association (MKMVA). According to reports (see here, here and here), Sigovu pushed to the front of the hall, sat down beside some journalists, and waited for former South African National Defence Force chief Siphiwe Nyanda to speak. When Nyanda began, Sigovu stood up and shouted this:

“You have never held a press conference about Comrade Simelane! She disappeared after you seconded us to come fight inside the country! I was also arrested, you never called all of us into a meeting! This woman was killed! Why are you here today?”

Before he could finish, Sigovu was escorted forcefully to the exit. Out on the pavement that encircles Luthuli House, he filled in the blanks for reporters. “During that time, people were paid by the apartheid regime and that is why they are rich today! They were paid! We went to Robben Island because they were paid! Who sold out this woman?”

For those who were familiar with the case, these words—in this context—would have opened a wormhole into at least another five reflections on the core jewel, and at the door of each reflection would have been a question/set of questions.

Reflection I

Why must the family of someone brutally tortured and forcibly disappeared go to court to compel the police to pay the legal fees of the alleged killers?

At the same moment that Sigovu was disrupting the MKMVA press briefing in downtown Johannesburg, out in the suburbs there were lawyers preparing an “Intervention Notice” on behalf of Thembi Nkadimeng, the executive mayor of Polokwane, and the woman who had been chasing her sister Nokuthula’s killers for more than thirty years. What was the notice about? All was revealed in item 3 of the application, which asked the court to compel “the [Minister of Police] and/or the [provincial commissioner for Gauteng, South African Police Service] to pay the reasonable legal defence costs of accused two to four in the criminal matter of The State v MT Radebe and 3 Others.”

In other words, as the Daily Maverick reported in September 2016, SAPS were refusing to pay the legal costs of former Security Branch members Willem Coetzee, Anton Pretorius and Frederick Mong—and Mayor Nkadimeng, rather than wait another God-knows-how-long for a ruling from a sub-trial, had decided to force their hand.

But here was the remarkable thing: SAPS weren’t refusing to pay the legal costs of the accused because they were arguing that there was no continuity between themselves and the apartheid police (such an argument is inadmissible in local and international law), they were refusing to pay because of their belief that the accused were off on a private frolic.

In other other words, SAPS were arguing that abduction, torture and murder were inconsistent, at least notionally, with official police procedure under apartheid.

Reflection II

Why did the National Prosecuting Authority not put up any vigorous opposition to the long postponement? Why were they happy to sit on their hands? Is such conduct not consistent with the long neglect this case has suffered? More particularly, is it not consistent with the unwritten policy of the state to kill off the so-called political cases of the past?

Which are in effect the most explosive questions—the questions, as the Daily Maverick reported in a series of articles on the Simelane trial in 2016 (see here and here), that possibly cost former national director of public prosecutions, Vusi Pikoli, his job.

The background goes like this. In the last few years of Thabo Mbeki’s grip on power, a coterie of ANC heavies—including Brigitte Mabandla, Zola Skweyiya, Thoko Didiza and Jackie Selebi—advised Pikoli that if he thought part of his duty was to prosecute former members of PW Botha’s hit squads, he thought wrong. Pikoli, who was taking his cue from an act of parliament (the TRC Act, to be precise), chose to ignore this advice. He cajoled, he stalled, he eventually asked why? He was told, according to an affidavit submitted to the Ginwala Commission in 2008, that such men, especially if they were hit squad commanders, might say things under oath about the ANC that the new democratic government did not want said.

All of the chief public prosecutors that came after Pikoli appeared to get this message, as explained by a) the fact that the Simelane case is the first apartheid-era political murder trial to come before a South African court since 2007, and b) the fact that Nkadimeng had to approach the High Court before Shaun Abrahams, the current chief public prosecutor, would deliver the indictment to the four accused.

