PHOTOGRAPHY

Picturing Atrocity: The ethics of photographing violence

“A picture is worth 1,000 words.” So goes the age-old platitude: one can read about conflict and war, about a person being brutally tortured, or shot, or burnt, but no words (no matter how evocative) will have the same formidable impact as that of a photograph – a stilling of a terrible moment; a reflection of a horror that happened in real life. But what does it mean to photograph (and immortalise) violence? What does it mean to bear witness to it as an onlooker?

With the recent riots that started in KwaZulu-Natal, and the ongoing taxi wars in the Western Cape, our (social) media feeds are currently full of images of violence, conflict, and chaos. In 2019, Lindy Heinecken wrote in The Conversation about why South Africa might be a particularly violent nation, and how that might shape our (varied) experiences of living here; and on a more personal level, the effect that “doom-scrolling” (swiping/scrolling/clicking through endless news about tragedy, disaster, death) has on our mental health, and how to manage that.

But what of images of violence and death? Why do we record and immortalise such ugly realities? Why do we look at them, and how do we internalise them? What does it mean to capture violence?

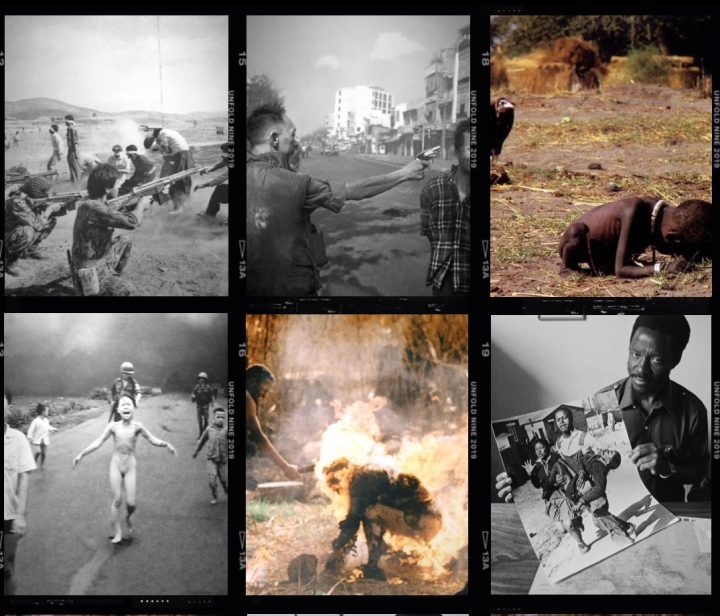

Justice and Cleansing in Iran; 1980 Pulitzer Prize, Spot News Photography, Jahangir Razmi of Ettela’at, Iran; On Aug. 27, in Sanandaj. The Pulitzer Prize was awarded to “an unnamed photographer,” which is how it stayed until 2006 when The Wall Siren Journal conclusively identified the photographer as Jahangir Razmi, who now runs a photo studio in Tehran. “There’s no more reason to hide.” Razmi told the Journal (Image: Flickr)

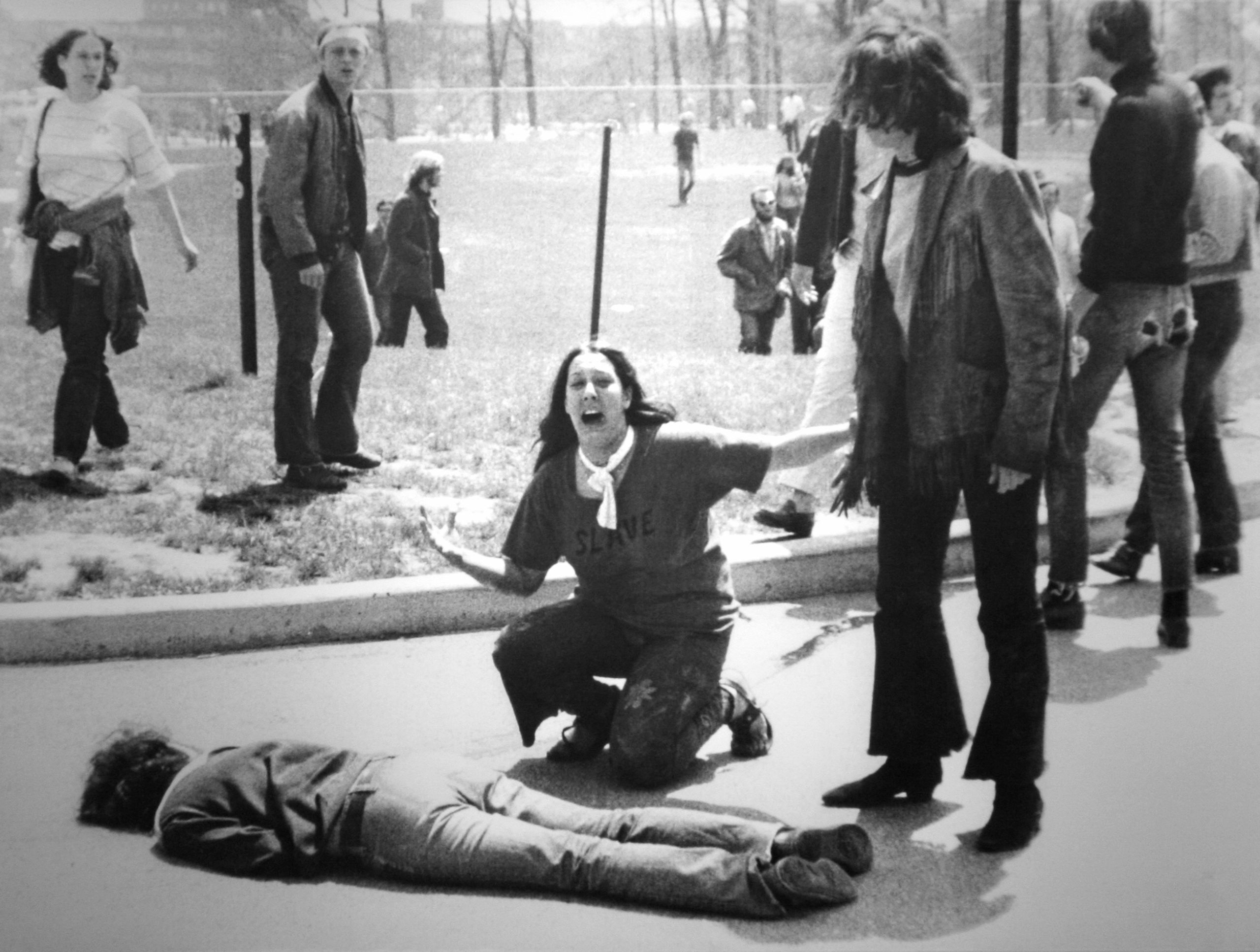

Kent State University Massacre; 1971 Pulitzer Prize, Spot News Photography, John Paul Filo, Valley Daily News and Daily Dispatch. (Image: Flickr)