In the supporting affidavit of Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza attached to the abovementioned Intervention Notice, which was submitted to the Pretoria High Court in mid-February 2017, paragraph 37 read as follows:

“I have frequently gone on record stating that there has been a disgraceful lack of political will to deal with the issue of accountability for the apartheid-era victims of gross human rights violations. I fully endorse Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s statement made in 2013 that the failure to prosecute those who failed to apply for amnesty undermined those who did.”

Reflection III

Why did the Minister of Police ignore the pleas from the family to cover the legal costs of the accused? Why not even an acknowledgment? Was it for the same reasons as the above?

In Thembi Nkadimeng’s own founding affidavit attached to the Intervention Notice, she noted in paragraph 38 that she requested her attorney, Moray Hathorn, to approach the police minister to urge him to pay the reasonable legal costs of the criminal defence of the accused. This letter, she testified, was sent to Minister Nkosinathi Nhleko on 15 September 2016.

Hathorn advised Nhleko in the letter that the litigation over legal costs “could potentially delay the start of the trial for a considerable period of time, perhaps a year or longer”, and that the family, who’d been struggling for closure for more than three decades, “strenuously objected to the delay.”

Hathorn also submitted, at some length, that Coetzee, Pretorius and Mong were indeed acting in the course and scope of their duty when they abducted, tortured and allegedly murdered Simelane in 1983. He cited the Goldstone Commission and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which had both concluded that “the Security Branch was in large part a criminal enterprise aimed at neutralising the threat to the apartheid state.” He also cited the testimony of former commanding officers of the Security Branch, who’d admitted under oath that the organisation acted unlawfully on a routine basis.

Minister Nhleko did not acknowledge receipt of the letter.

Reflection IV

Is SAPS seriously contending that the apartheid state had neither knowledge nor control when it came to the crimes committed by the security forces?

In the supporting affidavits to the Intervention Notice of Dumisa Ntsebeza (a former commissioner, and investigation unit head, of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission), and Frank Dutton (an international policing and investigations expert who was instrumental in exposing the apartheid regime’s “Third Force”), powerful context is provided in relation to the modus operandi of the Security Branch of the 1980s. The organisation, their testimony shows, was mostly a criminal enterprise that used violent means to eliminate opponents—including non-combatants. Abduction, torture and murder were the order of the day. Those abducted who refused to work for the SB all met the same fate: death. This was done, according to Ntsebeza and Dutton, with the knowledge and oversight of the most senior police generals, the all-powerful State Security Council, and President PW Botha himself.

For example, in paragraph 20.7 of his affidavit, which was just one paragraph among dozens in a similar vein, Ntsebeza submitted this:

“The most senior SB offices routinely covered up crimes. See for example the finding of the TRC that SAP generals Johannes Van der Merwe and Basie Smit were responsible for defeating the ends of justice by helping to cover up the crimes of hit squad members (TRC Final Report, Vol 3 Ch. 3, Regional Profile: Natal and KwaZulu, p220).”

Frank Dutton, for his part, after detailing some of the findings from his work in the early 1990s as lead investigator in the Vlakplaas and KwaZulu-Natal hit squad cases, testified in paragraph 9 of his affidavit as follows:

“The knowledge that I derived from the above investigations and sources led me to conclude that the involvement of the SAP (and other Security Forces) in political violence was sanctioned not only by the most senior commanding officers in the SAP, including Commissioners of the SAP and commanders of the SB, but also by the highest levels of Government.”

Will such evidence, which is not exactly news to the vast majority of South Africans, appear in the prosecution’s case when the Simelane trial finally arrives at its real business? Probably not—if the NPA, like SAPS, are stuck on the “private frolic” angle. And definitely not—if they are aiming to avoid going up the chain of command.

Reflection V

Given that the accused admitted that the kopdraai (“turning by force”) of Nokuthula Simelane was authorised by Brigadier Hennie Muller, who is now deceased, and Brigadier Willem Schoon, who is still alive, why has the latter not been charged?