Capturing the world around us

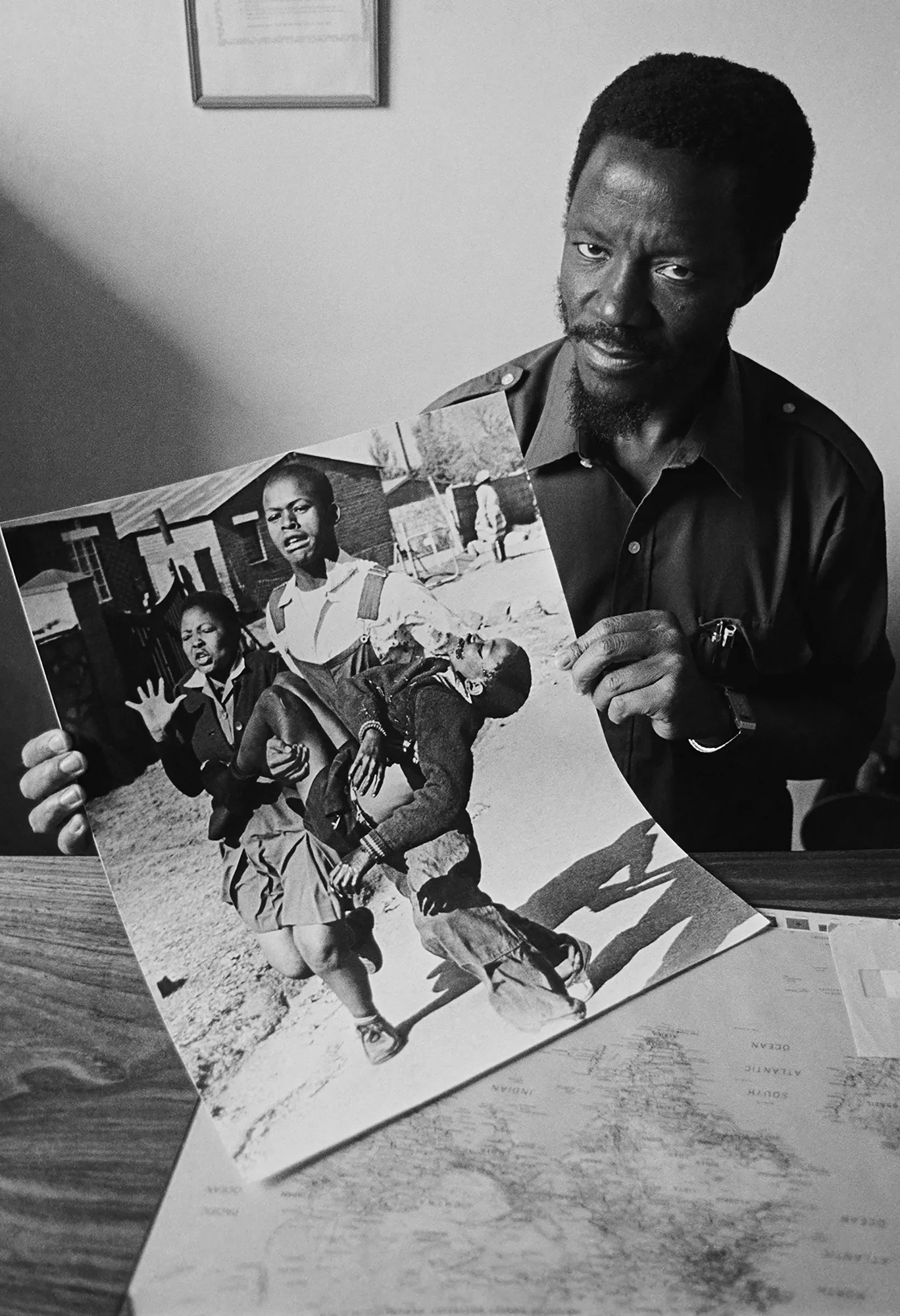

The impact that media coverage (specifically photographic coverage) of conflict can have is no breaking news. Think of the spine-chilling images of the Vietnam war which exposed countless human rights violations at the hands of American soldiers. Or, closer to home, Sam Nzima’s image of Hector Pieterson, shot during the 1976 Soweto Uprising, which became a rallying symbol for much anti-apartheid action and is now a tragic icon of apartheid violence.

Photographer Sam Nzima with his iconic image of Hector Peterson during the 1976 Soweto uprising. Photo:Paul Weinberg

The Terror of War: 1973 Pulitzer Prize, Spot News Photography, Huynh Cong “Nick” Út, Associated Press (Image: Flickr)

Saigon Execution; 1969 Pulitzer Prize, Spot News Photography, Edward Adams, Associated Press (Image: Flickr)

“I was ignoring it at first, the violence. I thought, this is not for me,” explains Greg Marinovich, award-winning photojournalist, filmmaker and co-author of The Bang-Bang Club (among other publications, and the man who broke the real Marikana Massacre story for Daily Maverick). The Bang-Bang Club book is a non-fiction account of the work of four legendary conflict photographers (Ken Oosterbroek, Kevin Carter, Joao Silva, and Marinovich himself) that centred on the hostel wars of the early 90s. Marinovich continues: “But then I thought, no, if I’m going to cover what apartheid is, I’ve got to do this.”

That some of Marinovich’s photographs depict horrendous acts of violence is no question. His Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, perhaps one of the goriest, titled “Human Torch”, shows a Zulu man (Lindsaye Tshabalala), burning to death, his body set alight by ANC supporters. Others display similarly devastating and hard-to-look-at scenes.

Human Torch; 1991 Pulitzer Prize, Spot News Photography, Greg Marinovich, Associated Press; Soweto. South Africa (Image: Flickr)

Author/photographer Greg Marinovich speaks at the panel on April 23, 2011 in New York City. (Photo by Slaven Vlasic/Getty Images)

Marinovich’s images, as well as those taken by the other members of the Bang-Bang Club, were created in an effort to expose the truth about the violence in South Africa. Their work was a rallying cry and a call to protest for both South Africans and the rest of the world. These images said: “Stop! Look at the devastation that is going on here.”

“To not picture atrocity is therefore to omit what’s there, to fail the truth of a situation, to withhold that proof.”

In the preface to The Bang-Bang Club, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu wrote about the photographers: “We owe them a tremendous debt for their contribution to the fragile process of transition from repression to democracy, from injustice to freedom.”

On why such images make us pay attention, Susie Linfield, author of The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence, writes that photographs of violence “show how easily we are reduced to the mere physical, which is to say how easily the body can be maimed, starved, splintered, beaten, burnt, torn, and crushed”.

In reminding us of the frailty of our human physicality, of our soft and vulnerable bodies, of the shame and pain that each of us is capable of feeling, these photographs ask us: “What have we done to create the conditions in which others, our fellow citizens, undergo such unspeakable experiences.” At best, photographs of violence are an effective way of inciting empathy and, more so, action.

But perhaps most importantly, photographic evidence of atrocities can provide proof that such tragedies happened at all. As Jay Prosser puts it in the introduction to a collaborative essay book, Picturing Atrocity, “to not picture atrocity is therefore to omit what’s there, to fail the truth of a situation, to withhold that proof. Equally, to not look at pictures of atrocity is to deny its existence, not only when atrocity happens at a distance but also when it’s there on our doorsteps, in front of us.”

Marinovich agrees: “Some people might say, you have to photograph it discreetly, so that you don’t show the violence. I think, why? If that’s what is happening, then who am I, who are you, to censor it?”

Arguably, attempting to silence evidence of atrocity is the worst violence of all. Looking at images of violence is difficult; it hurts and it shames us; it shows the human body in a moment of vulnerability that is terrifying and almost repulsive… But the real crime is that these acts are happening in the first place. Ignoring or destroying evidence of them is just one more act of destruction.

As Prosser writes: “Atrocity is going on all around us. The least we can do is acknowledge it.”

As with everything in life, there is, of course, a darker side to picturing atrocity.

In another part of the preface to The Bang-Bang Club, Tutu writes about the group of photographers: “They must have been endowed with extraordinary courage to work in death zones with so much nonchalance and professionalism. And they must have been remarkably cool, no, even cold-blooded, to look on it all as being part of a day’s work.”

Tutu is poking at a central conflict in the ethics of photographing moments of violence: where does the line between being a professional journalist and an empathetic human being lie? At what point do you put down your camera to help where you can? When is it ethical to interfere, and when is an interference going to hinder the truth of an image that might have served a larger cause?

“There is a price extracted with every such frame: some of the emotion, the vulnerability, the empathy that makes us human, is lost every time the shutter is released.”

These questions are impossible to avoid. A perfect illustration of this conundrum might be the story of Kevin Carter, also a member of the Bang-Bang club. His Pulitzer-winning photograph, “Starving Child and Vulture”, taken in 1993 in Sudan during a famine that wracked the land, shows a skeletal (but living) toddler curled in on herself in a moment of exhaustion. Head too big for a body sharp with poking bones, the toddler is desperately trying to make her way across a dry field, alone… Aside from a single vulture, that watches menacingly in the background.

Kevin Carter’s “Starving Child and Vulture”, taken in 1993 in Sudan during a famine that wracked the land. (Image Flickr)

Carter’s photograph was achingly poignant and moving. But soon, people began asking why Carter wouldn’t have tried, instead of taking a picture, to save the child. His very humanity was questioned. It later turned out that the child in the photograph survived, eventually making it to a feeding station nearby, and that the father was standing just metres away.