Awkwardly for the NPA, the indictment they delivered in January 2016 to the four accused had a lot in common, in terms of its statement of the facts, with a typical PW Botha-era Security Branch operation.

In 1983, the indictment noted, the four accused were attached to the Soweto Intelligence Unit of the Security Branch, where they were involved with intelligence gathering and controlling various classes of agents and informants. The unit by then had met with some success, and had managed to infiltrate Umkhonto we Sizwe in Swaziland. One day in September 1983, the unit received information that a meeting would take place at the Carlton Centre in Johannesburg between a deep cover agent and an MK operative by the name of Nokuthula Simelane. When Willem Coetzee, the unit’s commander (referred to in the indictment as “Accused 2”), told Brigadier Hennie Muller, the overall commander of the Soweto Security Police, about the meeting, it was agreed that the MK operative should be abducted and “turned”. Coetzee gathered his team (referred to in the indictment as “Accused 1-4”) and set to work.

These facts were further corroborated in an affidavit signed in 2016 by Coetzee, where he stated that he and his team were authorised by Brigadier Muller to “apprehend” Simelane and to “recruit her as an informer”. In a signed statement made under oath on 10 March 2016, Coetzee brought Brigadier Schoon—the commander of Section C of the Security Branch from 1981 to 1990—into the frame: he testified that he was instructed by Muller to accompany him to “head office” to meet Schoon, so as to secure “authorisation”. Which was the same information provided almost twenty years previously to the TRC, when Coetzee testified in an amnesty hearing that Schoon was briefed on the operation on the Saturday afternoon immediately following Simelane’s abduction.

Meaning? Meaning that Schoon, whose name did not appear in the indictment of January 2016, was off the hook once again.

As Ntsebeza testified in paragraph 34 of the abovementioned supporting affidavit, Schoon was implicated by the TRC in a large number of criminal incidents—so prominent was he, in fact, that he made multiple amnesty applications for crimes that ran the gamut from murder and kidnapping to bombings and perjury. Most of these applications were successful, but there was one that wasn’t. To wit, paragraph 34.4 of Ntsebeza’s affidavit:

“Brig Schoon and 4 others were refused amnesty for the murder of 2 persons and the attempted murder of 1 arising from a bombing in Krugersdorp in February 1982. The crimes were considered by the Amnesty Committee to be wholly disproportionate to the political objective pursued. Brig Schoon and his colleagues were not prosecuted for these crimes, notwithstanding the refusal of amnesty.”

Dutton expanded on the sentiment in his own supporting affidavit to the February 2017 intervention:

“It is noted that Brigadier Schoon applied for amnesty in respect of the Simelane matter, but did not proceed with his application. In my view, it is particularly remarkable and curious that Brigadier Schoon has escaped prosecution in this case, and other cases in which he did not apply for amnesty or was refused amnesty.”

*******

And so now, back at the MKMVA media briefing, the space-warp was happening on General Nyanda’s face—where, as per reports, the expression was one of total disbelief. On the placard that Sigovu had been waving in the air as he was escorted to the door, it stated: “Tell us about Nokuthula Simelane, Siphiwe Nyanda”. Whatever Sigovu was now saying outside the building, inside Nyanda was sweating. He had just been publicly tarred with the “apartheid mole” brush, and he was pretty sure it was a set-up.

Here was the problem. This briefing was a report-back about a meeting that had happened the week before, when the two factions that claimed to represent ordinary MK veterans—the MKMVA, as led by deputy minister of defence and military veterans Kebby Maphatsoe, and the MK national council, as led by Nyanda—agreed to work out their differences and unite. Why had they been fighting? Because Nyanda had moved publicly against President Jacob Zuma in a memorandum delivered to ANC secretary-general Gwede Mantashe in March 2016, and Maphatsoe had called Nyanda and his faction “empty tins”. In other words, why else?

“I know this comrade [Sigovu],” Nyanda later told a reporter from The Star. “He worked under my army machinery. I know he was arrested. He was supposed to have debriefed other comrades about his arrest, especially his quest to know about the whereabouts of Simelane. A lot has been written of how Simelane was captured.