Carter, however, did not survive. He took his own life a year later, his image becoming an agonising case study in the debate as to when journalists should – or should not – intervene. Art historian and cultural analyst Griselda Pollock asks: “Can photography kill its agent?”

Marinovich writes in The Bang-Bang Club: “Tragedy and violence certainly make powerful images. It’s what we get paid for. But there is a price extracted with every such frame: some of the emotion, the vulnerability, the empathy that makes us human, is lost every time the shutter is released.”

But the ethical implications of violent imagery do not stop with the photographer. What of the people who look at the image, who might gaze at a starving little girl for a few minutes without knowing her name or her story, flip the page or click away, and promptly forget that she even existed.

Prosser writes: “The conventions of atrocity photographs can require or even rely on showing people in a world apart from where we look at these photographs, suffering people whose condition is often emblematised in their states of undress, or nakedness or other forms of bodily vulnerability. The state of the body in the photograph and the state of the body viewing the photograph often could not be more different.”

He continues: “The imbalance is geopolitical: showing atrocity abroad tends to be acceptable; there’s more circumspection in what is shown of atrocities closer to home.”

Indeed, it may be seemingly easier to look at an image of a strange, faraway, unnamed toddler starving to death as a vulture looks on, than a picture of, say, someone closer to us – even culturally – in a similar predicament.

“The repetition of the visual, discursive state, and other quotidian and extraordinary cruel and unusual violences enacted on Black people does not lead to a cessation of violence, nor does it, across or within communities, lead primarily to sympathy or something like empathy. Such repetitions often work to solidify and make continuous the colonial project of violence.”

Images of atrocity are also undeniably racially weighted. Marinovich brings up the point that US photographers and publications published very few images of American people suffering and dying from Covid-19. “But then you see Indian people dying in the most graphic way.”

In The Bang-Bang Club there is a striking image of several dead Afrikaners, members of the AWB (an extreme right-wing, white supremacist organisation in South Africa) executed by Bophuthatswana police. Their lumpy white bodies are shown in compromising positions; one man’s thick thighs hang from a car in an unattractive and embarrassing manner, another man’s head slumps unnaturally to the side, eyes wide open but obviously dead. This is far from the most gruesome photo in the book, yet it curiously catches the eye and sticks in the memory. The reason: the dead people pictured are white. Skewed geopolitics and its reflection in the media make it such that we are much more accustomed to seeing black and brown bodies in images of atrocity. There are thousands of pictures of starving children in Africa.

“As a journalist, you are not meant to be neutral. You’re meant to be honest. To represent honestly what you see and what you understand.”

Professor of English literature and black studies at York University, Toronto, Christina Sharpe writes in her book In the Wake: “The repetition of the visual, discursive state, and other quotidian and extraordinary cruel and unusual violences enacted on Black people does not lead to a cessation of violence, nor does it, across or within communities, lead primarily to sympathy or something like empathy. Such repetitions often work to solidify and make continuous the colonial project of violence.” If we see continuous images of black and brown bodies being violently treated, it becomes a normalised sight, no longer shocking or galvanising.

If you have seen the film Nightcrawler – in which Jake Gyllenhaal plays a creepy and obsessively ambitious amateur disaster journalist who makes a living solely from footage of car crashes and murders – you have seen the nightmare of a mercenary conflict photographer taken to its logical extreme. For Gyllenhaal’s character there is no larger, honourable mission that drives his work, there is only money and a twisted kind of fame.

This, while dramatised, is not that far from reality. As Marinovich writes in The Bang-Bang Club: “I was swiftly learning the dictum of journalism: if it bleeds, it leads.”

Context and responsibility

How do we reconcile the absolute necessity of documenting atrocity, of showing that atrocious things have happened (and still happen) to real people, with its ugliness and potential exploitation?

According to Marinovich, context is absolutely key. As is taking responsibility.

“You have to give the context because a photograph is one angle, one tiny fraction of a second, out of a huge geographic space. There are 24 hours in a day. Which angle do you use? What lens do you use? Which moment in the day?”