“I had nothing to do with her. They might have worked together. As you know, there is a criminal prosecution under way of people accused of killing her. I did not expect this.”

Reflections within reflections. As the Daily Maverick reported in 2016, the four accused in the criminal matter of The State v MT Radebe and 3 Others have denied the charges and pled “not guilty”. Coetzee and Pretorius assert that they successfully “turned” Simelane into an apartheid agent after the first week of her detention, and that they then set themselves up as her handlers. Simelane, according to this version, was transported back to Swaziland to re-infiltrate MK structures, but she failed to keep her prearranged appointments with the handlers and was never heard from again. The assertion of the accused is that unknown members of MK in Swaziland, who felt they could no longer trust Simelane, committed the murder.

Could this have been true? Thembi Nkadimeng, in the founding affidavit attached to February 2017’s Intervention Notice, offered persuasive arguments for the fact that it wasn’t. Foremost among them was the TRC amnesty committee’s “flat rejection” of Coetzee’s claims, which neither Coetzee nor the other accused bothered to acknowledge. As per Nkadimeng, the amnesty committee found, on the basis of the evidence of a number of eye-witnesses, that:

a) Simelane “did not cooperate with the Security Branch and did not furnish any material information to them”;

b) “All attempts to recruit her as an informant proved ‘fruitless’”;

c) Simelane “sustained serious and prolonged torture to the point where she was hardly recognisable and could barely walk”; and

d) “Simelane was not returned to Swaziland following her captivity.”

So while Coetzee, Pretorius and Mong were granted amnesty by the TRC for the abduction of Simelane, they were denied amnesty for the torture on the grounds that their testimony was “untruthful” (the fourth accused, Timothy Msebenzi Radebe, did not apply for amnesty for the kidnapping and has thus been charged by the NPA with both kidnapping and murder).If Sigovu knew all of this—and he should have, given his obvious concern—there must’ve been another game he was playing at the media briefing in Luthuli House.

A game that had something to do with Kebby Maphatsoe’s calm smugness when Sigovu was accusing Nyanda of selling out Simelane? A game in which President Zuma’s background as head of ANC counter-intelligence was more than just a coincidence? A game where even the insinuation of “apartheid mole” was enough to shut down resistance?

A game at whose expense?

“Not only that,” it reads in the next line of the Buddhist sutra quoted above, “but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring.”

Forever? Forever ever? DM

Previously in Daily Maverick:

-

An apartheid murder reckoning (Part III): PW Botha’s ‘realm of criminality’, legal costs and Nokuthula Simelane. in Daily Maverick

- An apartheid murder reckoning: Does the NPA have the courage? In Daily Maverick

- An apartheid murder reckoning (part II): Jury still out on NPA’s courage; in Daily Maverick.

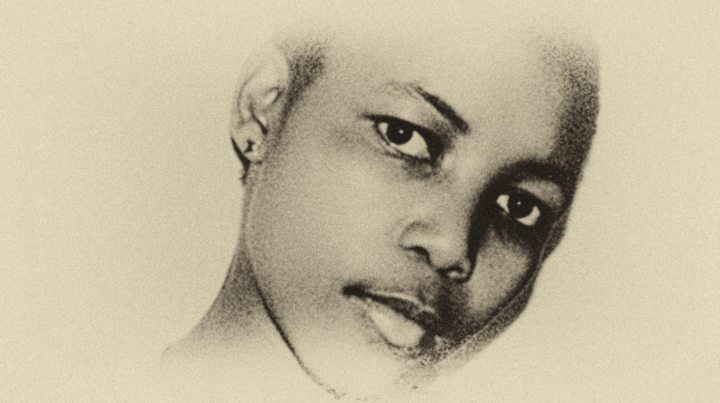

Photo: Nokuthula Simelane

Become an Insider

Become an Insider