If a photograph has the appropriate amount of context to accompany it, then it is no longer just another picture of a starving child in Africa, or a wounded soldier. It’s a story about a human being. It’s also much less likely to be twisted and used in ways that change the meaning of the image.

According to Marinovich, there is no such thing as being an objective photographer. As a journalist, he thinks, “you are not meant to be neutral. You’re meant to be honest. To represent honestly what you see and what you understand.”

He continues: “What is objective? Yes, it sounds good, but it’s not possible. We all have our baggage. You’re female, I’m male. You have blonde hair; I have no hair. We’re both white, we’re both South African. So, we come from a certain subjective point of view. We are, objectively, in different places.”

The acknowledgement of this “baggage” is essential, because different individuals will have differing perspectives, whether this stems from opinions or more practical access.

For example, Marinovich explained, one of the reasons he was able to get some of his most famous images during the hostel wars was because he was white. His skin colour meant he was less harassed by police and seen as a neutral observer by both the ANC and IFP supporters. A photographer of colour would never have had access to the same spaces.

“Once we acknowledge subjectivity as to how we approach something, even how we choose our subjects, what we’re going to cover, who we’re going to interview, etc, I think we’re a big step closer to offering our potential audience an honest representation, a chance for them to filter our biases, our own filters. Or to acknowledge and understand where we are coming from. That is key. This blunt pretending to be objective, it obfuscates things. It’s actually an impediment to honesty.”

To have ethically sound and impactful images of violence, it is the journalist’s responsibility to give as honest a depiction of events as possible. “The key is to photograph in a way that is unambiguous, doesn’t misrepresent a situation, yet even though the photograph is just capturing an instant, to try and capture something that represents the truth of what was happening in that moment. The greater truth of that half hour, that hour, that day.”

“It’s up to us to begin to investigate these histories, and to learn what it is these photographs are saying.”

But there are several levels of responsibility. Editors, too, must publish as accurate and full a story of the violence as possible. There are countless examples of publications using images out of context and totally skewing the meaning of a photograph. Marinovich talks about how many of his photographs that depicted violence between members of the ANC and the IFP were published adjacent to stories that used “bullshit police-statements”, which completely compromised the honesty of the image.

“Sometimes you’ve got to shoot for posterity and understand that occasionally your work is going to get abused along the way. And it does. There is nothing you can do about that.”

The responsibility that lies with us, the viewers, the consumers of violent imagery, is to educate ourselves about all of these things. To know that images can be twisted, and to responsibly check ourselves and our facts.

As Linfield told The New Yorker in this interview: “I make a plea, in my book, for viewers to become more proactive – instead of endlessly whining about all the things that photographs can’t do and don’t tell us, and all the ways that they are too superficial, etc. Some of that may be true. But it’s up to us to begin to investigate these histories, and to learn what it is these photographs are saying.”

As Nigerian-American writer and photographer Teju Cole put it: “Photography works and doesn’t work, it is tolerable and intolerable, it confounds and often exceeds our expectations.”

What’s more, the story is made even more complex with the digital revolution; everyone and anyone with a cellphone can be a conflict photographer. Now what do we make of that? DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Very nice article, thank you. These are issues that every photographer should engage with, even if not a photojournalist. The wider context and honesty should always be part of the process of how we photograph and represent the world we live in. This should also apply to everyone with a cellphone that decides to record an event, but if this honesty and context is already lacking in so many so called professional photographers how can we expect these considerations to be taken into account by someone who has never engaged with photography as a profession and that just happens to be a witness with the means to register the event? Add to this the ability we all have to disseminate an image wide and far through social media and we have all these decontextualized images floating around that are being used in fake news and to boost dishonest agendas. I don’t have easy answers but I do think we all need to consider the power we hold in these devices we carry around everywhere, we must apply good judgment when we press record, when we click and when we share images. We need to resist the knee jerk reaction to use these devices as a way to deal with our own anxiety and behave like irresponsible citizens. These devices also give us the comfort of registering events at a distance, without trying to understand the situation which leaves it open to misunderstandings and bias. It has also made work difficult for photojournalism which is not the only source of image making anymore.